Maya codices

Maya codices (singular codex) are folding books written by the pre-Columbian Maya civilization in Maya hieroglyphic script on Mesoamerican bark paper. The folding books are the products of professional scribes working under the patronage of deities such as the Tonsured Maize God and the Howler Monkey Gods. The codices have been named for the cities where they eventually settled. The Dresden codex is generally considered the most important of the few that survive.

The Maya made paper from the inner bark of a certain wild fig tree, Ficus cotinifolia.[1][2] This sort of paper was generally known by the word huun in Mayan languages (the Aztec people far to the north used the word āmatl [ˈaːmat͡ɬ] for paper). The Maya developed their huun-paper around the 5th century.[3] Maya paper was more durable and a better writing surface than papyrus.[4]

Our knowledge of ancient Maya thought must represent only a tiny fraction of the whole picture, for of the thousands of books in which the full extent of their learning and ritual was recorded, only four have survived to modern times (as though all that posterity knew of ourselves were to be based upon three prayer books and Pilgrim's Progress).

— Michael D. Coe[5]

Background

There were many books in existence at the time of the Spanish conquest of Yucatán in the 16th century; most were destroyed by the Catholic priests.[6] Many in Yucatán were ordered destroyed by Diego de Landa in July 1562.[7] Bishop de Landa hosted a mass book burning in the city of Mani in the Yucatán peninsula.[8] De Landa wrote:

We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which were not to be seen as superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction.

Such codices were the primary written records of Maya civilization, together with the many inscriptions on stone monuments and stelae that survived. Their range of subject matter in all likelihood embraced more topics than those recorded in stone and buildings, and was more like what is found on painted ceramics (the so-called 'ceramic codex'). Alonso de Zorita wrote that in 1540 he saw numerous such books in the Guatemalan highlands that "recorded their history for more than eight hundred years back, and that were interpreted for me by very ancient Indians".[9]

Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas lamented when he found out that such books were destroyed: "These books were seen by our clergy, and even I saw part of those that were burned by the monks, apparently because they thought [they] might harm the Indians in matters concerning religion, since at that time they were at the beginning of their conversion." The last codices destroyed were those of Nojpetén, Guatemala in 1697, the last city conquered in the Americas.[10] With their destruction, access to the history of the Maya and opportunity for insight into some key areas of Maya life was greatly diminished.

Three fully Mayan codices have been preserved. These are:

- The Dresden Codex also known as the Codex Dresdensis (74 pages, 3.56 metres [11.7 feet]);[11] dating to the 11th or 12th century.[12]

- The Madrid Codex, also known as the Tro-Cortesianus Codex (112 pages, 6.82 metres [22.4 feet]) dating to the Postclassic period of Mesoamerican chronology (circa 900–1521 AD).;

- The Paris Codex, also known as the Peresianus Codex (22 pages, 1.45 metres [4.8 feet]) tentatively dated to around 1450, in the Late Postclassic period (AD 1200–1525)

A fourth codex, lacking hieroglyphs, is Maya-Toltec rather than Maya. It remained controversial until 2015, when extensive research finally authenticated it:

- The Grolier Codex, also known as the Sáenz Codex (10 pages) or Códice Maya de México.[14][15][16]

Dresden Codex

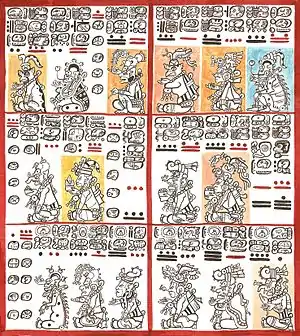

The Dresden Codex (Codex Dresdensis) is held in the Sächsische Landesbibliothek (SLUB), the state library in Dresden, Germany. It is the most elaborate of the codices, and also a highly important specimen of Maya art. Many sections are ritualistic (including so-called 'almanacs'), others are of an astrological nature (eclipses, the Venus cycles). The codex is written on a long sheet of paper that is 'screen-folded' to make a book of 39 leaves, written on both sides. It was probably written between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries.[17] After it was taken to Europe and was bought by the royal library of the court of Saxony in Dresden in 1739. The only exact replica, including the huun, made by a German artist is displayed at the Museo Nacional de Arqueología in Guatemala City, since October 2007.

It is not clear who brought the Dresden Codex to Europe.[18] It arrived sometime in the late 18th century, potentially from the first or second generation of Spanish conquistadores. Even though the last date entry in the book is from several centuries before its relocation, the book was likely used and added to until just before the conquerors took it.

About 65 per cent of the pages in the Dresden Codex contain richly illustrated astronomical tables. These tables focus on eclipses, equinoxes and solstices, the sidereal cycle of Mars, and the synodic cycles of Mars and Venus. These observations allowed the Mayans to plan the calendar year, agriculture, and religious ceremonies around the stars. In the text, Mars is represented by a long nosed deer, and Venus is represented by a star.

Pages 51–58 are eclipse tables. These tables accurately predicted solar eclipses for 33 years in the 8th century, though the predictions of lunar eclipses were far less successful. Icons of serpents devouring the sun symbolize eclipses throughout the book. The glyphs show roughly 40 times in the text, making eclipses a major focus of the Dresden Codex.

The first 52 pages of the Dresden Codex are about divination. The Mayan astronomers would use the codex for day keeping, but also determining the cause of sickness and other misfortunes.

Though a wide variety of gods and goddesses appear in the Dresden Codex, the Moon Goddess is the only neutral figure.[19] In the first 23 pages of the book, she is mentioned far more than any other god.

Between 1880 and 1900, Dresden librarian Ernst Förstemann succeeded in deciphering the Maya numerals and the Maya calendar and realized that the codex is an ephemeris.[20] Subsequent studies have decoded these astronomical almanacs, which include records of the cycles of the Sun and Moon, including eclipse tables, and all of the naked-eye planets.[21] The "Serpent Series", pp. 61–69, is an ephemeris of these phenomena that uses a base date of 1.18.1.8.0.16 in the prior era (5,482,096 days).[22][23]

Madrid Codex

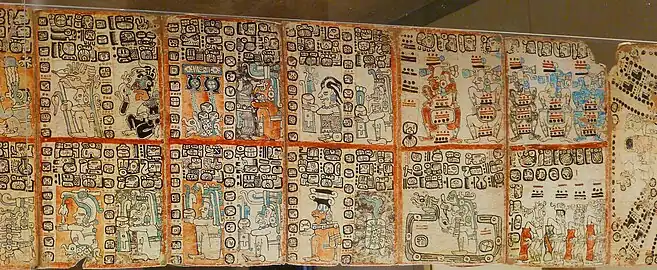

The Madrid Codex was rediscovered in Spain in the 1860s; it was divided into two parts of differing sizes that were found in different locations. The Codex receives its alternate name of the Tro-Cortesianus Codex after the two parts that were separately discovered.[25] Ownership of the Troano Codex passed to the Museo Arqueológico Nacional ("National Archaeological Museum") in 1888.[26] The Museo Arqueológico Nacional acquired the Cortesianus Codex from a book-collector in 1872, who claimed to have recently purchased the codex in Extremadura.[27] Extremadura is the province from which Francisco de Montejo and many of his conquistadors came, as did Hernán Cortés, the conqueror of Mexico.[28] It is therefore possible that one of these conquistadors brought the codex back to Spain; the director of the Museo Arqueológico Nacional named the Cortesianus Codex after Hernán Cortés, supposing that he himself had brought the codex back.[28]

The Madrid Codex is the longest of the surviving Maya codices.[26] The content of the Madrid Codex mainly consists of almanacs and horoscopes that were used to help Maya priests in the performance of their ceremonies and divinatory rituals. The codex also contains astronomical tables, although fewer than the other two generally accepted surviving Maya codices. A close analysis of glyphic elements suggests that a number of scribes were involved in its production, perhaps as many as eight or nine, who produced consecutive sections of the manuscript; the scribes were likely to have been members of the priesthood.[29]

Some scholars, such as Michael Coe and Justin Kerr,[30] have suggested that the Madrid Codex dates to after the Spanish conquest but the evidence overwhelmingly favours a pre-conquest date for the document. It is likely that the codex was produced in Yucatán. J. Eric Thompson was of the opinion that the Madrid Codex came from western Yucatán and dated to between 1250 and 1450 AD. Other scholars have expressed a differing opinion, noting that the codex is similar in style to murals found at Chichen Itza, Mayapan and sites on the east coast such as Santa Rita, Tancah and Tulum. Two paper fragments incorporated into the front and last pages of the codex contain Spanish writing, which led Thompson to suggest that a Spanish priest acquired the document at Tayasal in Petén.[32]

Paris Codex

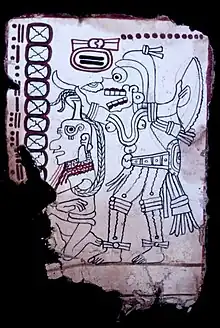

The Paris Codex (also or formerly the Codex Peresianus) contains prophecies for tuns and katuns (see Maya Calendar), as well as a Maya zodiac, and is thus, in both respects, akin to the Books of Chilam Balam. The codex first appeared in 1832 as an acquisition of France's Bibliothèque Impériale (later the Bibliothèque Nationale, or National Library) in Paris. Three years later the first reproduction drawing of it was prepared for Lord Kingsborough, by his Lombardian artist Agostino Aglio. The original drawing is now lost, but a copy survives among some of Kingsborough's unpublished proof sheets, held in collection at the Newberry Library, Chicago.[33]

Although occasionally referred to over the next quarter-century, its permanent rediscovery is attributed to the French orientalist Léon de Rosny, who in 1859 recovered the codex from a basket of old papers sequestered in a chimney corner at the Bibliothèque Nationale where it had lain discarded and apparently forgotten.[34] As a result, it is in very poor condition. It was found wrapped in a paper with the word Pérez written on it, possibly a reference to the Jose Pérez who had published two brief descriptions of the then-anonymous codex in 1859.[35] De Rosny initially gave it the name Codex Peresianus ("Codex Pérez") after its identifying wrapper, but in due course the codex would be more generally known as the Paris Codex.[35] De Rosny published a facsimile edition of the codex in 1864.[36] It remains in the possession of the Bibliothèque Nationale.

Maya Codex of Mexico

Formerly named the Grolier Codex, but renamed in 2018, the Maya Codex of Mexico was discovered in 1965.[37] The codex is fragmented, consisting of eleven pages out of what is presumed to be a twenty-page book and five single pages.[38] The codex has been housed at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, Mexico, since 2016, and is the only of the four Maya codices that still resides in the Americas.[39] Each page shows a hero or god, facing to the left. At the top of each page is a number, and down the left of each page is what appears to be a list of dates. The pages are much less detailed than in the other codices, and hardly provide any information that is not already in the Dresden Codex. Although its authenticity was initially disputed, various tests conducted in the early 21st century supported its authenticity and Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History judged it to be an authentic Pre-Columbian codex in 2018.[16][40] It has been dated to between 1021 and 1154 CE.[41]

Other Maya codices

Given the rarity and importance of these books, rumors of finding new ones often develop interest. Archaeological excavations of Maya sites have turned up a number of rectangular lumps of plaster and paint flakes, most commonly in elite tombs. These lumps are the remains of codices where all the organic material has rotted away. A few of the more coherent of these lumps have been preserved, with the slim hope that some technique to be developed by future generations of archaeologists may be able to recover some information from these remains of ancient pages. The oldest Maya codices known have been found by archaeologists as mortuary offerings with burials in excavations in Uaxactun, Guaytán in San Agustín Acasaguastlán, and Nebaj in El Quiché, Guatemala, at Altun Ha in Belize and at Copán in Honduras. The six examples of Maya books discovered in excavations date to the Early Classic (Uaxactún and Altun Ha), Late Classic (Nebaj, Copán), and Early Postclassic (Guaytán) periods. Unfortunately, all of them have degraded into unopenable masses or collections of very small flakes and bits of the original texts. Thus it may never be possible to read them.[42]

Forgeries

Since the start of the 20th century, forgeries of varying quality have been produced. Two elaborate early 20th-century forged codices were in the collection of William Randolph Hearst.

Notes

- Schottmueller, Paul Werner (February 2020). A Study of the Religious Worldview and Ceremonial Life of the Inhabitants of Palenque and Yaxchilan (MLA). Harvard University. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- Hellmuth, Nicholas M. "Economic Potential for Amate Trees" (PDF). Maya Archaeology. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- Burns, Marna (2004). The Complete Book of Handcrafted Paper. Dover Publications. p. 199. ISBN 9780486435442.

- Wiedemann, Hans G.; Brzezinka, Klaus-Werner; Witke, Klaus & Lamprecht, Ingolf (May 2007). "Thermal and Raman-spectroscopic analysis of Maya Blue carrying artefacts, especially fragment IV of the Codex Huamantla". Thermochimica Acta. 456 (1): 56–63. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2007.02.002.

- Coe, Michael D. The Maya, London: Thames and Hudson, 4th ed., 1987, p. 161

- Foster, Lynn V. (2002). Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World. New York: Facts On File. p. 297. ISBN 978-0816041480.

- Diego de Landa) William Gates, translator, (1937) 1978. Yucatan Before and After the Conquest. An English translation of Landa's Relación Retrieved 22 Mar 2017

- Bower, Jessica (1 September 2016). "The Mayan Written Word: History, Controversy, and Library Connections". The International Journal of the Book. 14 (3): 15–25. doi:10.18848/1447-9516/CGP/v14i03/15-25. ProQuest 2714043792. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- Zorita 1963, 271–272

- Maya writing Archived 2007-06-13 at the Wayback Machine

- "O Códice de Dresden". World Digital Library. 1200–1250. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- Murray, Stuart (2009). Library, the : an illustrated history. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. p. 140. ISBN 9781628733228.

- Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (30 August 2018). "Boletín 299: INAH ratifica al Códice Maya de México, antes llamado Grolier, como el manuscrito auténtico más antiguo de América" (PDF). gob.mx. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- "13th century Maya codex, long shrouded in controversy, proves genuine". News from Brown. Brown University. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- Blakemore, Erin (15 September 2016). "New Analysis Shows Disputed Maya "Grolier Codex" Is the Real Deal". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- Ruggles, Clive L. N. (2005). Ancient Astronomy: An Encyclopedia of Cosmologies and Myth. ABC-CLIO. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-85109-477-6.

- Vail, Gabrielle (2015). "Astronomy in the Dresden Codex". Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy. pp. 695–708. Bibcode:2015hae..book..695V. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6141-8_65. ISBN 978-1-4614-6140-1.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Barnhart, Edwin (Fall 2005). "The First Twenty-Three Pages of the Dresden Codex: The Divination Pages" (PDF): 1–145.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Ernst Förstemann, Commentary on the Maya Manuscript in the Royal Public Library of Dresden, Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University Vol. IV, No. 2, Cambridge Mass. 1902

- John Eric Sidney Thompson, A commentary on the Dresden Codex: A Maya Hieroglyphic Book, Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society, 1972.

- Beyer, Hermann 1933 Emendations of the 'Serpent Numbers' of the Dresden Maya Codex. Anthropos (St. Gabriel Mödling bei Wien) 28: pp. 1–7. 1943 The Long Count Position of the Serpent Number Dates. Proc. 27th Int. Cong. Of Amer., Mexico, 1939 (Mexico) I: pp. 401–405.

- Grofe, Michael John 2007 The Serpent Series: Precession in the Maya Dresden Codex

- FAMSI.

- Noguez et al. 2009, p. 20.

- Noguez et al. 2009, pp. 20–21.

- Noguez et al. 2009, p. 21.

- Ciudad et al. 1999, pp. 877, 879.

- Miller 1999, p. 187.

- Coe 1999, p. 200. Ciudad et al. 1999, p. 880.

- See "The Paris Codex", in Marhenke (2003), .

- Coe (1992, p. 101), Sharer & Traxler (2006, p. 127)

- Stuart (1992, p. 20)

- Coe (1992, p. 101)

- "FAMSI - Maya Codices - The Grolier Codex". www.famsi.org. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- "Grolier Codex | Mayan literature". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2016-05-09. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- Blakemore, Erin (2016-09-15). "New Analysis Shows Disputed Maya "Grolier Codex" Is the Real Deal". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- Boletín N° 299 (2018). "INAH ratifica al Códice Maya de México, antes llamado Grolier, como el manuscrito auténtico más antiguo de América" (PDF) (Press release) (in Spanish). Mexico: INAH. Retrieved 2018-09-22.

- Bonello, Deborah (31 August 2018). "Mexican historians prove authenticity of looted ancient Mayan text". The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Whiting 1998: 207–208

References

- Baudez, Claude (2002). "Venus y el Códice Grolier". Arqueología Mexicana. 10 (55): 70–79, 98–102.

- Ciudad Ruiz, Andrés; Alfonso Lacadena (1999). J.P. Laporte and H.L. Escobedo (ed.). "El Códice Tro-Cortesiano de Madrid en el contexto de la tradición escrita Maya" [The Tro-Cortesianus Codex of Madrid in the context of the Maya writing tradition] (PDF). Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1998 (in Spanish). Guatemala City, Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología: 876–888. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-14. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- Coe, Michael D. (1992). Breaking the Maya Code. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05061-3. OCLC 26605966.

- Coe, Michael D. (1999). The Maya. Ancient peoples and places series (6th, fully revised and expanded ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28066-9. OCLC 59432778.

- FAMSI. "Maya Hieroglyphic Writing – The Ancient Maya Codices: The Madrid Codex". FAMSI (Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies). Retrieved 2012-07-24.

- Kelker, Nancy L.; Karen O. Bruhns (2010). Faking Ancient Mesoamerica. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press. ISBN 978-1-59874-150-6.

- Marhenke, Randa (2003). "The Ancient Maya Codices". Maya Hieroglyphic Writing. Mesoweb. OCLC 53231537. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- Milbrath, Susan (2002). "New Questions Concerning the Authenticity of the Grolier Codex". Latin American Indian Literatures Journal. 18 (1): 50–83.

- Miller, Mary Ellen (1999). Maya Art and Architecture. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20327-9. OCLC 41659173.

- Noguez, Xavier; Manuel Hermann Lejarazu; Merideth Paxton; Henrique Vela (August 2009). "Códices Mayas" [Maya codices]. Arqueología Mexicana: Códices Prehispánicos y Coloniales Tempranos – Catálogo (in Spanish). Editorial Raíces. Special Edition (31): 10–23.

- Sharer, Robert J.; Loa P. Traxler (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th (fully revised) ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4816-2. OCLC 28067148.

- Stuart, George E. (1992). "Quest for Decipherment:A Historical and Biographical Survey of Maya Hieroglyphic Decipherment". In Elin C. Danien; Robert J. Sharer (eds.). New Theories on the Ancient Maya. University Museum Monograph series, no. 77. Philadelphia: University Museum, University of Pennsylvania. pp. 1–64. ISBN 978-0-924171-13-0. OCLC 25510312.

- Thompson, J.E.S. (1975). "The Codex Grolier". Contributions of the University of California. 27 (1): 1–9.

- Thompson, J.E.S. (1976). "The Grolier Codex". The Book Collector. 25 (1): 64–75.

- Whiting, Thomas A. L. (1998). "The Maya Codices". In Peter Schmidt; Mercedes de la Garza; Enrique Nalda (eds.). Maya. New York City: Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0847821297.

External links

- The Construction of the Codex In Classic- and Postclassic-Period Maya Civilization Archived 2002-10-17 at the Wayback Machine Maya Codex and Paper Making

- Maya Codices

- Complete Dresden codex as JPG,

- Complete Dresden codex as PDF

- Complete Madrid Codex as PDF

- Complete Paris Codex as PDF (Moderate size PDF)

- Complete Grolier Codex as JPG

- Codex and Maya Writing

- The Maya Codex and the Maya Astronomy

- Dresden Codex and the Mayan Calendar Archived 2006-02-12 at the Wayback Machine

- The Dresden Codex Lunar Series and Sidereal Astronomy