Medeshamstede

Medeshamstede /miːdsˈhæmstɛd/ was the name of Peterborough in the Anglo-Saxon period.[1] It was the site of a monastery founded around the middle of the 7th century, which was an important feature in the kingdom of Mercia from the outset. Little is known of its founder and first abbot, Sexwulf, though he was himself an important figure, and later became bishop of Mercia. Medeshamstede soon acquired a string of daughter churches, and was a centre for an Anglo-Saxon sculptural style.

Nothing is known of Medeshamstede's history from the later 9th century, when it is reported in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of 864 to have been destroyed by Vikings and the Abbot and Monks murdered by them, until the later 10th century, when it was restored as a Benedictine abbey by Bishop Æthelwold of Winchester, during a period of monastic reform. Through aspects of this restoration, Medeshamstede soon came to be known as "Peterborough Abbey".[2]

The name "Medeshamstede"

The name has been interpreted by a place-name authority as "homestead belonging to Mede".[4]

An alternative description is 'Medu' meaning Mead then 'Hamme' a village on a river and 'Steð'(the ð is pronounced th) meaning a bank or sea shore(the sea was about 4.5 metres higher in early saxon times), so the 'Mead village in the valley with a landing stage' [5]

According to the Peterborough version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written in the 12th century, this name was given at the time of the foundation of a monastery there in the 7th century, owing to the presence of a spring called "Medeswæl", meaning "Medes-well". However the name is commonly held to mean "homestead in the meadows", or similar, on an assumption that "Medes-" means "meadows".[6][7]

The earliest reliable occurrence of the name is in Bede's Ecclesiastical History, where it is mentioned in the genitive Latinised form "Medeshamstedi", in a context dateable prior to the mid-670s.[8] However the area had long been inhabited, for example at Flag Fen, a Bronze Age settlement a little to the east, and at the Roman town of Durobrivae, on the other side of the River Nene, and some five miles to the west. It is possible that "Medeshamstede" began as the name of an unrecorded, pre-existing Anglian settlement, at or near the site.

Another early form of this name is "Medyhæmstede", in an 8th-century Anglo-Saxon royal charter preserved at Rochester Cathedral.[9] Also found is "Medelhamstede", in the late 10th century Ælfric of Eynsham’s account of the life of St Æthelwold of Winchester, and on a contemporary coin of King Æthelred II, where it is abbreviated to "MEĐEL" /ˈmiːðəl/.[10] A much later development is the form "Medeshampstede", and similar variants, which presumably arose alongside similar changes, e.g. from Old English "[North] Hamtun" to the modern "Northampton". Despite the fact that they are therefore strictly unhistorical, forms such as "Medeshampstede" are found in later, historical writings.[11]

Locally, Anglo-Saxon records use "Medeshamstede" up to about the reign of King Æthelred II, but modern historians generally use it only to the reign of his father King Edgar, and use "Peterborough Abbey" for the monastery thereafter, until it changes to "Peterborough Cathedral" in the reign of King Henry VIII.

An important Mercian monastery

Royal foundation

Located in Mercia, near the border with East Anglia, Medeshamstede was described by Sir Frank Stenton as "one of the greatest monasteries of the Mercian kingdom".[12] Hugh Candidus, a 12th-century monk of Peterborough who wrote a history of the abbey, described its location as:

a fair spot, and a goodly, because on the one side it is rich in fenland, and in goodly waters, and on the other it has [an] abundance of ploughlands and woodlands, with many fertile meads and pastures.[13]

Hugh Candidus also reports that Medeshamstede was founded in the territory of the "Gyrwas", a people listed in the Tribal Hidage, which was in existence by the mid-9th century. There, the Gyrwas are divided into the North Gyrwas and the South Gyrwas: Medeshamstede was clearly founded in the territory of the North Gyrwas.[14] Hugh Candidus explains "Gyrwas", which he describes in the present tense, as meaning people "who dwell in the fen, or hard by the fen, since a deep bog is called in the Saxon tongue Gyr": use of the present tense indicates that inhabitants of the area were still known as "Gyrwas" in Hugh Candidus' own time.[13][15]

According to Bede, Medeshamstede was founded by a man named Seaxwulf, who was also its first abbot.[8] While it is possible that Seaxwulf was a local prince, Hugh Candidus described him as a "man of great power", and a man "zealous and [religious], and well skilled in the things of this world, and also in the affairs of the [Church]."[16] Historian, Dorothy Whitelock, believed that Seaxwulf had probably been educated in East Anglia, given the heathen state of Mercia prior to the mid-7th century.[17] He was later appointed Bishop of Mercia, and his near contemporary Eddius Stephanus mentions, in his Life of St Wilfrid, "the profound respect of the bishopric which the most reverend Bishop Seaxwulf had formerly ruled".[18]

A charter, dated 664 AD, records the gift by King Wulfhere of Mercia of "some additions" to the endowment for the monastery of Medeshamstede, already begun by his deceased brother King Peada of the Middle Angles, and by King Oswiu of Northumbria.[19] This charter is a forgery, produced for Peterborough Abbey either in the late 11th century, or in the early 12th; but, like Hugh Candidus, clearly it reflects Peterborough tradition, and it is both accurate and historically interesting in a number of ways, including in the chronology of kings.[20] The connection with Peada places Medeshamstede's foundation between about 653 and 656 AD.[21]

Numerous local saints are connected to varying degrees with Medeshamstede, and many of them are Mercian royal in nature. These include:

- Guthlac, a former monk of Repton, in Derbyshire. Repton had until recently been the Mercian episcopal see, and was most likely a colony of Medeshamstede. Guthlac is a titular saint of Crowland Abbey, about seven miles north of Medeshamstede, and is generally regarded as its founder.

- Pega, whose name survives in "Peakirk", meaning "church of Pega", about five miles north of Medeshamstede. She was a sister of Guthlac.[22]

- Cyneburh and Cyneswith, sisters of King Peada. Cyneburh founded a nunnery at Castor, four miles west of Medeshamstede, and Cyneswith succeeded her as abbess there.[23] It seems that both sisters had been married into foreign Anglo-Saxon royalty, in Northumbria and East Anglia, and perhaps Medeshamstede and Castor then formed a double monastery for men and women, a feature of contemporary monasticism. Cyneburh is the titular saint of the parish church of Castor, as "St Kyneburgha".

- Tibba, who is believed to have been a recluse at Ryhall, about twelve miles north west of Medeshamstede, as well as another relative of King Peada.[24]

- Tancred, Torhtred, and Tova: these are believed to have lived at Thorney, about five miles north east of Medeshamstede. It seems that Thorney was formerly known as Ancarig, a name which was preserved only at Peterborough, and itself suggests the presence there of anchorites.[25] Of these three saints, the first two were male, and the last is described as a female virgin; they are said to have been siblings, martyred during the late-9th-century Viking invasions.[26]

- Tondberht, "prince of the Gyrwas", and husband of St Æthelthryth of Ely. He is named as an English martyr in an early source, and, though nothing further is known of him, his name alliterates suggestively with those of Tancred, Torhtred and Tova, who thus may also have been drawn from local, petty royalty.[27]

- Tatwine, monk of Breedon, Archbishop of Canterbury, and probably mentor to Guthlac. Given his connection with Breedon, and his similarly alliterative name, he may himself have been from Medeshamstede, and would naturally have been commemorated there.[28]

Most if not all of the churches originally associated with these local saints were probably sponsored by Medeshamstede, with the exception of Ely.[15] What is known of Sexwulf, combined with the identities of these local saints, suggests strongly that Medeshamstede was a major religious centre in the kingdom of Mercia, with an especially royal character.

Monastic colonies

King Wulfhere's charter, and Bede's mention of Medeshamstede's foundation, place this in the period of the Christianisation of Mercia. Documents preserved at Peterborough Abbey indicate that Medeshamstede played a central role in spreading and consolidating Christianity in Mercia and elsewhere, for example through the pastoral care provided by a string of daughter churches.[29] Apart from churches connected with the local saints mentioned above, these are held to have included, among other candidates, churches at Breedon in Leicestershire, and Bermondsey and Woking, in Surrey.[30] Medeshamstede has also been identified as the mother church of Repton, in Derbyshire, which has been described as an 8th-century Mercian royal mausoleum.[31] Another charter preserved at Peterborough was written at Repton in 848 AD, and concerned Breedon.[32] This suggests that this monastic empire continued for some considerable time.[33] However, this is the latest surviving reference to any connection between Medeshamstede and its daughter churches, and these connections probably suffered a similar fate to many of the episcopal sees of eastern England: extinguished in the later 9th century by Viking invasion.[34]

The importance of these daughter churches, and indeed that of Medeshamstede itself, is indicated by the likely relationship with royal Repton; by the consecration of the Breedon monk Tatwine as Archbishop of Canterbury in 731 AD, and his later canonisation; and by St Guthlac's history as a former monk of Repton.

Later Anglo-Saxon history

Viking destruction

Medeshamstede is traditionally believed to have been destroyed by Vikings in 870 AD.[6] While this claim for Medeshamstede is derived from the Peterborough version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and from Hugh Candidus, both of which are 12th-century sources, destruction of churches by Vikings is a common feature in post-Conquest historiography. It is part of a consensus, developed from the time of the English monastic reformation of the 10th century, that Danish Vikings had been responsible for a long period of religious decline in England.[35] However, aspects of Medeshamstede's history, including the apparent survival of some of its pre-Viking archive, suggest that it did not suffer the same fate as other sites which were not so fortunate. According to S.E. Kelly,

[the] survival of a handful of genuine documents from the pre-tenth-century period [at Medeshamstede] might be better explained by the hypothesis that there was some kind of institutional continuity between the ninth century and the refoundation of c. 970, with the story of total destruction a convenient fiction.[36]

Tenth-century refoundation

Medeshamstede was refounded c. 970 by Bishop Æthelwold of Winchester, with the assistance of one Ealdwulf, who was the new monastery's first abbot, and later became bishop of Worcester and archbishop of York.[37] The monastery was soon enclosed within a massive stone wall, and acquired the new name of "Burh", meaning "fortified place".[38] The addition of the name "Peter", after the monastery's principal titular saint, served to distinguish it from similarly named places, such as the abbey at Bury St Edmunds, in Suffolk, and gave rise to the modern name "Peterborough".

Physical remains and archaeology

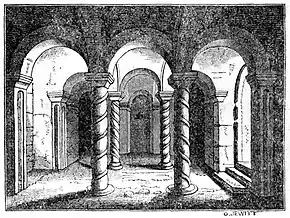

The most visible remnant of sculptural and architectural activity at Medeshamstede is the sculpture now known as the Hedda Stone, dated by Rosemary Cramp to the late eighth or early ninth century, and kept on show at Peterborough Cathedral.[39] Remnants of Anglo-Saxon buildings on the site of Medeshamstede have been identified in modern times, though it is not clear that any are remains of the original church.[40] These include foundations under the crossing and south transept of the Cathedral.

Early buildings on the site incorporated materials, or "spolia", removed from nearby Roman sites, such as the former town of Durobrivae, or possibly the very large villa at Castor.[41] Such spolia have also been identified in the foundations of later Anglo-Saxon structures on the site. Five hundred years after the event, Hugh Candidus wrote that when work on the church commenced, Sexwulf "laid as its foundations some great stones, so mighty that eight yoke of oxen could scarcely draw any of them", and claimed that Sexwulf and his colleagues were "striving to build no commonplace structure, but a second Rome, or a daughter of Rome in England".[42] This is reminiscent of Wilfrid's actions at Hexham.

References

- Emphasis on the syllable "ham" presumably follows the common interpretation of the name. If it is believed to mean "homestead belonging to Mede", then it would better be pronounced /ˈmiːdsˌhæmstɛd/.

- The most recent survey of the Anglo-Saxon history of Peterborough Abbey is in Kelly, S.E. (ed.), Charters of Peterborough Abbey, Anglo-Saxon Charters 14, OUP, 2009.

- The manuscript is the Peterborough "Liber Niger", or "Black Book", Society of Antiquaries of London, ms. 60 (f. 66).

- Ekwall, Eilert, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names (4th edition), 1960, p. 364.

- Saxonhistory.co.uk - Saxon Place names and their logical explanation

- A History of the County of Northampton: Volume 2, Serjeantson, R.M. & Adkins, W.R.D. (eds.), 1906. British History Online. Retrieved on 9 May 2008. A typically anachronistic account.

- Cf. Ekwall, Eilert, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names (4th edition), 1960, p. 320 ("Medstead").

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, iv, 6.

- Anglo-Saxon Charter S 34 Archive Rochester Archived 20 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine British Academy ASChart project. Retrieved on 11 May 2008. Anglo-Saxon charter references beginning with 'S', e.g. 'S 34', are to Sawyer, P., Anglo-Saxon Charters: an Annotated List and Bibliography, Royal Historical Society, 1968: see eSawyer.

- Ælfric, 'Vita Æthelwoldi', in Three Lives of English Saints, Winterbottom, M. (ed.), Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, Toronto, 1972, c.17. Dolley, R.H.M., 'A New Anglo-Saxon Mint – Medeshamstede', in British Numismatic Journal xxvii (3rd series, vii), 1955. These occurrences are probably related, and may represent an early corruption, which did not survive.

- A Topographical Dictionary of England, Lewis, Samuel (ed.), 1848. British History Online. Retrieved on 9 May 2008 (“Northamptonshire": uses the form "Medeshampstead").

- Stenton, F.M., 'Medeshamstede and its Colonies', in Stenton, D.M. (ed.), Preparatory to Anglo-Saxon England Being the Collected Papers of Frank Merry Stenton, Oxford University Press, 1970, p. 191.

- Mellows, W.T. (ed. & trans.), The Peterborough Chronicle of Hugh Candidus, Peterborough Natural History, Scientific and Archæological Society, 1941, p. 2. (This is a "popular" edition, in English translation (hereafter "Mellows, 1941"). A scholarly edition, in Latin, is Mellows, W.T. (ed.), The Chronicle of Hugh Candidus a Monk of Peterborough, Oxford University Press, 1949 (hereafter "Mellows, 1949")). Cf. Mellows, 1949, p. 5.

- Potts, W.T.W., 'The Pre-Danish Estate of Peterborough Abbey', in Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society 65, 1974: this paper contains some substantive errors, but is of interest. Cf. Hart., C., The Danelaw, Hambledon, 1992, pp. 142–3, for a similar comment regarding Medeshamstede, and Wilfrid's church at Oundle.

- Roffe, D., 'On Middan Gyrwan Fenne: Intercommoning around the Island of Crowland', in Fenland Research 8, 1993, p. 83.

- Mellows, 1941, pp. 3–4; Mellows, 1949, 8–9.

- Whitelock, D., 'The pre-Viking age church in East Anglia', in Anglo-Saxon England 1, 1972, pp. 38–41.

- Colgrave, B. (ed. & trans.), The Life of Bishop Wilfrid by Eddius Stephanus, Cambridge University Press, 1927 (reprinted 1985), c.xlv.

- "Anglo-Saxon Charter S 68 Archive Peterborough". British Academy ASChart project. Archived from the original on 20 July 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2008. This reference is to a later, grossly expanded version of the charter. A copy of what is no doubt the original version, modest by comparison, is printed as Birch, W. de Gray, Cartularium Saxonicum, 3 vols., London, 1885–93, no.22a.

- See Levison, W., England and the Continent in the Eighth Century The Ford Lectures Delivered in the University of Oxford in the Hilary Term 1943, Oxford University Press, 1946, pp. 217–9. Also Potts, W.T.W., 'The Pre-Danish Estate of Peterborough Abbey', in Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society 65, 1974. Rather than Medeshamstede's 'pre-Danish estate', the materials discussed by Potts probably identify a 7th-century tribal territory, which would be a unique survival: cf. Higham, N., 'The Historical Context of the Tribal Hidage', in Hill, D. and Rumble, A. R. (eds.), The Defence of Wessex: The Burghal Hidage and Anglo-Saxon Fortifications, Manchester University Press, 1996.

- "Peada (d. 656)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21682. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.). Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- Colgrave, B., The Life of St Guthlac by Felix, Cambridge University Press, 1956.

- 'The Life of St Kyneburgha From Northumbrian Queen to Mercian Saint', Morris, Avril M. (undated). Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Castor Church. Retrieved on 12 May 2008.

- Rollason, D.W., The Mildrith Legend A Study in Early Medieval Hagiography in England, Leicester University Press, 1982 (e.g. p. 115, in Medieval Latin).

- Mellows, 1941, p. 22; Mellows, 1949, pp. 42–3.

- Rollason, D.W., 'Lists of Saints' resting-places in Anglo-Saxon England', in Anglo-Saxon England 7, 1978, especially p. 91.

- Herzfeld, George, An Old English Martyrology: Re-edited from Manuscripts in the Libraries of the British Museum and of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Early English Text Society, 1900. For "prince of the Gyrwas", see Bede, Ecclesiastical History, iv, 19. For alliterative Old English personal names, see also Gelling, M., Signposts to the Past (2nd edition), Phillimore, 1988, pp. 163–4.

- A Tatwine is an important figure, local to the Fenland area, in Guthlac's "Life" by Felix. Roffe, in 'On Middan Gyrwan Fenne', p. 83, assumes that Crowland and Repton were both colonies of Medeshamstede.

- Blair, J. & Sharp, R. (eds.), Pastoral Care Before the Parish, Leicester University Press, 1992, especially p. 140. See also Yorke, B., Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, Seaby, 1990, p. 110.

- Stenton, F.M., 'Medeshamstede and its Colonies', in Stenton, D.M. (ed.), Preparatory to Anglo-Saxon England Being the Collected Papers of Frank Merry Stenton, Oxford University Press, 1970, and Blair, J., 'Frithuwold's kingdom and the origins of Surrey', in Bassett, S. (ed.), The Origins of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms, Leicester University Press, 1989. Other candidates, apart from Repton, are Bardney and Crowland, in Lincolnshire, Brixworth, in Northamptonshire, Hanbury, in Staffordshire, Hoo, in Kent, and Shifnal, in Shropshire.

- 'An Early History of Repton', Carroll, Quinton (undated). Repton Village History Group. Retrieved on 9 May 2008. Stafford, P., The East Midlands in the Early Middle Ages, Leicester University Press, 1985, especially pp. 106–8.

- "Anglo-Saxon Charter S 197 Archive Peterborough". British Academy ASChart project. Archived from the original on 20 July 2007. Retrieved 10 May 2008.

- For early medieval monastic empire building, see e.g. Colgrave, B. (ed. & trans.), The Life of Bishop Wilfrid by Eddius Stephanus, Cambridge University Press, 1927 (reprinted 1985), c.xxiv, Bede, Ecclesiastical History, iii, 4 ("St Columba"), and Farmer, D.H., The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (3rd edition), Oxford University Press, 1992, pp. 127–8 (“David of Wales”). Cf. Blair, J., 'Frithuwold's kingdom and the origins of Surrey', in Bassett, S. (ed.), The Origins of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms, Leicester University Press, 1989, p. 108.

- See e.g. Stafford, P., The East Midlands in the Early Middle Ages, Leicester University Press, 1985, p. 111.

- Gransden, A., Historical Writing in England Volume I c.550 – c.1307, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1974, p. 278. Principal movers of the 10th-century monastic reformation were St Dunstan, St Æthelwold of Winchester, and St Oswald of Worcester.

- Kelly, op. cit., p. 9. For a view of supposed Danish, anti-Christian activity, see e.g. Dumville, D.N., Wessex and England From Alfred to Edgar Six Essays on Political Cultural and Ecclesiastical Revival, Boydell, 1992, especially pp. 31-3, 39. For the pre-Viking archive, compare the situation at Abingdon, for which see ibid., especially p. 33, n.15: Dumville observes that the 12th-century chronicler of Abingdon "has the impudence to insist both on the destruction of the abbey [in the 9th century] and on the preservation of its charters and relics!"

- Kelly, op. cit., pp. 32, 36–9, 41–5.

- For the wall, see Youngs, S.M. & others, 'Medieval Britain and Ireland in 1982', in Medieval Archaeology 27, 1983. See e.g. Garmonsway, G.N., The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Dent, Dutton, 1972 & 1975, p. 117, where the change of name is linked to the construction of a wall around the monastery. Hugh Candidus describes the adoption of the new name, but does not link it to the construction of the monastic wall: Mellows, 1941, pp. 19, 24; Mellows, 1949, pp. 38, 48. Kelly, op. cit., pp. 5, 36–40, suggests that Medeshamstede might have been known as "Burh" prior to the mid-10th century, to distinguish it from the nearby Castor (cf. "Chester (place-name element)").

- Cramp, R., A century of Anglo-Saxon sculpture, Graham, 1977, p. 192. This date is subject to discussion: see Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland, "St Margaret, Fletton, Cambridgeshire". CRSBI. Retrieved 24 May 2008. The attribution to Hedda is a modern, antiquarian development, presumably based on a twelfth-century text known as the "Relatio Heddæ Abbatis" ("Story of Abbot Hedda"): Mellows, 1949, pp. 159–61. It is of extremely limited historical value, but was clearly a source used by Hugh Candidus, and is first found in a twelfth-century manuscript created at Peterborough called the "Liber Niger" ("Black Book": Society of Antiquaries of London, manuscript no.60, see e.g. Willetts, P.J., Catalogue of Manuscripts in the Society of Antiquaries of London , Boydell, Brewer, 2000).

- See e.g. Taylor, H.M. & J., "Peterborough, Northamptonshire", in their work Anglo-Saxon Architecture (3 vols.), CUP, 1965–78, II, pp. 491–4, and Youngs, S.M. et al., "Medieval Britain and Ireland in 1982", in Medieval Archaeology 27 (1983), pp. 168–9.

- British Archaeology Issue 60, August 2001, 'Old ruins, new world'. Archived 23 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine For the villa at Castor, see 'A Guide to the Church of St Kyneburgha Archived 23 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Castor Church. Retrieved on 25 May 2008.

- Mellows, 1941, pp. 3–4; Mellows, 1949, pp. 6, 8. At 2 oxen to the yoke, Hugh Candidus intended 16 oxen.