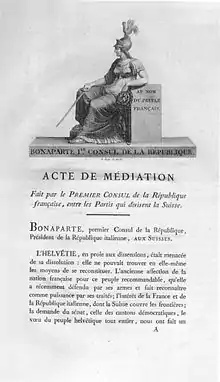

Act of Mediation

The Act of Mediation (French: Acte de Médiation) was issued by Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of the French Republic on 19 February 1803 to abolish the Helvetic Republic, which had existed since the invasion of Switzerland by French troops in 1798, and replace it with the Swiss Confederation. After the withdrawal of French troops in July 1802, the Republic collapsed (in the Stecklikrieg civil war). The Act of Mediation was Napoleon's attempt at a compromise between the Ancien Régime and a republic. This intermediary stage of Swiss history lasted until the Restoration of 1815. The Act also destroyed the statehood of Tarasp and gave it to Graubunden.

End of the Helvetic Republic

Following the French invasion of 1798, the decentralized and aristocratic Old Swiss Confederation was replaced with the highly centralized and republican Helvetic Republic. However the changes were too abrupt and sweeping and ignored the strong sense of identity that most Swiss had with their canton or city.[1] Throughout the following four years, French troops were often needed to support the Helvetic Republic against uprisings. The government of the Republic was also divided between the "Unitary" (supporting a single, strong central government) and the "Federalist" (supporting a Federation or self-governing cantons) parties. By 1802 a draft constitution was presented, but was quickly defeated in a popular vote in June 1802. In July Napoleon withdrew French troops from Switzerland, ostensibly to comply with the Treaty of Amiens, but really to show the Swiss that their best hopes lay in appealing to him.[1]

Following the withdrawal of French troops in the summer of 1802, the rural population (which was strongly Federalist) revolted against the Helvetic Republic. In the Canton of Léman, the Bourla-papey revolt broke out against the restoration of feudal land holdings and taxes.[2] While this rebellion was quieted through concessions, the following Stecklikrieg, so called because of the Stäckli or "wooden club" carried by the insurgents, led to the collapse of the Republic. After several hostile clashes with the official forces of the Helvetic Republic, which were lacking both in equipment and motivation (Renggpass at Pilatus on 28 August, artillery attacks on Bern and Zürich during September, and a skirmish at Faoug on 3 October), the central government at first capitulated militarily (on 18 September, retreating from Bern to Lausanne) and then collapsed entirely.[3]

Act of Mediation

With Napoleon acting as a mediator, representatives of the Swiss cantons met in Paris to end the conflict and officially dissolve the Helvetic Republic. When the Act of Mediation was produced on 19 February 1803 it attempted to address the issues that had torn the Republic apart and provide a framework for a new confederation under French influence. Much of the language of the Act was vague and unclear, which allowed the cantons considerable room for interpretation.[4]

In the preamble of the Act of Mediation Napoleon declared that the natural political state of the Swiss was as a Federation[4] and explained his role as a mediator.

The next 19 sections covered the 19 cantons that existed in Switzerland at the time. The original 13 members of the old Confederation were restored and 6 new cantons were added. Two of the new cantons (St Gallen and Graubünden or Grisons) were formerly "associates", while the four others were made up of subject lands (i.e. controlled by other cantons) that had been conquered at different times — Aargau (1415), Thurgau (1460), Ticino (1440, 1500, 1512), and Vaud (1536). Five of the six new cantons – Graubünden was the exception – were given modern representative governments. However, in the 13 original cantons many of the pre-revolutionary institutions remained in place. The landsgemeinden, or popular assemblies, were restored in the democratic cantons, the cantonal governments in other cases being in the hands of a great council (legislative) and the small council (executive). Overall, the powers granted to the state were extremely broad.[4]

The following 40 articles, which were known as the Acte fédéral or Acts of Confederation, defined the duties and powers of the federal government. The responsibilities of the Confederation included: providing equality for all citizens, creation of a Federal Army, the removal of internal trade barriers and international diplomacy. There were to be no privileged classes, burghers or subject lands. Switzerland was mentioned throughout the Act. Every Swiss citizen was now free to move and settle anywhere in the new Confederation.[1] The cantons guaranteed to respect each other's constitutions, borders and independence. The highest body of government was the Tagsatzung or Diet which was held in one of the six vororten (or leading cities, which were: Fribourg, Bern, Solothurn, Basel, Zürich and Lucerne) each year. The Diet was presided over by the Landammann der Schweiz who was the chief magistrate of the vorort in which the Diet met during that year. In the Diet, six cantons which had a population of more than 100,000 (Bern, Zürich, Vaud, St Gallen, Graubünden and Aargau) were given two votes, the others having but one apiece.

Two amendments to the Act, containing 13 and 9 articles, addressed the transition from the failed Republic to the new Confederation. Louis d'Affry, the appointed Landammann der Schweiz during the transition, was given extensive powers until the Diet could meet. Within the cantons, the local governments were run by a seven-member commission until new elections could be held.

The closing statement of the Act declared that Switzerland was an independent land and directed the new government to protect and defend the country.

End of the Mediation

The Act of Mediation was an important political victory for Napoleon. He was able to stop the instability of the Swiss from spreading into his emerging empire or weakening his army. The Act of Mediation created a pro-French buffer state with Austria and the German states. He even added the title Médiateur de la Confédération suisse (Mediator of the Swiss Confederation) to his others in 1809.[4]

While the Act of Mediation remained in force until the end of Napoleon's power in 1813 and was an important step in the development of the Swiss Confederation, the rights promised in the Act of Mediation soon began to vanish. In 1806 the principality of Neuchâtel was given to Marshal Berthier. Ticino was occupied by French troops from 1810 to 1813. Also, in 1810 the Valais was occupied and converted into the French department of the Simplon to secure the Simplon Pass. Swiss troops still served in foreign campaigns such as the French invasion of Russia which undermined their long-held neutrality. At home the liberty of moving from one canton to another (though given by the constitution) was, by the Diet in 1805, restricted by requiring ten years' residence, and then not granting political rights in the canton or a right of profiting by the communal property.

As soon as Napoleon's power began to wane (1812–1813), the position of Switzerland became endangered. The Austrians, supported by the reactionary party in Switzerland, and without any real resistance on the part of the Diet, crossed the border on 21 December 1813. On 29 December under pressure from Austria, the Diet abolished the 1803 constitution which had been created by Napoleon in the Act of Mediation.

On 6 April 1814 the so-called Long Diet met to replace the constitution. The Diet remained deadlocked until 12 September when Valais, Neuchâtel and Geneva were raised to full members of the Confederation. This increased the number of cantons to 22. The Diet, however, made little progress until the Congress of Vienna.[1]

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Bourla-Papey in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Stecklikrieg in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Act of Mediation in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.