Medical explanations of bewitchment

Medical explanations of bewitchment, especially as exhibited during the Salem witch trials but in other witch-hunts as well, have emerged because it is not widely believed today that symptoms of those claiming affliction were actually caused by bewitchment. The reported symptoms have been explored by a variety of researchers for possible biological and psychological origins.

Modern academic historians of witch-hunts generally consider medical explanations unsatisfactory in explaining the phenomenon and tend to believe the accusers in Salem were motivated by social factors – jealousy, spite, or a need for attention – and that the extreme behaviors exhibited were "counterfeit," as contemporary critics of the trials had suspected.

Ergot poisoning

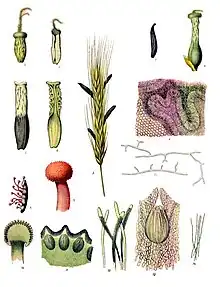

A widely known theory about the cause of the reported afflictions attributes the cause to the ingestion of bread that had been made from rye grain that had been infected by a fungus, Claviceps purpurea, commonly known as ergot. This fungus contains chemicals similar to those used in the synthetic psychedelic drug LSD. Convulsive ergotism causes a variety of symptoms, including nervous dysfunction.[1][2][3]

The theory was first widely publicized in 1976, when graduate student Linnda R. Caporael published an article[4] in Science, making the claim that the hallucinations of the afflicted girls could possibly have been the result of ingesting rye bread that had been made with moldy grain. Ergot of Rye is a plant disease caused by the fungus Claviceps purpurea, which Caporael claims is consistent with many of the physical symptoms of those alleged to be afflicted by witchcraft.

Within seven months, however, an article disagreeing with this theory was published in the same journal by Spanos and Gottlieb[5][6] They performed a wider assessment of the historical records, examining all the symptoms reported by those claiming affliction, among other things, that

- Ergot poisoning has additional symptoms that were not reported by those claiming affliction.

- If the poison was in the food supply, symptoms would have occurred on a house-by-house basis not in only certain individuals.

- Biological symptoms do not start and stop based on external cues, as described by witnesses, nor do biological symptoms start and stop simultaneously across a group of people, also as described by witnesses.

In 1989, Mary Matossian reopened the issue, supporting Caporeal, including putting an image of ergot-infected rye on the cover of her book, Poisons of the Past. Matossian disagreed with Spanos and Gottlieb, based on evidence from Boyer and Nissenbaum in Salem Possessed that indicated a geographical constraint to the reports of affliction within Salem Village.[7]

Encephalitis

In 1999, Laurie Winn Carlson offered an alternative medical theory, that those afflicted in Salem who claimed to have been bewitched, had encephalitis lethargica, a disease whose symptoms match some of what was reported in Salem and could have been spread by birds and other animals.[8]

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

It is possible that King Philip's War, concurrent with the Salem witch trials, induced PTSD in some of the "afflicted" accusers. Wabanaki allies of the French attacked British colonists in Maine, New Hampshire, and northern Massachusetts in a series of guerrilla skirmishes. Survivors blamed colonial leaders for the attacks' successes, accusing them of incompetence, cowardice, and corruption. A climate of fear and panic pervaded the northern coastline, causing a mass exodus to southern Massachusetts and beyond. Fleeing survivors from these attacks included some of the maidservant accusers in their childhood. Witnessing a violent attack is a trigger for hysteria and posttraumatic stress disorder.

Not only might the violence of the border skirmishes to the north explain symptoms of PTSD in accusers who formerly lived among the slaughtered, but the widespread blame of elite incompetence for those attacks offers a compelling explanation for the unusual demographic among the accused. Within the historical phenomenon, witch trial 'defendants' were overwhelmingly female, and members of the lower classes. The Salem witch trial breaks from this pattern. In the Salem witch trials, elite men were accused of witchcraft, some of them the same leaders who failed to successfully protect besieged settlements to the north. This anomaly in the pattern of typical witch trials, combined with widespread blame for the northern attacks on colonial leadership, suggests the relevance of the northern guerrilla attacks to the accusers. Thus, Mary Beth Norton, whose work draws the parallel between the Salem witch trials and King Philip's War, argues implicitly that a combination of PTSD and a popular societal narrative of betrayal-from-within caused the unusual characteristics of this particular witch trial.[9] [10] [11] [12]

Hysteria and psychosomatic disorders

The symptoms displayed by the afflicted in Salem are similar to those seen in classic cases of hysteria, according to Marion Starkey and Chadwick Hansen. Physicians have replaced the vague diagnosis of hysteria with what is essentially its synonym, psychosomatic disorder.[13][14]

Psychological processes known to influence physical health are now called "psychosomatic". They include:

- "several types of disease known as somatoform disorders, in which somatic symptoms appear either without any organic disorder or without organic damage that can account for the severity of the symptoms. ... A second type, conversion disorders, involves inexplicable malfunctions in motor and sensory systems. The third type, pain disorder, involves sensation either in the absence of an organic problem or in excess of actual physical damage."[15]

Psychologists Nicholas P. Spanos and Jack Gottlieb explain that the afflicted were enacting the roles that maintained their definition of themselves as bewitched, and this in turn led to the conviction of many of the accused that the symptoms, such as bites, pinches and pricks, were produced by specters. These symptoms were typically apparent throughout the community and caused an internal disease process.[16]

Starkey acknowledges that, while the afflicted girls were physically healthy before their fits began, they were not spiritually well because they were sickened from trying to cope with living in an adult world that did not cater to their needs as children. The basis for a Puritan society, which entails the possibility for sin, damnation, common internal quarrels, and the strict outlook on marriage, repressed the un-married teenagers who felt damnation was imminent. The young girls longed for freedom to move beyond their low status in society. The girls indulged in the forbidden conduct of fortune-telling with the Indian slave Tituba to discover who their future husbands were. They had hysteria as they tried to cope with,

- "the consequences of a conflict between conscience (or at least fear of discovery) and the unhallowed craving."[14]

Their symptoms of excessive weeping, silent states followed by violent screams, hiding under furniture, and hallucinations were a result of hysteria. Starkey conveys that after the crisis at Salem had calmed it was discovered that diagnosed insanity appeared in the Parris family. Ann Putnam Jr. had a history of family illness. Her mother experienced paranoid tendencies from previous tragedies in her life, and when Ann Jr. began to experience hysterical fits, her symptoms verged on psychotic. Starkey argues they had hysteria and as they began to receive more attention, used it as a means to rebel against the restrictions of Puritanism.

Hansen approaches the afflicted girls through a pathological lens arguing that the girls had clinical hysteria because of the fear of witchcraft, not witchcraft itself. The girls feared bewitchment and experienced symptoms that were all in the girls' heads. Hansen contests that,

- “if you believe in witchcraft and you discover that someone has been melting your wax image over a slow fire ... the probability is that you will get extremely sick – your symptoms will be psychosomatic rather than organic.”[13]

The girls suffered from what appeared to be bite marks and would often try to throw themselves into fires, classic symptoms of hysteria. Hansen explains that hysterics will often try to injure themselves, which never result in serious injuries because they wait until someone is present to stop them. He also concludes that skin lesions are the most common psychosomatic symptom among hysterics, which can resemble bite or pinch marks on the skin. Hansen believes the girls are not accountable for their actions because they were not consciously responsible in committing them.[13]

Projection

Historian John Demos in 1970[17] adopted a psycho-historical approach to confronting the unusual behavior displayed by the afflicted girls in Salem during 1692. Demos combined the disciplines of anthropology and psychology to propose that psychological projection could explain the violent fits the girls were experiencing during the crisis at Salem. Demos displays through charts that most of the accused were predominantly married or widowed women between the ages of forty-one and sixty, while the afflicted girls were primarily adolescent girls. The structure of the Puritan community created internal conflict among the young girls who felt controlled by the older women leading to internal feelings of resentment. Demos asserts that often neighborly relations within the Puritan community remained tense and most witchcraft episodes began after some sort of conflict or encounter between neighbors. The accusation of witchcraft was a scapegoat to display any suppressed anger and resentment felt. The violent fits and verbal attacks experienced at Salem were directly related to the process of projection, as Demos explains,

- The dynamic core of belief in witchcraft in early New England was the difficulty experienced by many individuals in finding ways to handle their own aggressive impulses in a Puritan culture. Aggression was thus denied in the self and attributed directly to others.[17]

Demos asserts that the violent fits displayed, often aimed at figures of authority, were attributed to bewitchment because it allowed the afflicted youth to project their repressed aggression and not be directly held responsible for their behaviors because they were coerced by the Devil. Therefore, aggression experienced because of witchcraft became an outlet and the violent fits and the physical attacks endured, inside and outside the courtroom, were examples of how each girl was undergoing the psychological process of projection.[17]

Flying ointment

"Flying ointment" or "witch's ointment" was a hallucinogenic ointment said to have been used in the practice of European witchcraft from at least as far back as the Early Modern period. Applying the ointment to the body caused hallucinations of flying and sexual experiences, and women who used the ointment were condemned as witches. Active ingredients in the ointment may have included monkshood and nightshade.[18]

References

- Woolf, Alan. (2000). Witchcraft or Mycotoxin? The Salem Witch Trials. Clinical Toxicology, 38 (4): 457-60, (July 2000).

- Video PBS Secrets of the Dead: "The Witches Curse" Archived 2014-04-19 at the Wayback Machine. Features an on-screen appearance by Linnda Caporeal.

- Sologuk, Sally. (2005). Diseases Can Bewitch Durum Millers. Milling Journal, Second Quarter 2005, pp. 44-45. available here

- Caporael, Linnda R. (1976). Ergotism: The Satan Loosed in Salem? Science, 192 (2 April 1976). see web page Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Spanos, Nicholas P. & Jack Gottlieb. (1976). Ergotism and the Salem Village witch trials. Science 24; 194 (4272): 1390-1394 (December 1976).

- Spanos, Nicholas P. (1983). Ergotism and the Salem witch panic: a critical analysis and an alternative conceptualization. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 19 (4): 358-369, (Oct 1983).

- Matossian, Mary Kilbourne. (1989). Chapter 9, "Ergot and the Salem Witchcraft Affair" In Poisons of the Past: Molds, Epidemics, and History, pp. 113-122 (ISBN 978-0300051216). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Carlson, Laurie Winn. (1999). A Fever in Salem: A New Interpretation of the New England Witch Trials, (ISBN 978-1566633093). Chicago, IL: Ivan R. Dee

- Beard, George M. 1971 (1882). The Psychology of the Salem Witchcraft Excitement of 1692 and its Practical Application to our own Time. Stratford, CT: John E. Edwards. See copy at Google Books

- Caulfield, Ernest. (1943). Pediatric Aspects of the Salem Witchcraft Tragedy. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 65, pp. 788–802 (May 1943). In Marc Mappen (ed.) (1996). Witches & Historians: Interpretations of Salem, 2nd ed. (ISBN 0-89464-999-X). Malbar, FL: Kreiger Publishing.

- Kences, James E. (2000). Some Unexplored Relationships of Essex County Witchcraft to the Indian Wars of 1675 and 1687. In Frances Hill (ed.). (1984). The Salem Witch Trials Reader, Essex Institute Historical Collections, DaCapo Press (July 1984).

- Mary Beth Norton points out that many of the afflicted girls were orphaned maidservants from the Maine frontier. These maidservants had lived through the attacks and were kin to many of those killed by the Wabanaki. Norton, Mary Beth. (2003). In the Devil's Snare. New York: Vintage.

- Chadwick Hansen. (1969). Witchcraft at Salem, p. 10. New York: George Braziller.

- Marion Starkey. (1949). The Devil in Massachusetts: A Modern Enquiry into the Salem Witch Trials, p. 39. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Bever, Edward. (2000). Witchcraft Fears and Psychosocial Factors in Disease. Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 30 (4): 577

- Spanos, Nicholas P. and Jack Gottlieb. (1976). Ergotism and the Salem Village Witch Trials. Science, 194 (4272).

- John Demos. (1970). Underlying Themes in the Witchcraft of Seventeenth-Century New England. The American Historical Review. 75 (5): 1311-1326.

- Forbes, Thomas R. (1962). "Midwifery and Witchcraft". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, XVII(2), 264–283. doi:10.1093/jhmas/xvii.2.264, p. 267-270