Climate categories in viticulture

In viticulture, the climates of wine regions are categorised based on the overall characteristics of the area's climate during the growing season.[1] While variations in macroclimate are acknowledged, the climates of most wine regions are categorised (somewhat loosely based on the Köppen climate classification) as being part of a Mediterranean (for example Tuscany[2][nb 1]), maritime (ex: Bordeaux[3]) or continental climate (ex: Columbia Valley[4]). The majority of the world's premium wine production takes place in one of these three climate categories in locations between the 30th parallel and 50th parallel in both the northern and southern hemisphere.[5] While viticulture does exist in some tropical climates, most notably Brazil, the amount of quality wine production in those areas is so small that the climate effect has not been as extensively studied as other categories.[6]

Influence of climate on viticulture

Beyond establishing whether or not viticulture can even be sustained in an area, the climatic influences of a particular area goes a long way in influencing the type of grape varieties grown in a region and the type of viticultural practices that will be used.[7] The presence of adequate sun, heat and water are all vital to the healthy growth and development of grapevines during the growing season. Additionally, continuing research has shed more light on the influence of dormancy that occurs after harvest when the grapevine essentially shuts down and reserves its energy for the beginning of the next year's growing cycle.

In general, grapevines thrive in temperate climates which grant the vines long, warm periods during the crucial flowering, fruit set and ripening periods.[8] The physiological processes of a lot of grapevines begin when temperatures reach around 10 °C (50 °F). Below this temperature, the vines are usually in a period of dormancy. Drastically below this temperature, such as the freezing point of 0 °C (32 °F) the vines can be damaged by frost. When the average daily temperature is between 17 and 20 °C (63 and 68 °F) the vine will begin flowering. When temperatures rise up to 27 °C (80 °F) many of the vine's physiological processes are in full stride as grape clusters begin to ripen on the vine. One of the characteristics that differentiates the various climate categories from one another is the occurrence and length of time that these optimal temperatures appear during the growing season.[9]

In addition to temperature, the amount of rainfall (and the need for supplemental irrigation) is another defining characteristics. On average, a grapevine needs around 710 mm (28 in) of water for sustenance during the growing season, not all of which may be provided by natural rain fall. In Mediterranean and many continental climates, the climate during the growing season may be quite dry and require additional irrigation. In contrast, maritime climates often suffer the opposite extreme of having too much rainfall during the growing season which poses its own viticultural hazards.[9]

Other climate factors such as wind, humidity, atmospheric pressure, sunlight as well as diurnal temperature variations—which can define different climate categories—can also have pronounced influences on the viticulture of an area.[8][9]

Mediterranean climates

Wine regions with Mediterranean climates are characterised by their long growing seasons of moderate to warm temperatures. Throughout the year there is little seasonal change, with temperatures in the winter generally warmer than those of maritime and continental climates. During the grapevine growing season, there is very little rainfall (with most precipitation occurring in the winter months) which increases the risk of the viticultural hazard of drought and may present the need for supplemental irrigation.[6]

The Mediterranean climate is most readily associated with the areas around the Mediterranean basin, where viticulture and winemaking first flourished on a large scale due to the influence of the Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans of the ancient world.[6]

Wine regions with Mediterranean climates

- Tuscany and most other Central-Southern Italian wine regions

- Liguria

- Marsala, Sicily

- Pantelleria

- Sardinia

- Most Greek wine regions

- Cyprus wine regions

- Israeli wine regions

- Jordanian wine regions

- Lebanese wine regions

- Palestinian wine regions

- Most Albanian wine regions

- Most Montenegrin wine regions

- Corsica

- Languedoc and Roussillon

- Provence

- Southern Rhone Valley

- Malta

- Andalusia including Jerez de la Frontera

- Balearic Islands

- Canary Islands (bordering tropical)

- Catalonia

- Jumilla, Spain

- Vinos de Madrid

- Most Portuguese wine regions

- Primorska Slovenian wine region (Cfa)

- Coastal Croatian wine regions (Cfa)

- Some Azerbaijani wine regions

- Napa Valley and other coastal California wine regions

- Southern Oregon AVA

- Baja California wine regions

- Western Australian and South Australian wine regions

- Chilean Central Valley

- Western coastal South African wine regions

- Western and southern coastal Turkish wine regions:

- Aegean Region

- Marmara Region (bordering maritime)

- Mediterranean Region

- Thracian Lowlands, Southern Bulgarian wine region (Cfa)

- Upper Struma Valley, Southwestern Bulgarian wine region (Cfa)

- Azores (bordering maritime)

- Madeira

- Algerian wine regions

- Egyptian wine regions (irrigated by the Nile system)

- Moroccan wine regions

- Tunisian wine regions

- Shiraz wine region, Iran (until 1979, since largely grown in Australia and South Africa)

Continental climates

.svg.png.webp)

Wine regions with continental climates are characterised by the very marked seasonal changes that occur throughout the growing season, with hot temperatures during the summer season and winters cold enough for periodic ice and snow. This is generally described as having a high degree of continentality. Regions with this type of climate are often found inland on continents without a significant body of water (such as an inland sea) that can moderate their temperatures. Often during the growing season continental climates will have wide diurnal temperature variations, with very warm temperatures during the day that drop drastically at night. During the winter and early spring months, frost and hail can be viticultural hazards. Depending on the particular macroclimate of the region, irrigation may be needed to supplement seasonal rainfall. These many climatic influences contribute to the wide vintage variation that is often typical of continental climates such as Burgundy.[6]

There are more wine regions with continental climates in the northern hemisphere than there are in the southern hemisphere. This is due, in part, to small land mass size of southern hemisphere continents relative to the large oceans nearby. This difference means that the oceans exert a more direct influence on the climate of the southern hemisphere wine regions (making them maritime or possibly Mediterranean) than they would on the larger northern hemisphere continents. There are also several wine regions (such as Spain) that have areas that exhibit a continental Mediterranean climate due to their altitude or distance from the sea. These regions will have more distinct seasonal change than Mediterranean climates, but still retain some characteristics like a long growing season that is very dry during the summer.[6]

Wine regions with continental climates

- Burgundy (maritime by US standards)

- Côte-Rôtie and other Northern Rhone wine regions (maritime by US standards)

- Jura wine region (maritime by US standards)

- Most of the Loire Valley (maritime by US standards)

- Rioja (Cfa/Cfb)

- Italian Piedmont and most other Northern Italian wine regions (Cfa/Cfb)

- Douro (Mediterranean by US standards)

- Saale-Unstrut, Germany

- Saxony

- Armenian wine regions

- Most Austrian wine regions

- Most Bulgarian wine regions

- Inland Croatia (Cfa/Cfb)

- Most Czech wine regions

- Most Hungarian wine regions

- Kazakh wine regions

- Most Macedonian wine regions (Cfa)

- Most Moldovan wine regions

- Polish wine regions

- Most Romanian wine regions

- Most Russian wine regions

- Most Serbian wine regions (Cfa/Cfb)

- Most Slovak wine regions

- Podravje and Posavje, Slovenia (maritime by US standards)

- Inland Turkish wine regions including Central Anatolia and Eastern Anatolia

- Most Ukrainian wine regions

- Sabile, Latvia

- Most Canadian wine regions (including Okanagan Valley, British Columbia and except western BC)

- Mendoza, Argentina (subtropical)

- Most of Central Delaware Valley AVA (PA/NJ)

- Columbia Valley (includes Walla Walla Valley (Csa) and Yakima Valley)

- Most of Cumberland Valley AVA (PA/MD)

- Eastern Connecticut Highlands AVA

- Finger Lakes, NY

- Grand Valley, Colorado

- Hudson River Region

- Lake Erie AVA (NY/PA/OH)

- Lake Michigan Shore AVA, Michigan

- Most of Lancaster Valley AVA, Pennsylvania

- Lehigh Valley AVA, Pennsylvania

- Missouri Rhineland

- Niagara Escarpment AVA, NY

- Most of Ohio River Valley AVA (IN/KY/OH/WV)

- Most of the Missouri portion of Ozark Mountain AVA

- Most of Snake River Valley AVA (Idaho/Oregon)

- Mainland Southeastern New England AVA (CT/MA/RI)

- Texas Davis Mountains AVA

- Texas High Plains AVA

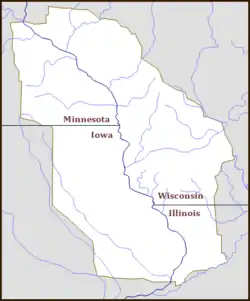

- Upper Mississippi River Valley AVA (IL/IA/MN/WI)

- Western Connecticut Highlands AVA

- Most Hokkaido wine regions

- Nagano Prefecture, Japan

- Tendō, Yamagata

- Yeongcheon wine region, North Gyeongsang Province, South Korea

- Yeongdong County, North Chungcheong Province, South Korea

- Beijing wine region

- Ningxia, China

- Xinjiang wine regions

- Yantai, China

- East of Cascade Range, Washington state, United States

- Central Otago wine region, New Zealand (maritime by US standards)

Maritime climates

Wine regions with maritime climates are characterised by their close proximity to large bodies of water (such as oceans, estuaries and inland seas) that moderate their temperatures. Maritime climates share many characteristics with both Mediterranean and continental climates and are often described as a "middle ground" between the two extremes.[10] Like Mediterranean climates, maritime climates have a long growing season, with water currents moderating the region's temperatures. However, Mediterranean climates are usually very dry during the growing season, and maritime climates are often subject to the viticultural hazards of excessive rain and humidity that may promote various grape diseases, such as mold and mildew. Like continental climates, maritime climates will have distinct seasonal changes, but they are usually not as drastic, with warm, rather than hot, summers and cool, rather than cold, winters.[6] Maritime climates also exist in some wine-growing areas of highlands of subtropical and tropical latitudes, including the southern Appalachian Mountains in the United States, the eastern Australian highlands and the central highlands of Mexico.

Wine regions with maritime climates

- Bordeaux

- Champagne

- Irouléguy AOC, Lower Navarre

- Madiran wine region, Gascony

- Muscadet

- Alsace and Lorraine (continental by French standards)

- Most German wine regions (continental by French standards)

- Liechtenstein wine regions (continental by French standards)

- Moselle Valley including Luxembourg (continental by French standards)

- Most Swiss wine regions (continental by French standards)

- Bizkaiko Txakolina, Basque Country

- Rías Baixas (Csb)

- New Zealand wine regions

- Southern Chile including Bío Bío Valley, Itata Valley, and Malleco Valley (Csb)

- Block Island, Cape Cod, Martha's Vineyard (Cfa), and Nantucket (all part of Southeastern New England AVA and bordering continental)

- Long Island (Cfa bordering continental, primarily east end, and including the North Fork and The Hamptons)

- North Fork of Roanoke, Virginia

- Puget Sound (Csb)

- Rocky Knob AVA, Virginia

- Some of Shenandoah Valley AVA (VA/WV)

- Upper Hiwassee Highlands (GA/NC)(mostly Cfa)

- Volcano Winery, Hawaii

- Willamette Valley (Csb)

- Alpine Valleys, Victoria

- Australian Pyrenees

- Bowral, New South Wales

- Most of Canberra District wine region

- Cowra highlands, New South Wales

- Fleurieu zone including Kangaroo Island and Langhorne Creek, South Australia (Csb)

- Gippsland, Victoria

- Grampians, Victoria

- Granite Belt, Queensland/NSW

- Heathcote wine region, Victoria

- Henty, Victoria

- Mudgee highlands, New South Wales

- Orange, New South Wales

- Port Phillip, Victoria (includes Mornington Peninsula and Yarra Valley)

- Tasmania

- Tumbarumba wine region, NSW (semi-arid)

- Fraser Valley, British Columbia

- Gulf Islands, BC

- Vancouver Island wine regions including Cowichan Valley, BC

- Médanos, Buenos Aires Province

- Río Negro Province, Argentina (semi-arid)

- Tarija wine region, Bolivia

- Caxias do Sul, Brazil

- São Joaquim, Brazil

- Eastern Cape wine-growing areas including St Francis Bay, South Africa

- KwaZulu-Natal highlands

- Mossel Bay, Western Cape, South Africa (semi-arid)

- Some highland Ethiopian wine regions

- Belgian wine regions

- Danish wine regions

- Dutch wine regions

- England and Wales

- Southern Ireland

- Some Georgian wine regions

- Some Abkhazian wine regions

- Some Crimean wine regions including Massandra

- Some Krasnodar Krai wine regions

- Some Black Sea Region Turkish wine regions

- Pico IPR, Pico, Azores, Portugal

- Da Lat, Vietnam

- Chã das Caldeiras, Cape Verde

- Areas of Aguascalientes, Guanajuato, Hidalgo, Querétaro, and Zacatecas, central highlands of Mexico

- Some Kashmir wine regions

- Thimphu wine region, Bhutan

- Matsumae Peninsula, Hokkaido

- West of Cascade Range, Washington state, United States (Csb)

See also

Notes

- Actually Central-Northern Tuscany has a Submediterranean climate (between Csa and Cfa, e.g. Florence), while coastal and southern zones belong to Mediterranean proper (Csa) climate.

References

- Fraga, H., Garcia de C. A. I., Malheiro, A.C., Santos, J.A., 2016. Modelling climate change impacts on viticultural yield, phenology and stress conditions in Europe. Global Change Biology: doi:10.1111/gcb.13382.

- S. Siddons "How the Tuscany Wine Region Works" TLC Cooking, Accessed: 18 January 2010

- M. Ewing-Mulligan "France's Bordeaux Wine Region" Dummies.com Reference page. Accessed: 18 January 2010

- A. Mumma "The Washington wine difference: it's in the vineyard" Wines & Vines, November 2005

- T. Stevenson "The Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia" pg 14-15 Dorling Kindersley 2005 ISBN 0-7566-1324-8

- J. Robinson (ed) "The Oxford Companion to Wine" Third Edition pg 179-195, 388, 428-434, 716-714 Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- Fraga, H., Santos, J.A., Malheiro, A.C., Oliveira, A.A., Moutinho-Pereira, J. and Jones, G.V., 2015. Climatic suitability of Portuguese grapevine varieties and climate change adaptation. Int. J. Clim.: doi:10.1002/joc.4325.

- H. Johnson & J. Robinson The World Atlas of Wine pg 20-21 Mitchell Beazley Publishing 2005 ISBN 1-84000-332-4

- K. MacNeil The Wine Bible pg 12-21 Workman Publishing 2001 ISBN 1-56305-434-5

- C. Fallis, editor The Encyclopedic Atlas of Wine pg 20-21 Global Book Publishing 2006 ISBN 1-74048-050-3