Pump organ

The pump organ is a type of free-reed organ that generates sound as air flows past a vibrating piece of thin metal in a frame. The piece of metal is called a reed. Specific types of pump organ include the reed organ, harmonium, and melodeon. The idea for the free reed was imported from China through Russia after 1750, and the first Western free-reed instrument was made in 1780 in Denmark.[1][2]

.jpg.webp)

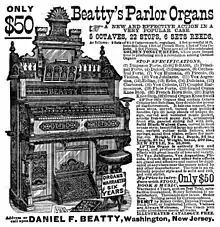

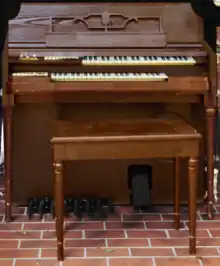

More portable than pipe organs, free-reed organs were widely used in smaller churches and in private homes in the 19th century, but their volume and tonal range were limited. They generally had one or sometimes two manuals, with pedal-boards being rare. The finer pump organs had a wider range of tones, and the cabinets of those intended for churches and affluent homes were often excellent pieces of furniture. Several million free-reed organs and melodeons were made in the US and Canada between the 1850s and the 1920s, some of which were exported.[3] The Cable Company, Estey Organ, and Mason & Hamlin were popular manufacturers.

Alongside the furniture-sized instruments of the west, smaller designs exist. The portable, hand-pumped harmonium or samvadini is a major instrument on the Indian subcontinent developed by Indians to meet local needs. The craftsmen created a harmonium that a single person could carry, with added microtones.

History

During the first half of the 18th century, a free-reed mouth organ called a sheng was brought to Russia.[1] That instrument received attention due to its use by Johann Wilde.[1] The instrument's free-reed was unknown in Europe at the time, and the concept quickly spread from Russia across Europe.[1] Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein (1723–1795), professor of physiology at Copenhagen, was credited with the first free-reed instrument made in the Western world, after winning the annual prize in 1780 from the Imperial Academy of St. Petersburg.[2] According to Curt Sachs, Kratzenstein suggested that the instrument be made, but that the first organ with free reeds was made by Abbé Georg Joseph Vogler in Darmstadt.[1] The harmonium's design incorporates free reeds and derives from the earlier regal. A harmonium-like instrument was exhibited by Gabriel-Joseph Grenié (1756–1837) in 1810. He called it an orgue expressif (expressive organ), because his instrument was capable of greater expression, as well as of producing a crescendo and diminuendo. Alexandre Debain improved Grenié's instrument and gave it the name harmonium when he patented his version in 1840.[4] There was concurrent development of similar instruments.[5] Jacob Alexandre and his son Édouard introduced the orgue mélodium in 1844. Hector Berlioz included it in his Grand traité d'instrumentation et d'orchestration modernes, published in Paris by Schoenberger, [1843?] or [1844?], in an « Instruments nouveaux » section on pp. 290–92, and in the 1856 reprint, found on pp. 472–77 in Peter Bloom's critical edition published by Bärenreiter, Vol.24, in Kassel and New York, 2003. Berlioz also wrote about it in several subsequent journals (Bloom, p. 472, nn. 1 & 2). He used it in 1 work: L'enfance du Christ, Part 1, scene vi, where it is off stage. When he conducted it in Weimar on 21 February 1855, it was played by Franz Liszt (Bloom, p. 474, n. 3).A mechanic who had worked in the factory of Alexandre in Paris emigrated to the United States and conceived the idea of a suction bellows, instead of the ordinary bellows that forced the air outward through the reeds. Beginning in 1885, the firm of Mason & Hamlin, of Boston made their instruments with the suction bellows, and this method of construction soon superseded all others in America.[4]

The term melodeon was applied to concert saloons in the Victorian American West because of the use of the reed instrument. The word became a common designation of that type of resort that offered entertainment to men.[6]

Harmoniums reached the height of their popularity in the West in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They were especially popular in small churches and chapels where a pipe organ would be too large or expensive; in the funeral-in-absentia scene from Mark Twain's The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, the protagonist narrates that the church procured a "melodeum" (a conflation, likely intended by Twain for satirical effect, of the names "melodeon" and "harmonium") for the occasion. Harmoniums generally weigh less than similar sized pianos and are not easily damaged in transport, thus they were also popular throughout the colonies of the European powers in this period not only because it was easier to ship the instrument out to where it was needed, but it was also easier to transport overland in areas where good-quality roads and railways may have been non-existent. An added attraction of the harmonium in tropical regions was that the instrument held its tune regardless of heat and humidity, unlike the piano. This "export" market was sufficiently lucrative for manufacturers to produce harmoniums with cases impregnated with chemicals to prevent woodworm and other damaging organisms found in the tropics.

.jpg.webp)

At the peak of the instruments' Western popularity around 1900, a wide variety of styles of harmoniums were being produced. These ranged from simple models with plain cases and only four or five stops (if any at all), up to large instruments with ornate cases, up to a dozen stops and other mechanisms such as couplers. Expensive harmoniums were often built to resemble pipe organs, with ranks of fake pipes attached to the top of the instrument. Small numbers of harmoniums were built with two manuals (keyboards). Some were even built with pedal keyboards, which required the use of an assistant to run the bellows or, for some of the later models, an electrical pump. These larger instruments were mainly intended for home use, such as allowing organists to practise on an instrument on the scale of a pipe organ, but without the physical size or volume of such an instrument. For missionaries, chaplains in the armed forces, travelling evangelist etc., reed organs that folded up into a container the size of a very large suitcase or small trunk were made; these had a short keyboard and few stops, but they were more than adequate for keeping hymn singers more or less on pitch.

The invention of the electronic organ in the mid-1930s spelled the end of the harmonium's success in the West, although its popularity as a household instrument had already declined in the 1920s as musical tastes changed . The Hammond organ could imitate the tonal quality and range of a pipe organ whilst retaining the compact dimensions and cost-effectiveness of the harmonium as well as reducing maintenance needs and allowing a greater number of stops and other features. By this time, harmoniums had reached high levels of mechanical complexity, not only through the demand for instruments with a greater tonal range, but also due to patent laws (especially in North America). It was common for manufacturers to patent the action mechanism used on their instruments, thus requiring any new manufacturer to develop their own version; as the number of manufacturers grew, this led to some instruments having hugely complex arrays of levers, cranks, rods and shafts, which made replacement with an electronic instrument even more attractive.

The last mass-producer of harmoniums in North America was the Estey company, which ceased manufacture in the mid-1950s; a couple of Italian companies continued into the 1970s. As the existing stock of instruments aged and spare parts became hard to find, more and more were either scrapped or sold. It was not uncommon for harmoniums to be "modernised" by having electric blowers fitted, often very unsympathetically. The majority of Western harmoniums today are in the hands of enthusiasts, though the instrument still remains popular in South Asia.

Modern electronic keyboards can emulate the sound of the pump organ.

Acoustics

The acoustical effects described below are a result of the free-reed mechanism. Therefore, they are essentially identical for the Western and Indian harmoniums and the reed organ. In 1875, Hermann von Helmholtz published his seminal book, On the Sensations of Tone, in which he used the harmonium extensively to test different tuning systems:[7]

"Among musical instruments, the harmonium, on account of its uniformly sustained tone, the piercing character of its quality of tone, and its tolerably distinct combinational tones, is particularly sensitive to inaccuracies of intonation. And as its vibrators also admit of a delicate and durable tuning, it appeared to me peculiarly suitable for experiments on a more perfect system of tones."[8]

Using two manuals and two differently tuned stop sets, he was able to simultaneously compare Pythagorean to just and to equal-tempered tunings and observe the degrees of inharmonicity inherent to the different temperaments. He subdivided the octave to 28 tones, to be able to perform modulations of 12 minor and 17 major keys in just intonation without going into harsh dissonance that is present with the standard octave division in this tuning.[9] This arrangement was difficult to play on.[10] Additional modified or novel instruments were used for experimental and educational purposes; notably, Bosanquet's Generalized keyboard was constructed in 1873 for use with a 53-tone scale. In practice, that harmonium was constructed with 84 keys, for convenience of fingering. Another famous reed organ that was evaluated was built by Poole.[11]

Lord Rayleigh also used the harmonium to devise a method for indirectly measuring frequency accurately, using approximated known equal temperament intervals and their overtone beats.[12] The harmonium had the advantage of providing clear overtones that enabled the reliable counting of beats by two listeners, one per note. However, Rayleigh acknowledged that maintaining constant pressure in the bellows is difficult and fluctuation of the pitch often occurs as a result.

In the generation of its tones, a reed organ is similar to an accordion or concertina, but not in its installation, as an accordion is held in both hands whereas a reed organ is usually positioned on the floor in a wooden casing (which might make it mistakable for a piano at the very first glimpse). Reed organs are operated either with pressure or with suction bellows. Pressure bellows permit a wider range to modify the volume, depending on whether the pedaling of the bellows is faster or slower. In North America and the United Kingdom, a reed organ with pressure bellows is referred to as a harmonium, whereas in continental Europe, any reed organ is called a harmonium regardless of whether it has pressure or suction bellows. As reed organs with pressure bellows were more difficult to produce and therefore more expensive, North American and British reed organs and melodeons generally use suction bellows and operate on vacuum.

Reed organ frequencies depend on the blowing pressure; the fundamental frequency decreases with medium pressure compared to low pressure, but it increases again at high pressures by several hertz for the bass notes measured.[13] American reed organ measurements showed a sinusoidal oscillation with sharp pressure transitions when the reed bends above and below its frame.[14] The fundamental itself is nearly the mechanical resonance frequency of the reed.[15] The overtones of the instrument are harmonics of the fundamental, rather than inharmonic,[16] although a weak inharmonic overtone (6.27f) was reported too.[17] The fundamental frequency comes from a transverse mode, whereas weaker higher transverse and torsional modes were measured too.[18] Any torsional modes are excited because of a slight asymmetry in the reed's construction. During attack, it was shown that the reed produces most strongly the fundamental, along with a second transverse or torsional mode, which are transient.[18]

Radiation patterns and coupling effects between the sound box and the reeds on the timbre appear not to have been studied to date.

The unusual reed-vibration physics have a direct effect on harmonium playing, as the control of its dynamics in playing is restricted and subtle. The free reed of the harmonium is riveted from a metal frame and is subjected to airflow, which is pumped from the bellows through the reservoir, pushing the reed and bringing it to self-exciting oscillation and to sound production in the direction of airflow.[14] This particular aerodynamics is nonlinear in that the maximum displacement amplitude in which the reed can vibrate is limited by fluctuations in damping forces, so that the resultant sound pressure is rather constant.[16] Additionally, there is a threshold pumping pressure, below which the reed vibration is minimal.[17] Within those two thresholds, there is an exponential growth and decay in time of reed amplitudes .[19]

Repertory

The harmonium was considered by Curt Sachs to be an important instrument for music of Romanticism (1750s-1900), which "vibrated between two poles of expression" and "required the overwhelming power and strong accents of wind instruments".[1]

Harmonium compositions are available by European and American composers of classical music. It was also used often in the folk music of the Appalachians and South of the United States.

Harmoniums played a significant part in the new rise of Nordic folk music, especially in Finland. In the late 1970s, a harmonium could be found in most schools where the bands met, and it became natural for the bands to include a harmonium in their setup. A typical folk band then—particularly in Western Finland—consisted of violin(s), double bass and harmonium. There was a practical limitation that prevented playing harmonium and accordion in the same band: harmoniums were tuned to 438 Hz, while accordions were tuned to 442 Hz.[20] Some key harmonium players in the new rise of Nordic folk have been Timo Alakotila and Milla Viljamaa.

In the Netherlands, the introduction of the harmonium triggered a boom in religious house music. Its organ-like sound quality allowed Reformed families to sing psalms and hymns at home. A lot of new hymns were composed expressly for voice and harmonium, notably those by Johannes de Heer.[21]

Western classical

The harmonium repertoire includes many pieces written originally for the church organ, which may be played on a harmonium as well, because they have a small enough range and use fewer stops. For example, Bach's Fantasia in C major for organ BWV 570 [22] is suitable for a four-octave harmonium.

Other examples include:

- Alban Berg. Altenberg Lieder

- William Bergsma. Dances from a New England Album, 1856 for orchestra. It includes parts for melodeon (movements I-III) and harmonium (movement IV).

- William Bolcom. Songs of Innocence and of Experience for orchestra, choirs, and soloists, includes parts for melodeon, harmonica, and harmonium.

- Anton Bruckner. Symphony no. 7, an arrangement for chamber ensemble, prepared in 1921 by students and associates of Arnold Schoenberg for the Viennese Society for Private Musical Performances, was scored for two violins, viola, cello, bass, clarinet, horn, piano 4-hands, and harmonium. The Society folded before the arrangement could be performed, and it went without premiere for more than 60 years.

- Frederic Clay. Ages Ago, an early work that features a harmonium part (libretto by W. S. Gilbert).

- Claude Debussy. Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune, a chamber ensemble arrangement by Arnold Schoenberg.

- Antonín Dvořák. Five Bagatelles for two violins, cello and harmonium, Op. 47 (B.79).

- Edward Elgar. Sospiri, Adagio for String Orchestra, Op. 70 (scored for harp or piano and harmonium or organ). Vesper Preludes.

- César Franck. The final collection of pieces popularly known as L'Organiste (1889–1890) was actually written for harmonium, with some pieces with piano accompaniment.

- Alexandre Guilmant, author of many duos for piano and harmonium, including:

- Symphonie tirée de la Symphonie-Cantate "Ariane" (Op. 53)

- Pastorale A-Dur (Op. 26)

- Finale alla Schumann sur un noël languedocien (Op. 83)

- Paul Hindemith. Hin und zurück (There and Back), an operatic sketch that uses a harmonium for its stage music.

- Sigfrid Karg-Elert. Various works for solo harmonium.

- Kronos Quartet. Early Music, an album that has several pieces featuring harmonium.

- Henri Letocart (1866–1945). 25 pieces for harmonium, Premier cahier.

- Franz Liszt. Symphonie zu Dantes Divina Commedia, Movement II: Purgatorio

- Gustav Mahler. Symphony No. 8

- George Frederick McKay. Sonata for Clarinet and Harmonium (1929) (also adaptable to piano or violin)

- Martijn Padding. First Harmonium Concerto (2008) for harmonium and ensemble [23]

- Gioachino Rossini. Petite messe solennelle is scored for twelve voices, two pianos and harmonium.

- Camille Saint-Saëns. The Barcarolle, Op. 108 is scored for piano, harmonium, violin and cello.

- Arnold Schoenberg

- Franz Schreker

- Chamber Symphony

- Vom ewigen Leben

- Richard Strauss. Ariadne auf Naxos an opera (libretto by Hugo von Hofmannsthal) that employs a harmonium in the orchestration of each of its versions. It requires an instrument with many stops, which are specified in the score.

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. "Manfred Symphony", fourth movement

- Louis Vierne. 24 Pièces en style libre pour orgue ou harmonium, Op. 31 (1913)

- Anton Webern. Five Pieces for Orchestra op.10

- Alexander Zemlinsky

- Six Maeterlinck Songs

- Lyric Symphony

Artists

.jpg.webp)

- Krishna Das, American kirtan singer, composer and recording artist

- Farrukh Fateh Ali Khan, Pakistani qawali performer, composer and recording artist

- Mariana Sadovska, Ukrainian singer, composer and recording artist

- Radie Peat, singer and musician of Lankum

Western popular music

.jpg.webp)

Harmoniums have been used in western popular music since at least the 1960s. John Lennon played a Mannborg harmonium[24] on the Beatles' hit single "We Can Work It Out", released in December 1965, and the band used the instrument on other songs recorded during the sessions for their Rubber Soul album.[25] They also used the instrument on the famous "final chord" of "A Day in the Life", and on the song "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!", both released on the 1967 album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[26] The group's hit single "Hello, Goodbye" and the track "Your Mother Should Know" were both written using a harmonium.[27][28]

Many other artists soon employed the instrument in their music, including; Pink Floyd on the title song "Chapter 24" of their first album The Piper at the Gates of Dawn in 1967, Elton John on his 1973 album Don't Shoot Me I'm Only the Piano Player, 1976's Blue Moves, the 1978 album A Single Man, and 1995's Made in England. German singer Nico was closely associated with the harmonium, using it as her main instrument, during the late 60s and 70s, on albums such as The Marble Index, Desertshore and The End....[29]

Donovan employed the harmonium on his 1968 album The Hurdy Gurdy Man where he played it in droning accompaniment on the song "Peregrine", and where it was also played on his song "Poor Cow" by John Cameron.[30]

Robert Fripp of King Crimson played a pedal harmonium borrowed from lyricist Peter Sinfield on the title track that progressive rock band's 1971 album Islands.

More recently Roger Hodgson from Supertramp used his harmonium on many of the group's songs including "Two of Us" from Crisis? What Crisis?, "Fool's Overture" from Even in the Quietest Moments..., the title track to their 1979 album Breakfast in America and "Lord Is It Mine". Hodgson also used a harmonium on "The Garden" from his 2000 solo album Open the Door. Greg Weeks and Tori Amos have both used the instrument on their recordings and live performances.

The Damned singer Dave Vanian bought a harmonium for £49 and used it to compose "Curtain Call", the 17-minute closing track from their 1980 double LP The Black Album. In 1990, Depeche Mode used a harmonium on a version of their song "Enjoy the Silence". The Divine Comedy used a harmonium on "Neptune's Daughter" from their 1994 album Promenade. Sara Bareilles used the harmonium on her 2012 song "Once Upon Another Time".[31]

During the 1990s the Hindu and Sikh-based devotional music known as kirtan, a 7th-8th century Indian music, popularly emerged in the West.[32][33] The harmonium is often played as the lead instrument by kirtan artists; notably Jai Uttal who was nominated for a Grammy award for new-age music in 2004,[32] Snatam Kaur, and Krishna Das who was nominated for a Grammy award for new age music in 2012.[34]

In the Indian subcontinent

The harmonium arrived in India during the mid-19th century, possibly with missionaries or traders.[35] The instrument quickly became popular there: it was portable, reliable and easy to learn.

The harmonium is popular to the present day, an important instrument in many genres of Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi music. For example, it is a staple of vocal North Indian classical music and Sufi Muslim Qawwali concerts.[36] It is commonly found in Indian homes. Though derived from the designs developed in France, the harmonium was developed further in India in unique ways, such as the addition of drone stops and a scale-changing mechanism. In Kolkata, Dwarkanath Ghose of the Dwarkin company modified the imported harmony flute and developed the hand-held harmonium, which has subsequently become an integral part of the Indian music scene.[37]

Dwijendranath Tagore is credited with having used the imported instrument in 1860 in his private theatre, but it was probably a pedal-pumped instrument that was cumbersome or possibly some variation of the reed organ. Initially, it aroused curiosity, but gradually people started playing it,[38] and Ghose took the initiative to modify it.[37] It was in response to the Indian needs that the hand-held harmonium was introduced. All Indian musical instruments are played with the musician sitting on the floor or a stage, behind the instrument or holding it in his hands. In that era, Indian homes did not use tables and chairs.[37] Also, in Western music, which is harmonically based, both a player's hands were needed to play the chords, thus assigning the bellows to the feet was the best solution; in Indian music, which is melodically based, only one hand was necessary to play the melody, and the other hand was free for the bellows.

The harmonium was widely accepted in Indian music, particularly Parsi and Marathi stage music, in the late 19th century. By the early 20th century, however, in the context of nationalist movements that sought to depict India as utterly separate from the West, the harmonium was portrayed as an unwanted foreigner. Technical concerns with the harmonium included its inability to produce slurs, gamaka (playing semi-tone between notes) and meend (slides between notes) which can be done in instruments like Sitar and Sarod,[35] and the fact that, as a keyboard instrument, it is set to specific pitches.[35] Unlike a stringed instrument, its pitches cannot be adjusted in the course of performance.

The inability to slide between notes prevents it from articulating the subtle inflections (such as andolan, gentle oscillation) so crucial to many ragas. Being set to specific pitches is a different musical concept than the Indian svara, which doesn't focus on specific pitches, but a range of pitches.[35] The fixed pitches prevent it from articulating the subtle differences in intonational color between a given svara in two different ragas.[35] For these reasons, it was banned from All India Radio from 1940 to 1971;[35] a ban still stands on harmonium solos.

On the other hand, many of the harmonium's qualities suited it very well for the newly reformed classical music of the early 20th century: it is easy for amateurs to learn; it supports group singing and large voice classes; it provides a template for standardized raga grammar; it is loud enough to provide a drone in a concert hall. For these reasons, it has become the instrument of choice for accompanying most North Indian classical vocal genres, with top vocalists (e.g., Bhimsen Joshi) routinely using harmonium accompaniment in their concerts. However, it is still despised by some connoisseurs of Indian music, who prefer the sarangi as an accompanying instrument for khyal singing.

A popular usage is by followers of the Hindu and Sikh faiths, who use it to accompany their devotional songs (bhajan and kirtan) respectively. There is at least one harmonium in any gurdwara (Sikh temple) around the world. The harmonium is commonly accompanied by the tabla as well as a dholak. To Sikhs, the harmonium is known as the vaja or baja. It is also referred to as a peti (literally, box) in some parts of North India and Maharashtra. The harmonium plays an integral part in Qawwali music. Almost all Qawwals use the harmonium as their sole musical accompaniment. It has received international exposure as the genre of Qawwali music has been popularized by renowned Pakistani musicians, including Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. There is some discussion of Indian harmonium makers producing reproductions of Western-style reed organs for the export trade.

Vidyadhar Oke has developed a 22-microtone harmonium, which can play 22 microtones as required in Indian classical music. The fundamental tone (Shadja) and the fifth (Pancham) are fixed, but the other ten notes have two microtones each, one higher and one lower. The higher microtone is selected by pulling out a knob below the key. In this way, the 22-shruti harmonium can be tuned for any particular raga by simply pulling out knobs wherever a higher shruti is required.

Bhishmadev Vedi is said to have been the first to contemplate improving the harmonium by augmenting it with a swarmandal (harp-like string box) attached to the top of the instrument. His disciple, Manohar Chimote, later implemented this concept, also making the instrument more responsive to key pressure, and called the instrument a samvadini—a name now widely accepted.[39] Bhishmadev Vedi is also said to have been among the first to contemplate and design compositions specifically for the harmonium, styled along the lines of "tantakari"—performance of music on stringed instruments. These compositions tend to have a lot of cut notes and high-speed passages, creating an effect similar to that of a string being plucked.

In 1954, Late Jogesh Chandra Biswas first modified the then-existing harmoniums, so it folds down into a much thinner space for easier maneuverability. Before that, if the instrument was boxed, it used to need two people to carry it, holding it from either side. This improvisation became a generic design in most harmoniums since then and was coined with the term "Folding Harmoniums".

The Shruti box, a keyless harmonium used only to produce drones to support other soloists.

Types

In the view points of preservation of cultural properties, maintenance and restoration, the pump organs are often categorized into several types.[40][41][42]

Historical instruments

Early instruments

Note: the term "melodium" seems to be interchangeable with the terms "melodion" and "melodeon".[43][44]

![Orgue-expressif [fr] (invented in 1810 by Gabriel-Joseph Grenié [fr], Paris) or Mélodium](../I/Musee_des_Ursulines_de_Quebec_010.jpg.webp)

_MET_DP227017.jpg.webp)

Seraphine (invented in 1833 by John Green, London)

Seraphine (invented in 1833 by John Green, London)](../I/Harmoniflute%252C_Technisches_Museum_Wien.jpg.webp)

Harmonium

Harmoniums are pressure system free-reed organs.

Flattop harmonium (c. 1865) by Alexandre Debain, a French inventor of the harmonium (patented in 1842)[46]

Flattop harmonium (c. 1865) by Alexandre Debain, a French inventor of the harmonium (patented in 1842)[46]![Kunstharmonium [de] (French: harmoniums d’art) with Celesta, by Auguste Victor Mustel [fr], Paris (1890)](../I/Orgue-C%C3%A9lesta.gif)

![Piano-mélodium [fr] and Orgue-mélodium (invented in mid-19th c. by Alexandre Père et Fils [fr])](../I/Orgues-m%C3%A9lodium_d'Alexandre_p%C3%A8re_et_fils.jpg.webp)

![Portable harmonium: Indian harmonium or Guide-chant [fr]](../I/Pakistani_Qawwali_Harmonium.jpg.webp) Portable harmonium: Indian harmonium or Guide-chant[42] is often played with the various ragas of Indian classical music.

Portable harmonium: Indian harmonium or Guide-chant[42] is often played with the various ragas of Indian classical music. Chapel harmonium

Chapel harmonium![Two manual with pedal harmonium by Theodor Mannborg [de] (1911)](../I/Organeum%252C_Weener_-_15.JPG.webp) Two manual with pedal harmonium[40] by Theodor Mannborg (1911)

Two manual with pedal harmonium[40] by Theodor Mannborg (1911) Enharmonic harmonium: Orthotonophonium (1870s/1914)

Enharmonic harmonium: Orthotonophonium (1870s/1914)

Suction reed organs

Suction reed organs are vacuum system free-reed organs.

Melodeons and Seraphines

Note: The term "melodeon" seems to be interchangeable with the terms "melodion" and "melodium".[43][44]

- For the type of accordion, see Diatonic button accordion § Nomenclature.

Seraphine[42] of the United States (ca.1835 by James A. Bazin, MA)

Seraphine[42] of the United States (ca.1835 by James A. Bazin, MA).jpg.webp)

Reed organs

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Enharmonic reed organ (1868/1871)

Enharmonic reed organ (1868/1871)

by Joseph Alley

Later instruments (electric-fan driven / electronic organs)

Electric-fan driven reed organ

Electric-fan driven reed organ.jpg.webp) Electric-fan driven reed chord organ (1960s)

Electric-fan driven reed chord organ (1960s) Electrostatic-pickup reed organ (1930s–60s)

Electrostatic-pickup reed organ (1930s–60s) cf. Electronic organ (1939–)

cf. Electronic organ (1939–)

Related instruments

References

- Sachs, Kurt (1940). The History of Musical Instruments. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 184, 406–407.

- Missin, P. R. "Western Free Reed Instruments". Retrieved 2010-08-06.

- "Carpenter Organ Company (1899)". Vermont Phoenix. 1899-09-01. p. 4. Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- "History of the reed organ". Retrieved 2010-08-06.

- Asbury, Herbert, The Barbary Coast, (Alfred Knopf, 1933), 105

- Helmholtz, L. F., and Ellis, A., On the Sensations of Tone, London: Longmans, Green, And Co., 1875.

- Helmholtz, H. L. F., 1875, p. 492, Part III, Justly-Intoned Harmonium.

- Helmholtz, H. L. F., 1875, p. 634, Appendix. XVII.

- Helmholtz, H. L. F., 1875, p. 682, Appendix. XIX.

- Helmholtz, H. L. F., 1875, p. 677, Appendix. XIX.

- Rayleigh (Jan 1879). "On the determination of absolute pitch by the common harmonium". Nature. 19 (482): 275–276. Bibcode:1879Natur..19R.275.. doi:10.1038/019275c0.

- Cottingham, J. P., Reed, C. H. & Busha, M. (Mar 1999). Variation of frequency with blowing pressure for an air-driven free reed (PDF). Collected Papers of the 137th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America and the 2nd Convention of the European Acoustics Association: Forum Acusticum, Berlin. Vol. 105. p. 1001. Bibcode:1999ASAJ..105R1001C. doi:10.1121/1.425800. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-26. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cottingham, J. P. (Sep 2007). "Reed Vibration in Western Free-Reed Instruments" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Congress on Acoustics (ICA2007), Madrid, Spain. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-26. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- Fletcher, N. H. & Rossing, T. D. (1998). The physics of musical instruments, 2nd ed. Springer Science+Media Inc. p. 414.

- St. Hilaire; A. O. (1976). "Analytical prediction of the non-linear response of a self-excited structure". Journal of Sound and Vibration. 47 (2): 185–205. Bibcode:1976JSV....47..185S. doi:10.1016/0022-460x(76)90717-3.

- Cottingham, J. P., Lilly, J. & Reed, C. H. (Mar 1999). The motion of air-driven free reeds (PDF). Collected Papers of the 137th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America and the 2nd Convention of the European Acoustics Association: Forum Acusticum, Berlin. Vol. 105. p. 940. Bibcode:1999ASAJ..105..940C. doi:10.1121/1.426334. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-26. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Paquette, A & Cottingham, J. P. (Nov 2003). Modes of Vibration of Air-driven Free Reeds in Steady State and Transient Oscillation (PDF). 137th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, Austin Texas. doi:10.1121/1.4781137. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-26. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- St. Hilaire, A. O., Wilson, T. A. & Beavers, G. B. (1971). "Aerodynamic excitation of the harmonium reed". Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 49 (4): 803–816. Bibcode:1971JFM....49..803H. doi:10.1017/s0022112071002374. S2CID 121955334.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Harmooni" (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- Jan Smelik, "Stichtelijke zang rond het harmonium" in: Louis Grijp c.s., Een muziekgeschiedenis der Nederlanden. Amsterdam University Press/Salome, Amsterdam, 2001: pp. 547-52.

- "Fantasia in C major, BWV 570 (Bach, Johann Sebastian) - IMSLP/Petrucci Music Library: Free Public Domain Sheet Music". Imslp.org. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- "Martijn Padding". Martijnpadding.nl. Archived from the original on 2013-02-22. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- O'Keefe, Phil (7 February 2014). "Keyboards of the Beatles Era". Harmony Central. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Everett, Walter (2001). The Beatles as Musicians: The Quarry Men through Rubber Soul. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 321–22. ISBN 0-19-514105-9.

- Emerick, Geoff; Massey, Howard (2006). Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of the Beatles. New York, New York: Gotham Books. pp. 162–167. ISBN 978-1-592-40269-4.

- "Hello, Goodbye". The Beatles Bible. 15 March 2008. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- Scapelliti, Christopher (Editor, Writer) (2016). "Music Icons - The Beatles: The Story Behind Every Album & Song". New York, NY: Athlon Sports Communications, Inc.: 84.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help);|author1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Desertshore - Nico | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- "The Hurdy Gurdy Man". Donovan Unofficial. 2009. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- Goosee9 (15 May 2013). "Sara Bareilles - Once Upon Another Time (Live at the El Rey - 5/14/2013)". Archived from the original on 2021-11-07 – via YouTube.

- Shannon Sexton; Anna Dubrovsky (December 16, 2011). "Sing the Soul Electric". Yoga Journal.

- Rockwell, Teed (November 14, 2011). "Kirtans East and West". India Currents. Archived from the original on December 24, 2015.

- Patoine, Brenda (December 6, 2012). "Krishna Das' "Live Ananda" Earns Grammy Nomination; Kirtan Grammy Would Be A First". The Bhakti Beat.

- "Small encyclopedia with Indian instruments". india-instruments.com.

excerpt of Suneera Kasliwal, Classical Musical Instruments, Delhi 2001

- Jones, L. JaFran (1990). "Review of Sufi Music of India and Pakistan.: Sound, Context and Meaning in Qawwali". Asian Music. 21 (2): 151–155. doi:10.2307/834116. ISSN 0044-9202. JSTOR 834116.

- "The Invention of Hand Harmonium". Dwarkin & Sons (P) Ltd. Archived from the original on 2007-04-09. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- Khan, Mobarak Hossain (2012). "Harmonium". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- "About Samvadini". Sydney: Samvad (music centre). Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- Fudge, Rod. "Twelve Different Types of Pump Organs (Types of Reed Organs)". PumpOrganRestorations.com.

- "How To Find Serial Numbers In Estey Reed Organs". Estey Organ Museum. Archived from the original on 2015-01-01.

- "6.Annexes. A.Typologie". Guide - Harmoniums : Repérage et protection au titre des monuments historique [Guide - Harmoniums : Identification and protection as historical monuments] (PDF). Direction générale des patrimoines [Directorate General of Heritage] (in French). Paris, France: Ministère de la Culture. 2020. pp. 21–26. ISBN 978-2-11-162589-1.

- Köhler, Friedrich; Lambeck, Hermann (1892). Lambeck, Hermann (ed.). Dictionary of the English and German Languages. P. Reclam jun. p. 307.

"melodeon [me-lō'di-on] s. ♪ Ziehharmonica f. Melodion n (=melodium).

melodium [me-lō'di-um] s. Melodion n (=melodeon)." - The Century Dictionary. An Encyclopedic Lexicon of the English Language. Vol. 13. Century Company. 1890. p. 3700.

"melodeon (me-ˈlō'di-on). n. [Also melodium; < L. melodia, < Gr. μελωδία, a singing: see melody. Cf. melodion.] A reed-organ or harmonium.

melodium (me-lō'di-um). n. See melodeon." - Gilbert Hirsch (2018-03-18). Harmoniflûte de Mayermatrix [1850] (video). YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. — an example of harmoniflûte play. The bellow on rear-side is pumped by a foot pedal located between a stand.

- Stichwort. "Harmonium". Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (MGG). Vol. 5. p. 1708.

- Давида ЯКОБАШВИЛИ [David Iakobachvili]. "Harmonium "Reform-orgel" (1888–1903, Sweden, Karlstad) by J.P. Nyströms Orgel & Pianofabrik [Inv. 101/MMP]". Музей "Собрание" [Muzey "Sobraniye" / Museum COLLECTION].

Mechanical harmonium in piano shaped wooden case ... The inscription "I.P. Nyström" is on the left side, 'Reform-Orgel Patent" – is in the center, "Karlstad" is on the right side. Framed text "Jnnehar sjutton (17) Patenter å egna Uppfinningar inom orgelbranchen" (17 patents for original inventions in the organ industry) is beneath the central inscription. ...

- Waring, Dennis G. (29 July 2002). "American Reed Organ Manufacture". Manufacturing the Muse: Estey Organs and Consumer Culture in Victorian America. Wesleyan University Press (published 2002). pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-8195-6508-2.

- Bush, Douglas Earl; Kassel, Richard (2006). "Prescott, Abraham (1789–1858)". The Organ: An Encyclopedia. Encyclopedia of keyboard instruments. Vol. 3. Psychology Press. p. 441. ISBN 9780415941747.

- Prescott, Abraham (1825), Rocking Melodeon, MET Accession Number: 89.4.1194,

Maker: Abraham Prescott (American, Deerfield, New Hampshire 1789–1858 Concord, New Hampshire)

- Laurence Libin (Summer 1989). "Keyboard Instruments" (PDF). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 47 (1): 52. (available as PDF)

- "New Haven Melodeon (1865)". AntiquePianoShop.com. 26 August 2017.

This is a beautiful melodeon built by The New Haven Melodeon Company circa about 1865. These instruments are small reed organs that are operated by pumping the large iron right pedal…the left pedal is volume control and operates a swell shutter. During the mid 19th Century, these little melodeons were often the only form of musical entertainment in Rural America. This style of melodeon is known as a "Portable Melodeon" and its legs are designed to fold up under the instrument for easy transport. ...

See images: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. - "New Haven Melodeon Company". AntiquePianoShop.com. September 2017.

The New Haven Melodeon Company was organized on April 10th, 1867 in New Haven, CT. John L. Treat of Treat & Linsley was listed as superintendent of the firm. The firm built several models of organs and melodeons and enjoyed a great deal of success. By 1872 the firm is listed as having operating capital in the amount of $40,000. By the late 1870s, the popularity of the melodeon began to wain in favor of the parlor organ. The firm reorganized as "The New Haven Organ Company" from 1881 – 1883, and there is no mention of the firm after about 1883.

See also: Treat & Linsley. - "The Olthof Collection - Exhibited in 1981". harmoniumnet.nl.

17. Flat top reed organ by George Woods & Co. This firms is known for its high quality Melodeons (early type of reed organ, in fact the suction variety of the physharmonica)

- Autophone (1878), "Autophone" Organette, Henry Bishop Horton (inventor), MET Accession Number: 07.195a, b,

Manufacturer: Autophone / Inventor: Henry Bishop Horton (American, Winchester, Connecticut 1819–1885)

External links

- The Reed Organ Society

- The Reed Organ Home Page of John K. Estell, Ohio Northern University

- Top Harmonium Makers

![cf. Symphonium [de] circa 1830(invented c.1829)](../I/Mouth_organ_(or_symphonium)_(c.1830%252C_London)_by_Charles_Wheatstone%252C_Museum_of_Fine_Arts%252C_Boston.jpg.webp)