Abu Mena

Abu Mena (also spelled Abu Mina; Coptic: ⲁⲃⲃⲁ ⲙⲏⲛⲁ; Arabic: أبو مينا pronounced [æbuˈmæyːnæ]) was a town, monastery complex and Christian pilgrimage centre in Late Antique Egypt, about 50 km (31 mi) southwest of Alexandria, near New Borg El Arab city. Its remains were designated a World Heritage Site in 1979 for the site's importance in early Christianity.[1] There are very few standing remains, but the foundations of most major buildings, such as the great basilica, are easily discernible.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Location | Alexandria Governorate, Egypt |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iv) |

| Reference | 90 |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| Endangered | 2001– |

| Area | 83.63 ha (0.3229 sq mi) |

| Coordinates | 30°50′28″N 29°39′49″E |

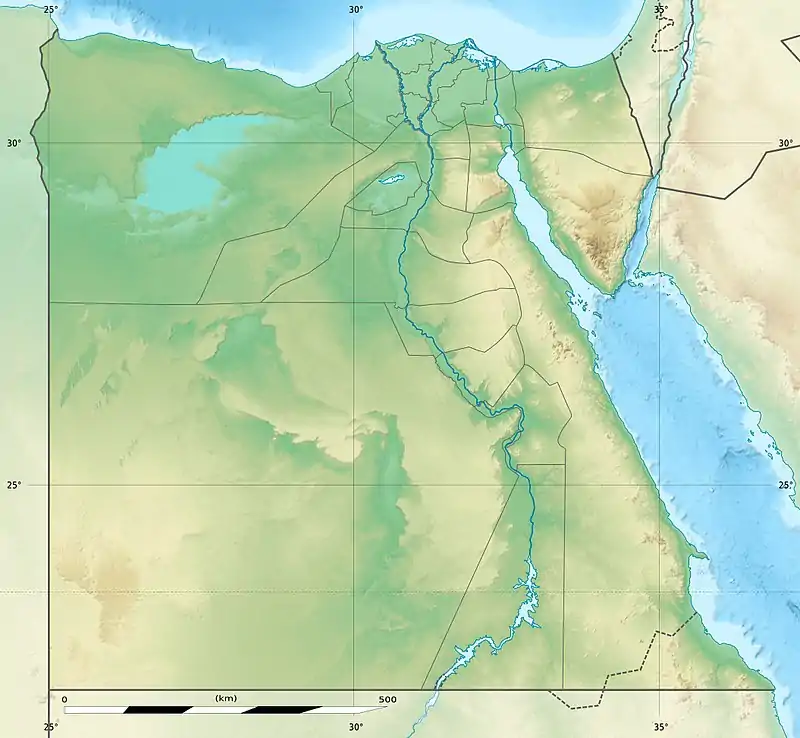

Location of Abu Mena in Egypt | |

Recent agricultural efforts in the area have led to a significant rise in the water table, which has caused a number of the site's buildings to collapse or become unstable. The site was added to the List of World Heritage in Danger in 2001. Authorities were forced to place sand in the bases of buildings that are most endangered in the site.

History

Menas of Alexandria was martyred in the late 3rd or early 4th century (see Early Christianity).[2]: 16 Various 5th-century and later accounts give slightly differing versions of his burial and the subsequent founding of his church. The essential elements are that his body was taken from Alexandria on a camel, which was led into the desert beyond Lake Mareotis. At some point, the camel refused to continue walking, despite all efforts to goad it. This was taken as a sign of divine will, and the body's attendants buried it on that spot.

Most versions of the story state that the location of the tomb was then forgotten until its miraculous rediscovery by a local shepherd. From the Ethiopian Synaxarium (E.A.W. Budge, trans.):

And God wished to reveal the [place of the] body of Saint Mînâs. And there was in that desert a certain shepherd, and one day a sheep which was suffering from the disease of the scab went to that place, and dipped himself in the water of the little spring which was near the place, and he rolled about in it and was healed straightway. And when the shepherd saw this thing, and understood the miracle, he marvelled exceedingly and was astonished. And afterwards he used to take some of the dust from that shrine, and mix it with water, and rub it on the sheep, and if they were ill with the scab, they were straightway healed thereby. And this he used to do at all times, and he healed all the sick who came to him by this means.

Word of the shepherd's healing powers spread rapidly. The synaxarium describes Constantine I sending his sick daughter to the shepherd to be cured, and credits her with finding Menas' body, after which Constantine ordered the construction of a church at the site. (Some versions of the story replace Constantine with the late-5th century emperor Zeno, but archaeologists have dated the original foundation to the late 4th century).[3] By the late 4th century, it was a significant pilgrimage site named Martyroupolis,[4] where Christians sought healing and other miracles.[5][6] Menas flasks are a particular type of small terracotta ampullae sold to pilgrims as containers for holy water or holy vigillamp-oil which are found very widely around the Western Mediterranean, dating roughly from the century and a half before the Muslim conquest. They are cheaply made but impressed with images of the saint that are of significance in the study of iconography; it is presumed they were made around the city.[7]

During the reign of Arcadius, the local archbishop observed that crowds were overwhelming the small church. He wrote to the eastern emperor, who ordered a major expansion of the facilities, the first of three major church expansions which would eventually take place. By the end of Late antiquity, Abu Mena had become the leading pilgrimage site in Egypt.[8][9]

Abu Mena was destroyed during the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century.

Archaeological excavations

The site was first excavated from 1905 to 1907. These efforts uncovered a large basilica church, an adjacent church which had probably housed the saint's remains, and Roman baths.[10]

A later, long-term series of excavations by the DAI ended in 1998. The most recent excavations uncovered a large dormitory for poor pilgrims, with separate wings for men and for women and children. A complex to the south of the great basilica was likely the residence of the hegoumenos, or abbot. Excavations suggest that the great xenodocheion, a reception area for pilgrims, may originally have been a cemetery. A baptistery, adjacent to the site of the original church, appears to have gone through at least three phases of development. Also uncovered was a complex of wine presses, including underground storage rooms, which dates to the 6th and 7th centuries.[8]

Threats

The site of Abu Mena was added to UNESCO's World Heritage in Danger list in 2001 due to the threat of rising local water tables. This rise in water is due to agricultural development programs aimed at reclaiming the land. The hard clay soil that surrounds the site can support buildings when dry. However, it becomes unstable when wet and has led to the collapse of cisterns and other structures about the ancient city.[11] As the ground collapses, large cavities form enveloping the overlying structures.

Immediate action was taken to fill the bases of particularly important sites with sand and close them off to the public. In attempts to counteract this phenomenon, the Supreme Council of Antiquities spent 45 million digging trenches and adding pumps in hopes of decreasing the pressure of irrigation. In addition, a fence was added to prevent encroachment and threat.[12] These proved to be successful and the site was removed from UNESCO's World Heritage in Danger list in 2009.[13]

Since then, water has continued to rise and cause destruction of monuments. The site is once again on UNESCO's World Heritage in Danger list. Factors found to negatively impact the property most recently in 2018 include housing, management activities, managements systems/plan, and water. [14]

Conservation

The Egyptian government has implemented emergency plans and indeed solved the problem with the water table, but the government does not currently have a thorough management plan or anything related to it. Since UNESCO requires a management plan for all the cultural and natural sites, several proposals have been made. The most reliable option is the use of a smart, sustainable membrane. It has been designed to solve issues with ventilation, energy, and water on the site. This plan involves building a dome-shaped smart membrane, which would provide the site an appropriate amount of airflow (as is required for every world heritage site). The smart-membrane dome would also provide a self-sustainable energy supply through solar cells located on the outside layer of the dome. The membrane would also be designed to have a filtration system for dehumidifying the air by filtering the water out of it so that the site can be better preserved.[15]

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Artifacts at Abu Mena

Artifacts at Abu Mena.jpg.webp) Artifacts at Abu Mena

Artifacts at Abu Mena.jpg.webp) Artifacts at Abu Mena

Artifacts at Abu Mena.jpg.webp) Basilica of The Crypt at Abu Mena

Basilica of The Crypt at Abu Mena.jpg.webp) Basilica of The Crypt at Abu Mena

Basilica of The Crypt at Abu Mena.jpg.webp) Basilica of The Crypt at Abu Mena

Basilica of The Crypt at Abu Mena.jpg.webp) Baths at Abu Mena

Baths at Abu Mena.jpg.webp) Baths at Abu Mena

Baths at Abu Mena.jpg.webp) Baths at Abu Mena

Baths at Abu Mena.jpg.webp) Landscape at Abu Mena

Landscape at Abu Mena.jpg.webp) Pilgrimage Centre at Abu Mena

Pilgrimage Centre at Abu Mena.jpg.webp) Pilgrimage Centre at Abu Mena

Pilgrimage Centre at Abu Mena.jpg.webp) Religious Complex at Abu Mena

Religious Complex at Abu Mena.jpg.webp) Ruins of the Great Basilica at Abu Mena

Ruins of the Great Basilica at Abu Mena.jpg.webp) Ruins at Abu Mena

Ruins at Abu Mena

See also

- List of ancient Egyptian towns and cities

- Church of Saint Menas (Cairo)

- Saint Fana

- Saint Mina Monastery in Mariut, the modern pilgrimage site, which borders the original Abu Mena site to the north

- World Heritage Sites in Danger

Notes

- "Abu Mena". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- Room, Adrian (2008). African placenames : origins and meanings of the names for natural features, towns, cities, provinces, and counties. Internet Archive. Jefferson, N.C. : McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-3546-3.

- Grossmann, Peter (1998). "The Pilgrimage Center of Abû Mînâ". in D. Frankfurter (ed.), Pilgrimage & Holy Space in Late Antique Egypt. Leiden-Boston-Köln, Brill: p. 282

- "Record | The Cult of Saints". csla.history.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2023-08-12.

- Talbot, Alice-Mary (2002). "Pilgrimage to Healing Shrines: The Evidence of Miracle Accounts". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. 56: 153–173. doi:10.2307/1291860. JSTOR 1291860.

- Armstrong, Gregory T. (1967). "Constantine's Churches". Gesta. International Center of Medieval Art. 6: 1–9. doi:10.2307/766661. JSTOR 766661. S2CID 191762441.

- Anderson, William. An Archaeology of Late Antique Pilgrim Flasks, Anatolian Studies, Vol. 54, (2004), pp. 79–93, British Institute at Ankara.

- Bagnall, Roger S. (2001). "Archaeological Work on Hellenistic and Roman Egypt, 1995–2000". American Journal of Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 105 (2): 227–243. doi:10.2307/507272. JSTOR 507272. S2CID 194049544.

- Weitzmann, Kurt (1977). "The Late Roman World". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 35 (2): 2–96. doi:10.2307/3259887. JSTOR 3259887.

- Wilber, Donald N. (1940). "The Coptic Frescoes of Saint Menas at Medinet Habu". The Art Bulletin. College Art Association. 22 (2): 86–103. doi:10.2307/3046689. JSTOR 3046689.

- "Abu Mena: Indicators". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2017-09-17.

- "Abu Mena (Threats to the Site 2001)". UNESCO. UNESCO. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- Ramadan, Ragab. "Funding issues threaten preservation of Christian sanctuary". Egypt Independent. Al-Masry Al-Youm. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- "Abu Mena(Egypt)". UNESCO. UNESCO. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- "Smart Sustainable Membrane for Historical Sites Conservation, Case Study: Abu Mena, Alexandria". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2018-12-08.

Further reading

- O'Brien, Harriet (June 18, 2006). "The World's Most Remarkable Buildings Under Threat". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2012-11-04.

- ICOMOS Heritage at Risk 2001/2002

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 591, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790

External links

- Abu Mena at UNESCO World Heritage Centre; includes links to 360˚ panoramic photos of the site