Metacentric height

The metacentric height (GM) is a measurement of the initial static stability of a floating body. It is calculated as the distance between the centre of gravity of a ship and its metacentre. A larger metacentric height implies greater initial stability against overturning. The metacentric height also influences the natural period of rolling of a hull, with very large metacentric heights being associated with shorter periods of roll which are uncomfortable for passengers. Hence, a sufficiently, but not excessively, high metacentric height is considered ideal for passenger ships.

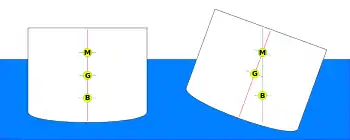

As long as the load of a ship remains stable, G is fixed (relative to the ship). For small angles, M can also be considered to be fixed, while B moves as the ship heels.

Metacentre

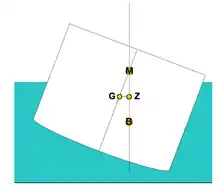

When a ship heels (rolls sideways), the centre of buoyancy of the ship moves laterally. It might also move up or down with respect to the water line. The point at which a vertical line through the heeled centre of buoyancy crosses the line through the original, vertical centre of buoyancy is the metacentre. The metacentre remains directly above the centre of buoyancy by definition.

In the diagram above, the two Bs show the centres of buoyancy of a ship in the upright and heeled conditions. The metacentre, M, is considered to be fixed relative to the ship for small angles of heel; however, at larger angles the metacentre can no longer be considered fixed, and its actual location must be found to calculate the ship's stability.

It can be calculated using the formulae:

Where KB is the centre of buoyancy (height above the keel), I is the second moment of area of the waterplane around the rotation axis in metres4, and V is the volume of displacement in metres3. KM is the distance from the keel to the metacentre.[1]

Stable floating objects have a natural rolling frequency, just like a weight on a spring, where the frequency is increased as the spring gets stiffer. In a boat, the equivalent of the spring stiffness is the distance called "GM" or "metacentric height", being the distance between two points: "G" the centre of gravity of the boat and "M", which is a point called the metacentre.

Metacentre is determined by the ratio between the inertia resistance of the boat and the volume of the boat. (The inertia resistance is a quantified description of how the waterline width of the boat resists overturning.) Wide and shallow or narrow and deep hulls have high transverse metacenters (relative to the keel), and the opposite have low metacenters . Ignoring the ballast, wide and shallow or narrow and deep means that the ship is very quick to roll and very hard to overturn and is stiff.

"G", is the center of gravity. "GM", the stiffness parameter of a boat, can be lengthened by lowering the center of gravity or changing the hull form (and thus changing the volume displaced and second moment of area of the waterplane) or both.

An ideal boat strikes a balance. Very tender boats with very slow roll periods are at risk of overturning, but are comfortable for passengers. However, vessels with a higher metacentric height are "excessively stable" with a short roll period resulting in high accelerations at the deck level.

Sailing yachts, especially racing yachts, are designed to be stiff, meaning the distance between the centre of mass and the metacentre is very large in order to resist the heeling effect of the wind on the sails. In such vessels, the rolling motion is not uncomfortable because of the moment of inertia of the tall mast and the aerodynamic damping of the sails.

Different centres

The centre of buoyancy is at the centre of mass of the volume of water that the hull displaces. This point is referred to as B in naval architecture. The centre of gravity of the ship is commonly denoted as point G or CG. When a ship is at equilibrium, the centre of buoyancy is vertically in line with the centre of gravity of the ship.[2]

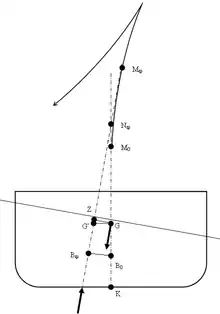

The metacentre is the point where the lines intersect (at angle φ) of the upward force of buoyancy of φ ± dφ. When the ship is vertical, the metacentre lies above the centre of gravity and so moves in the opposite direction of heel as the ship rolls. This distance is also abbreviated as GM. As the ship heels over, the centre of gravity generally remains fixed with respect to the ship because it just depends on the position of the ship's weight and cargo, but the surface area increases, increasing BMφ. Work must be done to roll a stable hull. This is converted to potential energy by raising the centre of mass of the hull with respect to the water level or by lowering the centre of buoyancy or both. This potential energy will be released in order to right the hull and the stable attitude will be where it has the least magnitude. It is the interplay of potential and kinetic energy that results in the ship having a natural rolling frequency. For small angles, the metacentre, Mφ, moves with a lateral component so it is no longer directly over the centre of mass.[3]

The righting couple on the ship is proportional to the horizontal distance between two equal forces. These are gravity acting downwards at the centre of mass and the same magnitude force acting upwards through the centre of buoyancy, and through the metacentre above it. The righting couple is proportional to the metacentric height multiplied by the sine of the angle of heel, hence the importance of metacentric height to stability. As the hull rights, work is done either by its centre of mass falling, or by water falling to accommodate a rising centre of buoyancy, or both.

For example, when a perfectly cylindrical hull rolls, the centre of buoyancy stays on the axis of the cylinder at the same depth. However, if the centre of mass is below the axis, it will move to one side and rise, creating potential energy. Conversely if a hull having a perfectly rectangular cross section has its centre of mass at the water line, the centre of mass stays at the same height, but the centre of buoyancy goes down as the hull heels, again storing potential energy.

When setting a common reference for the centres, the molded (within the plate or planking) line of the keel (K) is generally chosen; thus, the reference heights are:

- KB – to Centre of Buoyancy

- KG – to Centre of Gravity

- KMT – to Transverse Metacentre

Righting arm

The metacentric height is an approximation for the vessel stability at a small angle (0-15 degrees) of heel. Beyond that range, the stability of the vessel is dominated by what is known as a righting moment. Depending on the geometry of the hull, naval architects must iteratively calculate the center of buoyancy at increasing angles of heel. They then calculate the righting moment at this angle, which is determined using the equation:

Where RM is the righting moment, GZ is the righting arm and Δ is the displacement. Because the vessel displacement is constant, common practice is to simply graph the righting arm vs the angle of heel. The righting arm (known also as GZ — see diagram): the horizontal distance between the lines of buoyancy and gravity.[3]

- [2] at small angles of heel

There are several important factors that must be determined with regards to righting arm/moment. These are known as the maximum righting arm/moment, the point of deck immersion, the downflooding angle, and the point of vanishing stability. The maximum righting moment is the maximum moment that could be applied to the vessel without causing it to capsize. The point of deck immersion is the angle at which the main deck will first encounter the sea. Similarly, the downflooding angle is the angle at which water will be able to flood deeper into the vessel. Finally, the point of vanishing stability is a point of unstable equilibrium. Any heel lesser than this angle will allow the vessel to right itself, while any heel greater than this angle will cause a negative righting moment (or heeling moment) and force the vessel to continue to roll over. When a vessel reaches a heel equal to its point of vanishing stability, any external force will cause the vessel to capsize.

Sailing vessels are designed to operate with a higher degree of heel than motorized vessels and the righting moment at extreme angles is of high importance.

Monohulled sailing vessels should be designed to have a positive righting arm (the limit of positive stability) to at least 120° of heel,[4] although many sailing yachts have stability limits down to 90° (mast parallel to the water surface). As the displacement of the hull at any particular degree of list is not proportional, calculations can be difficult, and the concept was not introduced formally into naval architecture until about 1970.[5]

Stability

GM and rolling period

The metacentre has a direct relationship with a ship's rolling period. A ship with a small GM will be "tender" - have a long roll period. An excessively low or negative GM increases the risk of a ship capsizing in rough weather, for example HMS Captain or the Vasa. It also puts the vessel at risk of potential for large angles of heel if the cargo or ballast shifts, such as with the Cougar Ace. A ship with low GM is less safe if damaged and partially flooded because the lower metacentric height leaves less safety margin. For this reason, maritime regulatory agencies such as the International Maritime Organization specify minimum safety margins for seagoing vessels. A larger metacentric height on the other hand can cause a vessel to be too "stiff"; excessive stability is uncomfortable for passengers and crew. This is because the stiff vessel quickly responds to the sea as it attempts to assume the slope of the wave. An overly stiff vessel rolls with a short period and high amplitude which results in high angular acceleration. This increases the risk of damage to the ship and to cargo and may cause excessive roll in special circumstances where eigenperiod of wave coincide with eigenperiod of ship roll. Roll damping by bilge keels of sufficient size will reduce the hazard. Criteria for this dynamic stability effect remain to be developed. In contrast, a "tender" ship lags behind the motion of the waves and tends to roll at lesser amplitudes. A passenger ship will typically have a long rolling period for comfort, perhaps 12 seconds while a tanker or freighter might have a rolling period of 6 to 8 seconds.

The period of roll can be estimated from the following equation:[2]

where g is the gravitational acceleration, a44 is the added radius of gyration and k is the radius of gyration about the longitudinal axis through the centre of gravity and is the stability index.

Damaged stability

If a ship floods, the loss of stability is caused by the increase in KB, the centre of buoyancy, and the loss of waterplane area - thus a loss of the waterplane moment of inertia - which decreases the metacentric height.[2] This additional mass will also reduce freeboard (distance from water to the deck) and the ship's downflooding angle (minimum angle of heel at which water will be able to flow into the hull). The range of positive stability will be reduced to the angle of down flooding resulting in a reduced righting lever. When the vessel is inclined, the fluid in the flooded volume will move to the lower side, shifting its centre of gravity toward the list, further extending the heeling force. This is known as the free surface effect.

Free surface effect

In tanks or spaces that are partially filled with a fluid or semi-fluid (fish, ice, or grain for example) as the tank is inclined the surface of the liquid, or semi-fluid, stays level. This results in a displacement of the centre of gravity of the tank or space relative to the overall centre of gravity. The effect is similar to that of carrying a large flat tray of water. When an edge is tipped, the water rushes to that side, which exacerbates the tip even further.

The significance of this effect is proportional to the cube of the width of the tank or compartment, so two baffles separating the area into thirds will reduce the displacement of the centre of gravity of the fluid by a factor of 9. This is of significance in ship fuel tanks or ballast tanks, tanker cargo tanks, and in flooded or partially flooded compartments of damaged ships. Another worrying feature of free surface effect is that a positive feedback loop can be established, in which the period of the roll is equal or almost equal to the period of the motion of the centre of gravity in the fluid, resulting in each roll increasing in magnitude until the loop is broken or the ship capsizes.

This has been significant in historic capsizes, most notably the MS Herald of Free Enterprise and the MS Estonia.

Transverse and longitudinal metacentric heights

There is also a similar consideration in the movement of the metacentre forward and aft as a ship pitches. Metacentres are usually separately calculated for transverse (side to side) rolling motion and for lengthwise longitudinal pitching motion. These are variously known as and , GM(t) and GM(l), or sometimes GMt and GMl .

Technically, there are different metacentric heights for any combination of pitch and roll motion, depending on the moment of inertia of the waterplane area of the ship around the axis of rotation under consideration, but they are normally only calculated and stated as specific values for the limiting pure pitch and roll motion.

Measurement

The metacentric height is normally estimated during the design of a ship but can be determined by an inclining test once it has been built. This can also be done when a ship or offshore floating platform is in service. It can be calculated by theoretical formulas based on the shape of the structure.

The angle(s) obtained during the inclining experiment are directly related to GM. By means of the inclining experiment, the 'as-built' centre of gravity can be found; obtaining GM and KM by experiment measurement (by means of pendulum swing measurements and draft readings), the centre of gravity KG can be found. So KM and GM become the known variables during inclining and KG is the wanted calculated variable (KG = KM-GM)

References

- Ship Stability. Kemp & Young. ISBN 0-85309-042-4

- Comstock, John (1967). Principles of Naval Architecture. New York: Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers. p. 827. ISBN 9997462556.

- Harland, John (1984). Seamanship in the age of sail. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 43. ISBN 0-85177-179-3.

- Rousmaniere, John, ed. (1987). Desirable and Undesirable Characteristics of Offshore Yachts. New York, London: W.W.Norton. pp. 310. ISBN 0-393-03311-2.

- U.S. Coast Guard Technical computer program support accessed 20 December 2006.