Methoni, Messenia

Methoni (Greek: Μεθώνη, Italian: Modone, Venetian: Modon) is a village and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality of Pylos-Nestor, of which it is a municipal unit.[2] The municipal unit has an area of 97.202 km2.[3] Its name may be derived from Mothona, a mythical rock. It is located 11 km south of Pylos and 11 km west of Foinikounta. The municipal unit of Methoni includes the nearby villages of Grizokampos, Finikouda, Foiniki, Lachanada, Varakes, Kainourgio Chorio, Kamaria, Evangelismos, and the Oinnoussai Islands. The islands are Sapientza, Schiza, and Santa Marina; they form a natural protection for Methoni harbour. The town is also known by the Italian name Modone, which it was called by the Venetians.

Methoni

Μεθώνη | |

|---|---|

| |

Methoni Location within the regional unit  | |

| Coordinates: 36°49′18″N 21°42′25″E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Peloponnese |

| Regional unit | Messenia |

| Municipality | Pylos-Nestor |

| • Municipal unit | 97.202 km2 (37.530 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipal unit | 2,598 |

| • Municipal unit density | 27/km2 (69/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

Its economy is dominated by tourism, attracted by its beaches (including Tapia, Kokkinia and Kritika) and its historical castle.

Subdivisions

The municipal unit of Methoni is subdivided into the following communities (constituent villages in brackets):

- Methoni (Methoni, Kokkinia, Kritika, Sapientza (island), Tapia)

- Evangelismos (Evangelismos, Dentroulia, Kamaria)

- Foiniki

- Foinikounta (Foinikounta, Anemomylos, Chounakia, Grizokampos, Loutsa, Schiza (island))

- Kainourgio Chorio (Kainourgio Chorio, Varakes)

- Lachanada (Lachanada, Nerantzies)

Historical population

| Year | Town population | Municipality population |

|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 1,173 | 2,666 |

| 2001 | 1,169 | 2,638 |

| 2011 | 1,209 | 2,598 |

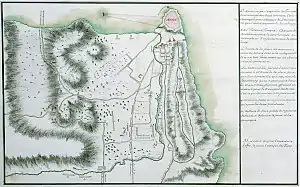

History

Antiquity and Byzantine era

Methoni has been identified as the city of Pedasus, which Homer mentions under the name "ampeloessa" (of vine leaves), as the last of the seven εὐναιόμενα πτολίεθρα (eunaiomena ptoliethra) (well-peopled cities) that Agamemnon offers Achilles in order to subdue his rage. Pausanias knew the city as Mothone, named either after the daughter of Oeneus or after the rock Mothon, which protects the harbour, and mentioned a temple to Athena Anemotis there.[4] The Oinoussai complex of islands protected the port of Methoni from the turbulent sea. Along with the rest of Messenia, the town gained its independence from the Spartans in 369 BC.

Like other Mediterranean coastal settlements, Methoni was probably heavily affected by the tsunami that followed the earthquake in AD 365. Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus wrote that as a result of the earthquake some ships had been "hurled nearly two miles from the shore", giving as an example a Laconian vessel that was stranded "near the town of Methone".[5]

During the Byzantine years Methoni retained its remarkable harbor and remained one of the most important cities of the Peloponnese, seat of a bishopric.

First Venetian era

The Republic of Venice had its eye on Methoni (Modon) since the 12th century, due to its location on the route from Venice to the Eastern markets. In 1125, they launched an attack against pirates based at Methoni, who had captured some Venetian traders on their way home from the east.

In the mid-12th century, the Muslim traveller and geographer al-Idrisi mentioned Methoni as a fortified town with a citadel.[6]

At the time of the fall of Constantinople to the Fourth Crusade, one of the Crusaders, Geoffrey of Villehardouin, was shipwrecked near Methoni, and he spent the winter of 1204/5 there. He came into contact with a local Greek magnate—identified by some scholars with a certain John Kantakouzenos—and aided him in subduing much of the region. Villehardouin's sojourn there was brief, however, since the Greek magnate died, and his son and successor turned against Villehardouin, who was forced to flee Messenia, and made for the Argolid, where a Crusader army under Boniface of Montferrat had arrived.[7] From there, Villehardouin and another Crusader, William of Champlitte, led the conquest of the Peloponnese from the local Greeks and the establishment of a Crusader principality, the Principality of Achaea.[8] In the treaty of partition of the Byzantine Empire by the Crusaders, the Partitio Romaniae, most of the peninsula had been assigned to the Republic of Venice in the treaty of partition, but the Venetians did not take action to pre-empt or hinder Champlitte and Villehardouin. It was not until 1206 or 1207 that a Venetian fleet under Premarini and the son of the Doge Enrico Dandolo arrived in the Peloponnese, and captured Methoni, along with Koroni. Venice and the Principality of Achaea quickly came to terms, recognizing each other's possessions in the Treaty of Sapienza (1209).[9][10]

Koroni was fortified, but Methoni was, for the time being, left without walls.[11] Roman Catholic bishops were installed in the two local dioceses, who were both suffragans of the Latin Archbishopric of Patras; and in 1212 the Pope placed the Latin Bishopric of Modon under his personal protection.[12] Under Venetian rule, the town experienced its zenith, becoming an important center for trade with the Levant and enjoying great prosperity. Methoni became an important staging point on the route between Venice and the Holy Lands, and many descriptions of it survive in pilgrims' accounts.[6]

Ottoman era

With the Ottoman conquest of the Despotate of the Morea, the town came under threat; Christian and Jewish refugees from the rest of the Peloponnese flocked to its walls, while the Turks raided its environs. In 1499–1500, Ottoman ships raided the town from the sea, while Sultan Bayezid II in person arrived to supervise its siege. After 28 days, on 9 August 1500, Methoni fell. The populace was either massacred or sold off as slaves.[6] In 1532, the Knights Hospitaller briefly recaptured the fortress and left with reportedly 1,600 Muslim prisoners.[6]

Then Sultan Bayezid came inside; he entered and prayed in the Frankish church which he converted into a mosque, as it remains to the present day. [Other churches were burned.] They butchered the pitiable Christians. They say that the slaughter was so great that blood ran into the sea and stained it red. From there, after Bayezid had prayed, he… ordered all Methonians captured alive, young and old, to be brought before him. He ordered the execution of all those who were ten years or older; and so it happened. They gathered their heads and bodies, put them together, and built a big tower outside the city, which can still be seen nowadays. This happened in 1499.

The Venetians returned under Francesco Morosini in 1686 during the Morean War. A Venetian census shortly afterwards lists Methoni with only 236 inhabitants, indicative of the general depopulation of the region during that time.[6] The second period of Venetian rule lasted until 1715, when the Grand Vizier Damad Ali Pasha invaded the Peloponnese. Although strengthened by the garrisons of Navarino and Koroni, who fled their fortresses, Methoni surrendered quickly once the Ottoman army arrived and began to besiege it. Nevertheless, the Grand Vizier ordered his troops to kill all Christians in the town, and as a result many chose to convert on the spot to Islam to save themselves.[6]

Following the Ottoman recapture of the town, the pre-1684 owners were allowed to claim their former property. A period of recovery followed, particularly after 1725, when the town once more became a hub of trade with the Ottoman provinces of North Africa.[6] In 1770, during the Russian-sponsored Orlov Revolt, the castle was besieged for a long time by the Russians under Prince Yuri Vladimirovich Dolgorukov. Unable to storm the castle, the siege was dominated by artillery duels until Turks and Albanians from the interior of the Peloponnese came to the aid of the garrison and drove away the Russians after a fierce battle in May 1770. The Russians suffered heavy casualties, and were forced to abandon most of their guns. They fled to their base in Navarino, which they also abandoned soon afterwards.[6]

Greek War of Independence

By the time of the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in 1821, the town was inhabited by Turks, some 400 to 500 fighting men, who also owned most of the land in the area. Outside the walls, the region was populated almost exclusively by Greeks.[6] When the Greek revolution broke out, Methoni was put under siege, along with Koroni and Navarino. In July 1821, the Ottoman fleet succeeded in reprovisioning the town, but not Navarino, which on 8 August capitulated to the Greeks. The garrison of Methoni had set out to aid them, but were stopped by the Greek rebels en route. Thereafter, the Greek pressure on Methoni slackened, and the town remained in Ottoman hands throughout the conflict, albeit only thanks to frequent reprovisioning by the fleet.[6] Consequently, the town was one of the main bases for Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt's expedition against the Greeks in 1825–28. The fortress surrendered to the French Morea Expedition on 8 October 1828, and in 1833 the departing French turned over its control to the newly established Kingdom of Greece.[6]

Methoni in art and literature

One of the possible interpretations of Vittore Carpaccio's Young Knight in a Landscape identifies the knight as the Venetian patrician Marco Gabriel, who was rector (governor) of Methoni during the Ottoman siege of 1500. His family would have commissioned the painting as a tribute to his memory. Being the only Venetian survivor of the siege, he had been accused of cowardice; taken by the Ottomans to Constantinople, he was beheaded there on 4 November 1501.[14]

About seventy years later, after the Battle of Lepanto (7 October 1571), Miguel de Cervantes was taken to Methoni as a prisoner and spent some time in the Turkish tower. He might have conceived a few pages of the Don Quixote while there.[15]

On 10 August 1806, François-René de Chateaubriand disembarked at Methoni and started his Grand Tour across Greece and the Middle East, an account of which he published in 1811 as the Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem (Itinerary from Paris to Jerusalem).[15]

Climate

Methoni has a hot-summer mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa). Precipitations falls mainly in the winter, with relatively little rain in the summer. Methoni experiences mild winters and hot, dry summers. The average annual temperature is 19.0 °C or 66.2 °F. About 681 mm or 26.8 inches of precipitation falls annually.[16]

Transportation

Methoni is the southern terminus of the Greek National Road 9 (Patras - Kyparissia - Methoni). Another road links Methoni with Koroni to its east.

References

- "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- "ΦΕΚ B 1292/2010, Kallikratis reform municipalities" (in Greek). Government Gazette.

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-21.

- Pausanias Description of Greece 4.35

- Kelly 2004, p. 141, "For the mass of waters returning when least expected killed many thousands by drowning, and with the tides whipped up to a height as they rushed back, some ships, after the anger of the watery element had grown old, were seen to have sunk, and the bodies of people killed in shipwrecks lay there, faces up or down. Other huge ships, thrust out by the mad blasts, perched on the roofs of houses, as happened at Alexandria, and others were hurled nearly two miles from the shore, like the Laconian vessel near the town of Methone which I saw when I passed by, yawning apart from long decay."

- Bees 1993, p. 217.

- Bon 1969, p. 57.

- Bon 1969, pp. 57ff..

- Setton 1976, pp. 24–26, 34.

- Bon 1969, p. 66.

- Bon 1969, p. 67.

- Bon 1969, pp. 92–93, 99.

- Sword and Scimitar: Fourteen Centuries of War between Islam and the West. Hachette Books. 28 August 2018. ISBN 9780306825569.

- "Fabio Isman reports on scholar Augusto Gentili's identification of sitter of portrait "Young Knight in Landscape" at the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza".

- Alexander Eliot. The Penguin Guide to Greece. London, 1991

- "Methoni climate: Average Temperature, weather by month, Methoni water temperature - Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 2023-03-19.

Sources

- Bees, Nikos A. (1993). "Modon". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume VII: Mif–Naz (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 216–218. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Bon, Antoine (1969). La Morée franque. Recherches historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur la principauté d'Achaïe [The Frankish Morea. Historical, Topographic and Archaeological Studies on the Principality of Achaea] (in French). Paris: De Boccard. OCLC 869621129.

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1976). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume I: The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-114-0.

External links

- Information on the municipality of Methoni from the Greek Ministry of Interior Archived 2003-10-27 at the Wayback Machine (in Greek)