Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico (Spanish: Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean,[2] mostly surrounded by the North American continent.[3] It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southwest and south by the Mexican states of Tamaulipas, Veracruz, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatán, and Quintana Roo; and on the southeast by Cuba. The Southern U.S. states of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida, which border the Gulf on the north, are often referred to as the "Third Coast" of the United States (in addition to its Atlantic and Pacific coasts).

| Gulf of Mexico | |

|---|---|

Gulf of Mexico coastline near Galveston, Texas | |

Bathymetry of the Gulf of Mexico | |

| Location | American Mediterranean Sea |

| Coordinates | 25°N 90°W |

| River sources | Rio Grande, Mississippi River, Mobile River, Panuco River, Jamapa River, Pascagoula River, Tecolutla River, Usumacinta River, Apalachicola river |

| Ocean/sea sources | Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea |

| Basin countries | List |

| Max. width | 1,500 km (932.06 mi) |

| Surface area | 1,550,000 km2 (600,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 1,615 metres (5,299 ft)[1] |

| Max. depth | 3,750 to 4,384 metres (12,303 to 14,383 ft)[1] |

| Settlements | Veracruz, Houston, New Orleans, Corpus Christi, Tampa, Havana, Southwest Florida, Mobile, Gulfport, Tampico, Key West, Cancún, Ciudad del Carmen, Coatzacoalcos, Panama City |

The Gulf of Mexico took shape approximately 300 million years ago as a result of plate tectonics.[4] The Gulf of Mexico basin is roughly oval in shape and is approximately 810 nautical miles (1,500 km; 930 mi) wide. Its floor consists of sedimentary rocks and recent sediments. It is connected to part of the Atlantic Ocean through the Florida Straits between the U.S. and Cuba, and with the Caribbean Sea via the Yucatán Channel between Mexico and Cuba. Because of its narrow connection to the Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf experiences very small tidal ranges. The size of the Gulf basin is approximately 1.6 million km2 (615,000 sq mi). Almost half of the basin consists of shallow continental-shelf waters. The volume of water in the basin is roughly 2.4×106 cubic kilometers (5.8×105 cubic miles).[5] The Gulf of Mexico is one of the most important offshore petroleum production regions in the world, making up one-sixth of the United States' total production.[6]

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the southeast limit of the Gulf of Mexico as:[7]

A line joining Cape Catoche Light (21°37′N 87°04′W) with the Light on Cape San Antonio in Cuba, through this island to the meridian of 83°W and to the Northward along this meridian to the latitude of the South point of the Dry Tortugas (24°35'N), along this parallel Eastward to Rebecca Shoal (82°35'W) thence through the shoals and Florida Keys to the mainland at the eastern end of Florida Bay and all the narrow waters between the Dry Tortugas and the mainland being considered to be within the Gulf.

Geology

The consensus among geologists[4][8][9] who have studied the geology of the Gulf of Mexico is that before the Late Triassic, the Gulf of Mexico did not exist. Before the Late Triassic, the area now occupied by the Gulf of Mexico consisted of dry land, which included continental crust that now underlies Yucatán, within the middle of the large supercontinent of Pangea. This land lay south of a continuous mountain range that extended from north-central Mexico, through the Marathon Uplift in West Texas and the Ouachita Mountains of Oklahoma, and to Alabama where it linked directly to the Appalachian Mountains. It was created by the collision of continental plates that formed Pangea. As interpreted by Roy Van Arsdale and Randel T. Cox, this mountain range was breached in Late Cretaceous times by the formation of the Mississippi Embayment.[10][11]

Geologists and other Earth scientists agree in general that the present Gulf of Mexico basin originated in Late Triassic time as the result of rifting within Pangea.[12] The rifting was associated with zones of weakness within Pangea, including sutures where the Laurentia, South American, and African plates collided to create it. First, there was a Late Triassic-Early Jurassic phase of rifting during which rift valleys formed and filled with continental red beds. Second, as rifting progressed through Early and Middle Jurassic times, the continental crust was stretched and thinned. This thinning created a broad zone of transitional crust, which displays modest and uneven thinning with block faulting, and a broad zone of uniformly thinned transitional crust, which is half the typical 40-kilometer (25 mi) thickness of normal continental crust. It was at this time that rifting first created a connection to the Pacific Ocean across central Mexico and later eastward to the Atlantic Ocean. This flooded the opening basin to create the Gulf of Mexico as an enclosed marginal sea. While the Gulf of Mexico was a restricted basin, the subsiding transitional crust was blanketed by the widespread deposition of Louann Salt and associated anhydrite evaporites. During the Late Jurassic, continued rifting widened the Gulf of Mexico and progressed to the point that sea-floor spreading and formation of oceanic crust occurred. At this point, sufficient circulation with the Atlantic Ocean was established that the deposition of Louann Salt ceased.[8][9][13][14] Seafloor spreading stopped at the end of Jurassic time, about 145–150 million years ago.

During the Late Jurassic through Early Cretaceous, the basin occupied by the Gulf of Mexico experienced a period of cooling and subsidence of the crust underlying it. The subsidence was the result of a combination of crustal stretching, cooling, and loading. Initially, the combination of crustal stretching and cooling caused about 5–7 km (3.1–4.3 mi) of tectonic subsidence of the central thin transitional and oceanic crust. Because subsidence occurred faster than sediment could fill it, the Gulf of Mexico expanded and deepened.[8][14][15]

Later, loading of the crust within the Gulf of Mexico and adjacent coastal plain by the accumulation of kilometers of sediments during the rest of the Mesozoic and all of the Cenozoic further depressed the underlying crust to its current position about 10–20 km (6.2–12.4 mi) below sea level. Particularly during the Cenozoic, a time of relative stability for the Gulf's coastal zones,[16] thick clastic wedges built out the continental shelf along the northwestern and northern margins of the Gulf of Mexico.[8][14][15]

To the east, the stable Florida platform was not covered by the sea until the latest Jurassic or the beginning of Cretaceous time. The Yucatán platform was emergent until the mid-Cretaceous. After both platforms were submerged, the formation of carbonates and evaporites has characterized the geologic history of these two stable areas. Most of the basin was rimmed during the Early Cretaceous by carbonate platforms, and its western flank was involved during the latest Cretaceous and early Paleogene periods in a compressive deformation episode, the Laramide Orogeny, which created the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico.[17]

In 2014 Erik Cordes of Temple University and others discovered a brine pool 3,300 feet (1,000 m) below the gulf's surface, with a circumference of 100 feet (30 m) and 12 feet (3.7 m) feet deep, which is four to five times saltier than the rest of the water. The first exploration of the site was unmanned, using Hercules and in 2015 a team of three used the deep submergence vehicle Alvin. The site cannot sustain any kind of life other than bacteria, mussels with a symbiotic relationship, tube worms and certain kinds of shrimp. It has been called the "Jacuzzi of Despair". Because it is warmer than the surrounding water (65 °F or 18 °C compared to 39 °F or 4 °C), animals are attracted to it, but cannot survive once they enter it.[18]

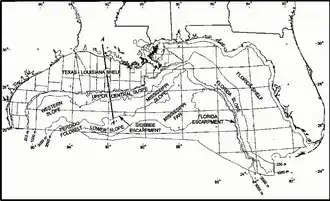

The Gulf of Mexico is 41 percent continental slope, 32 percent continental shelf, and 24 percent abyssal plain with the greatest depth of 12,467 feet in the Sigsbee Deep.[19] Seven main areas are given as:

- Gulf of Mexico basin, which contains the Sigsbee Deep and can be further divided into the continental rise, the Sigsbee Abyssal Plain, and the Mississippi Cone.

- Northeast Gulf of Mexico, which extends from a point east of the Mississippi River Delta near Biloxi to the eastern side of Apalachee Bay.

- South Florida Continental Shelf and Slope, which extends along the coast from Apalachee Bay to the Straits of Florida and includes the Florida Keys and Dry Tortugas

- Campeche Bank, which extends from the Yucatán Straits in the east to the Tabasco–Campeche Basin in the west and includes Arrecife Alacran.

- Bay of Campeche, which is an isthmian embayment extending from the western edge of Campeche Bank to the offshore regions just east of the port of Veracruz.

- Western Gulf of Mexico, which is located between Veracruz to the south and the Rio Grande to the north.

- Northwest Gulf of Mexico, which extends from Alabama to the Rio Grande.

History

Pre-Columbian

As early as the Maya Civilization, the Gulf of Mexico was used as a trade route off the coast of the Yucatán Peninsula and present-day Veracruz.

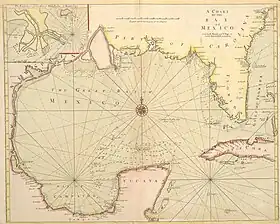

Spanish exploration

Although the Spanish voyage of Christopher Columbus was credited with the discovery of the Americas by Europeans, the ships in his four voyages never reached the Gulf of Mexico. Instead, the Spanish sailed into the Caribbean around Cuba and Hispaniola.[20] The first alleged European exploration of the Gulf of Mexico was by Amerigo Vespucci in 1497. Vespucci is purported to have followed the coastal land mass of Central America before returning to the Atlantic Ocean via the Straits of Florida between Florida and Cuba. However, this first voyage of 1497 is widely disputed and many historians doubt that it took place as described.[21] In his letters, Vespucci described this trip, and once Juan de la Cosa returned to Spain, a famous world map, depicting Cuba as an island, was produced.

In 1506, Hernán Cortés took part in the conquest of Hispaniola and Cuba, receiving a large estate of land and indigenous slaves for his effort. In 1510, he accompanied Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, an aide of the governor of Hispaniola, in his expedition to conquer Cuba. In 1518 Velázquez put him in command of an expedition to explore and secure the interior of Mexico for colonization.

In 1517, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba discovered the Yucatán Peninsula. This was the first European encounter with an advanced civilization in the Americas, with solidly built buildings and a complex social organization which they recognized as being comparable to those of the Old World; they also had reason to expect that this new land would have gold. All of this encouraged two further expeditions, the first in 1518 under the command of Juan de Grijalva, and the second in 1519 under the command of Hernán Cortés, which led to the Spanish exploration, military invasion, and ultimately settlement and colonization known as the Conquest of Mexico. Hernández did not live to see the continuation of his work: he died in 1517, the year of his expedition, as the result of the injuries and the extreme thirst suffered during the voyage, and disappointed in the knowledge that Diego Velázquez had given precedence to Grijalva as the captain of the next expedition to Yucatán.

In 1523, a treasure ship was wrecked en route along the coast of Padre Island, Texas. When word of the disaster reached Mexico City, the viceroy requested a rescue fleet and immediately sent Ángel de Villafañe, in Mexico City with Cortés, marching overland to find the treasure-laden vessels. Villafañe traveled to Pánuco and hired a ship to transport him to the site, which had already been visited from that community. He arrived in time to greet García de Escalante Alvarado (a nephew of Pedro de Alvarado), commander of the salvage operation, when Alvarado arrived by sea on July 22, 1554. The team labored until September 12 to salvage the Padre Island treasure. This loss, in combination with other ship disasters around the Gulf of Mexico, gave rise to a plan for establishing a settlement on the northern Gulf Coast to protect shipping and more quickly rescue castaways. As a result, the expedition of Tristán de Luna y Arellano was sent and landed at Pensacola Bay on August 15, 1559.

On December 11, 1526, Charles V granted Pánfilo de Narváez a license to claim what is now the Gulf Coast of the United States, known as the Narváez expedition. The contract gave him one year to gather an army, leave Spain, be large enough to found at least two towns of 100 people each, and garrison two more fortresses anywhere along the coast. On April 7, 1528, they spotted land north of what is now Tampa Bay. They turned south and traveled for two days looking for a great harbor the master pilot Miruelo knew of. Sometime during these two days, one of the five remaining ships was lost on the rugged coast, but nothing else is known of it.

In 1697, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville sailed for France and was chosen by the Minister of Marine to lead an expedition to rediscover the mouth of the Mississippi River and to colonize Louisiana which the English coveted. Iberville's fleet sailed from Brest on October 24, 1698. On January 25, 1699, Iberville reached Santa Rosa Island in front of Pensacola founded by the Spanish; he sailed from there to Mobile Bay and explored Massacre Island, later renamed Dauphin Island. He cast anchor between Cat Island and Ship Island; and on February 13, 1699, he went to the mainland, Biloxi, with his brother Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville.[22] On May 1, 1699, he completed a fort on the north-east side of the Bay of Biloxi, a little to the rear of what is now Ocean Springs, Mississippi. This fort was known as Fort Maurepas or Old Biloxi. A few days later, on May 4, Pierre Le Moyne sailed for France leaving his teenage brother, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, as second in command to the French commandant.

Geography

The Gulf of Mexico's eastern, northern, and northwestern shores lie along the US states of Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. The US portion of the Gulf coastline spans 1,680 miles (2,700 km), receiving water from 33 major rivers that drain 31 states.[26] The Gulf's southwestern and southern shores lie along the Mexican states of Tamaulipas, Veracruz, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatán, and the northernmost tip of Quintana Roo. The Mexican portion of the Gulf coastline spans 1,743 miles (2,805 km). On its southeast quadrant, the Gulf is bordered by Cuba. It supports major American, Mexican and Cuban fishing industries. The outer margins of the wide continental shelves of Yucatán and Florida receive cooler, nutrient-enriched waters from the deep by a process known as upwelling, which stimulates plankton growth in the euphotic zone. This attracts fish, shrimp, and squid.[27] River drainage and atmospheric fallout from industrial coastal cities also provide nutrients to the coastal zone.

The Gulf Stream, a warm Atlantic Ocean current and one of the strongest ocean currents known, originates in the gulf, as a continuation of the Caribbean Current-Yucatán Current-Loop Current system. Other circulation features include the anticyclonic gyres which are shed by the Loop Current and travel westward where they eventually dissipate and a permanent cyclonic gyre in the Bay of Campeche. The Bay of Campeche in Mexico constitutes a major arm of the Gulf of Mexico. Additionally, the gulf's shoreline is fringed by numerous bays and smaller inlets. A number of rivers empty into the gulf, most notably the Mississippi River and the Rio Grande in the northern gulf, and the Grijalva and Usumacinta rivers in the southern gulf. The land that forms the gulf's coast, including many long, narrow barrier islands, is almost uniformly low-lying and is characterized by marshes and swamps as well as stretches of sandy beach.

The Gulf of Mexico is an excellent example of a passive margin. The continental shelf is quite wide at most points along the coast, most notably at the Florida and Yucatán Peninsulas. The shelf is exploited for its oil by means of offshore drilling rigs, most of which are situated in the western gulf and in the Bay of Campeche. Another important commercial activity is fishing; major catches include red snapper, amberjack, tilefish, swordfish, and various grouper, as well as shrimp and crabs. Oysters are also harvested on a large scale from many of the bays and sounds. Other important industries along the coast include shipping, petrochemical processing and storage, military use, paper manufacture, and tourism.

The gulf's warm water temperature can feed powerful Atlantic hurricanes causing extensive human death and other destruction as happened with Hurricane Katrina in 2005. In the Atlantic, a hurricane will draw up cool water from the depths and making it less likely that further hurricanes will follow in its wake (warm water being one of the preconditions necessary for their formation). However, the Gulf is shallower; when a hurricane passes over the water temperature may drop but it soon rebounds and becomes capable of supporting another tropical storm.[28] From 1970 to 2020, surface temperatures warmed at approximately twice the rate observed for the global ocean surface.[29]

The Gulf is considered aseismic; however, mild tremors have been recorded throughout history (usually 5.0 or less on the Richter magnitude scale). Earthquakes may be caused by interactions between sediment loading on the sea floor and adjustment by the crust.[30]

2006 earthquake

On September 10, 2006, the U.S. Geological Survey National Earthquake Information Center reported that a magnitude 6.0 earthquake occurred about 250 miles (400 km) west-southwest of Anna Maria, Florida, around 10:56 am EDT. The quake was reportedly felt from Louisiana to Florida in the Southeastern United States. There were no reports of damage or injuries.[31][32] Items were knocked from shelves and seiches were observed in swimming pools in parts of Florida.[33] The earthquake was described by the USGS as an intraplate earthquake, the largest and most widely felt recorded in the past three decades in the region.[33] According to the September 11, 2006 issue of The Tampa Tribune, earthquake tremors were last felt in Florida in 1952, recorded in Quincy, 20 miles (32 km) northwest of Tallahassee.

Maritime boundary delimitation agreements

Cuba and Mexico: Exchange of notes constituting an agreement on the delimitation of the exclusive economic zone of Mexico in the sector adjacent to Cuban maritime areas (with map), of July 26, 1976.

Cuba and United States: Maritime boundary agreement between the United States of America and the Republic of Cuba, of December 16, 1977.

Mexico and United States: Treaty to resolve pending boundary differences and maintain the Rio Grande and Colorado River as the international boundary, of November 23, 1970; Treaty on maritime boundaries between the United States of America and the United Mexican States (Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean), of May 4, 1978, and Treaty between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the United Mexican States on the delimitation of the continental shelf in the Western Gulf of Mexico beyond 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi), of June 9, 2000.

On December 13, 2007, Mexico submitted information to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) regarding the extension of Mexico's continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles.[34] Mexico sought an extension of its continental shelf in the Western Polygon based on international law, UNCLOS, and bilateral treaties with the United States, in accordance with Mexico's domestic legislation. On March 13, 2009, the CLCS accepted Mexico's arguments for extending its continental shelf up to 350 nautical miles (650 km; 400 mi) into the Western Polygon. Since this would extend Mexico's continental shelf well into territory claimed by the United States, however, Mexico and the U.S. would need to enter a bilateral agreement based on international law that delimits their respective claims.

Shipwrecks

A ship now called the Mardi Gras sank around the early 19th century about 35 mi (56 km) off the coast of Louisiana in 4,000 feet (1,200 m) of water. She is believed to have been a privateer or trader. The shipwreck, whose real identity remains a mystery, lay forgotten at the bottom of the sea until it was discovered in 2002 by an oilfield inspection crew working for the Okeanos Gas Gathering Company (OGGC). In May 2007, an expedition, led by Texas A&M University and funded by OGGC under an agreement with the Minerals Management Service (now BOEM), was launched to undertake the deepest scientific archaeological excavation ever attempted at that time to study the site on the seafloor and recover artifacts for eventual public display in the Louisiana State Museum. As part of the project educational outreach Nautilus Productions in partnership with BOEM, Texas A&M University, the Florida Public Archaeology Network[35] and Veolia Environmental produced a one-hour HD documentary[36] about the project, short videos for public viewing and provided video updates during the expedition. Video footage from the ROV was an integral part of this outreach and used extensively in the Mystery Mardi Gras Shipwreck documentary.[37]

On July 30, 1942, the Robert E. Lee, captained by William C. Heath, was torpedoed by the German submarine U-166. She was sailing southeast of the entrance to the Mississippi River when the explosion destroyed the #3 hold, vented through the B and C decks and damaged the engines, the radio compartment and the steering gear. After the attack she was under escort by USS PC-566, captained by Lieutenant Commander Herbert G. Claudius, en route to New Orleans. PC-566 began dropping depth charges on a sonar contact, sinking U-166. The badly damaged Robert E. Lee first listed to port then to starboard and finally sank within about 15 minutes of the attack. One officer, nine crewmen and 15 passengers were lost. The passengers aboard Robert E. Lee were primarily survivors of previous torpedo attacks by German U-boats.[38] The wreck's precise location was discovered during the C & C Marine survey that located the U-166.

The German submarine U-166 was a Type IXC U-boat of Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine during World War II. The submarine was laid down on December 6, 1940, at the Seebeckwerft (part of Deutsche Schiff- und Maschinenbau AG, Deschimag) at Wesermünde (modern Bremerhaven) as yard number 705, launched on November 1, 1941, and commissioned on March 23, 1942, under the command of Oberleutnant zur See Hans-Günther Kuhlmann. After training with the 4th U-boat Flotilla, U-166 was transferred to the 10th U-boat Flotilla for front-line service on June 1, 1942. The U-boat sailed on only two war patrols and sank four ships totalling 7,593 gross register tons (GRT).[39] She was sunk on July 30, 1942, in Gulf of Mexico.[40]

In 2001 the wreck of U-166 was found in 5,000 feet (1,500 m) of water, less than two miles (3.2 km) from where it had attacked Robert E. Lee. An archaeological survey of the seafloor before the construction of a natural gas pipeline led to the discoveries by C & C Marine archaeologists Robert A. Church and Daniel J. Warren. The sonar contacts consisted of two large sections lying approximately 500 feet (150 m) apart at either end of a debris field that indicated the presence of a U-boat.[41]

Biota

Various biota include chemosynthetic communities near cold seeps and non chemosynthetic communities such as bacteria and other micro – benthos, meiofauna, macrofauna, and megafauna (larger organisms such as crabs, sea pens, crinoids, demersal fish, cetaceans, and the extinct Caribbean monk seal) are living in the Gulf of Mexico.[42] Recently, resident Bryde's whales within the gulf were classified as an endemic, unique subspecies and making them as one of the most endangered whales in the world.[43] The Gulf of Mexico yields more finfish, shrimp, and shellfish annually than the south and mid-Atlantic, Chesapeake, and New England areas combined.[5]

The Smithsonian Institution Gulf of Mexico holdings are expected to provide an important baseline of understanding for future scientific studies on the impact of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.[44] In Congressional testimony, Dr. Jonathan Coddington, associate director of Research and Collections at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, provides a detailed overview of the Gulf collections and their sources which Museum staff have made available on an online map. The samples were collected for years by the former Minerals Management Service (renamed the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement) to help predict the potential impacts of future oil/gas explorations. Since 1979, the specimens have been deposited in the national collections of the National Museum of Natural History.[45]

Pollution

The major environmental threats to the Gulf are agricultural runoff and oil drilling.

There are frequent "red tide" algae blooms[46] that kill fish and marine mammals and cause respiratory problems in humans and some domestic animals when the blooms reach close to shore. This has especially been plaguing the southwest and southern Florida coast, from the Florida Keys to north of Pasco County, Florida.

In 1973 the United States Environmental Protection Agency prohibited the dumping of undiluted chemical waste by manufacturing interests into the Gulf and the military confessed to similar behavior in waters off Horn Island.[47]

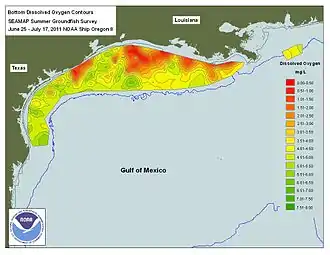

The Gulf contains a hypoxic dead zone that runs east–west along the Texas-Louisiana coastline. In July 2008, researchers reported that between 1985 and 2008, the area roughly doubled in size.[48] It was 8,776 square miles (22,730 km2) in 2017, the largest ever recorded.[49] Poor agricultural practices in the northern portion of the Gulf of Mexico have led to a tremendous increase of nitrogen and phosphorus in neighboring marine ecosystems, which has resulted in algae blooms and a lack of available oxygen. Occurrences of masculinization and estrogen suppression were observed as a result. An October 2007 study of the Atlantic croaker found a disproportioned sex ratio of 61% males to 39% females in hypoxic Gulf sites. This was compared with a 52% to 48% male-female ratio found in reference sites, showing an impairment of reproductive output for fish populations inhabiting hypoxic coastal zones.[50]

Microplastics within semi-enclosed seas like the Gulf have been reported in high concentrations and the Gulf's first such study estimated concentrations that rival the highest globally reported.[51]

There are 27,000 abandoned oil and gas wells beneath the Gulf. These have generally not been checked for potential environmental problems.[52]

Ixtoc I explosion and oil spill

In June 1979, the Ixtoc I oil platform in the Bay of Campeche suffered a blowout leading to a catastrophic explosion, which resulted in a massive oil spill that continued for nine months before the well was finally capped. This was ranked as the largest oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico until the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010.

Deepwater Horizon explosion and oil spill

On April 20, 2010, the Deepwater Horizon oil platform, located in the Mississippi Canyon about 40 miles (64 km) off the Louisiana coast, suffered a catastrophic explosion; it sank a day and a half later.[53] It was in the process of being sealed with cement for temporary abandonment, to avoid environmental problems.[52] Although initial reports indicated that relatively little oil had leaked, by April 24, it was claimed by BP that approximately 1,000 barrels (160 m3) of oil per day were issuing from the wellhead, about 1-mile (1.6 km) below the surface on the ocean floor.[54] On April 29, the U.S. government revealed that approximately 5,000 barrels (790 m3) per day, five times the original estimate, were pouring into the Gulf from the wellhead.[55] The resulting oil slick quickly expanded to cover hundreds of square miles of ocean surface, posing a serious threat to marine life and adjacent coastal wetlands and to the livelihoods of Gulf Coast shrimpers and fishermen.[56] Coast Guard Rear Adm. Sally Brice O'Hare stated that the US government will be "employing booms, skimmers, chemical dispersants and controlled burns" to combat the oil spill. By May 1, 2010, the oil spill cleanup efforts were underway but hampered by rough seas and the "tea like" consistency of the oil. Cleanup operations were resumed after conditions became favorable. On May 27, 2010, The USGS had revised the estimate of the leak from 5,000 barrels per day (790 m3/d) to 12,000–19,000 barrels per day (3,000 m3/d)[57] an increase from earlier estimates. On July 15, 2010, BP announced that the leak stopped for the first time in 88 days.

In July 2015 BP reached an $18.7bn settlement with the US government, the states of Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas, as well as 400 local authorities. To date, BP's cost for the clean-up, environmental and economic damages and penalties has reached $54bn.[58]

Minor oil spills

According to the National Response Center, the oil industry has thousands of minor accidents in the Gulf of Mexico every year.[59]

Brutus oil spill

On May 12, 2016, a release of oil from subsea infrastructure on Shell's Brutus oil rig released 2,100 barrels of oil. This leak created a visible 2 by 13 miles (3.2 by 20.9 km) oil slick in the sea about 97 miles (156 km) south of Port Fourchon, Louisiana, according to the U.S. Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement.[59][60]

See also

- American Mediterranean Sea

- Charlotte Harbor (estuary), an estuary in Florida

- Green Canyon, a US Gulf of Mexico petroleum exploration area

- Gulf Coast of the United States

- Gulf of Mexico Foundation

- Intra-Americas Sea

- Jack 2 (a test well in the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico)

- Keathley Canyon, a US Gulf of Mexico petroleum exploration area

- Nepheloid layer

- Orca Basin

- Outer Continental Shelf

- Sigsbee Escarpment, a US Gulf of Mexico petroleum exploration area

- Territorial evolution of the Caribbean

- Tunica Mound

References

- "General Facts about the Gulf of Mexico". GulfBase.org. Archived from the original on December 10, 2009. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

- "Gulf of Mexico – a sea in Atlantic Ocean". www.deepseawaters.com. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- "Gulf of Mexico". Geographic Names Information System. January 1, 2000. Archived from the original on December 31, 2020. Retrieved July 8, 2010.

- Huerta, A.D., and D.L. Harry (2012) Wilson cycles, tectonic inheritance, and rifting of the North American Gulf of Mexico continental margin. Geosphere. 8(1):GES00725.1, first published on March 6, 2012, doi:10.1130/GES00725.1

- "General Facts about the Gulf of Mexico". epa.gov. Archived from the original on October 3, 2006. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- "Gulf of Mexico Fact Sheet". U.S. Energy Information Administration. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2011. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- Salvador, A. (1991) Origin and development of the Gulf of Mexico basin, in A. Salvador, ed., p. 389–444, The Gulf of Mexico Basin: The Geology of North America, v. J., Geological Society of America, Boulder, Colorado.

- Stern, R.J., and W.R. Dickinson (2010) The Gulf of Mexico is a Jurassic backarc basin. Archived February 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Geosphere. 6(6):739–754.

- Van Arsdale, R. B. (2009) Adventures Through Deep Time: The Central Mississippi River Valley and Its Earthquakes. Special Paper no. 455, Geological Society of America, Boulder, Colorado. 107 pp.

- Cox, R. T., and R. B. Van Arsdale (2002) The Mississippi Embayment, North America: a first order continental structure generated by the Cretaceous superplume mantle event. Journal of Geodynamics. 34:163–176.

- Zell, P.; Stinnesbeck, W. & Beckmann, S. (2016). "Late Jurassic aptychi from the La Caja Formation of northeastern Mexico". Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana. 68 (3): 515–536. doi:10.18268/BSGM2016v68n3a8.

- Buffler, R. T., 1991, Early Evolution of the Gulf of Mexico Basin, in D. Goldthwaite, ed., pp. 1–15, Introduction to Central Gulf Coast Geology, New Orleans Geological Society, New Orleans, Louisiana.

- Galloway, W. E., 2008, Depositional evolution of the Gulf of Mexico sedimentary basin. in K.J. Hsu, ed., pp. 505–549, The Sedimentary Basins of the United States and Canada, Sedimentary Basins of the World. v. 5, Elsevier, The Netherlands.

- Sawyer, D. S., R. T. Buffler, and R. H. Pilger, Jr., 1991, The crust under the Gulf of Mexico basin, in A. Salvador, ed., pp. 53–72, The Gulf of Mexico Basin: The Geology of North America, v. J., Geological Society of America, Boulder, Colorado.

- Galloway, William E. (December 2001). "Cenozoic evolution of sediment accumulation in deltaic and shore-zone depositional systems, Northern Gulf of Mexico Basin". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 18 (10): 1031–1040. doi:10.1016/S0264-8172(01)00045-9. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- "gulfbase.org". Archived from the original on December 10, 2009.

- Niiler, Eric (May 5, 2016). "Deep-Sea Brine Lake Dubbed 'Jacuzzi of Despair'". seeker.com. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- Ward, C.H., Tunnell, J.W. (2017). Habitats and Biota of the Gulf of Mexico: An Overview. In: Ward, C. (eds) Habitats and Biota of the Gulf of Mexico: Before the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-3447-8_1. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- "Christopher Columbus - The second and third voyages". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- "Amerigo Vespucci | Biography, Accomplishments, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

- Kevin Knight (2009). "Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur d'Iberville". newadvent.org. Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- "Gulf of Mexico Watershed". EPA.gov. Archived from the original on November 6, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- National Geophysical Data Center, 1999. Global Land One-kilometer Base Elevation (GLOBE) v.1. Hastings, D. and P.K. Dunbar. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA Archived February 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. doi:10.7289/V52R3PMS [access date: March 16, 2015]

- Amante, C. and B.W. Eakins, 2009. ETOPO1 1 Arc-Minute Global Relief Model: Procedures, Data Sources and Analysis. NOAA Technical Memorandum NESDIS NGDC-24. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA Archived June 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. doi:10.7289/V5C8276M [access date: March 18, 2015].

- "National Water Program Guidance: FY 2005". epa.gov. Archived from the original on October 2, 2006. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- "Gulf of Mexico". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. June 15, 2010. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- "Warm Waters Provide Fuel for Potential Storms". NASA Earth Observatory. Archived from the original on October 1, 2006. Retrieved May 5, 2006.

- "The Gulf of Mexico Is Getting Warmer". National Centers for Environmental Information. January 30, 2023. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- "Earthquakes in the Gulf of Mexico". Archived from the original on June 29, 2007. Retrieved December 27, 2006.

- "Central Florida Feels Quake". Archived from the original on August 28, 2007. Retrieved December 27, 2006.

- "6.0 Magnitude Earthquake in Gulf of Mexico Shakes Southeast". www.observernews.net. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2006.

- United States Geological Survey, September 11, 2006 Archived October 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Heaton, S. Warren Jr. (January 2013). "Mexico's Attempt to Extend its Continental Shelf Beyond 200 Nautical Miles Serves as a Model for the International Community, Mexican Law Review, Volume V, Number 2, Jan.– June 2013" (PDF). Mexican Law Review. 1 (10). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- "FPAN Home". Florida Public Archaeology. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- "Mystery Mardi Gras Shipwreck". Nautilus Productions. Archived from the original on June 13, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- Opdyke, Mark (2007). "Mystery Mardi Gras Shipwreck Documentary". The Museum of Underwater Archaeology. Archived from the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "Robert E. Lee". German U-boats of World War II – uboat.net. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "U-166". German U-boats of World War II – uboat.net. Archived from the original on December 17, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- "Historic Shipwrecks in the Gulf of Mexico". gomr.mms.gov. Archived from the original on October 17, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- Daniel J. Warren, Robert A. Church. "The Discovery of U – 166 : Rewriting History with New Technology". Offshore Technology Conference. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 12, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- Minerals Management Service Gulf of Mexico OCS Region (November 2006). "Gulf of Mexico OCS Oil and Gas Lease Sales: 2007–2012. Western Planning Area Sales 204, 207, 210, 215, and 218. Central Planning Area Sales 205, 206, 208, 213, 216, and 222. Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Volume I: Chapters 1–8 and Appendices". U.S. Department of the Interior, Minerals Management Service, Gulf of Mexico OCS Region, New Orleans. page 3-27–3-34 PDF Archived March 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Rosel E. P.. Corkeron P.. Engleby L.. Epperson D.. Mullin D. K.. Soldevilla S. M.. Taylor L. B.. 2016. STATUS REVIEW OF BRYDE’S WHALES (BALAENOPTERA EDENI) IN THE GULF OF MEXICO UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT Archived August 7, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-692

- Zongker, Brett (July 21, 2010). "Smithsonian Holdings to Aid Researchers in the Gulf". Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 24, 2010. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- Coddington, Jonathan (June 15, 2010). "Testimony to the Subcommittee on Insular Affairs, Oceans and Wildlife; Committee on Natural Resources; U.S. House of Representatives" (PDF). [Smithsonian Ocean Portal]. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 7, 2010. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- "The Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone and Red Tides". Archived from the original on May 7, 2015. Retrieved December 27, 2006.

- Davis, Jack E. (2018). The Gulf: the Making of an American Sea. New York: Liveright Publishing Corp. p. 416. ISBN 978-1-63149-402-4.

- Joel Achenbach, "A 'Dead Zone' in The Gulf of Mexico: Scientists Say Area That Cannot Support Some Marine Life Is Near Record Size" Archived May 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post, July 31, 2008

- "New Jersey-Size 'Dead Zone' Is Largest Ever in Gulf of Mexico". National Geographic. August 2, 2017. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Thomas, Peter; Md Saydur Rahman (2012). "Extensive Reproductive Disruption, Ovarian Masculinization and Aromatase Suppression in Atlantic Croaker in the Northern Gulf of Mexico Hypoxic Zone". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1726): 28–38. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0529. PMC 3223642. PMID 21613294.

- Di Mauro, Rosana; Kupchik, Matthew J.; Benfield, Mark C. (November 2017). "Abundant plankton-sized microplastic particles in shelf waters of the northern Gulf of Mexico". Environmental Pollution. 230: 798–809. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.07.030. PMID 28734261.

- Donn, Jeff (July 7, 2010). "Gulf home to 27,000 abandoned wells". Burlington, Vermont: Burlington Free Press. pp. 1A.

- "Burning oil rig sinks, setting stage for spill; 11 still missing" Archived September 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, by Kevin McGill and Holbrook Mohr (Associated Press), Boston Globe, April 23, 2010

- "Well from sunken rig leaking oil" Archived June 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, by Cain Burdeau (Associated Press), Boston Globe, April 25, 2010

- Robertson, Campbell; Kaufman, Leslie (April 28, 2010). "Size of Spill in Gulf of Mexico Is Larger Than Thought". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- "Race to plug leaking oil well off La. spurs new tactics" Archived June 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, by Cain Burdeau (Associated Press), Boston Globe, April 27, 2010

- "Gulf Oil Spill Worst in U.S. History; Drilling Postponed" Archived January 29, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, by Marianne Lavelle, National Geographic, May 27, 2010

- Ed Crooks, Christopher Adams (July 9, 2015). "BP: Into uncharted waters". Financial Times. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- Chow, Lorraine (May 13, 2016). "Shell Oil Spill Dumps Nearly 90,000 Gallons of Crude into Gulf". EcoWatch. Archived from the original on May 20, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- Mufson, Steven. "Shell's Brutus production platform spills oil into Gulf of Mexico". Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

External links

- Resource Database for Gulf of Mexico Research

- Gulf of Mexico Integrated Science

- Mystery Mardi Gras Shipwreck

- Dickson, Henry Newton (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). p. 348.

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- Bathymetry of the Northern Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean East of Florida United States Geological Survey

- The Present State of the West-Indies: Containing an Accurate Description of What Parts Are Possessed by the Several Powers in Europe written by Thomas Kitchin, 1778, in which Kitchin discusses, in chapter 1, why the Gulf should have been called the "West Indian Sea".

- BP Oil Spill, NPR