Mikoyan MiG-29

The Mikoyan MiG-29 (Russian: Микоян МиГ-29; NATO reporting name: Fulcrum) is a twin-engine fighter aircraft designed in the Soviet Union. Developed by the Mikoyan design bureau as an air superiority fighter during the 1970s, the MiG-29, along with the larger Sukhoi Su-27, was developed to counter new U.S. fighters such as the McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle and the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon.[2] The MiG-29 entered service with the Soviet Air Forces in 1983.

| MiG-29 | |

|---|---|

_(cropped).jpg.webp) | |

| A Russian Air Force MiG-29 | |

| Role | Air superiority fighter, multirole fighter |

| National origin | Soviet Union |

| Design group | Mikoyan |

| First flight | 6 October 1977 |

| Introduction | August 1983 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Russian Aerospace Forces Indian Air Force Uzbekistan Air and Air Defence Forces Ukrainian Air Force |

| Produced | 1981–present |

| Number built | >1,600[1] |

| Variants | Mikoyan MiG-29M Mikoyan MiG-29K Mikoyan MiG-35 |

While originally oriented towards combat against any enemy aircraft, many MiG-29s have been furnished as multirole fighters capable of performing a number of different operations, and are commonly outfitted to use a range of air-to-surface armaments and precision munitions. The MiG-29 has been manufactured in several major variants, including the multirole Mikoyan MiG-29M and the navalised Mikoyan MiG-29K; the most advanced member of the family to date is the Mikoyan MiG-35. Later models frequently feature improved engines, glass cockpits with HOTAS-compatible flight controls, modern radar and infrared search and track (IRST) sensors, and considerably increased fuel capacity; some aircraft have also been equipped for aerial refueling.

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the militaries of multiple ex-Soviet republics have continued to operate the MiG-29, the largest of which is the Russian Aerospace Forces. The Russian Aerospace Forces wanted to upgrade its existing fleet to the modernised MiG-29SMT configuration, but financial difficulties have limited deliveries. The MiG-29 has also been a popular export aircraft; more than 30 nations either operate or have operated the aircraft to date.

Development

Origins

In the mid–1960s, the United States Air Force (USAF) encountered difficulties over the skies of Vietnam. Supersonic fighter bombers that had been optimized for low altitude bombing, like the F-105 Thunderchief, were found to be vulnerable to older MiG-17s and more advanced MiGs which were much more maneuverable.[3] In order to regain the limited air superiority enjoyed over Korea, the US refocused on air combat using the F-4 Phantom multirole fighter, while the Soviet Union developed the MiG-23 in response. Towards the end of the 1960s, the USAF started the "F-X" program to produce a fighter dedicated to air superiority, which led to the McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle being ordered for production in late 1969.[4]

At the height of the Cold War, a Soviet response was necessary to avoid the possibility of the Americans gaining a serious technological advantage over the Soviets, thus the development of a new air superiority fighter became a priority.[2] In 1969, the Soviet General Staff issued a requirement for a Perspektivnyy Frontovoy Istrebitel (PFI, roughly "Advanced Frontline Fighter").[5] Specifications were extremely ambitious, calling for long range, good short-field performance (including the ability to use austere runways), excellent agility, Mach 2+ speed, and heavy armament. The Russian aerodynamics institute TsAGI worked in collaboration with the Sukhoi design bureau on the aircraft's aerodynamics.[5]

By 1971, however, Soviet studies determined the need for different types of fighters. The PFI program was supplemented with the Perspektivnyy Lyogkiy Frontovoy Istrebitel (LPFI, or "Advanced Lightweight Tactical Fighter") program; the Soviet fighter force was planned to be approximately 33% PFI and 67% LPFI.[6] PFI and LPFI paralleled the USAF's decision that created the "Lightweight Fighter" program and the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon and Northrop YF-17.[7] The PFI fighter was assigned to Sukhoi, resulting in the Sukhoi Su-27, while the lightweight fighter went to Mikoyan. Detailed design work on the resultant Mikoyan Product 9, designated MiG-29A, began in 1974, with the first flight taking place on 6 October 1977. The pre-production aircraft was first spotted by United States reconnaissance satellites in November of that year; it was dubbed Ram-L because it was observed at the Zhukovsky flight test center near the town of Ramenskoye.[8][9]

The workload split between TPFI and LPFI became more apparent as the MiG-29 filtered into front line service with the Soviet Air Forces (Russian: Voenno-Vozdushnye Sily [VVS]) in the mid-1980s. While the heavy, long range Su-27 was tasked with the more exotic and dangerous role of deep air-to-air sweeps of NATO high-value assets, the smaller MiG-29 directly replaced the MiG-23 in the frontal aviation role.

Introduction and improvements

In the West, the new fighter was given the NATO reporting name "Fulcrum-A" because the pre-production MiG-29A, which should have logically received this designation, remained unknown in the West at that time. The Soviet Union did not assign official names to most of its aircraft, although nicknames were common. Unusually, some Soviet pilots found the MiG-29's NATO reporting name, "Fulcrum", to be a flattering description of the aircraft's intended purpose, and it is sometimes unofficially used in Russian service.[10]

The MiG-29B was widely exported in downgraded versions, known as MiG-29B 9-12A and MiG-29B 9-12B for Warsaw Pact and non-Warsaw Pact nations respectively, with less capable avionics and no capability for delivering nuclear weapons.

In the 1980s, Mikoyan developed the improved MiG-29S to use longer range R-27E air-to-air missiles. It added a dorsal 'hump' to the upper fuselage to house a jamming system and some additional fuel capacity. The weapons load was increased to 4,000 kg (8,800 lb) with airframe strengthening. These features were included in new-built fighters and upgrades to older MiG-29s.[11][12]

Refined versions of the MiG-29 with improved avionics were fielded by the Soviet Union, but Mikoyan's multirole variants, including a carrier-based version designated MiG-29K, were never produced in large numbers. Development of the MiG-29K carrier version was suspended for over a decade before being resumed; the type went into service with the Indian Navy's INS Vikramaditya, and Russian Navy's Admiral Kuznetsov class aircraft carrier. Mikoyan also developed improved versions MiG-29M and MiG-29SMT.[13][14]

There have been several upgrade programmes conducted for the MiG-29. Common upgrades include the adoption of standard-compatible avionics, service life extensions to 4,000 flight hours, safety enhancements, greater combat capabilities and reliability.

Replacement

On 11 December 2013, Russian deputy prime minister Dmitry Rogozin revealed that Russia was planning to build a new fighter to replace the MiG-29. The Sukhoi Su-27 and its derivatives were to be replaced by the Sukhoi Su-57, but a different design was needed to replace the lighter MiGs. A previous attempt to develop a MiG-29 replacement, the MiG 1.44 demonstrator, failed in the 1990s. The concept came up again in 2001 with interest from India, but they later opted for a variant of the Su-57. Air Force commanders have hinted at the possibility of a single-engine airframe that uses the Su-57's engine, radar, and weapons primarily for Russian service.[15] This has since been revealed to be the Sukhoi Su-75 Checkmate.

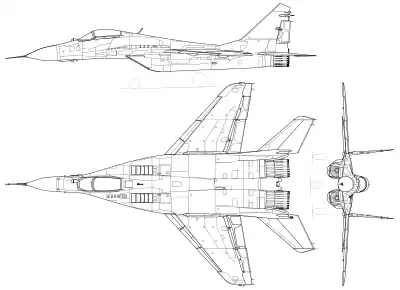

Design

Sharing its origins in the original PFI requirements issued by TsAGI, the MiG-29 has broad aerodynamic similarities to the Sukhoi Su-27, but with some notable differences. The MiG-29 has a mid-mounted swept wing with blended leading-edge root extensions (LERXs) swept at around 40°; there are swept tailplanes and two vertical fins, mounted on booms outboard of the engines. Automatic slats are mounted on the leading edges of the wings; they are four-segment on early models and five-segment on some later variants. On the trailing edge, there are maneuvering flaps and wingtip ailerons.[16]

The MiG-29 has hydraulic controls and a SAU-451 three-axis autopilot but, unlike the Su-27, no fly-by-wire control system. Nonetheless, it is very agile, with excellent instantaneous and sustained turn performance, high-alpha capability, and a general resistance to spins. The airframe consists primarily of aluminum with some composite materials, and is stressed for up to 9 g (88 m/s²) maneuvers. The controls have "soft" limiters to prevent the pilot from exceeding g and alpha limits, but the limiters can be disabled manually.[16]

Powerplant and range

_(cropped).png.webp)

The MiG-29 has two widely spaced Klimov RD-33 turbofan engines, each rated at 50 kilonewtons (11,200 lbf) dry and 81.3 kilonewtons (18,300 lbf) in afterburner. The space between the engines generates lift, thereby reducing effective wing loading, hence improving maneuverability. The engines are fed through intake ramps fitted under the leading-edge extensions (LERXs), which have variable ramps to allow high-Mach speeds. Due to their relatively short combustor, the engines produce noticeably heavier smoke than their contemporaries. As an adaptation to rough-field operations, the main air inlet can be closed completely and the auxiliary air inlet on the upper fuselage can be used for takeoff, landing and low-altitude flying, preventing ingestion of ground debris. Thereby the engines receive air through louvers on the LERXs which open automatically when intakes are closed. However the latest variant of the family, the MiG-35, eliminated these dorsal louvers, and adopted the mesh screens design in the main intakes, similar to those fitted to the Su-27.[17]

The MiG-29 has a ferry range of 1,500 km (930 mi) without external fuel tanks, and 2,100 km (1,300 mi) with external tanks.[18] The internal fuel capacity of the original MiG-29B is 4,365 L (960 imp gal; 1,153 US gal) distributed between six internal fuel tanks, four in the fuselage and one in each wing. For longer flights, this can be supplemented by a 1,500 L (330 imp gal; 400 US gal) centreline drop tank and, on later production batches, two 1,150 L (250 imp gal; 300 US gal) underwing drop tanks. In addition, newer models have been fitted with port-side inflight refueling probes, allowing much longer flight times by using a probe-and-drogue system.[19]

Cockpit

The cockpit features a conventional centre stick and left hand throttle controls. The pilot sits in a Zvezda K-36DM ejection seat.

The cockpit has conventional dials, with a head-up display (HUD) and a Shchel-3UM helmet mounted display, but no HOTAS ("hands-on-throttle-and-stick") capability. Emphasis seems to have been placed on making the cockpit similar to the earlier MiG-23 and other Soviet aircraft for ease of conversion, rather than on ergonomics. Nonetheless, the MiG-29 does have substantially better visibility than most previous Soviet jet fighters, thanks to a high-mounted bubble canopy. Upgraded models introduce "glass cockpits" with modern liquid-crystal (LCD) multi-function displays (MFDs) and true HOTAS.

Sensors

The baseline MiG-29B has a Phazotron RLPK-29 radar fire control system which includes the N019 Sapfir 29 look-down/shoot-down coherent pulse-Doppler radar and the Ts100.02-02 digital computer.

The N019 radar was not a new design, but rather a development of the Sapfir-23ML architecture used on the MiG-23ML. During the initial design specification period in the mid-1970s, Phazotron NIIR was tasked with producing a modern radar for the MiG-29. To speed development, Phazotron based its new design on work undertaken by NPO Istok on the experimental "Soyuz" radar program. Accordingly, the N019 was originally intended to have a flat planar array antenna and full digital signal processing, for a detection and tracking range of at least 100 km (62 mi) against a fighter-sized target. Prototype testing revealed this could not be attained in the required timeframe and still fit within the MiG-29's nose. Rather than design a new radar, Phazotron reverted to a version of the Sapfir-23ML's twisted-polarization cassegrain antenna and traditional analog signal processors, coupled with a new NII Argon-designed Ts100 digital computer to save time and cost. This produced a working radar system, but inherited the weak points of the earlier design, plaguing the MiG-29's ability to detect and track airborne targets at ranges available with the R-27 and R-77 missiles.

The N019 was further compromised by Phazotron designer Adolf Tolkachev’s betrayal of the radar to the CIA, for which he was executed in 1986. In response to all of these problems, the Soviets hastily developed a modified N019M Topaz radar for the upgraded MiG-29S aircraft. However, VVS was reportedly still not satisfied with the performance of the system and demanded another upgrade. The latest upgraded aircraft offered the N010 Zhuk-M, which has a planar array antenna rather than a dish, improving range, and a much superior processing ability, with multiple-target engagement capability and compatibility with the Vympel R-77 (or RVV-AE).

Armament

_(cropped).png.webp)

Armament for the MiG-29 includes a single GSh-30-1 30 mm (1.18 in) cannon in the port wing root. This originally had a 150-round magazine, which was reduced to 100 rounds in later variants, which only allows a few seconds of firing before running out of ammo. Original production MiG-29B aircraft cannot fire the cannon when carrying a centerline fuel tank as it blocks the shell ejection port. This was corrected in the MiG-29S and later versions.

Three pylons are provided under each wing (four in some variants), for a total of six (or eight). The inboard pylons can carry either a 1,150 L (250 imp gal; 300 US gal) fuel tank, one Vympel R-27 (AA-10 "Alamo") medium-range air-to-air missile, or unguided bombs or rockets. Some Soviet aircraft could carry a single nuclear bomb on the port inboard station. The outer pylons usually carry R-73 (AA-11 "Archer") dogfight air to air missiles, although some users still retain the older R-60 (AA-8 "Aphid"). A single 1,500 L (330 imp gal; 400 US gal) tank can be fitted to the centerline, between the engines.

The US has supplied AGM-88 HARM missiles to Ukraine. It appears that they are fired from MiG-29s. It was only disclosed after Russian forces showed footage of a tail fin from one of these missiles.[20] U.S. Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Colin Kahl has said this: "I would just point to two things. One, you know, a lot was made about the MiG-29 issue several months ago, not very much has been noticed about the sheer amount of spare parts and other things that we've done to help them actually put more of their own MiG-29s in the air and keep those that are in the air flying for a longer period of time. And then also, in recent PDA [Presidential Drawdown Authority] packages we've included a number of anti-radiation missiles that can be fired off of Ukrainian aircraft. They can have effects on Russian radars and other things."[21] Soviet era aircraft don't have the computer architecture to accept NATO standard weapons. The interface would be difficult; however with a "crude modification", such as an e-tablet, it would be possible.[22]

Operational history

While the MiG-29's true capabilities could only be estimated from the time it first appeared In 1977 until the mid-1980s, a combination of persistent intelligence and increasing access afforded by the Soviet foreign sales effort allowed a true appreciation of its capabilities. Early MiG-29s were very agile aircraft, capable of rivaling the performance of contemporary F-18 and F-16 aircraft. However, their relatively low fuel capacity relegated them to short-range air defense missions. Lacking HOTAS and an inter-aircraft data link, and requiring a very intensive "heads-down" approach to operating cockpit controls, the early MiG-29 denied pilots the kind of situational awareness routinely enjoyed by pilots operating comparable US aircraft. Analysts and Western pilots who flew examples of the MiG-29 thought this likely prevented even very good pilots from harnessing the plane's full combat capability. Later MiG-29s were upgraded to improve their capabilities.[23] The Soviet Union exported MiG-29s to several countries. Because 4th-generation fighter aircraft require the pilots to have extensive training, air-defense infrastructure, and constant maintenance and upgrades, MiG-29s have had mixed operational history with different air forces.[24]

Soviet Union and successor states

The MiG-29 was first publicly seen in the West when the Soviet Union displayed the aircraft in Finland on 2 July 1986. Two MiG-29s were also displayed at the Farnborough Airshow in Britain in September 1988. The following year, the aircraft conducted flying displays at the 1989 Paris Air Show where it was involved in a non-fatal crash during the first weekend of the show.[25] The Paris Air Show display was only the second display of Soviet fighters at an international air show since the 1930s. Western observers were impressed by its apparent capability and exceptional agility. Following the disintegration of the Soviet Union, most of the MiG-29s entered service with the newly formed Russian Air Force.

Russia

In July 1993, two MiG-29s of the Russian Air Force collided in mid-air and crashed away from the public at the Royal International Air Tattoo. No one on the ground sustained any serious injuries, and the two pilots ejected and landed safely.[26]

.jpg.webp)

The Russian Air Force grounded all its MiG-29s following a crash in Siberia on 17 October 2008. Following a second crash with a MiG-29 in east Siberia in December 2008,[27] Russian officials admitted that most MiG-29 fighters in the Russian Air Force were incapable of performing combat duties due to poor maintenance. The age of the aircraft was also an important factor as about 70% of the MiGs were considered to be too old to take to the skies. The Russian MiG-29s have not received updates since the collapse of the Soviet Union. On 4 February 2009, the Russian Air Force resumed flights with the MiG-29. However, in March 2009, 91 MiG-29s of the Russian Air Force required repair after inspections due to corrosion; approximately 100 MiGs were cleared to continue flying at the time.[28][29] The Russian Aerospace Forces started an update of its early MiG-29s to the more current MiG-29SMT standard,[18] but financial difficulties prevented delivery of more than three MiG-29 SMT upgrade to the Russian Aerospace Forces. Instead, the 35 MiG-29SMT/UBTs rejected by Algeria were bought by the Russian Aerospace Forces.[30] Russia placed an order for 16 new-build MiG-29SMTs on 15 April 2014, with delivery expected by 2017.[31]

On 4 June 2015, a MiG-29 crashed during training in Astrakhan.[32] A month later, another MiG-29 crashed near the village of Kushchevskaya in the Krasnodar region with the pilot safely ejecting.[33] A series of accidents in the Russian Aerospace Forces that happened in 2015 were caused mostly by overall increase of flights and training.[34]

On 20 April 2008, Georgian officials claimed a Russian MiG-29 shot down a Georgian Hermes 450 unmanned aerial vehicle and provided video footage from the ill-fated drone showing an apparent MiG-29 launching an air-to-air missile at it. Russia denies that the aircraft was theirs and says they did not have any pilots in the air that day. Abkhazia's administration claimed its own forces shot down the drone with an L-39 aircraft "because it was violating Abkhaz airspace and breaching ceasefire agreements."[35] UN investigation concluded that the video was authentic and that the drone was shot down by a Russian MiG-29 or Su-27 using an R-73 heat seeking missile.[36]

On 16 July 2014, a Ukrainian Su-25 was shot down, with Ukrainian officials stating that a Russian MiG-29 shot it down using a R-27T missile.[37][38] Russia denied these allegations.[39]

During the first half of September 2017, the Russian Aerospace Forces deployed some MiG-29SMT multirole combat aircraft to Khmeimim Airbase, near Latakia, in western Syria, becoming the first time the modernized version of the baseline Fulcrum jet was deployed to take part in the Syrian Air War.[40] The MiG-29SMT were involved in bombing missions and secondary strategic bombers escort duties.[41]

Two Russian MiG-29s operated by Wagner Group crashed near Sirte, Libya on 28 June 2020 and on 7 September 2020.[42]

Ukraine

In April 2014, during the Russian invasion of Crimea, 45 Ukrainian Air Force MiG-29s and 4 L-39 combat trainers were reportedly captured by Russian forces at Belbek air base. Most of the planes appeared to be in inoperable condition. In May, Russian troops dismantled them and shipped them back to Ukraine. On 4 August 2014, the Ukrainian government stated that a number of them had been put back into service to fight in the war in the east of the country.[43]

During the initial days of the war in Donbas in April 2014, the Ukrainian Air Force deployed some jet fighters over the Donetsk region to perform combat air patrols and show of force flights. Probably due to the limited number of jet fighters available, a MiG-29 belonging to the Ukrainian Falcons display team was spotted armed with a full air-to-air load and performing a low altitude fly by.[44]

In the evening of 7 August 2014, a Ukrainian Air Force MiG-29MU1, bort number 02 Blue, was shot down by an antiaircraft missile fired by pro-Russian rebels near the town of Yenakievo, and exploded in midair. The pilot ejected safely.[45][46][47]

On 17 August 2014, another Ukrainian Air Force MiG-29, bort number 53 White, tasked with air to ground duties against separatists' positions[48] was shot down by pro-Russian rebels in the Luhansk region. The Ukrainian government confirmed the downing. The pilot ejected safely and was recovered by friendly forces.[49][50]

As of 2018, the Lviv State Aircraft Repair Plant began domestically upgrading the MiG-29 to have multirole capability, known as the MiG-29MU2. Development was expected to be completed by 2019 and enter production in 2020.[51] The first upgraded MiG-29 was delivered to the Ukrainian Air Force in July 2020.[52] In August 2020, Ukraine began negotiations with Elbit Systems to help modernize the MiG-29 fleet.

On 29 May 2020, Ukrainian MiG-29s took part in the Bomber Task Force in Europe with American B-1B bombers for the first time in the Black Sea region.[53] In September 2020, B-52 bombers from the 5th Bomb Wing conducted vital integration training with Ukrainian MiG-29s and Su-27s inside Ukraine's airspace.[54][55]

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Su-27s and MiG-29s were used as air superiority fighters, with ten MiG-29s reported lost on the ground and in the air.[56][57][58][59][60][61][62]

In August 2022, a senior U.S. defense official disclosed that the Ukrainians have integrated the AGM-88 HARM missile onto their "MiG aircraft"[63] with video evidence of AGM-88 missiles fired by upgraded Ukrainian MiG-29s released by the Ukrainian Air Force few days later.[64] For a weapon that relies on digital display to fire, the question of how it has been integrated into the MiG-29’s analogue displays remains unanswered. The footage shows a commercial GPS having been installed along with a tablet of some kind.[65]

On 13 October 2022, a Ukrainian MiG-29 crashed during a combat mission. Its pilot is claimed to have destroyed a Shahed-136 drone with his cannon, and it is believed the debris from the drone collided with the aircraft and forced the pilot to eject. Ukrainian sources claim that the pilot shot down five drones and two cruise missiles shortly before the crash. The downed MiG-29 was wearing a livery similar to that of the Ukrainian Falcons display team. According to the Ukrainian State Bureau of Investigation: "the jet collided with debris from a destroyed drone, which caused massive damage to it to the point where it crashed near a village in northeast Vinnytsia. The pilot managed to eject and is currently receiving treatment in the hospital."[66][67]

On 20 September 2023, an Ukrainian Air Force MiG-29 was struck by a ZALA Lancet drone at the Dolgintsevo air base near Kryvyi Rih. A second drone was used as a spotter, recording the first Lancet's impact.[68]

India

India was the first international customer of the MiG-29, outside of the Warsaw Pact. The Indian Air Force (IAF) placed an order for 44 aircraft (40 single-seat MiG-29 9.12Bs and four twin-seat MiG-29UBs) in 1984, and the MiG-29 was officially inducted into the IAF in 1987. In 1989, an additional 26 aircraft were ordered, and 10 more advanced MiG-29 9.13s were bought in 1994. Since then, the aircraft has undergone a series of modifications with the addition of new avionics, subsystems, turbofan engines and radars.[69]

Indian MiG-29s were used extensively during the 1999 Kargil War in Kashmir by the Indian Air Force to provide fighter escort for Mirage 2000s attacking targets with laser-guided bombs.[70]

The MiG-29's good operational record prompted India to sign a deal with Russia in 2005 and 2006 to upgrade all of its MiG-29s for US$888 million. Under the deal, the Indian MiGs were modified to be capable of deploying the R-77/RVV-AE (AA-12 'Adder') air-to-air missile. The missiles had been tested in October 1998 and were integrated into the IAF's MiG-29s. The IAF has also awarded the MiG Corporation another US$900 million contract to upgrade all of its 69 operational MiG-29s. These upgrades will include a new avionics kit, with the N019 radar being replaced by a Phazotron Zhuk-M radar. The aircraft is also being equipped to enhance beyond-visual-range combat ability and for air-to-air refuelling to increase endurance.[71] In 2007, Russia also gave India's Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) a licence to manufacture 120 RD-33 series 3 turbofan engines for the upgrade.[72] The upgrade will also include a new weapon control system, improved cockpit ergonomics, air-to-air missiles, high-accuracy air-to-ground missiles and guided bombs. The first six MiG-29s will be upgraded in Russia while the remaining 63 MiGs will be upgraded at the HAL facility in India. India also awarded a multi-million-dollar contract to Israel Aircraft Industries to provide avionics and subsystems for the upgrade.[73]

In March 2009, the Indian Air Force expressed concern after 90 MiG-29s were grounded in Russia.[74] After carrying out an extensive inspection, the IAF cleared all MiG-29s in its fleet as safe in March 2009.[75] In a disclosure in Parliament, Defence Minister A. K. Antony said the MiG-29 is structurally flawed in that it has a tendency to develop cracks due to corrosion in the tail fin. Russia has shared this finding with India, which emerged after the crash of a Russian Air Force MiG-29 in December 2008. "A repair scheme and preventive measures are in place and IAF has not encountered major problems concerning the issue", Antony said.[76] Despite concerns of Russia's grounding, India sent the first six of its 78 MiG-29s to Russia for upgrades in 2008. The upgrade program will fit the MiGs with a phased array radar (PESA) and in-flight re-fuelling capability.[24]

In January 2010, India and Russia signed a US$1.2 billion deal under which the Indian Navy would acquire 29 additional MiG-29Ks, bringing the total number of MiG-29Ks on order to 45.[77] The MiG-29K entered service with the Indian Navy on 19 February 2010.[78]

The upgrades to Indian MiG-29s will be to the MiG-29UPG standard. This version is similar to the SMT variant but differs by having a foreign-made avionics suite.[79] The upgrade to latest MiG-29UPG standard is in process, which will include latest avionics, Zhuk-ME Radar, engine, weapon control systems, DRDO/DARE developed D-29 electronic warfare system greatly enhancing multi-role capabilities and survivability.[80][81] The first three aircraft were delivered in December 2012, over two years behind schedule.[82]

An IAF MiG-29 crashed near Jalandhar in Punjab on 8 May 2020 with its pilot ejected safely after the aircraft failed to respond. A court of inquiry has been ordered in the incident.[83]

In 2020, India ordered 21 MiG-29s at an affordable price. These aircraft will be manufactured from airframes built in late 1980s but never assembled. Mikoyan will upgrade these aircraft before delivery to the Indian Air Force. In the process, India becomes the last export customer of the original airframe of MiG-29.[84][85][86] Russia has sent a commercial proposal for 21 MiG-29 aircraft to be refurbished for the Indian Air Force.[87]

Yugoslavia and Serbia

Yugoslavia was the first European country outside the Soviet Union to operate the MiG-29. The country received 14 MiG-29Bs and two MiG-29UBs from the USSR in 1987 and 1988. The MiG-29s were put into service with the 127th Fighter Aviation Squadron, based at Batajnica Air Base, north of Belgrade, Serbia.[88]

Yugoslav MiG-29s saw little combat during the breakup of Yugoslavia, and were used primarily for ground attacks. Several Antonov An-2 aircraft used by Croatia were destroyed on the ground at Čepin airfield near Osijek, Croatia in 1991 by a Yugoslav MiG-29, with no MiG-29 losses.[89] At least two MiG-29s carried out an air strike on Banski Dvori, the official residence of the Croatian Government, on 7 October 1991.[90]

The MiG-29s continued their service in the subsequent Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Because of the United Nations arms embargo against the country, the condition of the MiG-29s worsened as aircraft were not maintained according to rules and general overhaul scheduled for 1996 and 1997 was not conducted.[91]

Six MiG-29s were shot down during the NATO intervention in the Kosovo War, three by USAF F-15s, one by a USAF F-16, and one by a Royal Netherlands Air Force F-16.[92][93] However, one aircraft, according to its pilot, was hit by friendly fire from the ground.[94] Another four were destroyed on the ground.[95] One Argentine source claims that a MiG-29 shot down an F-16 on 26 March 1999,[96] but this kill is disputed, as the F-16C in question was said to have crashed in the US that same day.[97]

The Air Force of Serbia and Montenegro continued flying its remaining five MiG-29s at a very low rate after the war with one of them crashing on 7 July 2009. In spring 2004, news appeared that MiG-29 operations had ceased, because the aircraft could not be maintained,[89] but later the five remaining airframes were sent to Russia for overhaul. The small Serbian MiG-29 fleet along with other jets were grounded for four months during summer 2014 due to a battery procurement issue. The Serbian Air Force operates 14 MiG-29s as of 2020 with two more to be added in 2021.[98]

In November 2016, Russia had agreed to donate six of its MiG-29s free of charge, if Serbia would pay the repair costs of $50 million for them.[99] At the end of January 2017, Serbian defense minister Zoran Đorđević said that Belarus also agreed to donate eight of its MiG-29s to Serbia on a no-pay basis.[100] In early October 2017, Russia completed the delivery of all the six MiG-29s. The aircraft were transferred to Serbia on board an Antonov An-124 transport aircraft.[101] On 25 February 2019, Belarus formally handed four MiG-29s to the Serbian military during a ceremony held at the 558th Aircraft Repair Plant in Baranavichy. This increased the Serbian Air Force's fleet to 14 MiG-29s.[102] Serbia plans to spend about €180–230 million on modernization of its entire MiG-29 fleet.[103][104]

Germany

East Germany bought 24 MiG-29s (20 MiG-29As, four MiG-29UBs), which entered service in 1988–1989 in 1./JG3 "Wladimir Komarow" in Preschen in Brandenburg.[105] After the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and reunification of Germany in October 1990, the MiG-29s and other aircraft of the East German Air Forces of the National People's Army were integrated into the West German Luftwaffe.[106] Initially the 1./JG3 kept its designation. In April 1991 both 1./JG3's MiG-29 squadrons were reorganised into the MiG-29 test wing ("Erprobungsgeschwader MiG-29"), which became JG73 "Steinhoff" and was transferred to Laage near Rostock in June 1993.

The Federation of American Scientists claims the MiG-29 is equal to, or better than the F-15C in short aerial engagements because of the Helmet Mounted Weapons Sight (HMS) and better maneuverability at slow speeds.[107] This was demonstrated when MiG-29s of the German Air Force participated in joint DACT exercises with US fighters.[108][109] The HMS was a great help, allowing the Germans to achieve a lock on any target the pilot could see within the missile field of view, including those almost 45 degrees off boresight.[110] However, the German pilots who flew the MiG-29 admitted that while the Fulcrum was more maneuverable at slow speeds than the F-15 Eagle, F-16 Fighting Falcon, F-14 Tomcat, and F/A-18 Hornet and its Vympel R-73 dogfight missile system was superior to the AIM-9 Sidewinder of the time, in engagements that went into the beyond visual range arena, the German pilots found it difficult to multi-task locking and firing the MiG-29's Vympel R-27 missile (German MiG-29s did not have access to the more advanced Vympel R-77 that equips more advanced MiG-29 versions) while trying to avoid the longer range and advanced search and track capabilities of the American fighters' radars and AIM-120 AMRAAM. The Germans also stated that the American fighters had the advantage in both night and bad weather combat conditions. The Luftwaffe's assessment of the MiG-29 was that the Fulcrum was best used as a point defense interceptor over cities and military installations, not for fighter sweeps over hostile airspace. This assessment ultimately led Germany to not deploy its MiG-29s in the Kosovo War during Operation Allied Force, though Luftwaffe pilots who flew the MiG-29 admitted that even if they were permitted to fly combat missions over the former Yugoslavia they would have been hampered by the lack of NATO-specific communication tools and identification friend or foe systems.[111][112]

Beginning in 1993, the German MiGs were stationed with JG73 "Steinhoff" in Laage near Rostock. During the service in the German Air Force, one MiG-29 ("29+09") was destroyed in an accident on 25 June 1996 due to pilot error. By 2003, German Air Force pilots had flown over 30,000 hours in the MiG-29. In September 2003, 22 of the 23 remaining machines were sold to the Polish Air Force for the symbolic price of €1 per item.[113] The last aircraft were transferred in August 2004.[114] The 23rd MiG-29 ("29+03") was put on display at Laage.[115]

Libya

In 2020 it was reported that MiG-29 aircraft was flown by forces aligned with Khalifa Haftar in Libya.[116] On 11 September 2020, United States Africa Command stated that two MiG-29s, operated by Russian speaking personnel, crashed in Libya due to unknown reasons, the first on 28 June 2020, the second on 7 September 2020.[117] It was announced that MiG-29s and Su-24s are to be delivered to the Libyan Air Force from Russia.[118]

Peru

The Peruvian Air Force acquired 21 MiG-29S fighters from Belarus in 1997, as part of a package that also included 18 Su-25 attack aircraft. The following year an additional 3 MiG-29 aircraft were acquired from Russia. At the same time, Peru contracted with Mikoyan to upgrade 8 aircraft to the MiG-29SMP standard, with an option to upgrade the remainder of the Peruvian inventory. The Peruvian MiG-29s are based at FAP Captain José Abelardo Quiñones González International Airport in northern Peru, equipping Escuadrón Aéreo 612 (Fighter Squadron 612 "Fighting Roosters").[119]

Poland

The first 12 MiG-29s delivered to Poland were nine MiG-29As and three MiG-29UBs in 1989–1990. The aircraft were based at Mińsk Mazowiecki and used by the 1st Fighter Aviation Regiment, which was reorganized in 2001 as 1 Eskadra Lotnictwa Taktycznego (1. elt), or 1st Tactical Squadron (TS). In 1995–1996, 10 used examples were acquired from the Czech Republic (nine MiG-29As, one MiG-29UB). After the retirement of its MiG-23s in 1999, and MiG-21s in 2004, Poland was left for a time with only these 22 MiG-29s in the interceptor role.

Of the 22 MiG-29s Poland received from the German Air Force in 2004, a total of 14 were overhauled and taken into service. They were used to equip the 41st Tactical Squadron (41. elt), replacing its MiG-21s. As of 2008, Poland was the biggest NATO MiG-29 user. Poland had 31 active MiG-29s (25 MiG-29As, six MiG-29UBs) as of 2017.[120] They are stationed with the 1st Tactical Squadron at the 23rd Air Base near Mińsk Mazowiecki and the 41st TS at the 22nd Air Base near Malbork.

There have been unconfirmed reports that Poland has at one point leased a MiG-29 from its own inventory to Israel for evaluation and the aircraft has since been returned to Poland, as suggested by photographs of a MiG-29 in Israeli use. Three Polish MiG-29As were reported in Israel for evaluation between April and May 1997 in the Negev Desert. On 7 September 2011, the Polish Air Force awarded a contract to the WZL 2 company to modernise its MiG-29 fleet to be compatible with Polish F-16s.[121]

Four MiG-29s from 1. elt participated in the Baltic Air Policing mission in 2006, while 41. elt aircraft did so in 2008, 2010 and 2012. Polish MiG-29s played the aggressor role in the NATO Tactical Leadership Programme (TLP) joint training program in Albacete in 2011, 2012 and 2013.[122]

On 18 December 2017, a MiG-29 crash-landed in a forest near the 23rd Air Base while performing a landing approach.[123] The pilot did not eject, but survived the crash with minor injuries. This was the first crash of a MiG-29 during its nearly three decades long operational history in the Polish Air Force.[124] On 6 July 2018, another MiG-29 crashed near Pasłęk, with its pilot dying in an ejection attempt. Technical issues are suspected to have played a role in the crash.[125] Another crash followed on 4 March 2019. This time the pilot ejected and survived.[126]

On 8 March 2022, Poland announced a willingness to transfer their operational fleet of MiG-29 aircraft to the US via the Ramstein Air Base, in exchange for aircraft of a similar role and operational capability, with the intent of transferring the MiG-29s to Ukraine to use in the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[127]

On 16 March 2023, Polish President Andrzej Duda announced that Poland would transfer four operational MIG-29s to Ukraine, with the understanding that additional aircraft would be delivered after servicing and preparation. Poland is the first NATO country to provide Ukraine with fighter aircraft.[128]

On 13 April, Boris Pistorius German Defence Minister, has announced that Germany approved the transfer of five MiG-29s to Ukraine. German approval was necessary because these aircraft belonged to the German Democratic Republic, which were then transferred to Poland in 2004.[129]

Iraq

Iraq received a number of MiG-29 fighters and used them to engage Iranian equivalent opponents during the later stages of the Iran–Iraq War.

By August 1990, at the time of the Invasion of Kuwait, the Iraqi Air Force had received 39 MiG-29 (9.12B) Fulcrum-As. Iraq was reportedly unsatisfied that they did not receive the R-73 and R-27T missiles that Coalition intelligence had assessed as a great threat, instead receiving R-60MK missiles. As a result they did not order anymore aircraft. Iraq was reportedly able to modify their MiG-29s to carry both drop tanks and the TMV-002 Remora ECM pod.[130]

MiG-29s saw combat in the 1991 Persian Gulf War with the Iraqi Air Force. Five MiG-29s were shot down by USAF F-15s.[131] Some Russian sources reported that one British Panavia Tornado, ZA467, was shot down in northwestern Iraq by a MiG-29 piloted by Jameel Sayhood.[132][133] UK sources claim this Tornado to have crashed on 22 January on a mission to Ar Rutbah.[134] Other Iraqi air-to-air kills are reported in Russian sources, where the US claims other cases of combat damage, such as a B-52 which the US claims was hit by friendly fire, when an AGM-88 high-speed, anti-radiation missile (HARM) homed on the fire-control radar of the B-52's tail gun; the bomber returned to base and was subsequently renamed "In HARM's Way".[135] It is believed that an F-111 was hit by a missile fired by a MiG-29 but it was able to return to base.[136]

Iraq's original fleet of 37 MiG-29s was reduced to 12 after the Gulf War. One MiG-29 was damaged, and four were evacuated to Iran. The remaining 12 aircraft were withdrawn from use in 1995 because the engines needed to be overhauled but Iraq could not send them off for that work.[137]

After the American-led 2003 invasion of Iraq and disbandment of the Ba'athist Iraqi Army in May of the same year,[138] the remaining Soviet-made and Chinese-made fighters of the Iraqi Air Force had been decommissioned.

Syria

Syrian Arab Air Force MiG-29s have sometimes encountered Israeli fighter and reconnaissance aircraft. Two Israeli F-15Cs reportedly shot down two MiG-29As on 2 June 1989 under unclear circumstances.[139][140]

Further reports claim that on 14 September 2001 two Syrian Air Force MiG-29s were shot down by two Israeli F-15Cs while the MiGs were intercepting an Israeli reconnaissance aircraft off the coast of Lebanon. However, both Syria and Israel deny that this occurred.[140][141][142]

Syrian MiG-29s entered the Syrian Civil War in late October 2013, attacking Free Syrian Army insurgents with unguided rockets and bombs in Damascus.[143]

A Syrian MiG-29SM crashed on 7 March 2020 near Shayrat Airbase. Marking the first crash of the plane in the Syrian Air Force since 2001. According to avia.pro the aircraft may have been shot down by MANPADS operated by the Syrian Opposition.[144][145]

North Korea

The Korean People's Air Force is believed to operate about 18 MiG-29 which are assigned to the 55th Air Regiment based at Sunchon Air Base. In addition to 13 MiG-29 (9.12B) Fulcrum-As and 2 Fulcrum-B trainers that were delivered in 1987, North Korea also became the only Cold War export customer and licensed manufacturer of the Fulcrum-C.[146] Called the MiG-29S-13 (9.13B) Fulcrum-C, they were delivered to North Korea from the USSR/Russia between 1991-1992 in knock down parts. Only three S-13s were completed due to Russia refusing to supply more parts to North Korea. The first locally built Fulcrum-C flew on 15 April 1993.[146] These were first encountered and photographed by the USAF in March 2003 when a pair of KPAF MiG-29s intercepted an USAF RC-135S Cobra Ball reconnaissance aircraft.[147][148]

Sudan

_MTI-2.jpg.webp)

There have been occasional claims regarding the use of Sudanese Air Force MiG-29s against insurgent forces in Darfur. However, whereas Mi-24 combat helicopters as well as Nanchang A-5 or, more recently, Su-25 ground-attack aircraft have been spotted and photographed on Darfurian air fields, no MiG-29s have been observed. On 10 May 2008, a Darfur rebel group, the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) mounted an assault on the Sudanese capital. During this action, the JEM shot down a Sudanese Air Force MiG-29 with 12.7 and 14.5 mm (0.500 and 0.571 in) heavy machine gun fire while it was attacking a convoy of vehicles in the Khartoum suburb of Omdurman. The aircraft was piloted by a Russian mercenary. He was killed in action as his parachute did not open after ejecting.[149][150][151] On 14 November 2008 Sudanese Ministry of Defence admitted that Sudan had received 12 MiG-29 from Russia.[152] An anonymous Russian source claimed that the aircraft had been delivered before 2004.[152]

During the brief 2012 South Sudan–Sudan border conflict, on 4 April 2012, Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) claimed the downing of a Sudanese MiG-29 using antiaircraft guns. The Sudan government denied the claim.[153] On 16 April 2012, the SPLA issued a second claim about the downing of a Sudanese MiG-29.[154] It was not clear if this second claim referred to the previous one.

On 15 April 2023, a Sudanese MiG-29 was captured on film firing missiles over Khartoum during a skirmish with paramilitary forces.[155]

On 25 May 2023, a Sudanese MiG-29 was filmed being shot down by the RSF over Omdurman.[156] The pilot ejected and survived, although he was wounded and captured.[157]

United States

In 1997, the United States purchased 21 Moldovan MiG-29 aircraft under the Nunn–Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction program. Fourteen were MiG-29S models, which are equipped with an active radar jammer in its spine and are capable of being armed with nuclear weapons. Part of the United States’ motive to purchase these aircraft was to prevent them from being sold to Iran.[158] This purchase could also provide the tactical jet fighter communities of the USAF, the USN and the USMC with a working evaluation and data for the MiG-29, and possibly for use in dissimilar air combat training. Such information may prove valuable in any future conflicts and can aid in the design and testing of current and future weapons platforms. In late 1997, the MiGs were delivered to the National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, though many of the former Moldovan MiG-29s are believed to have been scrapped. Some of these MiG-29s are currently on open display at Nellis AFB, Nevada; NAS Fallon, Nevada; Goodfellow AFB, Texas; and Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio.

Others

A Cuban MiG-29UB shot down two Cessna 337s belonging to the organisation Brothers to the Rescue in 1996, after the aircraft approached Cuban airspace.[159]

According to some reports, in the 1999 Eritrean-Ethiopian War, a number of Eritrean MiG-29s were shot down by Ethiopian Su-27s piloted by Russian mercenaries.[160] It was reported that local pilots were trained by instructors from those nations.[161] There are also some other reports of Eritrean MiG-29s shooting down two Ethiopian MiG-21s, three MiG-23s.[162] The claim that an Eritrean MiG-29 shot down an Ethiopian Su-25 was later debunked, since the missing Ethiopian Su-25TK was damaged in an accident in May 2000, is actually stored and used for spares at Bishoftu Air Base.

As of 2022, Jane's Information Group reported the Bangladesh Air Force (BAF) operated 8 MiG-29s (6B & 2UB).[163]

After the end of the 1994 civil war, newly reunified Yemen inherited several intact MiG-29s, bought by South Yemen a few months earlier.[164] In 1995-1996, Yemen also received two additional jets from Kazakhstan.[165] In 2001, a major arms deal including the purchase of up to 36 upgraded MiG-29s was signed, with deliveries starting in June 2002.[165] Equipped with N019MP radar and an advanced fire control system, they became the most advanced combat aircraft in the Yemeni Air force arsenal. They are compatible with Kh-31P and Kh-29T guided air-to-ground missiles, as well as R-77 air-to-air missiles.[165]

Potential operators and failed bids

Before the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Finland had a policy of splitting procurement of armaments between western, eastern and domestic suppliers. The MiG-29 was planned to replace the Finnish Air Force's MiG-21 fighters up to 1988, with test flights having been done.[166]

In the second half of the 1980s, the Soviet Union offered the MiG-29 to Libya. The offer was turned down, as the weapons system and radar of the MiG-29 were assessed as similar to those of the MiG-23MLD already in service with the Libyan Arab Air Force. The MiG-29's price was also deemed much too high.[167]

In 1989, Zimbabwe ordered a squadron's worth of MiG-29s to the USSR. Some Air Force of Zimbabwe personnel travelled to Russia for conversion courses, but in 1992 the deal was cancelled, as the geopolitical situation of the region was stabilising.[168]

In December 2008, Russia moved to expand its military influence in the Middle East when it announced it was giving Lebanon 10 fighter jets, that would have been the most significant upgrade of Lebanon's military since the civil war ended almost two decades before. A Russian defence ministry representative said it was giving secondhand MiG-29s to Lebanon for free. This was to be part of a defence cooperation deal that would have included Lebanese military personnel training in Russia.[169] On 29 February 2010, Russia agreed to change the offer to 10 Mi-24 attack helicopters based on a Lebanese request.[170]

In 2021 Russia offered the Argentine Air Force a batch of 15 MiG-29 fighters and another of Su-30 fighters with 12 units and seek also the sale of Yak-130 training jet and Mil Mi-17 helicopters.[171]

Variants

Original Soviet variants

- MiG-29A (Product 9.12)[172]

- Initial production version for Soviet Air Force; entered service in 1983. NATO reporting name is "Fulcrum-A". Variant possessed the Phazotron N019 Rubin radar, OEPS-29 optical-electronic sighting system and helmet mounted sight.

- MiG-29A (Product 9.12A)

- Export variant of the 9.12 for Warsaw Pact pact countries which included a downgraded RPLK-29E radar, downgraded OEPrNK-29E optoelectronic and navigation systems and older IFF transponders. This variant also lacked the capability to deliver nuclear weapons. Delivered to East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Romania.

- MiG-29A (Product 9.12B)

- Export variant of the 9.12 for non-Warsaw Pact pact countries which included a further downgraded radar and avionics. Delivered to India, Iraq, Syria, North Korea, Cuba, Malaysia, Myanmar and Eritrea.

- MiG-29UB (Product 9.51)

- Twin seat training model. Infrared sensor mounted only, no radar. NATO reporting name is "Fulcrum-B".

- MiG-29A (Product 9.13)

- Update of the initial production version; entered service in 1986. NATO reporting name is "Fulcrum-C". Variant possessed an enlarged dorsal spine to accommodate a larger No.1 fuel tank and the installation of the L-203BE Gardenyia-1 jammer that was lacking on the initial 9.12 version. This enlarged spine earned the 9.13 version and its successors the nickname of "Fatback".

- MiG-29S-13 (Product 9.13B)

- Export variant of the 9.13 provided to North Korea in knock parts and built in Panghyon between 1991-1992. Like the 9.13, it has the Gardenyia-1 jammer but has downgraded avionics and no IFF.[173]

- MiG-29S (Product 9.13S)

- The MiG-29S was an update of the original 9.13 model retaining the NATO reporting code "Fulcrum-C" and featured flight control system improvements; a total of four new computers provided better stability augmentation and controllability with an increase of 2° in angle of attack (AoA). An improved mechanical-hydraulic flight control system allowed for greater control surface deflections. The MiG-29S can carry 1,150 L (250 imp gal; 300 U.S. gal) under wing drop tanks and a centerline tank. The inboard underwing hardpoints allow a tandem pylon arrangement for carrying a larger payload of 4,000 kg (8,800 lb). Overall maximum gross weight was raised to 20,000 kg (44,000 lb). This version also included new avionics and the new Phazotron N019M radar and Built-In Test Equipment (BITE) to reduce dependence on ground support equipment. Development of this version was initiated due to multiple systems being compromised to the West by Phazotron engineer Adolf Tolkachev. This was the final version of the MiG-29 produced before the collapse of the Soviet Union and only limited numbers were produced.

Upgraded variants based on original airframe

- MiG-29S (Product 9.12S)

- Post Soviet upgrade for older 9.12 variants incorporating the changes developed for version 9.13S.

- Mig-29SD (Product 9.12SD)

- Export variant of upgraded 9.12S with downgraded versions of radar and avionics.

- MiG-29SE (Product 9.13SE)

- Export variant of the 9.13S with slightly downgraded N-019ME radar with multiple target tracking ability and RVV-AE (R-77 missile) compatibility. The first export model MiG-29 with underwing drop tanks; the inner underwing pylons can carry over 500 kg (1,100 lb) bombs in side by side tandem pairs. Its weapons mix includes R-27T1, R-27ER1 and R-27ET1 medium-range missiles. The aircraft can be fitted with active ECM systems, weapons guidance aids, improved built-in check and training systems. The MiG-29SE can simultaneously engage two air targets.

- MiG-29SM (Product 9.13M)

- Similar to the 9.13, but with the ability to carry guided air-to-surface missiles and TV- and laser-guided bombs. NATO reporting code is "Fulcrum-C".

- MiG-29SM (SyAF)

- For the Syrian Air Force, and based on the MiG-29SM, except the Syrian MiG-29SM uses the 9.12 airframe. RAC MiG developed a special variant for Syria.[174]

- MiG-29G/MiG-29GT

- East German MiG-29 / 29UB upgraded to NATO standards, with work done by MiG Aircraft Product Support GmbH (MAPS), a joint venture company form between MiG Moscow Aviation Production Association and DaimlerChrysler Aerospace in 1993.[175]

- MiG-29AS/MiG-29UBS

- Slovak Air Force performed an upgrade on their MiG-29/-29UB for NATO compatibility. Work is done by RAC MiG and Western firms, starting from 2005. The aircraft now has navigation and communications systems from Rockwell Collins, an IFF system from BAE Systems, new glass cockpit features multi-function LC displays and digital processors and also fitted to be integrate with Western equipment in the future. However, the armaments of the aircraft remain unchanged. 12 out of 21 of the entire MiG-29 fleet were upgraded and had been delivered as of late February 2008.

- MiG-29 Sniper

- Upgrade planned for the Romanian Air Force by DASA, Aerostar and Elbit. DASA was responsible for program management, technical support and the test flight program (together with Elbit), Elbit was responsible for developing the avionics package, while Aerostar implemented the upgrades on the aircraft. The first flight occurred on 5 May 2000.[176][177] The upgrades included the installation of a new modular multirole computer based on the MIL-STD-1553B data bus, upgraded Western avionics, new radio stations, hybrid navigation system composed of an inertial navigation system and coupled with GPS receiver, identification system, two 152 mm × 203 mm (6.0 in × 8.0 in) MFCDs, a Head-Up Display equipped with UFCP front control panel, new RWR, new HOTAS and new ADC. The addition of a new radar and the integration of Western weapons while maintaining Russian ones were also expected.[178] The program halted due to various reasons, along with the retiring of Romanian MiG-29s in 2003, the Romanian Government deciding to further invest in the MiG-21 LanceR program.[179]

%252C_Russia_-_Air_Force_AN2269907.jpg.webp)

- MiG-29SMT (Product 9.17)

- The MiG-29SMT is an upgrade of first-generation MiG-29s (9.12 to 9.13) using enhancements on the MiG-29M. Additional fuel tanks in a further enlarged spine provide a maximum internal flight range of 2,100 km (1,300 mi). The cockpit has an enhanced HOTAS design, two 152 mm × 203 mm (6.0 in × 8.0 in) colour liquid crystal MFDs and two smaller monochrome LCDs. The MiG-29A lacked an advanced air-to-ground capability, thus the SMT upgrade adds the upgraded Zhuk-ME radar with air-to-ground radar detection and integrates air-to-ground guided weapons.[180] It also has upgraded RD-33 ser.3 engines with afterburning thrust rated at 81 kN (18,000 lbf) each. The weapons load was increased to 4,500 kg (9,900 lb) on six underwing and one ventral hardpoints, with similar weapon choices to the MiG-29M. It can also accommodate non-Russian origin avionics and weapons.[181][182]

- MiG-29BM

- The MiG-29BM (probably Belarusian Modernised, possibly Bolyshaya Modernizaciya – large modernization) is an upgrade conducted by the ARZ-558 aircraft repair plant in Baranovichi, Belarus. It is a strike variant of the MiG-29 and the Belarusian counterpart to the Russian MiG-29SMT. It includes improvements to weapons, radar, as well as adding non-retractable air-air refueling ability. They entered service in 2003 and it is estimated, that ten or so were modernized to BM standard.[183] The Bangladesh Air Force upgraded its MiG-29Bs similar to BM standard.[184]

- MiG-29UBT (Product 9.51T)

- SMT standard upgrade for the MiG-29UB. Namely users, Algeria and Yemen.[185][186]

- MiG-29UPG

- The UPG was a new modification intended for the MiG-29s used by the Indian Air Force. The Indian UPG version is similar to the SMT variant but differs by having a foreign-made avionics suite integrated within it.[79] The weapons suite is the same as the SMT and K/KUB versions.[79] It made its maiden flight on 4 February 2011. The version includes the new Zhuk-M radar, new avionics, an IFR probe, as well as new enhanced RD-33 Series 3 turbofan engines, and the DRDO/DARE D-29 Electronic Warfare System.[80] The modernization is part of a $900 million contract to upgrade the 69 fighter fleet.

- MiG-29SMP / MiG-29UBP

- The SMP/UBP are upgrades for the Peruvian Air Force MiG-29 fleet. In August 2008 a contract of US$106 million was signed with RAC MiG for this custom SM upgrade of an initial batch of eight MiG-29, with a provision for upgrading all of Peru's MiG-29s.[187] The single-seat version is designated SMP, whereas the twin-seat version is designated UBP. It features an improved ECM suite, avionics, sensors, pilot interface, and a MIL-STD-1553 databus. The interfaces include improved IRST capabilities for enhanced passive detection and tracking as well as better off-boresight launch capabilities, one MFCD and HOTAS.[188] The N019M1 radar, a heavily modified and upgraded digital version of the N019 radar, replaces the standard N010 Zhuk-M of the MiG-29SMT. The upgrade also includes a structural life-extension program (SLEP), overhauled and upgraded engines, and the addition of an in-flight refuelling probe.[189]

- MiG-29MU1

- A Ukrainian modernization of the MiG-29.[190]

- MiG-29MU2

- A further Ukrainian modernization of the MiG-29, focused on air to ground munitions.[191]

Second-generation variants with modified airframe

- MiG-29M / MiG-33 (Product 9.15)

- Advanced multirole variant, with a redesigned airframe, mechanical flight controls replaced by a fly-by-wire system and powered by enhanced RD-33 ser.3M engines. NATO reporting code is "Fulcrum-E".

- MiG-29UBM (Product 9.61)

- Two-seat training variant of the MiG-29M. Never built. Effectively continued under the designation 'MiG-29M2'.

- MiG-29M2 / MiG-29MRCA

- Two-seat version of MiG-29M. Identical characteristics to MiG-29M, with a slightly reduced ferry range of 1,800 km (1,100 mi).[192] RAC MiG presented in various air shows, including Fifth China International Aviation and Aerospace Exhibition (CIAAE 2004),[193] Aero India 2005,[194][195] MAKS 2005.[196] It was once given designation MiG-29MRCA for marketing purpose and now evolved into the current MiG-35.

- MiG-29OVT

- The aircraft is one of the six pre-built MiG-29Ms before 1991, later received thrust vectoring engine and fly-by-wire technology. It served as a thrust-vectoring engine testbed and technology demonstrator in various air shows to show future improvement in the MiG-29M. It has identical avionics to the MiG-29M. The only difference in the cockpit layout is an additional switch to turn on vector thrust function. The two RD-133 thrust-vectoring engines, each features unique 3D rotating nozzles which can provide thrust vector deflection in all directions. However, despite its thrust-vectoring, other specifications were not officially emphasized. It is usually used as an aerobatic demonstrator and has been demonstrated along with the MiG-29M2 in various air shows around the world for potential export.[197]

- MiG-29K (Product 9.31)

- Naval variant based on MiG-29M, the letter "K" stands for "Korabelnogo bazirovaniya" (deck-based). It features folding wings, arrestor gear, and reinforced landing gear. Originally intended for the Admiral Kuznetsov class aircraft carriers, it had received series production approval from the Russian Ministry of Defence but was grounded in 1992 due to shift in military doctrine and financial difficulties.[198] The MiG Corporation restarted the program in 1999. On 20 January 2004, the Indian Navy signed a contract of 12 single-seat MiG-29K and four two-seat MiG-29KUB.[198] Modifications were made for the Indian Navy requirement. Production MiG-29K and MiG-29KUB share a two-seater size canopy. The MiG-29K has radar absorbing coatings to reduce radar signature. Cockpit displays consist of wide HUD and three (seven on MiG-29KUB) colour LCD MFDs with a Topsight E helmet-mounted targeting system. It has a full range of weapons compatible with the MiG-29M and MiG-29SMT.[199] NATO reporting code is "Fulcrum-D".

- MiG-29KUB (Product 9.47)

- Identical characteristic to the MiG-29K but with tandem twin seat configuration. The design is to serve as trainer for MiG-29K pilot and is full combat capable. The first MiG-29KUB developed for the Indian Navy made its maiden flight at the Russian Zhukovsky aircraft test centre on 22 January 2007. NATO reporting code is "Fulcrum-D".

- MiG-35

.jpg.webp)

- A development of the MiG-29M/M2 and MiG-29K/KUB. NATO reporting code is "Fulcrum-F".

Operators

.jpg.webp)

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

_Pichugin-1.jpg.webp)

_at_Lviv_International_Airport.jpeg.webp)

_MRD-2.jpg.webp)

- Algerian Air Force – 26 MiG-29s in service in January 2014.[200][201] 14 MiG-29M/M2s on order.[202][203]

- Azerbaijani Air Forces – 13 MiG-29s in operational use in January 2014[200][201]

- Bangladesh Air Force – 6 MiG-29Bs and 2 MiG-29UBs in service as of 2021. Four MiG-29Bs were upgraded for life extension in Belarus.Rest were upgraded in 2021-2022.[204][205]

- Belarusian Air Force – 41 MiG-29s in inventory as of January 2014[200]

- Bulgarian Air Force – 11 MiG-29s and 3 MiG-29UB used for conversion training in inventory as of 2022.[206]

- Chadian Air Force – 3 MiG-29s[207] from Ukraine[208]

- Cuban Revolutionary Air and Air Defense Force – 4 MiG-29s in inventory as of January 2014[200]

- Eritrean Air Force – 4 MiG-29s in service as of January 2014[200]

- Indian Air Force – 67 MiG-29s in service as of January 2021.[209]

- Indian Naval Air Arm – 44 MiG-29Ks in service as of February 2021[209]

- Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force – 44 MiG-29s in inventory as of 2012[210]

- Kazakh Air and Air Defence Forces – 12 MiG-29 and 2 MiG-29UB as of 2016[211]

- Mongolian Air Force - 6 MiG-29UBs in service as of December 2021.[212]

- Myanmar Air Force – 31 MiG-29s(6 SE, 20 SM(mod) and 5 UB) in January 2015[213] 10 are upgraded to MiG-29SM(mod) standard.[214]

- Korean People's Air Force – 18 MiG-29s (6 9.12B, 3 S-13 and 2 UB) as of July 2023.[146]

- Peruvian Air Force – 19 MiG-29s in service as of February 2021[206]

- Polish Air Force – 22 MiG-29s and 6 MiG-29UB used for conversion training in service as of 2022.[206]

- Russian Aerospace Forces – 87,[215] 70 MiG-29/MiG-29UB, 15 MiG-29SMT and 2 MiG-29UBT in service as of 2022.[215]

- Russian Naval Aviation – 24 MiG-29Ks[206]

- Serbian Air Force and Air Defence – 14 MiG-29s (5 MiG-29Аs, 3 MiG-29Bs, 3 MiG-29Ss, 3 MiG-29UBs) in inventory as of 2022, 11 of which are modernized to the advanced MiG-29SMT standards while 3 (MiG-29UB) are used as a conversion trainer.[216]

- Sudanese Air Force – 11 in service as of January 2017[217]

- Syrian Arab Air Force – 20 in service with 12 more on order as of January 2017.[217] A new delivery in May 2020.[218]

- Turkmen Air Force – 24 MiG-29s in use as of January 2014[200]

- Ukrainian Air Force – 37-70 MiG-29s in use as of March 2019[219][220]

- Used by private defense contractor RAVN Aerospace for adversary training services.[221]

- Uzbekistan Air and Air Defence Forces – 60 MiG-29s in operation as of January 2014[200]

Former operators

Czechoslovakia – Received 18 MiG-29s and two MiG-29UB aircraft. Although six were capable of delivering nuclear weapons, the necessary equipment for this was removed as per the CFE treaty. All passed onto successor states.

Czechoslovakia – Received 18 MiG-29s and two MiG-29UB aircraft. Although six were capable of delivering nuclear weapons, the necessary equipment for this was removed as per the CFE treaty. All passed onto successor states. Czech Republic – Inherited nine MiG-29 and one MiG-29UB. All sold to Poland in 1995 in exchange for 11 W-3A Sokol helicopters. Replaced with Saab JAS 39 Gripen.

Czech Republic – Inherited nine MiG-29 and one MiG-29UB. All sold to Poland in 1995 in exchange for 11 W-3A Sokol helicopters. Replaced with Saab JAS 39 Gripen. East Germany – 24 absorbed into the West German Air Force upon reunification.

East Germany – 24 absorbed into the West German Air Force upon reunification. Germany – One crashed, one on display, 22 sold to Poland in 2003 for €22 ($26.02).[222]

Germany – One crashed, one on display, 22 sold to Poland in 2003 for €22 ($26.02).[222] Hungary – 28 in inventory as of January 2011.[223] Reportedly stored outside.[224] The last fighter was retired in December 2010,[225] at which point only 4 aircraft were still in operational condition.[224] In 2011 the Hungarian government intended to sell six MiG-29B and two MiG-29UB aircraft. Replaced with JAS 39 Gripen but kept in reserve if needed.[226] In October 2017, the Hungarian Air Force announced that 23 MiG-29s were to be auctioned off including engines and spare parts in November.[227] The online auction had a reservation price of €8.7 million and failed to attract any bidders. This might have been because of an agreement between Hungary and Russia requiring the manufacturer's (Russia's) approval to transfer ownership of the aircraft.[224]

Hungary – 28 in inventory as of January 2011.[223] Reportedly stored outside.[224] The last fighter was retired in December 2010,[225] at which point only 4 aircraft were still in operational condition.[224] In 2011 the Hungarian government intended to sell six MiG-29B and two MiG-29UB aircraft. Replaced with JAS 39 Gripen but kept in reserve if needed.[226] In October 2017, the Hungarian Air Force announced that 23 MiG-29s were to be auctioned off including engines and spare parts in November.[227] The online auction had a reservation price of €8.7 million and failed to attract any bidders. This might have been because of an agreement between Hungary and Russia requiring the manufacturer's (Russia's) approval to transfer ownership of the aircraft.[224].svg.png.webp) Iraq – Received 37 MiG-29s during Saddam Hussein's era; these were destroyed or written off and some were flown to Iran.

Iraq – Received 37 MiG-29s during Saddam Hussein's era; these were destroyed or written off and some were flown to Iran. Israel – Leased from Poland in 1997.[228][229]

Israel – Leased from Poland in 1997.[228][229] Malaysia – Malaysia retired 16 MiG-29s in 2017 for lack of spare parts and engine problem.[230][231][232]

Malaysia – Malaysia retired 16 MiG-29s in 2017 for lack of spare parts and engine problem.[230][231][232] Moldova – Not operational,[201] six MiG-29S in storage. In the 1990s, a total of six were sold to the US for type evaluation testing.[233][234]

Moldova – Not operational,[201] six MiG-29S in storage. In the 1990s, a total of six were sold to the US for type evaluation testing.[233][234] Romania – 17 MiG-29A and five MiG-29UB were delivered from 1989,[235] 1 MiG-29S received from Moldova in 1992.[236] Retired in 2003.

Romania – 17 MiG-29A and five MiG-29UB were delivered from 1989,[235] 1 MiG-29S received from Moldova in 1992.[236] Retired in 2003..svg.png.webp) Serbia and Montenegro – Inherited from Yugoslavia, six destroyed in 1999.[237]

Serbia and Montenegro – Inherited from Yugoslavia, six destroyed in 1999.[237]

.jpg.webp)

Slovakia – Slovakia operated in total 24 MiG-29s. 9 MiG-29A and 1 MiG-29UB were inherited from Czechoslovakia. From 1993 to 1995 Slovakia ordered 12 additional MiGs-29A and 2 MiG-29UB fighters as compensation for Russian debt.[238] 12 aircraft were upgraded by the Russian Aircraft Corporation MiG and Western companies in 2007 and 2008 to fulfill the NATO requirements,[239][240] and were maintained by Russian military technicians at Sliač Air Base.[241] They were officially withdrawn from service on 31 August 2022.[242] Slovakia's Foreign Minister Rastislav Káčer has said that his country is prepared to transfer their fleet of MiG-29s to Ukraine. He said: "We have not yet handed [Ukraine] the MiG-29s. But we are ready to do it. We are talking with our NATO partners about how to do it,” and such a package would involve “several thousand” missiles.[243][244] Slovakia transferred the first four of its MiG-29 fighter jets, from 13 to be sent to Ukraine on 24 March 2023.[245]

Slovakia – Slovakia operated in total 24 MiG-29s. 9 MiG-29A and 1 MiG-29UB were inherited from Czechoslovakia. From 1993 to 1995 Slovakia ordered 12 additional MiGs-29A and 2 MiG-29UB fighters as compensation for Russian debt.[238] 12 aircraft were upgraded by the Russian Aircraft Corporation MiG and Western companies in 2007 and 2008 to fulfill the NATO requirements,[239][240] and were maintained by Russian military technicians at Sliač Air Base.[241] They were officially withdrawn from service on 31 August 2022.[242] Slovakia's Foreign Minister Rastislav Káčer has said that his country is prepared to transfer their fleet of MiG-29s to Ukraine. He said: "We have not yet handed [Ukraine] the MiG-29s. But we are ready to do it. We are talking with our NATO partners about how to do it,” and such a package would involve “several thousand” missiles.[243][244] Slovakia transferred the first four of its MiG-29 fighter jets, from 13 to be sent to Ukraine on 24 March 2023.[245] South Yemen – Received between 6 and 12 MiG-29s from either Moldova and Russia, or Moldova only, in 1994.[246]

South Yemen – Received between 6 and 12 MiG-29s from either Moldova and Russia, or Moldova only, in 1994.[246] Soviet Union – Passed on to successor states.

Soviet Union – Passed on to successor states. Yemen – 24 in service as of January 2017.[217] All grounded because of civil war. Many were destroyed on the ground during the Saudi-led Operation Decisive Storm in 2015.[247]

Yemen – 24 in service as of January 2017.[217] All grounded because of civil war. Many were destroyed on the ground during the Saudi-led Operation Decisive Storm in 2015.[247].svg.png.webp) Yugoslavia – 14 MiG-29 and 2 MiG-29UB, passed on to Serbia and Montenegro.[237]

Yugoslavia – 14 MiG-29 and 2 MiG-29UB, passed on to Serbia and Montenegro.[237]

Aircraft on display

Czech Republic

- On display at the Prague Aviation Museum in Prague.[248]

Germany

- 29+03 – MiG-29G on display at the Luftwaffenmuseum der Bundeswehr in Berlin.[115] This airframe is the only remaining German MiG-29 in Germany. It was previously on display in Laage before being moved to the Luftwaffenmuseum der Bundeswehr in 2006 as part of the exhibition "50 Jahre Luftwaffe".[249][250]

Hungary

- One MiG-29B is on display with other older MiG planes and helicopters at The RepTár Museum of Szolnok, Hungary.[251]

India

- KB-732 – On display as a gate guardian at Ojhar Air Force Station in Nasik, Maharashtra.[252]

- KB-741 – On display at the Technical Type Training (TETTRA) School in Pune, Maharashtra.[252]

Latvia

- 9-52 – MiG-29UB on display at the Riga Aviation Museum in Riga. This airframe is the second MiG-29UB prototype. After 213 test flights around Moscow between 23 August 1982 and 10 April 1986, it was disassembled and parts of the wings and tails were re-used in prototype (9–16). The remains were shipped to Riga Military Aviation Engineers High School, and later handed over to the Riga Aviation Museum in 1994, where it is currently displayed.[253] The remains of this prototype is in a very bad condition, with open fuselage panels and a partly broken canopy.[254]

Poland

- MiG-29G on display at the Muzeum Wojska Polskiego in Warsaw.[255]

- MiG-29GT on display at the Polish Aviation Museum in Kraków. This aircraft was sold by Germany to Poland in 2002 and briefly served in the Polish Air Force.[256]

Romania

- 67 – On display at the National Museum of Romanian Aviation in Bucharest.[257]

Russia

.jpg.webp)

- On display at the Central Air Force Museum in Monino. Painted as "Blue 01".[258] This airframe is the first prototype MiG-29.[259]

- On display at the Central Air Force Museum in Monino. Painted as "Blue 03".[260]

- On display at the Central Air Force Museum in Monino. Painted as "Blue 70".[261]

- On display at the Central Air Force Museum in Monino. Painted as "Blue 51".[262]

- On display at the Central Air Force Museum in Monino. Painted as "Blue 18". This airframe is a MiG-29KVP.[263]

- 2960705560 – On display at the Museum of the Great Patriotic War in Moscow. Painted as "Blue 26".[264]

- On display at the Vadim Zadorozhny Technical Museum in Khimki. Painted as "Blue 04".[265]

- On display at the Central Armed Forces Museum in Moscow. Painted as "Red 02".[266]

Slovakia

- 8605 – MiG-29A on display in Museum of Aviation in Košice[267]

- 7501 – MiG-29A on display at Sliač Air Force Base in Sliač. Normally not accessible to public.

- 9308 – MiG-29A on display in Vojenské historické múzeum Piešťany (Military History Museum Piešťany) in Piešťany.[268]

- 5817 – MiG-29A on display in Vojenské historické múzeum Piešťany[269]

- 5515 – MiG-29A on display in Vojenské historické múzeum Piešťany.[270]

United States

.jpg.webp)

- On display at Goodfellow Air Force Base in San Angelo, Texas.[271]

- On display at the airpark at Naval Air Station Fallon near Fallon, Nevada.[272]

- On display at the Threat Training Facility at Nellis Air Force Base near North Las Vegas, Nevada.[273][274]

- 2960516761 – MiG-29A on display in the Cold War Gallery of the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.[275]

- 2960516766 – On display at the Pima Air and Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona.[276][277]

- On display at the Evergreen Aviation and Space Museum in McMinnville, Oregon.[278]

- 50903012038 – MiG-29UB on display at the National Air and Space Intelligence Center at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.[277][279]

Airworthy

- N29UB – MiG-29UB owned by Jared Isaacman.[280] It was previously owned by the Flying Heritage Collection in Everett, Washington. The aircraft was obtained from Eastern Europe in early 2009. The aircraft has an FAA approved maintenance program and is flyable.[281]

- N129XX[282] – MiG-29UB owned by Air USA and located at the Quincy Regional Airport in Quincy, Illinois. This aircraft was purchased by Don Kirlin from Kyrgyzstan.[283] It is available for contract training and flight testing.[284]

- Two MiG-29UBs in flying condition were offered for sale from Eastern Europe in spring 2009. These aircraft come from the same source as the flyable aircraft owned by the Historic Flight Foundation.[285]

Specifications (MiG-29)

Data from Mikoyan,[286] airforce-technology.com,[287] deagel.com,[288] Business World[289]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 17.32 m (56 ft 10 in)

- Wingspan: 11.36 m (37 ft 3 in)

- Height: 4.73 m (15 ft 6 in)

- Wing area: 38 m2 (410 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 11,000 kg (24,251 lb)

- Gross weight: 14,900 kg (32,849 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 18,000 kg (39,683 lb)

- Fuel capacity: 3,500 kg (7,716 lb) internal

- Powerplant: 2 × Klimov RD-33 afterburning turbofan engines, 49.42 kN (11,110 lbf) thrust each [290] dry, 81.58 kN (18,340 lbf) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 2,450 km/h (1,520 mph, 1,320 kn) at high altitude

- Maximum speed: Mach 2.3+

- Range: 1,430 km (890 mi, 770 nmi) with maximum internal fuel[291]

- Combat range: 700–900 km (430–560 mi, 380–490 nmi) with 2 x R-27s, 4 x R-73s at high altitude[292]

- Ferry range: 2,100 km (1,300 mi, 1,100 nmi) with 1× drop tank

- Service ceiling: 18,000 m (59,000 ft)

- g limits: +9

- Rate of climb: 330 m/s (65,000 ft/min) [293]

- Wing loading: 403 kg/m2 (83 lb/sq ft)

- Thrust/weight: 1.09

Armament

- Guns: 1 × 30 mm Gryazev-Shipunov GSh-30-1 autocannon. Originally held 150 rounds, reduced to 100 on later variants.

- Hardpoints: 7 × hardpoints (6 × underwing, 1 × fuselage) with a capacity of up to 4,000 kg (8,800 lb) of stores, with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Rockets: *** S-5

- Missiles: *** 2 × R-27R/ER/T/ET/P air-to-air missiles

- 4 × R-60 AAMs

- 4 × R-73 AAMs

- 4 × Astra (Indian Air Force)

- AGM-88 HARM (Integration by Ukrainian Air Force during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine)[294][295]

- 4-6 × R-77 (MiG-29S, MiG-29M/M2 & MiG-29K only)

- Bombs: *** 6 × 665 kg (1,466 lb) bombs

Avionics

Notable appearances in media

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- AIDC F-CK-1 Ching-kuo

- Dassault Mirage 2000

- General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon

- McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet

Related lists

References

Notes

- "The MiG-29 fighters family". Archived 19 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Russian Aircraft Corporation MiG, 8 December 2014. Retrieved: 19 September 2018.

- Gordon and Davison 2005, p. 9.

- "Scramble". scramble.nl. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Jenkins 1998, pp. 9–11.

- Spick 2000, pp. 488–489, 512–513.

- Gordon and Davison 2005, pp. 8–9.

- Correll, John T. "The Reformers." Air Force Magazine Online, February 2008, pp. 7–9. Archived 26 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Lake World Air Power Journal Volume 36 Spring 1999, pp. 110–111.

- Lambert 1993, p. 238.

- Zuyev, A. and Malcolm McConnell. Fulcrum: A Top Gun Pilot's Escape from the Soviet Empire. Clayton, Victoria, Australia: Warner Books, 1993. ISBN 0-446-36498-3.

- Gordon and Davison 2005, pp. 27–29.

- Eden 2004, pp. 310–321.