Microchannel plate detector

A microchannel plate (MCP) is used to detect single particles (electrons, ions and neutrons[1]) and photons (ultraviolet radiation and X-rays). It is closely related to an electron multiplier, as both intensify single particles or photons by the multiplication of electrons via secondary emission.[2] Because a microchannel plate detector has many separate channels, it can provide spatial resolution.

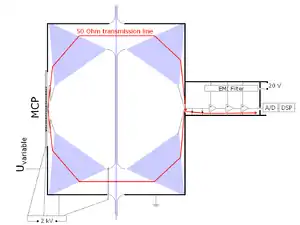

Schematic diagram of the operation of a microchannel plate | |

| Related items | Daly detector Electron multiplier |

|---|---|

Basic design

A microchannel plate is a slab made from resistive material (most often glass) 0.5 to 2mm thick with a regular array of tiny tubes (microchannels) leading from one face to the other. The microchannels are typically 5-20 micrometers in diameter, parallel to each other and enter the plate at a small angle to the surface (8-13° from normal). Plates are often round disks, but can be cut to any shape from sizes 10mm up to 200mm. They may also be curved.

Operating mode

At non-relativistic energies, single particles generally produce effects too small to enable their direct detection. The microchannel plate functions as a particle amplifier, turning a single impinging particle into a cloud of electrons. By applying a strong electric field across the MCP, each individual microchannel becomes a continuous-dynode electron multiplier.

A particle or photon that enters one of the channels through a small orifice is guaranteed to hit the wall of the channel, due to the channel being at an angle to the plate. The impact starts a cascade of electrons that propagates through the channel, amplifying the original signal by several orders of magnitude, depending on the electric field strength and the geometry of the microchannel plate. After the cascade, the microchannel takes time to recover (or recharge) before it can detect another signal.

The electrons exit the channels on the opposite side of the plate, where they are collected on an anode. Some anodes are designed to allow spatially resolved ion collection, producing an image of the particles or photons incident on the plate.

Although in many cases the collecting anode functions as the detecting element, the MCP itself can also be used as a detector. The discharging and recharging of the plate produced by the electron cascade, can be decoupled from the high voltage applied to the plate and measured, to directly produce a signal corresponding to a single particle or photon.

The gain of an MCP is very noisy, meaning that two identical particles detected in succession will often produce wildly different signal magnitudes. The temporal jitter resulting from the peak height variation can be removed by using a constant fraction discriminator. Thusly employed, MCPs are capable of measuring particle arrival times with high resolution, making them ideal detectors for mass spectrometers.

Chevron MCP

Most modern MCP detectors consist of two microchannel plates with angled channels, rotated 180° from each other - producing a shallow chevron (v-like) shape. In a chevron MCP, the electrons that exit the first plate start the cascade in the next plate. The angle between the channels reduces ion feedback in the device, as well as producing significantly more gain at a given voltage, compared to a straight channel MCP. The two MCPs can either be pressed together to preserve spatial resolution, or have a small gap between them to spread the charge across multiple channels, which further increases the gain.

Z stack MCP

This is an assembly of three microchannel plates with channels aligned in a Z shape. Single MCPs can have gain up to 10,000 (40dB) but this system can provide gain more than 10 million (70dB).[3]

The detector

An external voltage divider is used to apply 100 volts to the acceleration optics (for electron detection), each MCP, the gap between the MCPs, the backside of the last MCP, and the collector (anode). The last voltage dictates the time of flight of the electrons and in this way, the pulse-width.

The anode is a 0.4 mm thick plate with an edge of 0.2 mm radius to avoid high field strengths. It is just large enough to cover the active area of the MCP, because the backside of the last MCP, and the anode, together act as a capacitor with 2 mm separation - and large capacitance slows down the signal. The positive charge in the MCP influences positive charge in the backside metalization. A hollow torus conducts this around the edge of the anode plate. A torus is the optimum compromise between low capacitance and short path and for similar reasons, usually no dielectric (Markor) is placed into this region. After a 90° turn of the torus it is possible to attach a large coaxial waveguide. A taper permits minimizing the radius so that an SMA connector can be used. To save space and make the impedance match less critical, the taper is often reduced to a small 45° cone on the backside of the anode plate.

The typical 500 volts between the backside of the last MCP and the anode cannot be fed directly into the preamplifier; the inner or the outer conductor needs a DC block, that is, a capacitor. Often it is chosen to only have 10-fold capacitance compared to the MCP-anode capacitance and is implemented as a plate capacitor. Rounded, electro-polished metal plates and the ultra high vacuum allow very high field strengths and high capacitance without a dielectric. The bias for the center conductor is applied via resistors hanging through the waveguide (see bias tee). If the DC block is used in the outer conductor, it is aligned in parallel with the larger capacitor in the power supply. Assuming good screening, the only noise is due to current noise from the linear power regulator. Because the current is low in this application and space for large capacitors is available, and because the DC-block capacitor is fast, it is possible to have very low voltage noise, so that even weak MCP signals can be detected. Sometimes the preamplifier is on a potential (off ground) and gets its power through a low-power isolation transformer and outputs its signal optically.

The gain of an MCP is very noisy, especially for single particles. With two thick MCPs (>1 mm) and small channels (< 10 µm), saturation occurs, especially at the ends of the channels after many electron multiplications have taken place. The last stages of the following semiconductor amplifier chain also go into saturation. A pulse of varying length, but stable height and a low jitter leading edge is sent to the time to digital converter. The jitter can be further reduced by means of a constant fraction discriminator. That means that the MCP and the preamplifier are used in the linear region (space charge negligible) and the pulse shape is assumed to be due to an impulse response, with variable height but fixed shape, from a single particle.

Because MCPs have a fixed charge that they can amplify in their life, the second MCP especially, has a lifetime problem.[4] It is important to use thin MCPs, low voltage and instead of greater voltage, more sensitive and fast semiconductor amplifiers after the anode. (see: Secondary emission#Special amplifying tubes,[5][6][7]).

With high count rates or slow detectors (MCPs with phosphor screen or discrete photomultipliers), pulses overlap. In this case, a high impedance (slow, but less noisy) amplifier and an ADC are used. Since the output signal from the MCP is generally small, the presence of the thermal noise limits the measurement of the time structure of the MCP signal. With fast amplification schemes, however, it is possible to have valuable information on the signal amplitude even at very low signal levels, yet not on the time structure information of the wideband signals.

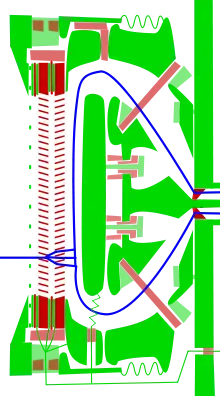

Delay line detector

In a delay line detector the electrons are accelerated to 500 eV between the back of the last MCP and a grid. They then fly for 5 mm and are dispersed over an area of 2 mm. A grid follows. Each element has a diameter of 1 mm and consists of an electrostatic lens focusing arriving electrons through a 30 µm hole of a grounded sheet of aluminium. Behind that, a cylinder of the same size follows. The electron cloud induces a 300 ps negative pulse when entering the cylinder and a positive when leaving. After that another sheet, a second cylinder follows, and a last sheet follows. Effectively the cylinders are fused into the center-conductor of a stripline. The sheets minimize cross talk between the layers and adjacent lines in the same layer, which would lead to signal dispersion and ringing. These striplines meander across the anode to connect all cylinders, to offer each cylinder 50 Ω impedance, and to generate a position dependent delay. Because the turns in the stripline adversely affect the signal quality their number is limited and for higher resolutions multiple independent striplines are needed. At both ends the meanders are connected to detector electronics. These electronics convert the measured delays into X- (first layer) and Y-coordinates (second layer). Sometimes a hexagonal grid and 3 coordinates are used. This redundancy reduces the dead space-time by reducing the maximum travel distance and thus the maximum delay, allowing for faster measurements. The microchannel plate detector must not operate over around 60 degree Celsius, otherwise it will degrade rapidly, bakeout without voltage has no influence.

Examples of use

- The mass-market application of microchannel plates is in image intensifier tubes of night vision goggles, which amplify visible and invisible light to make dark surroundings visible to the human eye.

- A 1 GHz real-time display CRT for an analog oscilloscope (the Tektronix 7104) used a microchannel plate placed behind the phosphor screen to intensify the image. Without the plate, the image would be excessively dim, because of the electron-optical design.

- MCP detectors are often employed in instrumentation for physical research, and they can be found in devices such as electron and mass spectrometers.

See also

References

- Tremsin, A.S.; McPhate, J.B.; Steuwer, A.; Kockelmann, W.; Paradowska, A.M.; Kelleher, J.F.; Vallerga, J.V.; Siegmund, O.H.W.; Feller, W.B. (28 September 2011). "High-Resolution Strain Mapping Through Time-of-Flight Neutron Transmission Diffraction with a Microchannel Plate Neutron Counting Detector". Strain. 48 (4): 296–305. doi:10.1111/j.1475-1305.2011.00823.x. S2CID 136775629.

- Wiza, J. (1979). "Microchannel plate detectors". Nuclear Instruments and Methods. 162 (1–3): 587–601. Bibcode:1979NucIM.162..587L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.119.933. doi:10.1016/0029-554X(79)90734-1.

- Wolfgang Göpel; Joachim Hesse; J. N. Zemel (2008-09-26). Sensors, Optical Sensors. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 260–. ISBN 978-3-527-26772-9.

- S-O Flyckt and C. Marmonier, Photomultiplier Tubes — Principles and Applications. Photonis, Brive, France, 2002, page 1-20.

- http://www.physics.utah.edu/~sommers/hybrid/correspondence/gemmeke.y98m11d09

- Internet Archive Wayback Machine

- Matsuura, S.; Umebayashi, S.; Okuyama, C.; Oba, K. (1985). "Characteristics of the newly developed MCP and its assembly". IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science. 32 (1): 350–354. Bibcode:1985ITNS...32..350M. doi:10.1109/TNS.1985.4336854. S2CID 37395966.

Bibliography

- Westmacott, G.; Frank, M.; Labov, S. E.; Benner, W. H. (2000). "Using a superconducting tunnel junction detector to measure the secondary electron emission efficiency for a microchannel plate detector bombarded by large molecular ions". Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 14 (19): 1854–1861. Bibcode:2000RCMS...14.1854W. doi:10.1002/1097-0231(20001015)14:19<1854::AID-RCM102>3.0.CO;2-M. PMID 11006596.

- Gaire, B.; Sayler, A. M.; Wang, P. Q.; Johnson, N. G.; Leonard, M.; Parke, E.; Carnes, K. D.; Ben-Itzhak, I. (2007). "Determining the absolute efficiency of a delay line microchannel-plate detector using molecular dissociation". Review of Scientific Instruments. 78 (2): 024503–024503–5. Bibcode:2007RScI...78b4503G. doi:10.1063/1.2671497. PMID 17578132.

- Richards, P.; Lees, J. (2002). "Functional proteomics using microchannel plate detectors". Proteomics. 2 (3): 256–261. doi:10.1002/1615-9861(200203)2:3<256::AID-PROT256>3.0.CO;2-K. PMID 11921441. S2CID 44466566.

- Michael Lampton (November 1, 1981). "The Microchannel Image Intensifier". Scientific American. 245 (5): 62–71. Bibcode:1981SciAm.245e..62L. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1181-62.

- U.S. Patent 5,565,729

- U.S. Patent 5,265,327

- U.S. Patent 7,420,147

- U.S. Patent 3,979,621

- U.S. Patent 4,153,855

- U.S. Patent 7,990,032

- U.S. Patent 4,780,395