Microexpression

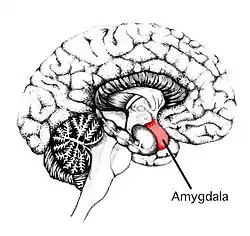

A microexpression is a facial expression that only lasts for a short moment. It is the innate result of a voluntary and an involuntary emotional response occurring simultaneously and conflicting with one another, and occurs when the amygdala responds appropriately to the stimuli that the individual experiences and the individual wishes to conceal this specific emotion. This results in the individual very briefly displaying their true emotions followed by a false emotional reaction.[1]

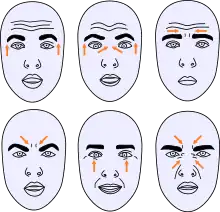

Human emotions are an unconscious biopsychosocial reaction that derives from the amygdala and they typically last 0.5–4.0 seconds,[1] although a microexpression will typically last less than 1/2 of a second.[2] Unlike regular facial expressions it is either very difficult or virtually impossible to hide microexpression reactions. Microexpressions cannot be controlled as they happen in a fraction of a second, but it is possible to capture someone's expressions with a high speed camera and replay them at much slower speeds.[3] Microexpressions express the seven universal emotions: disgust, anger, fear, sadness, happiness, contempt, and surprise. Nevertheless, in the 1990s, Paul Ekman expanded his list of emotions, including a range of positive and negative emotions not all of which are encoded in facial muscles. These emotions are amusement, embarrassment, anxiety, guilt, pride, relief, contentment, pleasure, and shame.[4][5]

History

Microexpressions were first discovered by Haggard and Isaacs. In their 1966 study, Haggard and Isaacs outlined how they discovered these "micromomentary" expressions while "scanning motion picture films of psychotherapy for hours, searching for indications of non-verbal communication between therapist and patient"[6] Through a series of studies, Paul Ekman found a high agreement across members of diverse Western and Eastern literate cultures on selecting emotional labels that fit facial expressions. Expressions he found to be universal included those indicating anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. Findings on contempt are less clear, though there is at least some preliminary evidence that this emotion and its expression are universally recognized.[7] Working with his long-time friend Wallace V. Friesen, Ekman demonstrated that the findings extended to preliterate Fore tribesmen in Papua New Guinea, whose members could not have learned the meaning of expressions from exposure to media depictions of emotion.[8] Ekman and Friesen then demonstrated that certain emotions were exhibited with very specific display rules, culture-specific prescriptions about who can show which emotions to whom and when. These display rules could explain how cultural differences may conceal the universal effect of expression.[9]

In the 1960s, William S. Condon pioneered the study of interactions at the fraction-of-a-second level. In his famous research project, he scrutinized a four-and-a-half-second film segment frame by frame, where each frame represented 1/25th second. After studying this film segment for a year and a half, he discerned interactional micromovements, such as the wife moving her shoulder exactly as the husband's hands came up, which combined yielded rhythms at the micro level.[10]

Years after Condon's study, American psychologist John Gottman began video-recording living relationships to study how couples interact. By studying participants' facial expressions, Gottman was able to correlate expressions with which relationships would last and which would not.[11] Gottman's 2002 paper makes no claims to accuracy in terms of binary classification, and is instead a regression analysis of a two factor model where skin conductance levels and oral history narratives encodings are the only two statistically significant variables. Facial expressions using Ekman's encoding scheme were not statistically significant.[12] In Malcolm Gladwell's book Blink, Gottman states that there are four major emotional reactions that are destructive to a marriage: defensiveness which is described as a reaction toward a stimulus as if you were being attacked, stonewalling which is the behavior where a person refuses to communicate or cooperate with another,[13] criticism which is the practice of judging the merits and faults of a person, and contempt which is a general attitude that is a mixture of the primary emotions disgust and anger.[14] Among these four, Gottman considers contempt the most important of them all.[15]

Types

Microexpressions are typically classified based on how an expression is modified. They exist in three groups:

- Simulated expressions: when a microexpression is not accompanied by a genuine emotion. This is the most commonly studied form of microexpression because of its nature. It occurs when there is a brief flash of an expression, and then returns to a neutral state.[16]

- Neutralized expressions: when a genuine expression is suppressed and the face remains neutral. This type of micro-expression is not observable due to the successful suppression of it by a person.[16]

- Masked expressions: when a genuine expression is completely masked by a falsified expression. Masked expressions are microexpressions that are intended to be hidden, either subconsciously or consciously.[17]

In photographs and films

Microexpressions can be difficult to recognize, but still images and video can make them easier to perceive. In order to learn how to recognize the way that various emotions register across parts of the face, Ekman and Friesen recommend the study of what they call "facial blueprint photographs", photographic studies of "the same person showing all the emotions" under consistent photographic conditions.[18] However, because of their extremely short duration, by definition, microexpressions can happen too quickly to capture with traditional photography. Both Condon and Gottman compiled their seminal research by intensively reviewing film footage. Frame rate manipulation also allows the viewer to distinguish distinct emotions, as well as their stages and progressions, which would otherwise be too subtle to identify. This technique is demonstrated in the short film Thought Moments by Michael Simon Toon and a film in Malayalam Pretham 2016[19][20][21] Paul Ekman also has materials he has created on his website that teach people how to identify microexpressions using various photographs, including photos he took during his research period in New Guinea.[22]

Moods vs emotions

Moods differ from emotions in that the feelings involved last over a longer period. For example, a feeling of anger lasting for just a few minutes, or even for an hour, is called an emotion. But if the person remains angry all day, or becomes angry a dozen times during that day, or is angry for days, then it is a mood.[23] Many people describe this as a person being irritable, or that the person is in an angry mood. As Paul Ekman described, it is possible but unlikely for a person in this mood to show a complete anger facial expression. More often just a trace of that angry facial expression may be held over a considerable period: a tightened jaw or tensed lower eyelid, or lip pressed against lip, or brows drawn down and together.[24] Emotions are defined as a complex pattern of changes, including physiological arousal, feelings, cognitive processes, and behavioral reactions, made in response to a situation perceived to be personally significant.[25]

Controlled microexpressions

Facial expressions are not just uncontrolled instances. Some may in fact be voluntary and others involuntary, and thus some may be truthful and others false or misleading.[26] Facial expression may be controlled or uncontrolled. Some people are born able to control their expressions (such as pathological liars), while others are trained, for example actors. "Natural liars" may be aware of their ability to control microexpressions, and so may those who know them well; they may have been "getting away" with things since childhood due to greater ease in fooling their parents, teachers, and friends.[27] People can simulate emotion expressions, attempting to create the impression that they feel an emotion when they are not experiencing it at all. A person may show an expression that looks like fear when in fact they feel nothing, or perhaps some other emotion.[28] Facial expressions of emotion are controlled for various reasons, whether cultural or by social conventions. For example, in the United States many little boys learn the cultural display rule, "little men do not cry or look afraid". There are also more personal display rules, not learned by most people within a culture, but the product of the idiosyncrasies of a particular family. A child may be taught never to look angrily at his father, or never to show sadness when disappointed. These display rules, whether cultural ones shared by most people or personal, individual ones, are usually so well-learned, and learned so early, that the control of the facial expression they dictate is done automatically without thinking or awareness.[29]

Emotional intelligence

Involuntary facial expressions can be hard to pick up and understand explicitly, and it is more of an implicit competence of the unconscious mind. Daniel Goleman created a conclusion on the capacity of an individual to recognize their own, as well as others' emotions, and to discriminate emotions based on introspection of those feelings. This is part of Goleman's emotional intelligence. In E.I, attunement is an unconscious synchrony that guides empathy. Attunement relies heavily on nonverbal communication.[30] Looping is where facial expressions can elicit involuntary behavior. In the research motor mimicry there shows neurons that pick up on facial expressions and communicate with motor neurons responsible for muscles in the face to display the same facial expression. Thus displaying a smile may elicit a micro expression of a smile on someone who is trying to remain neutral in their expression.[31]

Through fMRI we can see the area where these Mirror neurons are located lights up when you show the subject an image of a face expressing an emotion using a mirror. In the relationship of the prefrontal cortex also known as the (executive mind) which is where cognitive thinking experience and the amygdala being part of the limbic system is responsible for involuntary functions, habits, and emotions. The amygdala can hijack the pre-frontal cortex in a sympathetic response. In his book Emotional Intelligence Goleman uses the case of Jason Haffizulla (who assaulted his high school physics teacher because of a grade he received on a test) as an example of an emotional hijacking in which rationality and better judgement can be impaired.[30] This is one example of how the bottom brain can interpret sensory memory and execute involuntary behavior. This is the purpose of microexpressions in attunement and how you can interpret the emotion that is shown in a fraction of a second. The microexpression of a concealed emotion that's displayed to an individual will elicit the same emotion in them to a degree, this process is referred to as an emotional contagion.[31]

MFETT and SFETT

Micro Facial expression training tools and subtle Facial expression training tools are software made to develop someone's skills in the competence of recognizing emotion. The software consists of a set of videos that you watch after being educated on the facial expressions. After watching a short clip, there is a test of your analysis of the video with immediate feedback. This tool is to be used daily to produce improvements. Individuals that are exposed to the test for the first time usually do poor trying to assume what expression was presented, but the idea is through the reinforcement of the feedback you unconsciously generate the correct expectations of that expression. These tools are used to develop rounder social skills and a better capacity for empathy. They are also quite useful for development of social skills in people on the autism spectrum.[31] Lie detection is an important skill not only in social situations and in the workplace, but also for law enforcement and other occupations that deal with frequent acts of deception. Microexpression and subtle expression recognition are valuable assets for these occupations as it increases the chance of detecting deception. In recent years it was found that the average person has a 54% accuracy rate in terms of exposing whether a person is lying or being truthful.[32] However, Ekman had done a research experiment and discovered that secret service agents have a 64% accuracy rate. In later years, Ekman found groups of people that are intrigued by this form of detecting deception and had accuracy rates that ranged from 68% to 73%. Their conclusion was that people with the same training on microexpression and subtle expression recognition will vary depending on their level of emotional intelligence.[32]

Lies and leakage

The sympathetic nervous system is one of two divisions under the autonomic nervous system, it functions involuntarily and one aspect of the system deals with emotional arousal in response to situations accordingly.[33] Therefore, if an individual decides to deceive someone, they will experience a stress response within because of the possible consequences if caught. A person using deception will typically cope by using nonverbal cues which take the form of bodily movements. These bodily movements occur because of the need to release the chemical buildup of cortisol, which is produced at a higher rate in a situation where there is something at stake.[34] The purpose for these involuntary nonverbal cues are to ease oneself in a stressful situation. In the midst of deceiving an individual, leakage can occur which is when nonverbal cues are exhibited and are contradictory to what the individual is conveying.[35] Despite this useful tactic of detecting deception, microexpressions do not show what intentions or thoughts the deceiver is trying to conceal. They only provide the fact that there was emotional arousal in the context of the situation. If an individual displays fear or surprise in the form of a microexpression, it does not mean that the individual is concealing information that is relevant to investigation. This is similar to how polygraphs fail to some degree: because there is a sympathetic response due to the fear of being disbelieved as innocent. The same goes for microexpressions, when there is a concealed emotion there is no information revealed on why that emotion was felt. They do not determine a lie, but are a form of detecting concealed information. David Matsumoto is a well-known American psychologist and explains that one must not conclude that someone is lying if a microexpression is detected but that there is more to the story than is being told.[36] Matsumoto was also the first to publish scientific evidence that microexpressions may be a key to detecting deception.[37]

Despite the prevailing belief among law enforcement and the public that micro-expressions are able to reveal whether a person is being deceitful,[38] there is a lack of empirical evidence to support this claim.[39][40] Research has shown that there is often a disconnect between displayed emotions and felt emotions; in short, deception does not necessarily produce negative emotions and negative emotions do not necessarily signal deception.[41] In addition, microexpressions do not occur often enough to be useful.[38] In one of the few studies of microexpressions, researchers found that only 2% of emotional expressions coded could be considered microexpressions and they appeared equally for truth-tellers and liars.[38][39] Other studies have found that liars and truth-tellers exhibit different responses than expected:[42][43] in a concealed information test, Pentland and colleagues found that liars showed less contempt and more intense smiles than truthful people.[43] This counters the fundamental idea behind microexpressions, which suggests that it is impossible for a liar to conceal their true nature, as evidence of their guilt "leaks" out through these expressions.[42][44] Taken together, their findings suggest that micro-expressions do not occur frequently enough to be detectable, neither are they consistent enough to distinguish liars from truth-tellers.

Universality

A significant amount of research has been done in respect to whether basic facial expressions are universal or are culturally distinct. After Charles Darwin had written The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals it was widely accepted that facial expressions of emotion are universal and biologically determined.[45] Many writers have disagreed with this statement. David Matsumoto however agreed with this statement in his study of sighted and blind Olympians. Using thousands of photographs captured at the 2004 Olympic and Paralympic Games, Matsumoto compared the facial expressions of sighted and blind judo athletes, including individuals who were born blind. All competitors displayed the same expressions in response to winning and losing.[46] Matsumoto discovered that both blind and sighted competitors displayed similar facial expression, during winnings and loss. These results suggest that our ability to modify our faces to fit the social setting is not learned visually.[46] Matsumoto also has training tools he has created on his website that teaches people how to identify micro and subtle facial expressions of emotion.[47]

In popular culture

Microexpressions and associated science are the central premise for the 2009 television series Lie to Me, based on discoveries of Paul Ekman. The main character uses his acute awareness of microexpressions and other body language clues to determine when someone is lying or hiding something.

They also play a central role in Robert Ludlum's posthumously published The Ambler Warning, in which the central character, Harrison Ambler, is an intelligence agent able to recognize them. Similarly, one of the main characters in Alastair Reynolds' science fiction novel, Absolution Gap, Aura, can easily read microexpressions.

In The Mentalist, the main character, Patrick Jane, can often tell when people are being dishonest. However, specific reference to microexpressions is only made once in the 7th and final season.

In the 2015 science fiction thriller Ex Machina, Ava, an artificially intelligent humanoid, surprises the protagonist, Caleb, in their first meeting, when she tells him "Your microexpressions are telegraphing discomfort."

Controversy

Though the study of microexpressions has gained popularity through popular media, studies show it lacks internal consistency in its conceptual formation.[48]

Maria Hartwig, professor of Psychology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, argues that it has led to wrongful imprisonment of suspects who were aggressively interrogated due to perceived micro expressions. [49]

A 2016 article in Nature explains that it is possible to mask involuntary expressions with fake expressions, and that in real world situations, over 40% of the time we can not tell the difference. [50]

Judee K. Burgoon argues in a 2018 Frontiers in Psychology opinion that micro expressions theory presumes that people feel detectible emotions always connected to the same thoughts or motivations. But what if, for example, people feel happy rather than guilty about deceiving others? [51] Burgoon also cites studies showing that micro-expressions are rare:

In one of the very few investigations of microexpression frequency, Porter and ten Brinke (2008) coded 700 high-stakes genuine and falsified emotional expressions and found only 2% were microexpressions.

and that they seldom result in arrests when implemented at places like airports:

testimony to the U.S. Congress revealed that only 0.6% out of 61,000 passenger referrals to law enforcement in 2011 and 2012 resulted in arrests (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2013)

See also

References

- Elena Svetieva; Mark G. Frank (April 2016). "Empathy, emotion dysregulation, and enhanced microexpression recognition ability". Motivation and Emotion. 40 (2): 309–320. doi:10.1007/s11031-015-9528-4. S2CID 146270791. ProQuest 1771277976.

- Hurley, Carolyn M; Anker, Ashley E; Frank, Mark G; Matsumoto, David; Hwang, Hyisung C. (Oct 2014). "Background factors predicting accuracy and improvement in micro expression recognition". Motivation and Emotion. 38 (5): 700–714. doi:10.1007/s11031-014-9410-9. S2CID 91178436. ProQuest 1555933143.

- Polikovsky, S.; Kameda, Y.; Ohta, Y. (2009). "Facial micro-expressions recognition using high speed camera and 3D-gradient descriptor". 3rd International Conference on Imaging for Crime Detection and Prevention (ICDP 2009). pp. P16. doi:10.1049/ic.2009.0244. ISBN 978-1-84919-207-1. Retrieved 2022-03-02.

- Ekman, Paul (1999). "Basic Emotions". In T. Dalgleish; M. Power (eds.). Handbook of Cognition and Emotion. Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Ekman, Paul (1992). "Facial Expressions of Emotion: An Old Controversy and New Findings". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. London. B335 (1273): 63–69. doi:10.1098/rstb.1992.0008. PMID 1348139.

- Haggard, E. A., & Isaacs, K. S. (1966). Micro-momentary facial expressions as indicators of ego mechanisms in psychotherapy. In L. A. Gottschalk & A. H. Auerbach (Eds.), Methods of Research in Psychotherapy (pp. 154–165). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Matsumoto, David (1992). "More evidence for the universality of a contempt expression". Motivation and Emotion. 16 (4): 363–368. doi:10.1007/bf00992972. S2CID 143333167.

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. (1971). "Constants across cultures in the face and emotion" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 17 (2): 124–129. doi:10.1037/h0030377. PMID 5542557. S2CID 14013552. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-28. Retrieved 2015-02-28.

- Ekman, Paul (1989). H. Wagner & A Manstead (ed.). Handbook of social psychophysiology. Chichester, England: Wiley. pp. 143–164. Chapter: The argument and evidence about universals in facial expressions of emotion.

- Sound Film Analysis of Normal and Pathological Behavior Patterns, Condon, W.S.; Ogston, W.D., Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 143(4):338–347, October 1966.

- "Research FAQs". Gottman.com. The Gottman Institute. Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- Gottman, J.; Levenson, R.W. (2002). "A Two-Factor Model for Predicting When a Couple Will Divorce: Exploratory Analyses Using 14-Year Longitudinal Data". Family Process. 41 (1): 83–96. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.40102000083.x. PMID 11924092. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05.

- Webber, Elizabeth; Feinsilber, Mike (1999). Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of Allusions. Merriam-Webster. pp. 519–. ISBN 9780877796282. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- TenHouten, W.D. (2007). General Theory of Emotions and Social Life. Routledge.

- Gladwell, Malcolm (2005). Blink, Chapter 1, Section 3, The Importance of Contempt

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-16. Retrieved 2013-11-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Godavarthy, Sridhar (July 2010). Microexpression spotting in video using optical strain (MS thesis). University of South Florida. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Ekman, P. & Friesen, W.V. (2003). Unmasking the Face. Cambridge: Malor Books. p. 169

- Prof. Ragodí. "Trabajo Psicología de 1er Trimestre." El Bigote de Bernays. Blogspot. Updated 11-19-2009. Accessed 8-5-13. http://elbigotedebernays.blogspot.com/2009/11/trabajo-psicologia-1er-trimestre.html

- Braun, Roman. "Eye Catcher." Trinergy-NLP-Blog. Posted 10-27-2009. Accessed 8-5-13. "TRINERGY-NLP-BLOG » Eye Catcher". Archived from the original on 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2013-08-06.

- "Thought Moments." British Films Directory. British Council. Updated 12-1-2009. http://film.britishcouncil.org/thought-moments

- "Micro Expressions Training Tools".

- Ekman, P. & Friesen, W.V. (2003). Unmasking the Face. Cambridge: Malor Books. p. 12.

- Ekman, P. & Friesen, W..V. (2003). Unmasking the Face. Cambridge: Malor Books. pp. 12–13.

- "APA Dictionary of Psychology".

- Ekman, P. & Friesen, W.V. (2003). Unmasking the Face. Cambridge: Malor Books. p. 19.

- Ekman, P. (1991). Telling Lies Clues to deceit in the Marketplace, Politics, and Marriage. New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., p. 56.

- Ekman, P. & Friesen, W.V. (2003). Unmasking the Face. Cambridge: Malor Books. p. 20.

- Ekman, P. & Friesen, W.V. (2003). Unmasking the Face. Cambridge: Malor Books. pp. 20–21.

- Goleman, Daniel (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books.

- Goleman, Daniel (2006). Social intelligence: the new science of human relationships. New York: Bantam Books.

- "Detecting Deception from Emotional and Unemotional Cues" (Document). ProQuest 229223092.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help) - Boeree, George. "The Limbic System". webspace.ship.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- "Cortisol | Hormone Health Network". www.hormone.org. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- "Interpreting Nonverbal Communication for Use in Detecting Deception" (Document). ProQuest 859010149.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help) - Matsumoto, D. (2010, March 21). Dr. David Matsumoto: How to Tell a Lie with the Naked Eye. Retrieved from Spying for Lying: "Spying for Lying: Dr. David Matsumoto: How to Tell a Lie with the Naked Eye". Archived from the original on 2013-05-28. Retrieved 2012-11-23.

- Matsumoto, David; Hwang, Hyisung C. (2018). "Microexpressions Differentiate Truths From Lies About Future Malicious Intent". Frontiers in Psychology. 9: 2545. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02545. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 6305322. PMID 30618966.

- Porter, Stephen; ten Brinke, Leanne (May 2008). "Reading Between the Lies". Psychological Science. 19 (5): 508–514. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02116.x. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 18466413. S2CID 20775868.

- Porter, Stephen; Brinke, Leanne (February 2010). "The truth about lies: What works in detecting high-stakes deception?". Legal and Criminological Psychology. 15 (1): 57–75. doi:10.1348/135532509x433151. ISSN 1355-3259.

- Vrij, Aldert; Hartwig, Maria; Granhag, Pär Anders (2019-01-04). "Reading Lies: Nonverbal Communication and Deception". Annual Review of Psychology. 70 (1): 295–317. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103135. ISSN 0066-4308. PMID 30609913. S2CID 58562467.

- Hoque, Mohammed Ehsan; McDuff, Daniel J.; Picard, Rosalind W. (July 2012). "Exploring Temporal Patterns in Classifying Frustrated and Delighted Smiles". IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing. 3 (3): 323–334. doi:10.1109/T-AFFC.2012.11. hdl:1721.1/79899. ISSN 1949-3045. S2CID 1966996.

- Burgoon, Judee K. (2018). "Microexpressions Are Not the Best Way to Catch a Liar". Frontiers in Psychology. 9: 1672. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01672. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 6158306. PMID 30294288.

- Pentland, S. J., Burgoon, J. K., & Twyman, N. W. (2015). Face and Head Movement Analysis Using Automated Feature Extraction Software. Proceedings of the 48th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (2015, Koloa, Hawaii) Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS).

- Porter, Stephen; ten Brinke, Leanne; Wallace, Brendan (March 2012). "Secrets and Lies: Involuntary Leakage in Deceptive Facial Expressions as a Function of Emotional Intensity". Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 36 (1): 23–37. doi:10.1007/s10919-011-0120-7. ISSN 0191-5886. S2CID 28783661.

- Darwin, C. (1872). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. London: John Murray.

- Bible, E. (2009, January 7). Smiles and frowns are innate, not learned. Retrieved from San Francisco State University: http://www.sfsu.edu/news/2009/spring/1.html

- "Humintell Products". Humintell. David Matsumoto. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- Porter, Stephen; Ten Brinke, Leanne (2008). "Reading Between the Lies". Psychological Science. 19 (5): 508–514. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02116.x. PMID 18466413. S2CID 20775868.

- Hartwig, Maria (2022-03-13). "No, you can't really tell if someone is lying from their facial expressions". Salon. Retrieved 2023-01-12.

- Iwasaki, Miho; Noguchi, Yasuki (2016-02-26). "Hiding true emotions: micro-expressions in eyes retrospectively concealed by mouth movements". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 22049. doi:10.1038/srep22049. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4768101. PMID 26915796.

- Burgoon, Judee K. (20 September 2018). "Microexpressions Are Not the Best Way to Catch a Liar". Frontiers in Psychology. 9: 1672. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01672. PMC 6158306. PMID 30294288 – via Researchgate.

Further reading

- Matthew Hertenstein (2015). The Tell: The Little Clues That Reveal Big Truths about Who We Are. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465036592.

External links

- Lying Is Exposed By Microexpressions We Can't Control, Science Daily, May 2006

- The Naked Face

- Facial Expressions Test based on "The Micro Expression Training Tool"

- "A Look Tells All" in Scientific American Mind October 2006

- Microexpressions Complicate Face Reading, by Medical News Today August 2007

- Deception Detection, American Psychological Association