Mike Graham (wrestler)

Edward Michael Gossett[2] (September 22, 1951 – October 19, 2012), better known as Mike Graham, was an American professional wrestler who was the son of Eddie Graham.

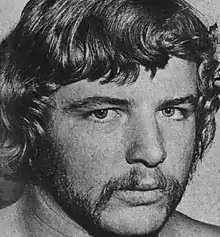

| Mike Graham | |

|---|---|

Graham, circa 1973 | |

| Birth name | Edward Michael Gossett |

| Born | September 22, 1951 Tampa, Florida, U.S. |

| Died | October 19, 2012 (aged 61) Daytona, Florida, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Multiple gunshot suicide |

| Family | Eddie Graham (father) |

| Professional wrestling career | |

| Ring name(s) | Mike Graham |

| Billed height | 5 ft 8 in (173 cm)[1] |

| Billed weight | 230 lb (104 kg)[1] |

| Trained by | Eddie Graham Yasuhiro Kojima Boris Malenko |

| Debut | 1972 |

| Retired | March 31, 2012 |

Amateur wrestling

Mike Graham was a Florida high school wrestling district champion his senior year in 1969 for Thomas Richard Robinson High School in Tampa, Florida.[3] He became a three-time state AAU champion[3][4] and a Junior Olympics champion at 198 pounds.[3] Graham was a state champion in the 154-pound weight class and, as a sophomore, defeated senior Richard Blood (later to become Ricky Steamboat) in the finals of a district meet.[4] He left the University of Tampa to turn professional against the wishes of his mother Lucy.[3][5] Mike was also an accomplished powerlifter who set state records in the bench press.[5]

Professional wrestling career

Michael Gossett started wrestling in 1972[6] in his father's Championship Wrestling from Florida, which was a National Wrestling Alliance territory.[7] He was trained by his father,[6] Boris Malenko and Hiro Matsuda.[6] He would often tag team with his father upon his arrival, but also formed a successful tag team with Kevin Sullivan.[7] Sullivan eventually turned on him to form his "Satanic cult", The Army of Darkness.[4] After getting turned on, Graham teamed with the likes of Steve Keirn and Barry Windham to feud with Sullivan's team and to capture several tag team titles over the years.[7][3] He was a mainstay on the Florida circuit during the ’70s and early 80’s and was a favorite of Gordon Solie and Dory Funk Jr.[4] He was also respected by Ric Flair, who noted "Mike Graham was as tough as they come, a phenomenal performer who never got the recognition he deserved because he was considered too small to be a championship contender. His reputation was legit for his size. He was very tough”. [4][5]

_and_David_Von_Erich%252C_1982.png.webp)

In 1981, Graham wrestled in the American Wrestling Association and feuded with Buck Zumhofe over the AWA Light Heavyweight Championship over the next two years.[7] Graham headed back to Florida in 1983, where he primarily worked as a singles wrestler. His father Eddie died after committing multiple gunshot suicide on January 21, 1985, leading to Mike taking over his Championship Wrestling from Florida territory.[3] In the late 1980s, he would again team with Keirn and wrestled in the NWA's Jim Crockett Promotions (who he sold his father's territory to), with Keirn briefly around this time.[3] He then went back to the AWA in 1988, where he won the Light Heavyweight Title again.[3] In the following years, Graham & Keirn wrestled in Memphis as a tag team, and Graham went back to Florida to the newly renamed Florida Championship Wrestling, where he briefly teamed with Dustin Rhodes.

Graham retired as an in-ring competitor in 1992.[7] He became a road agent for World Championship Wrestling. Along with the likes of Paul Orndorff, Pez Whatley and DeWayne Bruce, Graham also worked as a trainer in WCW as part of the WCW Power Plant.[7] At Slamboree 1993, Mike represented his deceased father when he was inducted into the WCW Hall of Fame. He was reportedly responsible for causing Chris Benoit, Eddie Guerrero, Dean Malenko, and Perry Saturn to leave the company for the WWF, granting their releases.[7] In the early 2000s, Graham was a road agent for the short-lived Xcitement Wrestling Federation and for Turnbuckle Championship Wrestling. Graham defeated his arch rival Kevin Sullivan at WrestleReunion 3 on September 10, 2005.[6] He made occasional appearances for the revived Florida Championship Wrestling. Mike Graham worked with World Wrestling Entertainment in early 2006, on a DVD about Dusty Rhodes, which was released on June 6, 2006. He made several appearances on WWE 24/7's Legends of Wrestling series as part of a panel which discussed famous pro wrestlers of the 1980s.[7] He also hosted classic episodes of Championship Wrestling from Florida on WWE 24/7 Classics.[7]

Graham's father was posthumously inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2008, with Mike representing him at the ceremony and the following night at WrestleMania XXIV.[6] Graham then competed in a Legends Battle Royal won by Roddy Piper for Pro Wrestling Guerrilla on January 29, 2011.[6] He also held a weekly radio show called Talking Wrestling with Mike Graham.[4] His former tag team partner Kevin Sullivan was the last ever guest in his radio show, recalling a chilling phone call where Mike was emotional and told Kevin he loved him; he killed himself six days later.[5]

Boat racing career

In addition to his wrestling career, Graham also competed in offshore power boat racing. In 1993, Graham throttled Kiely Motorsports' 35' Offshore Class C catamaran to multiple championship finishes:

- 1st Place Finish: Sarasota, Florida

- 1st Place Finish: Marathon, Florida

- 3rd Place Finish: New Orleans, Louisiana

- Reserve Championship: APBA / UIM Offshore World Championship in Sanibel Island, Florida.

Graham maintained position as the throttle man for each finish.

Death

On October 19, 2012, Graham was found dead by his wife of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head at their residence in Daytona Beach, Florida during Biketoberfest.[8] His father and son had committed suicide in similar manners on January 21, 1985, and December 14, 2010, (some sources state the 15th)[4] respectively.[8][7] He was 61 years old.[9] At the time of Mike’s death, he was wearing his son’s old work boots, and also frequently threatened committing suicide to his wife.[5] He was also intoxicated, and according to his toxicology report, Graham's blood-alcohol concentration was at 0.259.[9]

Graham suffered business misfortunes years prior to his death, and a restaurant he owned in Florida closed in 2011 after about two years of operation.[3] He and his wife were also involved in real estate, which took a beating in Florida during the recession.[7] His friends also claimed that he had struggled with the death of his son Steven.[7] He was also rejected by his daughter, blaming him for the deaths in some part for his mother and his son.[4] In the final months in his life, he had felt responsible for the deaths of his father and son.[9] A celebration of life for Graham was held in Largo, Florida, where nearly 500 people, including a number of retired professional wrestlers, attended.[4]

Championships and accomplishments

- American Wrestling Association

- Championship Wrestling from Florida

- FCW Tag Team Championship (2 times) - with Dustin Rhodes (1) and Joe Gomez (1)[6]

- NWA Florida Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[10]

- NWA Florida Global Tag Team Championship (1 time) - with Scott McGhee[6]

- NWA Florida Tag Team Championship (16 times) - with Kevin Sullivan (3), Eddie Graham (1), Ken Lucas (1), Steve Keirn (9), Ray Stevens (1), and Barry Windham (1)[6][5]

- NWA Florida Television Championship (2 times)[6]

- NWA International Junior Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[6]

- NWA North American Tag Team Championship (Florida version) (1 time) – with Steve Keirn[6]

- NWA United States Tag Team Championship (Florida version) (3 times) - with Steve Keirn[6]

- PWF Florida Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[6]

- Mid-South Sports

- NWA Mid-America

- Pro Wrestling Illustrated

- Southeastern Championship Wrestling

References

- "Wrestlingdata.com – The World's Largest Wrestling Database". WrestlingData.

- Callaway, J. D. (June 7, 1989). "Deputy's brawl with wrestler probed". The Tampa Tribune.

- Johnson, Steven (October 20, 2012). "Mike Graham dead at 61". Slam! Wrestling. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- Mooneyham, Mike (November 10, 2012). "Mike Graham suicide leaves family, friends searching for answers". The Post and Courier. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- Ojst, Javier (December 22, 2018). "Eddie and Mike Graham – Triumph and Dark Tragedy". Pro Wrestling Stories. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- "Mike Graham profile". Online World Of Wrestling. Retrieved April 18, 2008.

- Harris, Keith (October 22, 2012). "Mike Graham tragedy - commits suicide like father and son before him". Cageside Seats. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- Johnson, Mike (October 19, 2012). "CAUSE OF DEATH FOR MIKE GRAHAM, WWE ISSUES STATEMENT". PWInsider. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- Harris, Keith (November 20, 2012). "Mike Graham's autopsy reveals intoxication at the time of his suicide". Cageside Seats. Retrieved November 30, 2021.

- Hoops, Brian (January 15, 2019). "Pro wrestling history (01/15): Big John Studd wins 1989 Royal Rumble". Wrestling Observer Figure Four Online. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- "PWI Awards". Pro Wrestling Illustrated. Kappa Publishing Group. Archived from the original on January 4, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- Wrestling Information Archive - Pro Wrestling Illustrated's Top 500 Wrestlers of the PWI Years Retrieved on January 13, 2019

External links

- Mike Graham's profile at Cagematch.net , Internet Wrestling Database