Milan uprising (1311)

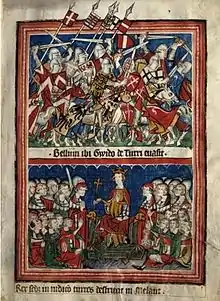

An uprising of the Guelph faction in Milan led by Guido della Torre (hence also known as the Torriani faction) on 12 February 1311 was crushed by the troops of King Henry VII on the same day.

Background

Henry had arrived in Milan some weeks earlier, on 23 December 1310,[2] and had been crowned King of Italy on 6 January 1311.[3] The Tuscan Guelphs refused to attend the ceremony, and began preparing for resistance. Henry also rehabilitated the Visconti, the ousted former rulers of Milan, who returned from exile. Guido della Torre, who had thrown the Visconti out of Milan, objected and organised a revolt against Henry.

Uprising

Around noon of 12 February, Duke Leopold of Austria, returning from a pleasure ride with few companions, was passing the Torriani quarter on his way back to his camp outside of Porta Comasina, northwest of the city, when he heard unusual noise of voices, weapons and horses, and through an open door he could see a congregation of men in full armour. Leopold sent his men back to his camp with the command to arm his followers, and went to king Henry, who was residing in the city palace, to warn him of the impending attack. Henry sent his brother Baldwin to fetch the German troops camped outside Porta Romana, southwest of the city, while a group of knights led by Henry of Flandres and John of Calcea rode to the Visconti palace and from there to the Torriani quarter, where they were immediately engaged in heavy combat. Henry remained in the palace, and ordered the palace gates to be barricaded, just in time before the arrival of an armed mob.

At the same time, the contingent of Teutonic Knights arrived, and in a single charge killed or dispersed most of the rebels. The German chronicles are unanimous in praising the bravery and valour of the knights in this attack, and especially their leader, the commander of Franconia and later Deutschmeister Konrad von Gundelfingen. The Austrian reinforcements had been delayed by barricades erected by the rebels at Porta Comasina. The Visconti reinforcement likewise arrived suspiciously late, in what was afterwards taken to imply at least passive support of the uprising. When the reinforcements arrived in the Torriani quarter, the fight there was mostly over. The soldiers now went on to loot the Torriani residences in a massacre that continued until nightfall.[1]

Aftermath

Guido della Torre escaped, and was condemned to death in absence by Henry. Archbishop Cassone della Torre was exiled. Matteo I Visconti was also accused of supporting the uprising, mostly by his enemy John of Cermenate. Unlike Guido della Torre and his sons, who had escaped the city, Matteo Visconti appeared before Henry to receive judgement. The fact that his son Galeazzo had supported Leopold against the rebels counted in Matteo's favour. Both Matteo and Galeazzo were still briefly exiled from the city, suggesting that Henry was not fully convinced of their loyalty.

The Visconti were soon returned to power, however, with Henry appointing Matteo I Visconti as the Imperial vicar of Milan.[3] He also imposed his brother-in-law, Amadeus of Savoy, as the vicar-general in Lombardy. Wernher von Homberg was given the title of lieutenant general of Lombardy, and was given the right to collect the imperial tax at Flüelen.

In the aftermath of the uprising, the Guelph cities of Northern Italy were turned against Henry, resisting the enforcement of his imperial claims on what had become communal lands and rights, and attempted to replace communal regulations with imperial laws.[4] Nevertheless, Henry managed to restore some semblance of imperial power in parts of northern Italy. Cities such as Parma, Lodi, Verona and Padua all accepted his rule.[3]

Historiography

While German chronicles (such as Codex Balduini and Gesta Treverorum) emphasise the valour of the German knights in the fight against the rebels,[1] Milanese historiography tended to depict the reprisals as the Germans unexpectedly assaulting the Torriani in their own homes.[5] An 1895 drawing by Lodovico Pogliaghi with the title "Assault on the houses of the Torriani in Milan" (assalto alle case dei Torriani a Milano, nel 1311) was included in Francesco Bertolini's Storia d'Italia. The Torriani houses damaged or destroyed by the Germans gave rise to the name case rotte ("broken houses") of that part of the city (modern Via Case Rotte, 45.4669°N 9.1909°E).

References

- Georg Irmer, Die Romfahrt Kaiser Heinrich's VII im Bildercyclus des Codex Balduini Trevirensis (1881), 43–46.

- Barthold (1830), p. 437.

- Jones, Michael, The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. VI: c. 1300-c. 1415, Cambridge University Press, 2000, 533f.

- Christopher Kleinhenz, Medieval Italy: an encyclopedia, Volume 1, Routledge, 2004, p. 495.

- "I Torriani sono inaspettatamento assaliti dalle truppe Tedesche nelle proprie case, e scacciati per sempre da Milano" Francesco Pirevano, Nuova Guida di Milano (1822), 26f.