Minor Pillar Edicts

The Minor Pillar Edicts of Indian Emperor Ashoka refer to 5 separate minor Edicts of Ashoka inscribed on columns, the Pillars of Ashoka, which are among the earliest dated inscriptions of any Indian monarch. A full English translation of the Edicts was published by Romila Thapar.[1]

| Minor Pillar Edicts of Ashoka | |

|---|---|

Minor Pillar Edict on the Sarnath pillar. | |

| Material | Sandstone |

| Created | 3rd century BCE |

| Present location | India, Afghanistan |

| Part of a series on the |

| Edicts of Ashoka |

|---|

These edicts are preceded chronologically by the Minor Rock Edicts and may have been made in parallel with the Major Rock Edicts. The inscription technique is generally poor compared for example to the later Major Pillar Edicts, however they are often associated with some of the artistically most sophisticated pillar capitals of Ashoka. This fact led some authors to think that the most sophisticated capitals were actually the earliest in the sequence of Ashokan pillars and that style degraded over a short period of time.[2]

These were made probably made at the beginning of the reign of Ashoka (reigned 262-233 BCE), from the year 12 of his reign, that is, from 250 BCE.[3]

History

Ashoka was the third monarch of the Maurya Empire in India, reigning from around 269 BCE.[4] Ashoka famously converted to Buddhism and renounced violence soon after being victorious in a gruesome Kalinga War, yet filled with deep remorse for the bloodshed of the war. Although he was a major historical figure, little definitive information was known as there were few records of his reign until the 19th century when a large number of his edicts, inscribed on rocks and pillars, were found in India, Nepal, Pakistan and Afghanistan. These many edicts were concerned with practical instructions in running a kingdom such as the design of irrigation systems and descriptions of Ashoka's beliefs in peaceful moral behavior. They contain little personal detail about his life.[4]

List of the Minor Pillar Edicts

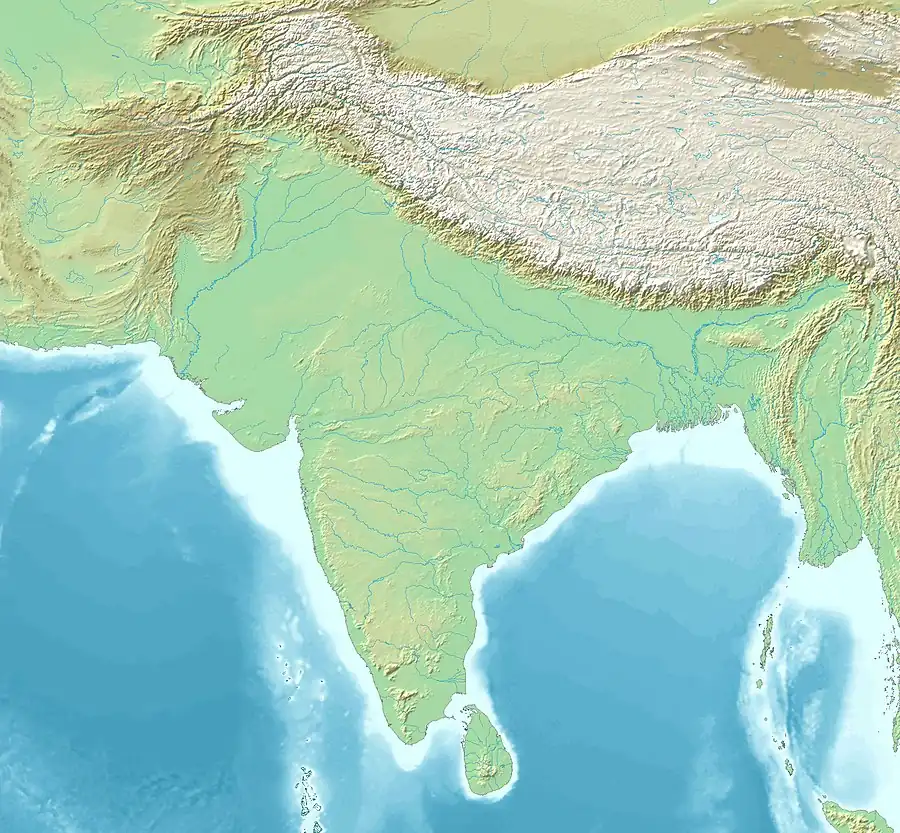

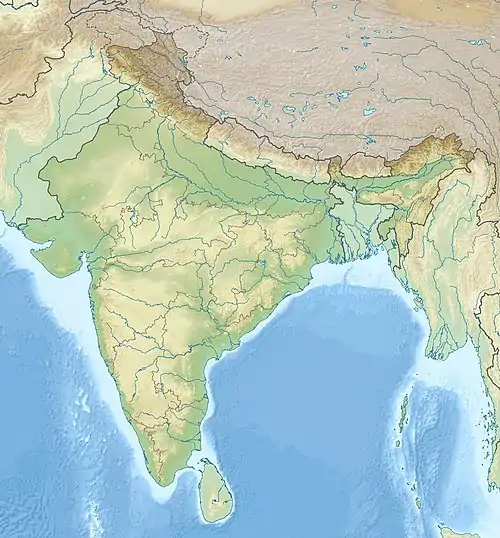

Asoka’s Minor Pillar Edicts are exclusively inscribed on several of the Pillars of Ashoka, at Sarnath, Sanchi, Allahabad (a pillar initially located in Kosambi), Rummindei and Nigali Sagar. They are all in the Prakrit language and the Brahmi script.

These pillar edicts are:[1]

- The Schism Edicts

Asoka’s injunction against shism in the Samgha. Found on the Sarnath, Sanchi and Allahabad pillars. These are among the earliest inscriptions of Ashoka, at a time when inscription techniques in India where not yet mature.[5] In contrast, the lion capitals crowning these edicts (Sarnath and Sanchi) are the most refined of those produced during the time of Ashoka.[5]

All the Schism edits are rather fragmentary, but the similarity of their messages permit a clear reconstruction:

"The Beloved of the Gods orders the officers of Kauśāmbī/ Pāṭa(liputra) thus: No one is to cause dissention in the Order. The Order of monks and nuns has been united, and this unity should last for as long as my sons and great grandsons, and the moon and the sun. Whoever creates a schism in the Order, whether monk or nun, is to be dressed in white garments, and to be put in a place not inhabited by monks or nuns. For it is my wish that the Order should remain united and endure for long. This is to be made known to the Order of monks and the Order of nuns."[6]

Kosambi-Allahabad Schism Edict.

Kosambi-Allahabad Schism Edict. Sanchi Schism Edict.

Sanchi Schism Edict. Sarnath Schism Edit.

Sarnath Schism Edit.

- The Queen's Edict

Ashoka announces that the Queen should be credited for her gifts. Found on the Allahabad pillar.

"On the order of the Beloved of the Gods, the officers everywhere are to be instructed that whatever may be the gift of the second queen, whether a mango-grove, a monastery, an institution for dispensing charity or any other donation, it is to be counted to the credit of that queen … the second queen, the mother of Tīvala, Kāruvākī."[6]

Commemorative inscriptions

Although generally catalogued among the "Minor Pillar Edicts", the two inscriptions found in Lumbini and at Nigali Sagar are in the past tense and in the ordinary third person (not the royal third person), suggesting that are not pronouncements of Ashoka himself, but rather later commemorations of his visits in the area.[7] Being commemorative, these two inscriptions may have been written significantly later than the other Ashokan inscriptions.[7]

- The Lumbini pillar inscription

Records the visit of Ashoka to Lumbini, location of the birth of the Buddha, in today's Nepal.

| Translation (English) | Transliteration (original Brahmi script) | Inscription (Prakrit in the Brahmi script) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

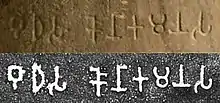

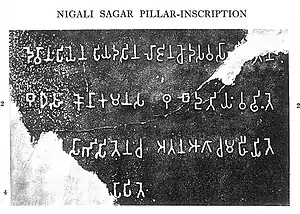

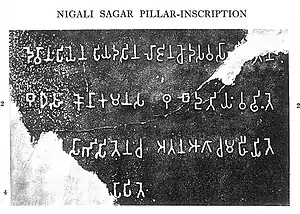

- The Nigali Sagar pillar inscription

At Nigali Sagar, Ashoka mentions his dedication for the enlargement of the Stupa dedicated to the Kanakamuni Buddha.

| Translation (English) | Transliteration (original Brahmi script) | Inscription (Prakrit in the Brahmi script) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Rubbing of the inscription. |

Inscription techniques

The inscription technique of the early Edicts, particularly the Schism Edcits at Sarnath, Sanchi and Kosambi-Allahabad, is very poor compared for example to the later Major Pillar Edicts, however the Minor Pillar Edicts are often associated with some of the artistically most sophisticated pillar capitals of Ashoka, such as the renowned Lion Capital of Ashoka which crowned the Sarnath Minor Pillar Edict, or the very similar, but less well preserved Sanchi lion capital which crowned the very clumsily inscribed Schism Edict of Sanchi.[15] These edicts were probably made at the beginning of the reign of Ashoka (reigned 262-233 BCE), from the year 12 of his reign, that is, from 256 BCE.[3]

According to Irwin, the Brahmi inscriptions on the Sarnath and Sanchi pillars were made by inexperienced Indian engravers at a time when stone engraving was still new in India, whereas the very refined Sarnath capital itself was made under the tutelage of craftsmen from the former Achaemenid Empire, trained in Perso-Hellenistic statuary and employed by Ashoka.[14] This suggests that the most sophisticated capitals were actually the earliest in the sequence of Ashokan pillars and that style degraded over a short period of time.[15]

The Rummindei and Nigali Sagar edicts, inscribed on pillars erected by Ashoka later in his reign (19th and 20th year) display a high level of inscriptional technique with a good regularity in the lettering.[14]

Description of the Minor Pillar Edicts

The Minor Rock Edicts of Ashoka are exclusively inscribed on some of the Pillars of Ashoka, at Sanchi, Sarnath, Allahabad, Rummindei and Nigali Sagar.

| Name | Location | Map | Pillar & inscription | Capital/ Close-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarnath (Lion Capital of Ashoka) | Located in Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh Schism Edict.[16] Sarnath Schism Edict of Ashoka:

|

|  | |

| Sanchi | Located in Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh Schism Edict.[16] Sanchi Schism Edict of Ashoka:

|

| .jpg.webp) | |

| Allahabad (Kosambi) | Located in Allahabad (originally in Kosambi, Bihar Schism Edict, Queen's Edict. Several Major Pillar Edicts (1-6) are also inscribed.[16] Allahabad Schism Edict of Ashoka:

Allahabad Queen's Edict:

|

| ||

| Rummindei /Paderia | Located in Lumbini, Nepal Rummindei Edict.[16] Rummindei Edict of Ashoka:

|

| .jpg.webp) | |

| Nigali Sagar | Located in Nigali Sagar, Nepal Nigali Sagar Edict.[16] Nigali Sagar Edict of Ashoka:

|

|  |

See also

References

- Romila Thapar (1997). "Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas" (PDF). Columbia University. Delhi: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- The True Chronology of Aśokan Pillars, John Irwin, Artibus Asiae, Vol. 44, No. 4 (1983), pp. 247-265

- Yailenko, Valeri P. (1990). "Les maximes delphiques d'Aï Khanoum et la formation de la doctrine du dhamma d'Asoka". Dialogues d'Histoire Ancienne (in French). 16: 239–256. doi:10.3406/dha.1990.1467.

- "The Edicts of King Ashoka". Ven. S. Dhammika. Archived from the original on 14 March 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2007.

- Irwin, John (1983). "The True Chronology of Aśokan Pillars". Artibus Asiae. 44 (4): 247–265. doi:10.2307/3249612. JSTOR 3249612.

- Thapar, Romila (2012). "Appendix V: A Translation of the Edicts of Aśoka" (PDF). Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas (3rd ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 388–390. ISBN 9780198077244. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2017). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-691-17632-1.

- Hultzsch, E. (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 164-165

- Hultzsch, E. (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). p. 164.

- British Library Online

- "Dr. Fuhrer went from Nigliva to Rummindei where another Priyadasin lat has been discovered... and an inscription about 3 feet below surface, had been opened by the Nepalese" in Calcutta, Maha Bodhi Society (1921). The Maha-Bodhi. p. 226.

- Basanta Bidari - 2004 Kapilavastu: the world of Siddhartha - Page 87

- Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 165.

- Irwin, John (1983). "The True Chronology of Aśokan Pillars". Artibus Asiae. 44 (4): 250&264. doi:10.2307/3249612. JSTOR 3249612.

- The True Chronology of Aśokan Pillars, John Irwin, Artibus Asiae, Vol. 44, No. 4 (1983), pp. 264

- The Geopolitical Orbits of Ancient India: The Geographical Frames of the ... by Dilip K Chakrabarty p.32

- John Marshall, "A Guide to Sanchi" p.93 Public Domain text

- Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 160.

- Hultzsch, E. /1925). Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 164-165

- Amaravati: The Art of an early Buddhist Monument in context. p.23