Minuscule 700

Minuscule 700 (in the Gregory-Aland numbering of New Testament manuscripts), ε 133 (in the von Soden numbering of New Testament manuscripts),[1]: 72 is a Greek New Testament minuscule manuscript of the Gospels, written on parchment. It was formerly labelled as 604 in all New Testament manuscript lists (such as that of textual critics Frederick H. A. Scrivener, and Hoskier), however textual critic Caspar René Gregory gave it the number 700.[2]: 213 Using the study of comparative writing styles (palaeography), it has been dated to the 11th century.[3] It is currently housed at the British Library (Egerton MS 2610) in London.[3]

| New Testament manuscript | |

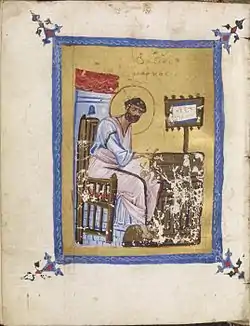

Folio 91 verso, Evangelist Mark | |

| Text | Gospels |

|---|---|

| Date | 11th century |

| Script | Greek |

| Now at | British Library, Egerton 2610 |

| Size | 14.8 cm by 11.7 cm |

| Type | Caesarean text-type |

| Category | III |

| Note | numerous unique readings |

Description

The manuscript is a codex (the forerunner to the modern book), containing the complete text of the Gospels on 297 parchment leaves (14.8 cm by 11.7 cm).[4]: i The text is written in one column per page, 19 lines per page in minuscule letters,[3] with around 30 letters on each line.[5][4]: i The initial letters are in gold and blue ink, as well as the simple headpieces (titles to each Gospel) and tailpieces (ending to each Gospel).[4]: ii Iota subscript (a small Greek letter ι (iota) written underneath vowels in certain words to indicate a change of sound) is never used by the initial copyist, however iota adscript (where the ι is written as part of the main text with the same function as the iota subscript) is employed quite often, most frequently with substantives, definite articles, and pronouns.[4]: vi The initial copyist however has used iota adscript erroneously very often: scholar and textual critic Herman C. Hoskier notes the copyist inserted iota adscript incorrectly 80 times in Matthew, 27 times in Mark, 19 times in Luke, and 23 times in John.[4]: vi–viii

The text of the Gospels is divided according to the chapters (known as κεφαλαια / kephalaia), whose numbers are placed in the margin of the text, with the titles of the chapters given at the top of the pages, with gold and red ink.[5][4]: ii The tables of content lists are placed before each Gospel (Matthew, Mark, Luke).[5][4]: ii The chapters to Matthew contains only 17 entries, with the list being left unfinished.[4]: ii There is also a division into smaller sections, the Ammonian sections with references to the Eusebian Canons (an early system of dividing the four Gospels into different sections), although this is done in John very rarely.[2]: 213

It contains the Epistula ad Carpianum (a letter from the early church writer Eusebius of Caesarea, outlying his gospel harmony system, his chapter divisions of the four gospels, and their purpose); Eusebian Canon tables (list of chapters) at the beginning of the codex; subscriptions (end titles) at the close of each Gospel; illustrations of the evangelists; and lectionary markings (to indicate what verse was to be read on a specific day in the churches yearly calendar) in the margin, written in gold ink.[5][4]: ii The initial copyist left space between the weekly readings for insertion of the ἀρχ(η) (beginning) and τελ(ος) (end) markings, however they were left unfinished.[4]: ii The original copyist didn't add any to the Gospels of Matthew and Mark, but a few were inserted by a later copyist.[4]: ii The initial copyist did however insert a few in the Gospels of Luke (Luke 6:17; 10:16, 21, 22, 25, 37, 38; 12:16, 32) and John (John 1:17/18, 52/2:1), in gold ink.[4]: ii

Quotations from the Old Testament are sometimes marked in the margin by a diplai (>), written in gold ink.[4]: vi These are found at Matthew 1:23; 2:6, 15, 18; 4:6, 7, 15, 16; Luke 3:4-6; 4:10, 11, 18; 10:27; John 19:24, 37. There are none in Mark.[4]: vi Accents (used to indicate voiced pitch changes) and breathing marks (utilised to designate vowel emphasis) are utilised throughout.[4]: xiv Three forms of the round stops (above, middle, and below the line), the comma, (applied to show the end of phrases/sentences) and the semicolon (used to mark a question has been asked) are employed.[4]: xiv The three stops and comma are partially applied, although incorrectly in many instances.[4]: xiv The semicolon is only used sparingly, and mostly neglected where the end of a question is.[4]: xiv Itacism (spelling errors due to similar sounding letters) mistakes are witnessed, however not as many as in other codices, with Hoskier noting a total of 205 (33 in Matthew; 32 in Mark; 102 in Luke; and 38 in John).[4]: xiv–xv Some cases of homoeoteleuton are noticed, but very rarely (this being the omission of words/phrases which finish with either similar letters, or the same word).[4]: xv

Most of the conventional nomina sacra (special names/words considered sacred in Christianity - usually the first and last letters of the name/word in question are written, followed by an overline; sometimes other letters from within the word are used as well) are employed throughout (the following list is for nominative case (subject) forms): ις (ιησους / Jesus); χς (χριστος / Christ); θς (θεος / God); κς (κυριος / Lord); πνα (πνευμα / Spirit); δαδ (δαυιδ / David); ιηλ (ισραηλ / Israel); πηρ (πατηρ / father); μηρ (μητηρ / mother); σηρ (σωτηρ / saviour); σρια (σωτηρια / salvation); σριος (σωτηριος / salvation); ουνος (ουρανος / heaven); ουνοις (ουρανιος / heavenly); ανος (ανθρωπος / man); (σταυρος / cross).[4]: xiii The nomen sacrum (singular of nomina sacra) for υιος (son / υς) is seen in Matthew 1:23, 3:17, 17:15; Mark 10:47; Luke 1:13, 31, 3:2.[4]: xiii The nomen sacrum for Ιερουσαλημ (Jerusalem / ιλημ) is seen in Matthew 23:37; Luke 2:25, 38, 41, 43, 5:17, 6:17, 9:31, 53, 10:30, 13:4, 22, 23, 34, 19:11, 23:28, 24:13, 18, 33, 47, 49, 52.[4]: xiii

Text

The Greek text of the codex has been considered as a representative of the Caesarean text-type. The text-types are groups of different New Testament manuscripts which share specific or generally related readings, which then differ from each other group, and thus the conflicting readings can separate out the groups. These are then used to determine the original text as published; there are three main groups with names: Alexandrian, Western, and Byzantine.[6]: 205–230 The Caesarean text-type however (initially identified by biblical scholar Burnett Hillman Streeter) has been contested by several text-critics, such as Kurt and Barbara Aland.[7]: 55–56 Aland placed it in Category III of his New Testament manuscript text classification system.[7] Category III manuscripts are described as having "a small but not a negligible proportion of early readings, with a considerable encroachment of [Byzantine] readings, and significant readings from other sources as yet unidentified."[7]: 335 Among Aland's test collation passages (a specific list of verses in the New Testament which have been determined to show to which text-type a manuscript belongs), the codex has 153 variants in agreement with the Byzantine text, 81 with the Byzantine and Nestle-Aland texts, 35 with the Nestle-Aland text, and 58 distinctive readings.[7]

According to the Claremont Profile Method (a specific analysis method of textual data), it has a mixed textual relationship in Luke 1, accords to the Alexandrian text-type in Luke 10, and represents the textual family Kx in Luke 20. It belongs to the textual family subgroup 35.[8]

In Matthew 27:16 it has the famous textual variant "Ιησουν τον Βαραββαν" (Jesus Barabbas). This variant is found in Codex Koridethi (Θ), and manuscripts of textual group Family 1 (ƒ1). It lacks Mark 11:26.[9]: 128

Together with minuscule 162, it contains the remarkable reading in the Gospel of Luke 11:2: ἐλθέτω τὸ πνεῦμά σου τὸ ἅγιον ἐφ' ἡμᾶς καὶ καθαρισάτω ἡμᾶς (May your Holy Spirit come upon us and cleanse us), instead of ελθετω η βασιλεια σου (May your kingdom come) in the Lord's Prayer.[6] This peculiar reading does not appear in any other manuscript, but it was derived from a very old archetype, because it is present in Marcion's text of the third Gospel (Marcion was an early gnostic, considered a heretic by contemporary and later Christians), and is also attested by the church father Gregory of Nyssa in his quotations of the Gospel of Luke in his writings.[10]

Hoskier's collation (a comparison of a manuscript's text with that of another, and differences between them recorded) notes 2724 variations from the Textus Receptus (before the 1900s, this was the most common printed Greek New Testament): of these 791 are omissions; 353 are additions; and 270 textual variants have not been found in any other manuscript.[10][4]: xxviii

- Notable readings

Below are some readings of the manuscript which agree or disagree with variant readings in other Greek manuscripts, or with varying ancient translations of the New Testament. See the main article Textual variants in the New Testament.

- απεκριθη λεγων (he answered, saying) — 700 E 565

- απεκριτη (he answered) — D it

- λεγει αυτω (he said to him) — Majority of manuscripts

- -

- λεγιων ονομα μοι (my name is Legion) — 700* אc2 Bc2 C L Δ 579

- λεγεων (Legeon) — 700c(vid) א* B* A W Θ ƒ1 ƒ13 Byz[9]: 102

- μη αποστερησης (do not defraud)

- οὐκ ἔξεστιν (not lawful) — 700 𝔓4 B (D) N lat sa bo arm geo

- οὐκ ἔξεστιν ποιεῖν (not lawful to do) - Majority of manuscripts[9]: 170

- αλλα ρυσαι ημας απο του πονηρου (but deliver us from evil)

History

The author of the codex is unknown. It was probably written in Constantinople (modern day Istanbul in Turkey).[12]

The codex was bought on the 28th April, 1882 for the British Museum,[4][2]: 214 through the auspices of Edward Maunde Thompson, the then Principal Keeper of manuscripts at the British Museum.[4] The codex was previously in the hands of a German bookseller.[4]

It was examined by Anglican clergyman Dean Burgon, and it was described and collated by scholar W. H. Simcox,[13] Scrivener, and Hoskier. The collation and comments of W. H. Simcox were severely criticised by Hoskier for its numerous mistakes.[4]: xv–xxii The manuscript is now located in the British Library in London (Egerton MS 2610).[3]

References

- Gregory, Caspar René (1908). Die griechischen Handschriften des Neuen Testament. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

- Gregory, Caspar René (1900). Textkritik des Neuen Testaments. Vol. 1. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

- Aland, Kurt; M. Welte; B. Köster; K. Junack (1994). Kurzgefasste Liste der griechischen Handschriften des Neues Testaments. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter. p. 88. ISBN 3-11-011986-2.

- Hoskier, Herman C. (1890). A Full Account and Collation of the Greek Cursive Codex Evangelium 604. London: David Nutt Publishers.

- Scrivener, Frederick Henry Ambrose; Edward Miller (1894). A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament. Vol. 1 (4 ed.). London: George Bell & Sons. p. 261.

- Metzger, Bruce Manning; Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption and Restoration (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 90. ISBN 0-19-516667-1.

- Aland, Kurt; Aland, Barbara (1995). The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. Erroll F. Rhodes (trans.). Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1.

- Wisse, Frederik (1982). The Profile Method for the Classification and Evaluation of Manuscript Evidence, as Applied to the Continuous Greek Text of the Gospel of Luke. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 64. ISBN 0-8028-1918-4.

- Aland, Kurt; Black, Matthew; Martini, Carlo M.; Metzger, Bruce M.; Wikgren, Allen, eds. (1981). Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece (26 ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelstiftung. ISBN 3-438-051001. (NA26)

- Koester, Helmut (1995). Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Walter de Gruyter. p. 31. doi:10.1515/9783110812657.39.

- Aland, Kurt; Black, Matthew; Martini, Carlo M.; Metzger, Bruce M.; Wikgren, Allen, eds. (1983). The Greek New Testament (3rd ed.). Stuttgart: United Bible Societies. (UBS3)

- Minuscule 700 at the British Library

- Simcox, W. H. (1884). "Collation of the British Museum MS Evan. 604" (PDF). American Journal of Philology. 5 (4): 454–465.

Further reading

- Scrivener, Frederick Henry Ambrose (1893). Adversaria Critica Sacra. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Streeter, Burnett Hillman (1924). The Four Gospels: A Study of Origins. London: MacMillan..

- Metzger, Bruce Manning (1981). Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Palaeography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 122.

External links

- Minuscule 700 at the British Library.

- Minuscule 700 at the Encyclopedia of Textual Criticism.

- 700 (GA) at the CSNTM.