Mobile web

The mobile web comprises mobile browser-based World Wide Web services accessed from handheld mobile devices, such as smartphones or feature phones, through a mobile or other wireless network.

History and development

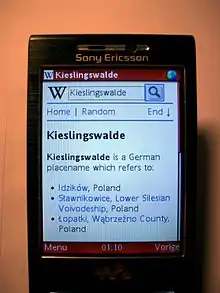

Traditionally, the World Wide Web has been accessed via fixed-line services on laptops and desktop computers. However, the web is now more accessible by portable and wireless devices. Early 2010 ITU (International Telecommunication Union) report said that with current growth rates, web access by people on the go – via laptops and smart mobile devices – was likely to exceed web access from desktop computers within the following five years.[1] In January 2014, mobile internet use exceeded desktop use in the United States.[2] The shift to mobile Web access has accelerated since 2007 with the rise of larger multitouch smartphones, and since 2010 with the rise of multitouch tablet computers. Both platforms provide better Internet access, screens, and mobile browsers, or application-based user Web experiences than previous generations of mobile devices. Web designers may work separately on such pages, or pages may be automatically converted, as in Mobile Wikipedia. Faster speeds, smaller, feature-rich devices, and a multitude of applications continue to drive explosive growth for mobile internet traffic. The 2017 Virtual Network Index (VNI) report produced by Cisco Systems forecasts that by 2021, there will be 5.5 billion global mobile users (up from 4.9 billion in 2016).[3] Additionally, the same 2017 VNI report forecasts that average access speeds will increase by roughly three times from 6.8 Mbit/s to 20 Mbit/s in that same period with video comprising the bulk of the traffic (78%).

The distinction between mobile web applications and native applications is anticipated to become increasingly blurred, as mobile browsers gain direct access to the hardware of mobile devices (including accelerometers and GPS chips), and the speed and abilities of browser-based applications improve. Persistent storage and access to sophisticated user interface graphics functions may further reduce the need for the development of platform-specific native applications.

The mobile web has also been called Web 3.0, drawing parallels to the changes users were experiencing as Web 2.0 websites proliferated.[4][5][6]

The mobile web was first popularized by the silicon valley company, Unwired Planet.[7] In 1997, Unwired Planet, Nokia, Ericsson, and Motorola started the WAP Forum to create and harmonize the standards to ease the transition to bandwidth networks and small display devices. The WAP standard was built on a three-layer, middleware architecture that fueled the early growth of the mobile web but was made virtually irrelevant with faster networks, larger displays, and advanced smartphones based on Apple's iOS and Google's Android software.

Mobile points of access

Mobile Internet refers to Internet access and mainly usage of Internet using a cellular telephone service provider or mobile wireless network. It is wireless Internet access and usage that can easily change to next wireless Internet (radio) tower while mobile user with his/her device is moving across the service area. It can also refer to a desktop computer or other not in move device that stays connected to one tower as using mobile internet, but this is not the prime meaning of "mobile" here. Wi-Fi and other better Internet connectivity methods are commonly available for users not on the move. Cellular base stations are more expensive to provide compared to a wireless base station that connects directly to the network of an internet service provider, rather than through the telephone system.

A mobile phone, such as a smartphone, that connects to Internet hypertext data or voice services without going through the cellular base station is not on the service mobile Internet but connected to wireless mobile Internet. A laptop with a broadband modem and a cellular service provider subscription, that is traveling on a bus through the city is on mobile Internet.

A mobile broadband modem "tethers" the smartphone to one or more computers or other end-user devices to provide access and usage to the Internet via the protocols that cellular telephone service providers may offer.

According to BuzzCity, the mobile internet increased by 30% from Q1 to Q2 2011. The four countries which have advertising impression (?) in total more than 1 billion in one quarter were India, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the United States.[8] As of July 2012, approximately 10.5% of all web traffic occurs through mobile devices (up from 4% in December 2010).[9]

Mobile web access today still suffers from interoperability and usability problems. Interoperability issues stem from the platform fragmentation of mobile devices, mobile operating systems, and browsers. Usability problems are centered on the small physical size of the mobile phone form factors (limits on display resolution and user input/operating). Despite these shortcomings, many mobile developers choose to create apps using mobile web. A June 2011 research on mobile development found mobile web the third most used platform, trailing Android and iOS.[10]

Mobile standards

The Mobile Web Initiative (MWI) was set up by the W3C to develop the best practices and technologies relevant to the mobile web. The goal of the initiative is to make browsing the web from mobile devices more reliable and accessible. The main aim is to evolve standards of data formats from Internet providers that are tailored to the specifications of particular mobile devices. The W3C has published guidelines for mobile content, and is addressing the problem of device diversity by establishing a technology to support a repository of device descriptions.

W3C is also developing a validating scheme to assess the readiness of content for the mobile web, through its mobileOK Scheme, which will help content developers to determine if their content is web-ready quickly.[11] The W3C guidelines and mobileOK approach have not been immune from criticism. This emphasizes adaptation, which is now seen as the key process in achieving the ubiquitous web when combined with a device description repository.

mTLD, the registry for .mobi, has released a free testing tool called the MobiReady Report (see mobiForge) to analyze the mobile readiness of website.

Other standards for the mobile web are being documented and explored for particular applications by interested industry groups, such as the use of the mobile web for education and training.

Development

The first access to the mobile web was commercially offered in Finland at the end of 1996 on the Nokia 9000 Communicator phone via the Sonera and Radiolinja networks. This was access to the real internet. The first commercial launch of a mobile-specific browser-based web service was in 1999 in Japan when i-mode was launched by NTT DoCoMo.

The mobile web primarily utilizes lightweight pages like this one written in Extensible Hypertext Markup Language (XHTML) or Wireless Markup Language (WML) to deliver content to mobile devices. Many new mobile browsers are moving beyond these limits by supporting a wider range of Web formats, including variants of HTML commonly found on the desktop web.

Growth

.png.webp)

At one time, half the world had mobile phones.[12] The articles in 2007-2008 were slightly misleading because the real story at the time was that the number of mobile phone subscriptions had reached half the population of the world. In reality, many people have more than one subscription. For example, in Hong Kong, Italy and Ukraine, the mobile phone penetration rate has passed 140% (source wireless intelligence 2009). By 2009 even the number of unique users of mobile phones had reached half the planet when the ITU reported that the subscriber number was to reach 4.6 billion users which means 3.8 billion activated mobile phones in use, and 3.4 billion unique users of mobile phones. Mobile Internet data connections are following the growth of mobile phone connections albeit at a lower rate. In 2009 Yankee Group reported that 29% of all mobile phone users globally were accessing browser-based internet content on their phones. According to the BBC, there are now (2010) over 5 billion mobile phone users in the world.[13] According to Statista there were 1.57 billion smartphone owners in 2014, 2.32 billion in 2017 (now) and 2.87 billion are predicted in 2020.[14]

Many users in Europe and the United States are already users of the fixed internet when they first try the same experience on a mobile phone. Meanwhile, in other parts of the world, such as India, their first usage of the internet is on a mobile phone. Growth is fastest in parts of the world where the personal computer (PC) is not the first user experience of the internet. India, South Africa, Indonesia, and Saudi Arabia are seeing the fastest growth in mobile internet usage. To a great extent, this is due to the rapid adoption of mobile phones themselves. For example, the Morgan Stanley report states that the highest mobile phone adoption growth in 2006 was in Pakistan and India.

The widespread deployment of Web-enabled mobile devices (such as phones) make them a target of choice for content creators. Understanding their strengths and their limitations, and using technologies that fit these conditions are key to create success mobile-friendly Web content.[15]

Mobile internet has also been adopted in West Africa[16]

China has 155 million mobile internet users as of June 2009.[17]

Top-level domain

The .mobi sponsored top-level domain was launched specifically for the mobile Internet by a consortium of companies including Google, Microsoft, Nokia, Samsung, and Vodafone. By forcing sites to comply with mobile web standards, .mobi tries to ensure visitors a consistent and optimized experience on their mobile device. However, this domain has been criticized by several big names, including Tim Berners-Lee of the W3C, who claims that it breaks the device independence of the web:

It is fundamentally useful to be able to quote the URI for some information and then look up that URI in an entirely different context. For example, I may want to look up a restaurant on my laptop, bookmark it, and then, when I only have my phone, check the bookmark to have a look at the evening menu. Or, my travel agent may send me a pointer to my itinerary for a business trip. I may view the itinerary from my office on a large screen and want to see the map, or I may view it at the airport from my phone when all I want is the gate number.

Dividing the Web into information destined for different devices, or different classes of user, or different classes of information, fundamentally breaks the Web.

I urge ICANN not to create the ".mobi" top-level domain.

Advertising

Advertisers are increasingly using the mobile web as a platform to reach consumers. The total value of advertising on mobile was 2.2 billion dollars in 2007. A recent study by the Online Publishers Association, now called Digital Content Next (DCN), reported that about one-in-ten mobile web users said they have made a purchase based on a mobile web ad, while 23% said they had visited a Web site, 13% said they have requested more information about a product or service and 11% said they have gone to a store to check out a product.

Accelerated Mobile Pages

In the fall of 2015, Google announced it would be rolling out an open source initiative called "Accelerated Mobile Pages" or AMP. The goal of this project is to improve the speed and performance of content-rich pages which include video, animations, and graphics. Since the majority of the population now consumes the web through tablets and smartphones, having web pages that are optimized for these products is the primary need to AMP.[18][19]

The three main types of AMP are AMP HTML, AMP JS, and Google AMP Cache.[20]

Parity between accelerated mobile pages and canonical pages

A recent requirement – beginning 1 February 2018 – from Google requires the canonical page content should match the content on accelerated mobile pages. In creating a great user experience – and to avoid user interface traps – it's important to display the same content on Accelerated Mobile Pages as there are with the standard canonical pages.

Limitations

Though Internet access "on the go" provides advantages to many, such as the ability to communicate by email with others and obtain information anywhere, the web, accessed from mobile devices, has many limits, which may vary, depending on the device. However, newer smartphones overcome some of these restrictions. Some problems which may be encountered include:

- Small screen size – this makes it difficult or impossible to see text and graphics dependent on the standard size of a desktop computer screen. To display more information, smartphone screen sizes have been getting bigger.

- Lack of windows – on a desktop computer, the ability to open more than one window at a time allows for multi-tasking and easy revert to a previous page. Historically on mobile web, only one page could be displayed at a time, and pages could only be viewed in the sequence they were originally accessed. However, Opera Mini[21] was among the first allowing multiple windows, and browser tabs have become commonplace but few mobile browsers allow overlapping windows on the screen.

- Navigation – Navigation is a problem for websites not optimized for mobile devices as the content area is large, the screen size is small, and there is no scroll wheel or hover box feature.

- Lack of JavaScript and cookies – most devices do not support client-side scripting and storage of cookies (smartphones excluded), which are now widely used in most web sites to enhance the user experience, facilitating the validation of data entered by the page visitor, etc. This also results in web analytics tools being unable to uniquely identify visitors using mobile devices.

- Types of pages accessible – many sites that can be accessed on a desktop cannot on a mobile device. Many devices cannot access pages with a secured connection, Flash, or other similar software, PDFs, or video sites, although as of 2011, this has been changing.

- Speed – on most mobile devices, the speed of service is slow, sometimes slower than dial-up Internet access.

- Broken pages – on many devices, a single page as viewed on a desktop is broken into segments, each treated as a separate page. This further slows navigation.

- Compressed pages – many pages, in their conversion to mobile format, are squeezed into an order different from how they would customarily be viewed on a desktop computer.

- Size of messages – many devices have limits on the number of characters that can be sent in an email message.

- Cost – the access and bandwidth charges levied by cellphone networks can be high if there is no flat fee per month.

- Location of mobile user:

- If advertisements reach phone users in private locations, users find them more distressful (Banerjee & Dholakia, 2008)

- If the user is abroad the flat fee per month usually does not apply

- The situation in which ad reaches user – when advertisements reach users in work-related situations, they may be considered more intrusive than in leisure situations (Banerjee & Dholakia, 2008)

The inability of mobile web applications to access the local capabilities on the mobile device can limit their ability to provide the same features as native applications. The OMTP BONDI activity is acting as a catalyst to enable a set of JavaScript APIs which can securely access local capabilities on the mobile device. Specifications and a reference implementation[22] have been produced. Security is a key aspect of this provision to protect users from malicious web applications and widgets.

In addition to the limits of the device, some limits should be made known to users concerning the interference these devices cause in other electromagnetic technology.

The convergence of the Internet and phone, in particular, has caused hospitals to increase their mobile phone exclusion zones. A study by Erik van Lieshout and colleagues (Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam) have found that the General Packet Radio Service (GPRS) used in modern phones can affect machines from up to 3 meters away. The Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS) signals, used in 3G networks, have a smaller exclusion zone of just a few centimeters. The worst offenders in hospitals are doctors.

See also

References

- "Press Release: ITU sees 5 billion mobile subscriptions globally in 2010".

- McCullough, John (22 September 2014) WorldCat Discovery Services: OCLC presentation at ALA Annual 2014. OCLCVideo. YouTube. Retrieved 4 August 2015. start 4 minutes in YouTube

- "Mobile Visual Networking Index (VNI) Infographic". Cisco.

- "Web 3.0: The Mobile Era". TechCrunch. 11 August 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- "Web 3.0 to Merge the Physical and the Virtual – Technorati Business". Technorati.com. 26 September 2012. Archived from the original on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- Kevin Tea (28 August 2012). "Web 3.0 Is Here And It's Mobile | BCW". Businesscomputingworld.co.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- Glave, James (3 November 1997). "Handheld Internet Will Be Huge - Really!". Wired – via www.wired.com.

- "BuzzCity: Mobile Ads are Growing, Indonesia is Still #2 in The World". 18 July 2011.

- Macmanus, Richard. "Top Trends of 2012: The Continuing Rapid Growth of Mobile". ReadWriteWeb. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- "Developer Economics 2011". Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- "W3C mobileOK Basic Tests 1.0". www.w3.org. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Over 5 billion mobiles worldwide". BBC News. 9 July 2010.

- "Smartphone users worldwide 2020". Statista.

- "Mobile Web - W3C".

- Granguillhome Ochoa, Rogelio; Lach, Samantha; Masaki, Takaaki; Rodríguez-Castelán, Carlos (1 February 2022). "Mobile internet adoption in West Africa". Technology in Society. 68: 101845. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101845. ISSN 0160-791X.

- "chinanewswrap.com". ww5.chinanewswrap.com.

- "Introducing the Accelerated Mobile Pages Project, for a faster, open mobile web". Official Google Blog. 7 October 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- Bhawani, Chetan (7 October 2015). "Google introduces AMP Project to help speed up mobile web". Gizmo Times. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- "Accelerated Mobile Pages Project". www.ampproject.org. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- "Download Opera browser for mobile devices – Opera Software". Opera.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- "BONDI Reference Implementation". omtp.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

External links

- Jo Rabin, mTLD Mobile Top Level Domain (dotMobi), Mobile Web Best Practices, 2 November 2006

- Hoschka, Philipp, The W3C Mobile Web Initiative (MWI), W3C, 2005.

- W3C mobileOK Checker