Molecular orbital

In chemistry, a molecular orbital (/ɒrbədl/) is a mathematical function describing the location and wave-like behavior of an electron in a molecule. This function can be used to calculate chemical and physical properties such as the probability of finding an electron in any specific region. The terms atomic orbital and molecular orbital[lower-alpha 1] were introduced by Robert S. Mulliken in 1932 to mean one-electron orbital wave functions.[2] At an elementary level, they are used to describe the region of space in which a function has a significant amplitude.

In an isolated atom, the orbital electrons' location is determined by functions called atomic orbitals. When multiple atoms combine chemically into a molecule by forming a valence chemical bond, the electrons' locations are determined by the molecule as a whole, so the atomic orbitals combine to form molecular orbitals. The electrons from the constituent atoms occupy the molecular orbitals. Mathematically, molecular orbitals are an approximate solution to the Schrödinger equation for the electrons in the field of the molecule's atomic nuclei. They are usually constructed by combining atomic orbitals or hybrid orbitals from each atom of the molecule, or other molecular orbitals from groups of atoms. They can be quantitatively calculated using the Hartree–Fock or self-consistent field (SCF) methods.

Molecular orbitals are of three types: bonding orbitals which have an energy lower than the energy of the atomic orbitals which formed them, and thus promote the chemical bonds which hold the molecule together; antibonding orbitals which have an energy higher than the energy of their constituent atomic orbitals, and so oppose the bonding of the molecule, and non-bonding orbitals which have the same energy as their constituent atomic orbitals and thus have no effect on the bonding of the molecule.

Overview

A molecular orbital (MO) can be used to represent the regions in a molecule where an electron occupying that orbital is likely to be found. Molecular orbitals are approximate solutions to the Schrödinger equation for the electrons in the electric field of the molecule's atomic nuclei. However calculating the orbitals directly from this equation is far too intractable a problem. Instead they are obtained from the combination of atomic orbitals, which predict the location of an electron in an atom. A molecular orbital can specify the electron configuration of a molecule: the spatial distribution and energy of one (or one pair of) electron(s). Most commonly a MO is represented as a linear combination of atomic orbitals (the LCAO-MO method), especially in qualitative or very approximate usage. They are invaluable in providing a simple model of bonding in molecules, understood through molecular orbital theory. Most present-day methods in computational chemistry begin by calculating the MOs of the system. A molecular orbital describes the behavior of one electron in the electric field generated by the nuclei and some average distribution of the other electrons. In the case of two electrons occupying the same orbital, the Pauli principle demands that they have opposite spin. Necessarily this is an approximation, and highly accurate descriptions of the molecular electronic wave function do not have orbitals (see configuration interaction).

Molecular orbitals are, in general, delocalized throughout the entire molecule. Moreover, if the molecule has symmetry elements, its nondegenerate molecular orbitals are either symmetric or antisymmetric with respect to any of these symmetries. In other words, the application of a symmetry operation S (e.g., a reflection, rotation, or inversion) to molecular orbital ψ results in the molecular orbital being unchanged or reversing its mathematical sign: Sψ = ±ψ. In planar molecules, for example, molecular orbitals are either symmetric (sigma) or antisymmetric (pi) with respect to reflection in the molecular plane. If molecules with degenerate orbital energies are also considered, a more general statement that molecular orbitals form bases for the irreducible representations of the molecule's symmetry group holds.[4] The symmetry properties of molecular orbitals means that delocalization is an inherent feature of molecular orbital theory and makes it fundamentally different from (and complementary to) valence bond theory, in which bonds are viewed as localized electron pairs, with allowance for resonance to account for delocalization.

In contrast to these symmetry-adapted canonical molecular orbitals, localized molecular orbitals can be formed by applying certain mathematical transformations to the canonical orbitals. The advantage of this approach is that the orbitals will correspond more closely to the "bonds" of a molecule as depicted by a Lewis structure. As a disadvantage, the energy levels of these localized orbitals no longer have physical meaning. (The discussion in the rest of this article will focus on canonical molecular orbitals. For further discussions on localized molecular orbitals, see: natural bond orbital and sigma-pi and equivalent-orbital models.)

Formation of molecular orbitals

Molecular orbitals arise from allowed interactions between atomic orbitals, which are allowed if the symmetries (determined from group theory) of the atomic orbitals are compatible with each other. Efficiency of atomic orbital interactions is determined from the overlap (a measure of how well two orbitals constructively interact with one another) between two atomic orbitals, which is significant if the atomic orbitals are close in energy. Finally, the number of molecular orbitals formed must be equal to the number of atomic orbitals in the atoms being combined to form the molecule.

Qualitative discussion

For an imprecise, but qualitatively useful, discussion of the molecular structure, the molecular orbitals can be obtained from the "Linear combination of atomic orbitals molecular orbital method" ansatz. Here, the molecular orbitals are expressed as linear combinations of atomic orbitals.[5]

Linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO)

Molecular orbitals were first introduced by Friedrich Hund[6][7] and Robert S. Mulliken[8][9] in 1927 and 1928.[10][11] The linear combination of atomic orbitals or "LCAO" approximation for molecular orbitals was introduced in 1929 by Sir John Lennard-Jones.[12] His ground-breaking paper showed how to derive the electronic structure of the fluorine and oxygen molecules from quantum principles. This qualitative approach to molecular orbital theory is part of the start of modern quantum chemistry. Linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO) can be used to estimate the molecular orbitals that are formed upon bonding between the molecule's constituent atoms. Similar to an atomic orbital, a Schrödinger equation, which describes the behavior of an electron, can be constructed for a molecular orbital as well. Linear combinations of atomic orbitals, or the sums and differences of the atomic wavefunctions, provide approximate solutions to the Hartree–Fock equations which correspond to the independent-particle approximation of the molecular Schrödinger equation. For simple diatomic molecules, the wavefunctions obtained are represented mathematically by the equations

where and are the molecular wavefunctions for the bonding and antibonding molecular orbitals, respectively, and are the atomic wavefunctions from atoms a and b, respectively, and and are adjustable coefficients. These coefficients can be positive or negative, depending on the energies and symmetries of the individual atomic orbitals. As the two atoms become closer together, their atomic orbitals overlap to produce areas of high electron density, and, as a consequence, molecular orbitals are formed between the two atoms. The atoms are held together by the electrostatic attraction between the positively charged nuclei and the negatively charged electrons occupying bonding molecular orbitals.[13]

Bonding, antibonding, and nonbonding MOs

When atomic orbitals interact, the resulting molecular orbital can be of three types: bonding, antibonding, or nonbonding.

- Bonding interactions between atomic orbitals are constructive (in-phase) interactions.

- Bonding MOs are lower in energy than the atomic orbitals that combine to produce them.

- Antibonding interactions between atomic orbitals are destructive (out-of-phase) interactions, with a nodal plane where the wavefunction of the antibonding orbital is zero between the two interacting atoms

- Antibonding MOs are higher in energy than the atomic orbitals that combine to produce them.

- Nonbonding MOs are the result of no interaction between atomic orbitals because of lack of compatible symmetries.

- Nonbonding MOs will have the same energy as the atomic orbitals of one of the atoms in the molecule.

Sigma and pi labels for MOs

The type of interaction between atomic orbitals can be further categorized by the molecular-orbital symmetry labels σ (sigma), π (pi), δ (delta), φ (phi), γ (gamma) etc. These are the Greek letters corresponding to the atomic orbitals s, p, d, f and g respectively. The number of nodal planes containing the internuclear axis between the atoms concerned is zero for σ MOs, one for π, two for δ, three for φ and four for γ.

σ symmetry

A MO with σ symmetry results from the interaction of either two atomic s-orbitals or two atomic pz-orbitals. An MO will have σ-symmetry if the orbital is symmetric with respect to the axis joining the two nuclear centers, the internuclear axis. This means that rotation of the MO about the internuclear axis does not result in a phase change. A σ* orbital, sigma antibonding orbital, also maintains the same phase when rotated about the internuclear axis. The σ* orbital has a nodal plane that is between the nuclei and perpendicular to the internuclear axis.[14]

π symmetry

A MO with π symmetry results from the interaction of either two atomic px orbitals or py orbitals. An MO will have π symmetry if the orbital is asymmetric with respect to rotation about the internuclear axis. This means that rotation of the MO about the internuclear axis will result in a phase change. There is one nodal plane containing the internuclear axis, if real orbitals are considered.

A π* orbital, pi antibonding orbital, will also produce a phase change when rotated about the internuclear axis. The π* orbital also has a second nodal plane between the nuclei.[14][15][16][17]

δ symmetry

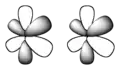

A MO with δ symmetry results from the interaction of two atomic dxy or dx2-y2 orbitals. Because these molecular orbitals involve low-energy d atomic orbitals, they are seen in transition-metal complexes. A δ bonding orbital has two nodal planes containing the internuclear axis, and a δ* antibonding orbital also has a third nodal plane between the nuclei.

φ symmetry

Theoretical chemists have conjectured that higher-order bonds, such as phi bonds corresponding to overlap of f atomic orbitals, are possible. There is no known example of a molecule purported to contain a phi bond.

Gerade and ungerade symmetry

For molecules that possess a center of inversion (centrosymmetric molecules) there are additional labels of symmetry that can be applied to molecular orbitals. Centrosymmetric molecules include:

- Homonuclear diatomics, X2

- Octahedral, EX6

- Square planar, EX4.

Non-centrosymmetric molecules include:

- Heteronuclear diatomics, XY

- Tetrahedral, EX4.

If inversion through the center of symmetry in a molecule results in the same phases for the molecular orbital, then the MO is said to have gerade (g) symmetry, from the German word for even. If inversion through the center of symmetry in a molecule results in a phase change for the molecular orbital, then the MO is said to have ungerade (u) symmetry, from the German word for odd. For a bonding MO with σ-symmetry, the orbital is σg (s' + s'' is symmetric), while an antibonding MO with σ-symmetry the orbital is σu, because inversion of s' – s'' is antisymmetric. For a bonding MO with π-symmetry the orbital is πu because inversion through the center of symmetry for would produce a sign change (the two p atomic orbitals are in phase with each other but the two lobes have opposite signs), while an antibonding MO with π-symmetry is πg because inversion through the center of symmetry for would not produce a sign change (the two p orbitals are antisymmetric by phase).[14]

MO diagrams

The qualitative approach of MO analysis uses a molecular orbital diagram to visualize bonding interactions in a molecule. In this type of diagram, the molecular orbitals are represented by horizontal lines; the higher a line the higher the energy of the orbital, and degenerate orbitals are placed on the same level with a space between them. Then, the electrons to be placed in the molecular orbitals are slotted in one by one, keeping in mind the Pauli exclusion principle and Hund's rule of maximum multiplicity (only 2 electrons, having opposite spins, per orbital; place as many unpaired electrons on one energy level as possible before starting to pair them). For more complicated molecules, the wave mechanics approach loses utility in a qualitative understanding of bonding (although is still necessary for a quantitative approach). Some properties:

- A basis set of orbitals includes those atomic orbitals that are available for molecular orbital interactions, which may be bonding or antibonding

- The number of molecular orbitals is equal to the number of atomic orbitals included in the linear expansion or the basis set

- If the molecule has some symmetry, the degenerate atomic orbitals (with the same atomic energy) are grouped in linear combinations (called symmetry-adapted atomic orbitals (SO)), which belong to the representation of the symmetry group, so the wave functions that describe the group are known as symmetry-adapted linear combinations (SALC).

- The number of molecular orbitals belonging to one group representation is equal to the number of symmetry-adapted atomic orbitals belonging to this representation

- Within a particular representation, the symmetry-adapted atomic orbitals mix more if their atomic energy levels are closer.

The general procedure for constructing a molecular orbital diagram for a reasonably simple molecule can be summarized as follows:

1. Assign a point group to the molecule.

2. Look up the shapes of the SALCs.

3. Arrange the SALCs of each molecular fragment in order of energy, noting first whether they stem from s, p, or d orbitals (and put them in the order s < p < d), and then their number of internuclear nodes.

4. Combine SALCs of the same symmetry type from the two fragments, and from N SALCs form N molecular orbitals.

5. Estimate the relative energies of the molecular orbitals from considerations of overlap and relative energies of the parent orbitals, and draw the levels on a molecular orbital energy level diagram (showing the origin of the orbitals).

6. Confirm, correct, and revise this qualitative order by carrying out a molecular orbital calculation by using commercial software.[18]

Orbital degeneracy

Molecular orbitals are said to be degenerate if they have the same energy. For example, in the homonuclear diatomic molecules of the first ten elements, the molecular orbitals derived from the px and the py atomic orbitals result in two degenerate bonding orbitals (of low energy) and two degenerate antibonding orbitals (of high energy).[13]

Ionic bonds

When the energy difference between the atomic orbitals of two atoms is quite large, one atom's orbitals contribute almost entirely to the bonding orbitals, and the other atom's orbitals contribute almost entirely to the antibonding orbitals. Thus, the situation is effectively that one or more electrons have been transferred from one atom to the other. This is called an (mostly) ionic bond.

Bond order

The bond order, or number of bonds, of a molecule can be determined by combining the number of electrons in bonding and antibonding molecular orbitals. A pair of electrons in a bonding orbital creates a bond, whereas a pair of electrons in an antibonding orbital negates a bond. For example, N2, with eight electrons in bonding orbitals and two electrons in antibonding orbitals, has a bond order of three, which constitutes a triple bond.

Bond strength is proportional to bond order—a greater amount of bonding produces a more stable bond—and bond length is inversely proportional to it—a stronger bond is shorter.

There are rare exceptions to the requirement of molecule having a positive bond order. Although Be2 has a bond order of 0 according to MO analysis, there is experimental evidence of a highly unstable Be2 molecule having a bond length of 245 pm and bond energy of 10 kJ/mol.[14][19]

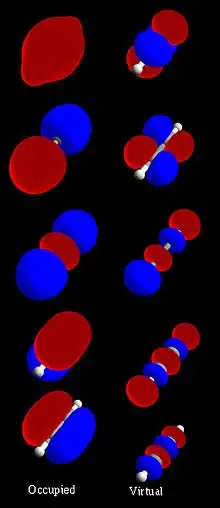

HOMO and LUMO

The highest occupied molecular orbital and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital are often referred to as the HOMO and LUMO, respectively. The difference of the energies of the HOMO and LUMO is called the HOMO-LUMO gap. This notion is often the matter of confusion in literature and should be considered with caution. Its value is usually located between the fundamental gap (difference between ionization potential and electron affinity) and the optical gap. In addition, HOMO-LUMO gap can be related to a bulk material band gap or transport gap, which is usually much smaller than fundamental gap.

Examples

Homonuclear diatomics

Homonuclear diatomic MOs contain equal contributions from each atomic orbital in the basis set. This is shown in the homonuclear diatomic MO diagrams for H2, He2, and Li2, all of which containing symmetric orbitals.[14]

H2

As a simple MO example, consider the electrons in a hydrogen molecule, H2 (see molecular orbital diagram), with the two atoms labelled H' and H". The lowest-energy atomic orbitals, 1s' and 1s", do not transform according to the symmetries of the molecule. However, the following symmetry adapted atomic orbitals do:

| 1s' – 1s" | Antisymmetric combination: negated by reflection, unchanged by other operations |

|---|---|

| 1s' + 1s" | Symmetric combination: unchanged by all symmetry operations |

The symmetric combination (called a bonding orbital) is lower in energy than the basis orbitals, and the antisymmetric combination (called an antibonding orbital) is higher. Because the H2 molecule has two electrons, they can both go in the bonding orbital, making the system lower in energy (hence more stable) than two free hydrogen atoms. This is called a covalent bond. The bond order is equal to the number of bonding electrons minus the number of antibonding electrons, divided by 2. In this example, there are 2 electrons in the bonding orbital and none in the antibonding orbital; the bond order is 1, and there is a single bond between the two hydrogen atoms.

He2

On the other hand, consider the hypothetical molecule of He2 with the atoms labeled He' and He". As with H2, the lowest energy atomic orbitals are the 1s' and 1s", and do not transform according to the symmetries of the molecule, while the symmetry adapted atomic orbitals do. The symmetric combination—the bonding orbital—is lower in energy than the basis orbitals, and the antisymmetric combination—the antibonding orbital—is higher. Unlike H2, with two valence electrons, He2 has four in its neutral ground state. Two electrons fill the lower-energy bonding orbital, σg(1s), while the remaining two fill the higher-energy antibonding orbital, σu*(1s). Thus, the resulting electron density around the molecule does not support the formation of a bond between the two atoms; without a stable bond holding the atoms together, the molecule would not be expected to exist. Another way of looking at it is that there are two bonding electrons and two antibonding electrons; therefore, the bond order is 0 and no bond exists (the molecule has one bound state supported by the Van der Waals potential).

Li2

Dilithium Li2 is formed from the overlap of the 1s and 2s atomic orbitals (the basis set) of two Li atoms. Each Li atom contributes three electrons for bonding interactions, and the six electrons fill the three MOs of lowest energy, σg(1s), σu*(1s), and σg(2s). Using the equation for bond order, it is found that dilithium has a bond order of one, a single bond.[20]

Noble gases

Considering a hypothetical molecule of He2, since the basis set of atomic orbitals is the same as in the case of H2, we find that both the bonding and antibonding orbitals are filled, so there is no energy advantage to the pair. HeH would have a slight energy advantage, but not as much as H2 + 2 He, so the molecule is very unstable and exists only briefly before decomposing into hydrogen and helium. In general, we find that atoms such as He that have full energy shells rarely bond with other atoms. Except for short-lived Van der Waals complexes, there are very few noble gas compounds known.

Heteronuclear diatomics

While MOs for homonuclear diatomic molecules contain equal contributions from each interacting atomic orbital, MOs for heteronuclear diatomics contain different atomic orbital contributions. Orbital interactions to produce bonding or antibonding orbitals in heteronuclear diatomics occur if there is sufficient overlap between atomic orbitals as determined by their symmetries and similarity in orbital energies.

HF

In hydrogen fluoride HF overlap between the H 1s and F 2s orbitals is allowed by symmetry but the difference in energy between the two atomic orbitals prevents them from interacting to create a molecular orbital. Overlap between the H 1s and F 2pz orbitals is also symmetry allowed, and these two atomic orbitals have a small energy separation. Thus, they interact, leading to creation of σ and σ* MOs and a molecule with a bond order of 1. Since HF is a non-centrosymmetric molecule, the symmetry labels g and u do not apply to its molecular orbitals.[21]

Quantitative approach

To obtain quantitative values for the molecular energy levels, one needs to have molecular orbitals that are such that the configuration interaction (CI) expansion converges fast towards the full CI limit. The most common method to obtain such functions is the Hartree–Fock method, which expresses the molecular orbitals as eigenfunctions of the Fock operator. One usually solves this problem by expanding the molecular orbitals as linear combinations of Gaussian functions centered on the atomic nuclei (see linear combination of atomic orbitals and basis set (chemistry)). The equation for the coefficients of these linear combinations is a generalized eigenvalue equation known as the Roothaan equations, which are in fact a particular representation of the Hartree–Fock equation. There are a number of programs in which quantum chemical calculations of MOs can be performed, including Spartan.

Simple accounts often suggest that experimental molecular orbital energies can be obtained by the methods of ultra-violet photoelectron spectroscopy for valence orbitals and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy for core orbitals. This, however, is incorrect as these experiments measure the ionization energy, the difference in energy between the molecule and one of the ions resulting from the removal of one electron. Ionization energies are linked approximately to orbital energies by Koopmans' theorem. While the agreement between these two values can be close for some molecules, it can be very poor in other cases.

Notes

- Prior to Mulliken, the word "orbital" was used only as an adjective, for example "orbital velocity" or "orbital wave function."[1] Mulliken used orbital as a noun, when he suggested the terms "atomic orbitals" and "molecular orbitals" to describe the electronic structures of polyatomic molecules.[2][3]

References

- orbital. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Mulliken, Robert S. (July 1932). "Electronic Structures of Polyatomic Molecules and Valence. II. General Considerations". Physical Review. 41 (1): 49–71. Bibcode:1932PhRv...41...49M. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.41.49.

- Brown, Theodore (2002). Chemistry : the central science. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-066997-0.

- Cotton, F. Albert (1990). Chemical applications of group theory (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley. pp. 102. ISBN 0471510947. OCLC 19975337.

- Albright, T. A.; Burdett, J. K.; Whangbo, M.-H. (2013). Orbital Interactions in Chemistry. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. ISBN 9780471080398.

- Hund, F. (1926). "Zur Deutung einiger Erscheinungen in den Molekelspektren" [On the interpretation of some phenomena in molecular spectra]. Zeitschrift für Physik (in German). Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 36 (9–10): 657–674. Bibcode:1926ZPhy...36..657H. doi:10.1007/bf01400155. ISSN 1434-6001. S2CID 123208730.

- F. Hund, "Zur Deutung der Molekelspektren", Zeitschrift für Physik, Part I, vol. 40, pages 742-764 (1927); Part II, vol. 42, pages 93–120 (1927); Part III, vol. 43, pages 805-826 (1927); Part IV, vol. 51, pages 759-795 (1928); Part V, vol. 63, pages 719-751 (1930).

- Mulliken, Robert S. (1 May 1927). "Electronic States and Band Spectrum Structure in Diatomic Molecules. IV. Hund's Theory; Second Positive Nitrogen and Swan Bands; Alternating Intensities". Physical Review. American Physical Society (APS). 29 (5): 637–649. Bibcode:1927PhRv...29..637M. doi:10.1103/physrev.29.637. ISSN 0031-899X.

- Mulliken, Robert S. (1928). "The assignment of quantum numbers for electrons in molecules. Extracts from Phys. Rev. 32, 186-222 (1928), plus currently written annotations". International Journal of Quantum Chemistry. Wiley. 1 (1): 103–117. doi:10.1002/qua.560010106. ISSN 0020-7608.

- Friedrich Hund and Chemistry, Werner Kutzelnigg, on the occasion of Hund's 100th birthday, Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 35, 573–586, (1996)

- Robert S. Mulliken's Nobel Lecture, Science, 157, no. 3785, 13-24. Available on-line at: Nobelprize.org

- Lennard-Jones, John (Sir) (1929). "The electronic structure of some diatomic molecules". Transactions of the Faraday Society. 25: 668–686. Bibcode:1929FaTr...25..668L. doi:10.1039/tf9292500668.

- Miessler, G.L.; Tarr, Donald A. (2008). Inorganic Chemistry. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-81-317-1885-8.

- Catherine E. Housecroft, Alan G. Sharpe, Inorganic Chemistry, Pearson Prentice Hall; 2nd Edition, 2005, p. 29-33.

- Peter Atkins; Julio De Paula. Atkins’ Physical Chemistry. Oxford University Press, 8th ed., 2006.

- Yves Jean; François Volatron. An Introduction to Molecular Orbitals. Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Michael Munowitz, Principles of Chemistry, Norton & Company, 2000, p. 229-233.

- Atkins, Peter; et al. (2006). Inorganic chemistry (4. ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-7167-4878-6.

- Bondybey, V.E. (1984). "Electronic structure and bonding of Be2". Chemical Physics Letters. 109 (5): 436–441. Bibcode:1984CPL...109..436B. doi:10.1016/0009-2614(84)80339-5.

- König, Burkhard (1995-02-21). "Chemical Bonding. VonM. J. Winter. 90 S., ISBN 0-19-855694-2. – Organometallics 1. Complexes with Transition Metal-Carbon σ-Bonds. VonM. Bochmann. 91 S., ISBN 0-19-855751-5. – Organometallics 2. Complexes with Transition Metal-Carbon π-Bonds. VonM. Bochmann. 89 S., ISBN 0-19-855813-9. – Bifunctional Compounds. VonR. S. Ward. 90 S., ISBN 0-19-855808-2. – Alle aus der Reihe: Oxford Chemistry Primers, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1994, Broschur, je 4.99 £". Angewandte Chemie (in German). 107 (4): 540. doi:10.1002/ange.19951070434.

- Catherine E. Housecroft, Alan G, Sharpe, Inorganic Chemistry, Pearson Prentice Hall; 2nd Edition, 2005, ISBN 0130-39913-2, p. 41-43.