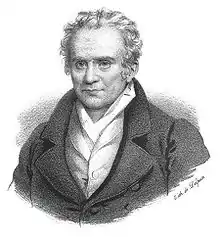

Gaspard Monge

Gaspard Monge, Comte de Péluse (9 May 1746[2] – 28 July 1818)[3] was a French mathematician, commonly presented as the inventor of descriptive geometry,[4][5] (the mathematical basis of) technical drawing, and the father of differential geometry.[6] During the French Revolution he served as the Minister of the Marine, and was involved in the reform of the French educational system, helping to found the École Polytechnique.

Gaspard Monge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 9 May 1746 |

| Died | 28 July 1818 (aged 72) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Descriptive geometry Transportation theory |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | mathematics, engineering, education |

| Notable students | Jean-Baptiste Biot[1] Charles Dupin Sylvestre François Lacroix Jean-Victor Poncelet[1] |

Biography

Early life

Monge was born at Beaune, Côte-d'Or, the son of a merchant. He was educated at the college of the Oratorians at Beaune.[5] In 1762 he went to the Collège de la Trinité at Lyon, where, one year after he had begun studying, he was made a teacher of physics[5] at the age of just seventeen.[7]

After finishing his education in 1764 he returned to Beaune, where he made a large-scale plan of the town, inventing the methods of observation and constructing the necessary instruments; the plan was presented to the town, and is still preserved in their library.[5] An officer of engineers who saw it wrote to the commandant of the École Royale du Génie at Mézières, recommending Monge to him and he was given a job as a draftsman.[5] L. T. C. Rolt, an engineer and historian of technology, credited Monge with the birth of engineering drawing.[8] When in the Royal School, he became a member of Freemasonry, initiated into ″L’Union parfaite″ lodge.[9]

Career

Those studying at the officer school were exclusively drawn from the aristocracy, so he was not allowed admission to the institution itself. His manual skill was highly regarded, but his mathematical skills were not made use of. Nevertheless, he worked on the development of his ideas in his spare time. At this time he came to contact with Charles Bossut, the professor of mathematics at the École Royale du Génie. "I was a thousand times tempted," he said long afterwards, "to tear up my drawings in disgust at the esteem in which they were held, as if I had been good for nothing better."[5]

After a year at the École Royale, Monge was asked to produce a plan for a fortification in such a way as to optimise its defensive arrangement. There was an established method for doing this which involved lengthy calculations but Monge devised a way of solving the problems by using drawings. At first his solution was not accepted, since it had not taken the time judged to be necessary, but upon examination the value of the work was recognised,[5] and Monge's exceptional abilities were recognised.

After Bossut left the École Royale du Génie, Monge took his place in January 1769, and in 1770 he was also appointed instructor in experimental physics.[7]

In 1777, Monge married Cathérine Huart, who owned a forge. This led Monge to develop an interest in metallurgy. In 1780 he became a member of the French Academy of Sciences; his friendship with chemist C. L. Berthollet began at this time.[5] In 1783, after leaving Mézières, he was, on the death of É. Bézout, appointed examiner of naval candidates.[5] Although pressed by the minister to prepare a complete course of mathematics, he declined to do so on the grounds that this would deprive Mme Bézout of her only income, that from the sale of the textbooks written by her late husband.[5] In 1786 he wrote and published his Traité élémentaire de la statique.[5]

1789 and after

The French Revolution completely changed the course of Monge's career. He was a strong supporter of the Revolution, and in 1792, on the creation by the Legislative Assembly of an executive council, Monge accepted the office of Minister of the Marine,[5] and held this office from 10 August 1792 to 10 April 1793, when he resigned.[7] When the Committee of Public Safety made an appeal to the academics to assist in the defence of the republic, he applied himself wholly to these operations, and distinguished himself by his energy, writing the Description Le l'art de Fabriquer Les canons and Avis aux ouvriers en fer sur la fabrication de l'acier.[5]

He took a very active part in the measures for the establishment of the Ecole Normale (which existed only during the first four months of the year 1795), and of the school for public works, afterwards the École Polytechnique, and was at each of them professor for descriptive geometry.[5] Géométrie descriptive. Leçons données aux écoles normales was published in 1799 from transcriptions of his lectures given in 1795. He later published Application de l'analyse à la géométrie,[5] which enlarged on the Lectures.

From May 1796 to October 1797 Monge was in Italy with C.L. Berthollet and some artists to select the paintings and sculptures being levied from the Italians.[5] While there he became friendly with Napoleon Bonaparte. Upon his return to France, he was appointed as the Director of the École Polytechnique, but early in 1798 he was sent to Italy on a mission that ended in the establishment of the short-lived Roman Republic.[5]

From there Monge joined Napoleon's expedition to Egypt, taking part with Berthollet[5] in the scientific work of the Institut d'Égypte and the Egyptian Institute of Sciences and Arts. They accompanied Bonaparte to Syria, and returned with him in 1798 to France.[5] Monge was appointed president of the Egyptian commission, and he resumed his connection with the École Polytechnique.[5] His later mathematical papers are published (1794–1816) in the Journal and the Correspondence of the École Polytechnique. On the formation of the Sénat conservateur he was appointed a member of that body, with an ample provision and the title of count of Pelusium[5] (Comte de Péluse), and he became the Senate conservateur's president during 1806–7. Then on the fall of Napoleon he had all of his honours taken away, and he was even excluded from the list of members of the reconstituted Institute.[5]

Napoleon Bonaparte stated Monge was an atheist.[10][11] His remains were first interred in a mausoleum in Le Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris and later transferred to the Panthéon in Paris.

A statue portraying him was erected in Beaune in 1849. Monge's name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the base of the Eiffel Tower.

Since 4 November 1992 the Marine Nationale operate the MRIS Monge, named after him.

Work

Between 1770 and 1790 Monge contributed various papers on mathematics and physics to the Memoirs of the Academy of Turin, the Mémoires des savantes étrangers of the Academy of Paris, the Mémoires of the same Academy, and the Annales de chimie, including "Sur la théorie des déblais et des remblais" (Mém. de l’acad. de Paris, 1781),[5] which is an elegant investigation of the problem with earthworks referred to in the title and establishes in connection with it his capital discovery of the curves of curvature of a surface.[5] It is also noteworthy to mention that in his Mémoire sur quelques phénomènes de la vision Monge proposed an early implicit explanation of the color constancy phenomenon based on several known observations.

Leonhard Euler, in his 1760 paper on curvature in the Berlin Memoirs, had considered, not the normals of the surface, but the normals of the plane sections through a particular normal, so that the question of the intersection of successive normals of the surface had never presented itself to him.[5] Monge's paper gives the ordinary differential equation of the curves of curvature, and establishes the general theory in a very satisfactory manner; the application to the interesting particular case of the ellipsoid was first made by him in a later paper in 1795.[5]

Monge's 1781 memoir is also the earliest known anticipation of linear optimization problems, in particular of the transportation problem. Related to that, the Monge soil-transport problem leads to a weak-topology definition of a distance between distributions rediscovered many times since by such as L. V. Kantorovich, Paul Lévy, Leonid Vaseršteĭn, and others; and bearing their names in various combinations in various contexts.

Another of his papers in the volume for 1783 relates to the production of water by the combustion of hydrogen. Monge's results had been anticipated by Henry Cavendish.[5] It was also in this time, from 1783 - 1784, that Monge worked with (Jean-François, Jean-Baptiste-Paul-Antoine, or Abbé Pierre-Romain) Clouet to liquefy sulfur dioxide by passing a stream of the gas through a U-tube sunken in a refrigerant mixture of ice and salt.[12] This made them the first to liquefy a pure gas.[13]

Selected publications

- 1781: Mémoire sur la théorie des déblais et des remblais De l'Imprimerie Royale.

- 1793: (with Alexandre-Théophile Vandermonde and Claude-Louis Berthollet) Avis aux ouvriers en fer, sur la fabrication de l'acier. Tome 8 (Advice to ironworkers, on the manufacture of steel)

- 1794: Description de l'art de fabriquer des canons (Description of the art of making cannon)

- 1795: Application d'analyse à la géométrie

- 1799: Géométrie descriptive. Leçons données aux écoles normales (Descriptive Geometry)

- 1807: Application de l'analyse à la géométrie, à l'usage de l'Ecole impériale polytechnique.

- 1810: (with Jean Nicolas Pierre Hachette) Traité élémentaire de statique, a l'usage des écoles de la Marine, chez Courcier, Imprimeur-libraire, pour les mathematiques, quai des Augustins, 1852 translation: An elementary treatise on statics.

See also

References

- Sooyoung Chang, Academic Genealogy of Mathematicians, World Scientific, 2010, p. 93.

- "Registres paroissiaux et/ou d'état civil : 16 janvier 1745 – 1746" [Parish and/or civil registers: January 16, 1745 – 1746] (in French). Archives of the Department of Côte-d'Or. p. 174/281. FRAD021EC 57/044. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "Monfredy (1845) to Mongé (1831)", Fichiers de l'état civil reconstitué [Reconstituted files of civil status] (in French), Paris Archives, p. 44/51, V3E/D 1076, retrieved 8 May 2018

- Albrecht Dürer and Guarino Guarini published works establishing the field before Monge.

- Arthur Cayley (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 709–710.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Gaspard Monge", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- J.J., O'Connor and; Robertson, E.F. "Gaspard Monge". School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- Rolt, L.T.C. (1957), Isambard Kingdom Brunel: A Biography, Longmans Green, LCCN 57003475.

- Alain Queruel, Les franc-maçons de l'Expédition d'Egypte (Editions du Cosmogone, 2012). Snezana Lawrence et Mark McCartney, Mathematicians and their Gods : Interactions between mathematics and religious beliefs (OUP Oxford, 2015). Emmanuel Pierrat et Laurent Kupferman, Le Paris des Francs-Maçons (Le Cherche Midi, 2013)

- "Napoleon replies: "How comes it, then, that Laplace was an atheist? At the Institute neither he nor Monge, nor Berthollet, nor Lagrange believed in God. But they did not like to say so." Baron Gaspard Gourgaud, Talks of Napoleon at St. Helena with General Baron Gourgaud (1904), page 274.

- Vincent Cronin (1983). The view from planet Earth: man looks at the cosmos. Quill. p. 164. ISBN 9780688014797.

Yet, sailing to Egypt, he had lain on deck, asking his scientists whether the planets were inhabited, how old the Earth was, and whether it would perish by fire or by flood. Many, like his friend Gaspard Monge, the first man to liquefy a gas, were atheists.

- Taton, Rene. “Some Details About The Chemist Clouet and Two of His Namesakes.” Review of the History of Sciences and Their Applications , vol. 5, no. 4, 1952, p. 359–67. JSTOR 23905084.

- Wisniak, Jaime (2003). "Louis Paul Cailletet—The liquefaction of the permanent gases" (PDF).

External links

Media related to Gaspard Monge at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gaspard Monge at Wikimedia Commons- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Gaspard Monge", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- An Elementary Treatise on Statics with a Biographical Notice of the Author (Biddle, Philadelphia, 1851).

- An elementary treatise on descriptive geometry, with a theory of shadows and of perspective (Weale, London, 1851).

- Géométrie descriptive. Leçons données aux Écoles normales, l'an 3 de la République; Par Gaspard Monge, de l'Institut national (Baudouin, Paris, 1798)

- Portrait of Gaspard Monge from the Lick Observatory Records Digital Archive, UC Santa Cruz Library's Digital Collections Archived 6 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Gaspard Monge (1789) "Mémoire sur quelques phenomenes de la vision." Annales de Chimie. Ser. 1, bk. 3 p. 131–147 – digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.