Monkeys in Japanese culture

The Japanese macaque (Japanese: 日本猿 Nihonzaru), characterized by brown-grey fur, a red face and buttocks, and a short tail, inhabits all of the islands in the Japanese archipelago except northernmost Hokkaido. Throughout most of Japanese history, monkeys were a familiar animal seen in fields and villages, but with habitat lost through urbanization of modern Japan, they are presently limited to mountainous regions. Monkeys are a historically prominent feature in the religion, folklore, and art of Japan, as well as in Japanese proverbs and idiomatic expressions.

The Japanese cultural meaning of the monkey has diachronically changed. Beginning with 8th-century historical records, monkeys were sacred mediators between gods and humans; around the 13th century, monkeys also became a "scapegoat" metaphor for tricksters and dislikable people. These roles gradually shifted until the 17th century, when the monkey usually represented the negative side of human nature, particularly people who foolishly imitate others. Japanese anthropologist Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney explains the idiom saru wa ke ga sanbon tarinai (猿は毛が三本足りない, "a monkey is [a human] minus three pieces of hair"): "The literal meaning of this saying is that the monkey is a lowly animal trying to be a human and therefore is to be laughed at.[1] However, the saying is understood by the Japanese to portray the monkey as representing undesirable humans that are to be ridiculed."

Language

Saru (猿) is the most common "monkey" word in the Japanese language. This Japanese kanji 猿 has on'yomi "Chinese readings" of en or on (from Chinese yuán), and kun'yomi "Japanese readings" of saru or Old Japanese mashi or mashira in classical Japanese literature. The archaic literary ete reading in etekō (猿公, "Mr. Monkey") is phonetically anomalous.

The etymologies of Japanese saru and mashira are uncertain. For saru (猿), Yamanaka[2] notes Ainu saro "monkey", which Batchelor[3] explains as, "from sara (a tail) and o (to bear), hence saro means 'having a tail'." Yamanaka suggests an etymology from Mongolian samji "monkey", transformed from sam > sanu > salu, with a possible ma- prefix evident in archaic Japanese masaru, mashira, and mashi pronunciations (of 猿). For mashira (猿), Yamanaka[4] cites Turner that Indo-Aryan markáta "monkey" derives from Sanskrit markaṭa (मर्कट) "monkey" (cf. meerkat), with cognates including Pali makkaṭa, Oriya mākaṛa, and Gujarti mākṛũ.[5]

Saru originally meant the "Japanese macaque" specifically, but was semantically extended to mean "simian", "monkey", "ape". The en or on Sino-Japanese reading is seen in words such as:

- shin'en (心猿, lit. "heart-/mind-monkey") (Buddhist) "unsettled; restless; indecisive"

- enjin (猿人 "monkey human") "ape-man"

- shinenrui (真猿類 "true monkey category") "simian"

- ruijinen (類人猿 "category human monkey") "anthropoid; troglodyte"

- oen (御猿, "great monkey") "menstruation", in comparison to a monkey's red buttocks

The native saru reading is used in many words, including some proper names:

- sarumawashi (猿回し, lit. "monkey revolving") "monkey trainer; monkey show"

- sarumane (猿真似, "monkey imitation") "superficial imitation; monkey see monkey do"

- sarujie (猿知恵, "monkey wisdom") "shortsighted cleverness"

- Sarugaku (猿楽, "monkey music") "a traditional form of comic theater, popular in Japan during the 11th to 14th centuries"

- Sarushima (猿島, "monkey island") "a small island in Tokyo Bay"

- Sarumino (猿蓑 "monkey straw-raincoat"), "a 1691 anthology of haiku poetry"

Personal names with the word saru "monkey" reflect semantically positive meanings of the monkey.[6] Japanese scholars consider Sarumaru Dayū (猿丸大夫) to be either "a legendary poet of the Genkei period (877–884)" or "a name given to a number of itinerant priest-poets who formed a group named Sarumaru". Sarumatsu (猿松) was the childhood nickname of the daimyō Uesugi Kenshin (1530–1578).

While most Japanese "monkey" words have positive denotations, there are a few pejorative exceptions.[7] One is a native Japanese term: yamazaru (山猿, "mountain/wild monkey") "country bumpkin; hick; hillbilly". Two are Sino-Japanese loanwords for foreign monkeys: shōjō (猩々 "orangutan") "a mythical red-faced, red-haired god of wine, who was always drunk and dancing merrily" or "heavy drinker; drunk" and hihi (狒々 "baboon") "satyr; lecher; dirty old man". This Japanese Shōjō legend derives from Chinese traditions that the xingxing (猩猩 "orangutan") is fond of wine.

Monkeys are a common trope in Japanese idioms:

- ken'en no naka (犬猿の仲, lit. "dog and monkey relationship") "a bad relationship; like cats and dogs"

- saru no shiri warai (猿の尻笑い, "monkey laughing at someone's buttocks") "laughing at someone's weakness while disregarding one's own weakness; the pot calling the kettle black"

- saru mo ki kara ochiru (猿も木から落ちる, "even monkeys fall from trees") "anyone can make a mistake"

The opaque idiom tōrō ga ono, enkō ga tsuki (蟷螂が斧猿猴が月, lit. "axes for a praying mantis, moon for a monkey") means,[8] "A praying mantis trying to crush the wheel of a cart with its forelegs (the axes) is portrayed as being as ridiculous as a monkey mistaking the reflection of the moon in the water for the moon itself and trying to capture it".

Chinese monkey lore

When the Japanese adapted Chinese characters to write Japanese, such as using Chinese yuan 猿 "gibbon; monkey" for saru "macaque; monkey", they concurrently adopted many Chinese monkey customs and traditions. Some notable examples are: the Year of the Monkey in the Chinese zodiac; the belief that "stable monkeys" will protect the health and safety of horses (see below); the traditional Chinese symbolic contrast between the superior, supernatural gibbon and the inferior, foolish macaque; and mythological monkeys like the Kakuen "a legendary monkey-man that abducts and rapes human women" (< Chinese jueyuan 玃猿) and the Shōjō "a god of wine with a red face and long, red hair" (< Chinese xingxing 猩猩 "monkey; orangutan").

Religion

Monkey deities are common among Japanese religious beliefs, including Shinto, notably Sannō Shinto, Kōshin, and Japanese Buddhism.

In ancient Shinto tradition, Sarutahiko Ōkami (猿田彦大神, lit. "monkey-field prince great god") or Sarutahiko (also pronounced Sarudahiko, Sarutabiko, or Sarudabiko) is a monkey-like God of Crossroads between heaven and earth. Sarutahiko Okami is worshipped at Tsubaki Grand Shrine in Mie and Ōasahiko Shrine in Tokushima.

The two earliest Japanese mytho-histories, the (712) Kojiki ("Record of Ancient Matters") and the (720) Nihongi ("Chronicles of Japan"), both record Sarutahiko. One Kojiki chapter mentions him,[9] "Now when this Deity Prince of Saruta dwelt at Azaka, he went out fishing, and had his hand caught by a hirabu shell-fish, and was drowned in the brine of the sea." The Nihongi has a more detailed myth about the Crossroad God Sarutahiko no Okami. When the Sun Goddess Amaterasu, said to be the ancestress of the Imperial House of Japan, decided to send her grandson Ninigi and other deities down to earth to govern, she first sent a scout to clear the way, who returned and reported encountering the fearsome Sarutahiko.

There is one God who dwells at the eight-cross-roads of Heaven, the length of whose nose is seven hands, the length of whose back is more than seven fathoms. Moreover, a light shines from his mouth and from his posteriors. His eye-balls are like an eight-hand mirror and have a ruddy glow like the Aka-kagachi.[10]

Amaterasu chose Ame-no-Uzume as the only god or goddess who could confront Sarutahiko and ask why he was blocking the crossroads between heaven and earth, and said:

"Thou art superior to others in the power of thy looks. Thou hadst better go and question him." So Ame no Uzume forthwith bared her breasts and, pushing down the band of her garment below her navel, confronted him with a mocking laugh. [Sarutahiko is shocked and explains that he is waiting to serve as guide for Ninigi] "I have heard that the child of Ama-terasu no Oho-kami is now about to descend, and therefore I have come respectfully to meet and attend upon him. My name is Saruta-hiko no Oho-kami".[11]

Sarutahito later marries Ame-no-Uzume. Ohnuki-Tierney lists three factors that identify Sarutahiko as a Monkey Deity: saru means "monkey", his features "include red buttocks, which are a prominent characteristic of Japanese macaques", and as macaques gather shellfish at low tide, the Kojiki says his hand got caught in a shell while fishing and "a monkey with one hand caught in a shell is a frequent theme of Japanese folktales".[12]

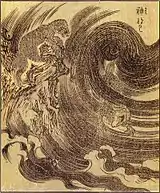

Another Shinto monkey myth concerns the God of Lightning Raijin who is accompanied by shape-shifting raijū (雷獣,"thunder beast") ball lightning that sometimes appeared as a monkey.

Sarugami (猿神, lit. "monkey god") was part of the Sannō Shintō sect, which was based upon the cult of the Mountain God Sannō (山王, "mountain king") and Tendai Buddhism. Sarugami was Sannō's messenger, and served as an intermediary between deities and humans. Sannō and Sarugami are worshipped at Hiyoshi Taisha Shrine in Ōtsu, Shiga.

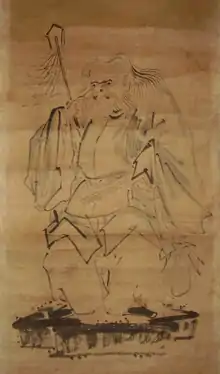

The Mountain and Monkey Gods Sannō and Sarugami became popular during the early Tokugawa or Edo period. Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who unified Japan in 1590 and ended the Sengoku period, was nicknamed Kosaru ("small monkey") or Saru ("monkey"), "not only because his face looked like a monkey's, but also because he eagerly sought identification with the monkey".[13] Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was the first shōgun (1603–1605) of the Tokugawa shogunate, "officially designated the Monkey Deity as the guardian of peace in the nation, and a festival for the deity was elaborately carried out in Edo" during his reign.[13] During this period, a genre of paintings illustrated the Monkey God as a messenger from the Mountain God, depicting him dancing during rice harvesting, or holding a gohei "a ritual wand with pendant paper streamers" ritualistically used by Shinto priests to summon the spirit of a deity. Thus, Ohnuki-Tierney says, "the monkey in these paintings is assigned the role of mediating between deities and humans, just as shamans and priests do".[13]

The role of monkeys as mediators is evident within the Japanese Kōshin folk religion. This eclectic belief system incorporates Daoist beliefs about the sanshi (三尸, "Three Corpses") "evil spirits that live in the human body and hasten death", Shinto Sarugami mythology (above), and Buddhist beliefs about simian gods such as the Vānara "a monkey-like humanoid" in the Ramayana. Shōmen-Kongō (青面金剛, "Blue-face Vajra" "a fearsome, many-armed, Kōshin guardian deity", who was supposedly able to make the Three Corpses sick and thus prevent them from reporting to Heaven, was commonly depicted with two or three monkey attendants.

In Daoist-Kōshin beliefs, the bodily Three Corpses keep records of their host's misdeeds, which they report to Heaven bimonthly on the night gengshen (Japanese kōshin) 庚申 "57th of the 60 (in the Chinese Sexagenary cycle)" while their human host is dreaming. But in a type of karmic loophole, someone who stays awake throughout that day and night can avoid receiving a shorter lifespan for their transgressions. The Japanese version of this custom, Kōshin-Machi (庚申待, "Kōshin Waiting"), became an all-night party among friends.

The sanzaru (三猿 "three monkeys") or English "Three Wise Monkeys" is a widely known example of monkeys in traditional Japanese culture. Their names are a pun between saru or vocalized zaru "monkey" and archaic -zaru "a negative verb conjugation": mizaru, kikazaru, iwazaru (見ざる, 聞かざる, 言わざる, lit. "don't see, don't hear, don't speak"). The Tōshō-gū shrine in Nikkō has elaborate relief carvings over the doors, including a famous representation of the Three Wise Monkeys. The Three Wise Monkeys also represent the Kōshin faith. They are displayed in the Yasaka Kōshin-dō Temple in Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto, dedicated to Shōmen Kongō, known by his nickname Kōshin-san (庚申さん) with the -san suffix for "Mr.; Ms.; Mrs.". This shrine also sells a kind of sarubobo (猿ぼぼ, "monkey baby") "red, faceless doll amulet" called the kukurizaru (くくり猿) believed to represent the good luck of monkeys.

Ohnuki-Tierney explains the meaning and the role of kōshin centered on mediation, "between temporal cycles, between humans and deities, and between heaven and earth. It is with this mediating deity that the monkey became associated, thereby further reinforcing the meaning of the monkey as mediator".[14]

Saeno kami (障の神, "border god"), later known as Dōsojin (道祖神, "road ancestor god"), is a Shinto tutelary deity of boundaries, which is usually placed at spatial boundaries, especially the boundary of a community, and is believed to protect people from epidemics and evil spirits. In popular belief, Saeno kami was merged with Shinto Sarutahiko, and later with Buddhist Jizō or Ksitigarbha "the bodhisattva of souls in hell and guardian of children". This amalgamation, says Ohnuki-Tierney, "resulted in stone statues of a monkey wearing a bib, which is a trademark of Jizō, a guardian Buddha of children".[15]

Literature

Monkeys are occasionally mentioned in early Japanese literature. Only one of the 4,500 poems in the (8th century) Man'yōshū mentions monkeys. Its author Ōtomo no Tabito "ridicules sober people for having faces as ugly as that of a monkey, while he justifies and praises drunks".[16] The (c. 787–824) Nihon Ryōiki collection of Buddhist setsuwa has a story about a female saint who first was mockingly called a saru "monkey" pretending to be something she is not, and later honorifically named with sari "ashes of the Buddha".[17]

Utsubozaru (靱猿, lit. "quiver monkey") The Monkey Skin Quiver is a kyōgen play in which a monkey dances with a lord who has just spared his life.

A Daimyō goes out hunting with his servant Taro Kaja, and on the way they meet a Monkey Trainer. The Daimyō wants to borrow the Monkey’s skin to cover his quiver. The Trainer, of course, refuses so the Daimyō gets angry and threatens to kill both the Trainer and the Monkey. The Trainer finally agrees, and asks for a few minutes to say goodbye. He also says that instead of shooting the Monkey with an arrow, which would harm the skin, he will kill it himself. He starts to strike the Monkey, and the Monkey mistakes his action for a signal to perform, so it grabs the stick and uses it as an oar. The Trainer begins to cry, the Daimyō asks the reason, and the Trainer replies that he has raised and trained the Monkey from the time it was born, so it is like a son to him. The Daimyō is greatly moved, and decides not to kill either the Monkey or the Trainer. In gratitude, the Monkey performs and the Trainer sings. The Daimyō presents his fan, sword, and even his own clothes to the Monkey Trainer; then he begins to dance and perform with the Monkey, thus ending on a happy note.[18]

The (c. 1596–1607) Inu makura or The Dog Pillow collection includes the description "red leaves dried out like a monkey's buttocks" (猿の尻木枯らししらぬ紅葉かな).

Folklore

Monkeys are a common theme in Japanese folktales and fairy tales.

The monkey is a malicious trickster in Saru Kani Gassen ("Battle of the Crab and the Monkey") over a rice-ball and a persimmon seed.[19]

In one widespread version, the monkey takes a rice ball from a crab in exchange for a persimmon seed, explaining to the crab that there is nothing left of a rice ball after its consumption, whereas a persimmon seed will grow and bear fruit. When the crab manages to grow the tree, which bears much fruit, the crab asks the monkey to fetch a persimmon. The monkey climbs up the tree and throws a persimmon at the crab, injuring or killing her, depending on the version. Eventually, the crab (or her children, in the version in which she is killed) and her sympathizers (a chestnut, a needle, a wasp, a mortar, dung, and so forth, depending upon the region) take revenge on the monkey.[20]

In Momotarō ("Peach Boy"), the hero is befriended by three talking animals, a monkey, a dog, and a pheasant.[21]

The monkey serves as a mediator in several folktales. The (13th century) Zatsudanshū has a story about a diligent man and a lazy man who once lived at the foot of a mountain.

The hard-working man worked in the field from early morning till evening to grow soybeans and red beans. One day he became tired and fell asleep, whereupon monkeys came and thought he was a Buddha. They gave him yams and other offerings and went back to the mountain. The man took the offerings home. Upon hearing this story, the wife of the lazy man urged her husband to do the same. The monkeys carried him across the river to ensconce him there. While they were carrying him on their arms, the monkeys said, "We should raise our hakama [a skirt-like garment for men]", and they stroked their fur to imitate the gesture of raising the hakama. Upon seeing this, the man laughed. The monkeys said that he was a man, instead of a Buddha, and threw him into the river. He was drenched, swallowed a great deal of water, and narrowly escaped his death. Upon hearing of the incident, his wife became enraged. "One should never engage in superficial imitation of others".[22]

These monkeys act as "sacred mediators who on behalf of the Mountain Deity punish a lazy man and his wife for engaging in superficial imitation of their neighbors, while they themselves are imitating humans". Saru Jizō (猿地蔵, "Monkey Jizo") was a later version of this tale in which the monkeys mistake both men for a Jizō Buddha rather than simply a Buddha.[6]

Some folktales portray the monkey as a trickster who tries to outsmart others. Take for instance, Kurage honenashi (水母骨なし) "Boneless Jellyfish".[23] When the Dragon King hears that eating a live monkey's liver is the only medicine that will save his queen from dying, he sends his trusted servant fish to cross the ocean, go to the monkey-land, and convince a live monkey to return to the dragon-land. While they are traveling across the ocean, the monkey learns that the king will cut out his liver, and tells the fish that he left his liver hanging on a tree in monkey-land, where they return to find the tree empty. When the fish swims back to dragon-land and reports what happened, the king realizes the monkey's deception, and orders his officers to break every bone in the fish's body and beat him to a jelly, which is why jellyfish do not have bones.

Art

Monkeys are a traditional motif in Japanese art.

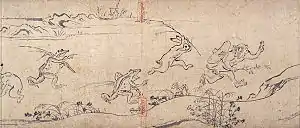

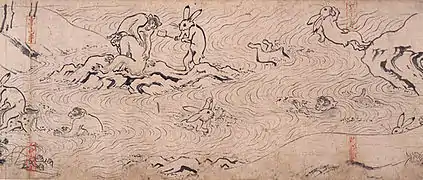

The (12th and 13th centuries) Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga picture scrolls depict anthropomorphic animals, notably monkeys and rabbits bathing, monkeys and rabbits wrestling, and a monkey thief running from rabbits and frogs with sticks.

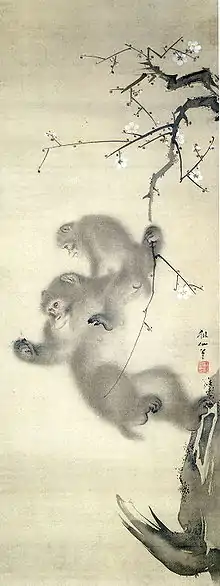

Since the gibbon's habitat did not include Japan, the Japanese were unfamiliar with its long-limbed, tailless appearance until the 13th century, mainly through the paintings of the Song dynasty Zen priest and artist Muqi (牧溪, Japanese Mokkei 牧谿), who immigrated to Kyoto. Muqi's "work was eagerly studied in Japan, and a number of painters adopted his calligraphic style of rendering the gibbon".[24] Muqi's masterful "Guanyin", "Monkeys" (depicting a mother and infant gibbons), and "Crane" scrolls, which are one of the National Treasures of Japan, became the model for drawing gibbons. Many prominent Edo-period (1603–1867) painters, including Hasegawa Tōhaku, Kusumi Morikage, and Kanō Tsunenobu, who had never seen gibbons, depicted them following the Bokkei-zaru (牧谿猿) "Muqi's gibbons" artistic tradition.[25] Mori Sosen (1747–1821), who was the "undisputed master"[26] of painting the Japanese macaque, influenced later paintings of gibbons, which, in the absence of live models, were sometimes represented with the macaque's red face and brown fur.

Muqi's gibbons were usually drawn in nature, while Japanese macaques were often depicted among humans or human-made objects. Ohnuki-Tierney notes that gibbons "represented nature, which in folk Shintoism signified deities" and also "represented the Chinese art tradition (kanga), which in turn represented the Chinese, who were then the most significant foreigners".[27] She posits four levels symbolized by Japanese macaque/gibbon contrast: Japanese/foreigners, humans/deities, culture/nature, and self/other..[28]

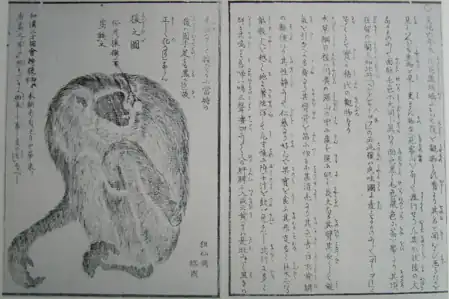

The Kenkadō zarsuroku (蒹葭堂雜錄, 1856), by Kimura Kenkadō (木村蒹葭堂), records a gibbon imported to Japan, and includes a calligraphic drawing by Mori Sosen. In 1809, a gibbon was exhibited in the Dōtonbori red-light district of Osaka.

Although we have heard the word "gibbon" [en or saru 猨] since olden times, and seen pictures of him, we never have seen a live specimen, and therefore a large crowd assembled to see this gibbon. Generally he resembles a large macaque, and figure and fur are very similar. The face is black, the fur grey with a touch of brown. The Hollander "Captain" Hendrik Doeff [i.e., the Dutch Dejima trading post commissioner, Hendrik Doeff] who was then staying here said that this gibbon occurs on the island of Java where it is called "wau-wau". Truly an extraordinary sight![29]

Van Gulik suggests this Indonesian owa jawa "silvery gibbon" specimen was brought to Japan on a Dutch ship.

As the Monkey is part of the Chinese zodiac, which has been used for centuries in Japan, the creature was sometimes portrayed in paintings of the Edo period as a tangible metaphor for a particular year. The 19th-century artist and samurai Watanabe Kazan created a painting of a macaque.

During the Edo period, numerous netsuke, tsuba, and other artifacts were decorated with monkeys.

Cuisine

Eating monkey meat, which is a long-standing tradition in China, is uncommon in Japanese culture. Archaeological excavations have found monkey bones at sites dated from the hunting-gathering Jōmon period (c. 14,000–300 BCE) but not at sites from the agricultural Yayoi period (300 BCE-250 CE) and later. Besides being a source of food for the hunters, monkeys were a menace to farmers because they stole crops. Since the avoidance of monkey meat infers people seeing the proximity between monkeys and themselves, Ohnuki-Tierney concludes that Japanese beliefs about the "semideified status and the positive role of mediation between humans and deities" began in the Yayoi era.[30] Buddhist thought affected some Japanese attitudes toward monkeys; the Nihongi records that in 676, Emperor Tenmu issued a law the prohibited eating the meat of cattle, horses, dogs, monkeys, and chickens.[31] Even today, in the regions northeast of the Ryōhaku Mountains in Ishikawa Prefecture, "hunters observe no taboo in regard to monkey hunting, while those in the regions southwest of the mountain range observe numerous taboos".[32]

Horse guardian and healer

Following Chinese traditions that keeping a monkey in a stable would protect horses from diseases and accidents, the Japanese gave monkeys the important role of horse guardians, honorifically called the umayagami (厩神, "stables god"). This belief gave rise to two related practices.[33] First, both samurais and farmers covered their quivers with monkey hides so as to harness the protective power of the monkey over horses. Second, people drew horse pictures on ema (絵馬, lit. "picture horse") "votive wooden plaques" and offered them at Shinto shrines to ensure the health of their horses. "A large number of ema from various historical periods and regions of Japan depict monkeys pulling horses, providing rich evidence that the monkey functioned as guardian of horses." Monkeys were believed to scare away other animals and pests, and farmers in southern Japan fed monkeys in order to protect their fields.

The Kōjien dictionary says sarumawashi (猿回し) "monkey trainer" derives from saruhiki (猿曳き "monkey puller"), and quotes Japanese folklore scholar Kunio Yanagita that trainers were also originally bai (馬医 "horse doctors"). Yanagita also described the ancient Tōhoku region custom of umayazaru (厩猿 "stables monkey") that was mentioned in the Ryōjin Hishō and Kokon Chomonjū. This "stable monkey" originally referred to monkeys living in stables in order to protect the health and safety of horses, and later referred to putting up a symbolic monkey skull, paw, or picture.

The monkey's role in healing was not limited to horses, but also extended to monkey deities and monkey medicines.[34] The supernatural beings associated with the monkey—kōshin, saeno kami, and jizō—"are all assigned the role of healing." Many parts of the monkey's body have been used as medicine, since at least the 6th century. "Even today, a charred monkey's head, pounded into powder, is taken as medicine for illnesses of the head and brain, including mental illnesses, mental retardation, and headaches." Furthermore, representations of monkeys are believed to have healing powers. Three Wise Monkey figurines are used as charms to prevent illnesses. Kukurizaru "small stuffed monkey amulets" are thought to be "efficacious in treating various other illnesses, as well as childbirth."

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Kukuizaru and a monkey statue at Yasaka Kōshin-dō.

Kukuizaru and a monkey statue at Yasaka Kōshin-dō. Monkeys and rabbits bathing, Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga, c. 12th century.

Monkeys and rabbits bathing, Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga, c. 12th century. Macaque painting by Watanabe Kazan, 19th century.

Macaque painting by Watanabe Kazan, 19th century. Monkeys in a persimmon-tree, Mori Sosen.

Monkeys in a persimmon-tree, Mori Sosen. Monkeys on a limb, Mori Sosen.

Monkeys on a limb, Mori Sosen. Iron, gold, and silver box showing a monkey and octopus tug-of-war.

Iron, gold, and silver box showing a monkey and octopus tug-of-war. Edo-era tsuba sword guard depicting adult and young monkeys.

Edo-era tsuba sword guard depicting adult and young monkeys. Edo-era lacquer inro container showing 115 anthropomorphic monkeys.

Edo-era lacquer inro container showing 115 anthropomorphic monkeys. Waterfall and monkeys, Shibata Zeshin, 1872.

Waterfall and monkeys, Shibata Zeshin, 1872. Gibbon reaching for the moon's reflection, Ohara Koson, 1926

Gibbon reaching for the moon's reflection, Ohara Koson, 1926 Saru dango (猿団子, "monkey dango") of three Snow Monkeys.

Saru dango (猿団子, "monkey dango") of three Snow Monkeys.

References

- Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Translated by Aston, William George. Kegan Paul. 1896. 1972 Tuttle reprint.

- van Gulik, Robert Hans (1967). The gibbon in China: An essay in Chinese animal lore. E. J. Brill.

- Keene, Donald (2006), Frog In The Well: Portraits of Japan by Watanabe Kazan 1793–1841, Columbia University Press.

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko (1989). The Monkey as Mirror: Symbolic Transformations in Japanese History and Ritual. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691028460.

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko (1990a), "Monkey as Metaphor? Transformations of A Polytropic Symbol in Japanese Culture", Man (N.S.) 25:399–416.

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko (1990b), "The Monkey as Self in Japanese Culture", in Culture Through Time , Emikio Ohnuki-Tierney, ed., Stanford Univ. Press, 128–153.

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko (1984), "Monkey Performances – A Multiple Structure of Meaning and Reflexivity in Japanese Culture", in Text, Play and Story, E. Bruner, ed., American Ethnological Society, 278–314.

- Okada Yuzuru (1951), Netsuke: A Miniature Art of Japan, Japan Travel Bureau.

- Ozaki, Yei Theodora (1903). The Japanese Fairy Book. rchibald Constable.

Footnotes

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, pp. 59–60.

- Yamanaka Jōta (山中襄太) (1976), Kokugo gogen jiten (国語語源辞典), Vol. 1, Azekura shobo (校倉書房). p. 253 (in Japanese).

- Batchelor, John (1905), An Ainu-English-Japanese Dictionary, Methodist Publishing House. p. 22.

- Yamanaka Jōta (山中襄太) (1985), Kokugo gogen jiten (国語語源辞典), Vol. 2, Azekura shobo (校倉書房). p. 410 (in Japanese).

- Turner, Ralph Lilley (1999), A Comparative Dictionary of the Indo-Aryan Languages, Motilal Banarsidass Publishe. |at=p. 568.

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, p. 52.

- Carr, Michael (1993), "'Mind-Monkey' Metaphors in Chinese and Japanese Dictionaries," International Journal of Lexicography 6.3:149–180 (p. 167).

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, p. 64.

- Chamberlain, Basil H., tr. 1919. The Kojiki, Records of Ancient Matters. Asiatic Society of Japan. 2005 Tuttle reprint. p. 139.

- Tr. Aston 1896, p. 77.

- Tr. Aston 1896, p. 77.

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, pp. 42–3.

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, p. 44.

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, p. 46-7.

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, p. 48.

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, p. 53.

- LaFleur, William R. (1983), The Karma of Words: Buddhism and the Literary Arts in Medieval Japan, University of California Press. pp. 42, 169.

- Sebeok, Thomas Albert (1986), I Think I am a Verb: More Contributions to the Doctrine of Signs, Springer-Verlag. p. 120.

- Ozaki 1903, pp. 205–15.

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, p. 54.

- Ozaki 1903, pp. 244–61.

- Tr. .Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, p. 51.

- Chamberlain, Basil H. (1887), "The Silly Jelly-fish", Kobunsha.

- van Gulik 1967, p. 97.

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, p. 26.

- van Gulik 1967, p. 98.

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, p. 27.

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, pp. 28–9.

- Tr. van Gulik 1967, p. 98.

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, p. 56.

- Aston 1896, p. 329.

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, p. 57.

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, p. 48–9.

- Ohnuki-Tierney 1989, p. 50.

External links

- Monkey in Japan, Mark Schumacher