Montecalvo Irpino

Montecalvo Irpino is a town and comune in the province of Avellino, Campania, southern Italy.

Montecalvo Irpino | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Montecalvo Irpino | |

| |

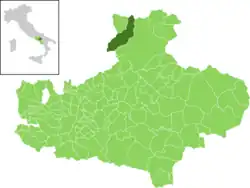

The municipality of Montecalvo Irpino within the province of Avellino | |

Location of Montecalvo Irpino | |

Montecalvo Irpino Location of Montecalvo Irpino in Italy  Montecalvo Irpino Montecalvo Irpino (Campania) | |

| Coordinates: 41°11′48″N 15°2′3″E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Campania |

| Province | Avellino (AV) |

| Frazioni | Corsano, Malvizza mud volcanoes |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mirko Iorillo |

| Area | |

| • Total | 53.53 km2 (20.67 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 623 m (2,044 ft) |

| Population (1 January 2017)[2] | |

| • Total | 3,663 |

| • Density | 68/km2 (180/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Montecalvesi |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 83037 |

| Dialing code | 0825 |

| Patron saint | St. Felix |

| Saint day | 30 August |

| Website | Official website |

Located upon a hill oversighting Ufita Valley, the town is known for its bread (pane di Montecalvo), which is granted PAT quality mark, and Irpinia - Colline dell'Ufita DOP olive oil.

In the countryside there are the ruins of Corsano fortified village, devastated by 1656 plague and since abandoned, and Malvizza bullae, the widest mudpot field in Southern Italy.

Geography

Territory

Montecalvo Irpino is located in the northern sector of the province of Avellino, on the border with Benevento. The municipality, built at an elevation of 2,044 ft (623 m) MSL, upstream of the confluence between the Miscano stream and the Ufita River, is part of the mountain community of Ufita. Its land is mostly clayey and tuffaceous,[3] and is mainly mountainous. The municipal countryside covers an area of 20.67 sq mi (53.50 km2), with an altitude ranging from 151 to 700 m above sea level, with an excursion of 549 m.[4]

Typical of the rural territory of Montecalvo Irpino are the Malvizza Mud Volcanoes, that is the mud volcanoes that sprout in the middle of the Miscano valley.[5]

Climate

Thanks to its moderately hilly location, the climate of Montecalvo Irpino is generally temperate with moderate rainfall.

Origins of the name

According to many scholars, the first part of the town's name derives from the Latin mons calvus, or "rocky mountain, without trees", according to others instead from mons galbus, or "yellow mountain" for the color of the tuff or broom flowers present in the area.[6] A third interpretation, much less likely, would derive the term "calvo" from Calvia, a Roman clan that had some possessions in the area.

The last part of the town's name, "Irpino", identifies the historical-geographical district in which it lies (Irpinia) to distinguish it from the numerous others with the same or similar names.

History

A stable presence of the area since Roman times is attested by the discovery of wall structures referable to a rustic villa in Tressanti (on the border with Ariano Irpino), as well as by archaeological material from a necropolis and areas reported in various other locations in the municipal area.[7]

The first historical notice of Montecalvo is contained in a document of 1096, which refers to the sending of about sixty armed men from that area in the expedition to the Holy Land at the will of William II of Sicily.[7]

The chronicle of Alessandro Telesino recalls that in 1137 King Roger II, Norman ruler at war with the Count of Avellino, camped at the foot of the castle of Montecalvo.[8]

In the Catalogus Baronum it appears that the first feudal family was that of the Potofranco. Following the destruction caused by the troops of Manfredi di Svevia, the feud was first granted to the noble Matteo Diletto (1276) and then donated by King Charles I of Anjou to Giovanni Mansella of Salerno.[9]

From the end of 1300 Montecalvo followed the events of the county Ariano Irpino, to which it remained aggregated during the governments of de Sabran, Sforza and Guevara. The violent earthquake of 1456 caused the sinking of part of the town (probably in the Fosso Palumbo) and the subsequent urban expansion outside the walls, which were never rebuilt. In 1486, the feud came directly under the government of the Royal Court and eight years later it was sold, together with the fiefs of Corsano and Pietrapiccola, by King Alfonso II of Aragon to Ettore Pignatelli, Duke of Monteleone and Viceroy of Sicily. He managed the revenues from the territory until 1501, when the town was sold to Alberico Carafa first Duke of Ariano.[9]

During the brief domination by the French, which began in the same year 1501, the lord of Montecalvo was Pietro del Rohan, marshal of France and loyal to King Ludovico. Re-established Spanish power, King Ferdinand the Catholic restored the duchy of Ariano which, with Montecalvo, returned to Alberico Carafa. In 1505 Montecalvo was donated by him to his second son, Sigismondo, who in 1525 was appointed count.[9]

For almost a century, the Carafa administered the county of Montecalvo, until, in 1594, it was purchased by Carlo Gagliardi, who in 1611 boasted the title of duke. At his death in 1624, the duchy returned to the Pignatelli family, to whom it belonged until 1806, the year of the abolition of feudal rights in southern Italy.[9]

In the Bourbon era, Montecalvo was one of the most active centers of the Carbonari in Irpinia. On the occasion of the constitutional motions of 1820-1821 from Montecalvo, in fact, many volunteers left and fought against the Austrians in the battle of Antrodoco, under the command of Guglielmo Pepe.[10]

At the time of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the municipality was the capital of the district (with jurisdiction over the municipalities of Casalbore and Sant'Arcangelo Trimonte) within the district of Ariano. Subsequently, in the post-unification era, Montecalvo was instead the capital of the district (with jurisdiction over the same two municipalities) within the district of Ariano di Puglia.

In the first decades of the twentieth century in Montecalvo Irpino, the socialist ideals were widely spread among intellectuals and laborers, fighting for better living conditions. Even during the Ventennio, in fact, anti-fascism remained active, especially by historical exponents of local socialism, such as the pharmacist Pietro Cristino and the confined politicians from other regions (such as the communist Concetto Lo Presti).[11][12][13] In 1944, the local branch of the Italian Communist Party was founded, named after Giuseppe Cristino (volunteer who fell in the Spanish Civil War fighting in the International Brigades).[11][12][13] In 1946, the alliance between socialists and communists, sanctioned by the creation of the frontist list of "La Spiga", managed to win the first post-war administrative elections, electing the socialist Pietro Cristino as mayor. On the occasion of the institutional referendum of 2 June 1946 Montecalvo Irpino was one of the 14 municipalities in the province of Avellino in which the Republic won, and among them it was the one in which the Republic obtained the highest percentage of votes (62%).[14]

Over the centuries the country has been scourged by several earthquakes. In particular, the earthquakes of 1688 and 1962 destroyed several churches, caused serious damage to the ducal palace and the church of Santa Maria Assunta, whose bell tower was also demolished in 1981.[9]

Monuments and places of interest

Religious architecture

- Convent of Sant'Antonio da Padova

Located at the entrance of the village, it was opened for worship in 1631 after more than a century from the issue of the papal bull authorizing its construction. Damaged several times by earthquakes, it was completely rebuilt after the earthquake of 1962 which caused serious structural damage but not the loss of many of the works of art that were therefore saved and transferred to the new structure; prominent among them are two large confessionals in decorated wood of the late eighteenth century. Since its origins, the convent has hosted the Franciscan Friars Minor who also take care of the adjacent Oasi Maria Immacolata.[15]

- Church of Santa Maria Assunta

Now called Santa Maria Maggiore, it was completed in 1428 at the time of Francesco Sforza (Duke of Ariano and future Duke of Milan). Remarkable inside are the high altar consisting of a monoblock of granite and the baptismal font dating back to the fifteenth century but supported by two ancient capitals of barbarian art.[9]

- Church of San Pompilio Maria Pirrotti

Built at the beginning of the twentieth century in what was originally the ground floor of Palazzo Pirrotti, it was consecrated in 1937. Inside there are several works of art, including a wooden statue from the eighteenth century, but what is remarkable above all else is the adjacent archive-shrine that houses many relics that belonged to San Pompilio Maria Pirrotti, a native of the place.[9][16]

Military architecture

- The Castle

Located at the highest point of the village, it underwent many transformations over the centuries, with the destruction of the original towers and the addition of the ramparts on the northwest side. After the earthquake of 1456, it was destined to become a noble residence, of which the imposing structures of the ground floor and a few ruins of the upper floors remain.[17][16]

- Santa Caterina Hospital

Saint Catherine Hospital (Ospedale Santa Caterina) was built around 1200 along one of the routes of the Via Francigena and dedicated to Saint Catherine of Alexandria. It was originally a fortified structure intended for the reception of crusaders, pilgrims, and the sick. In 1518 the hospital, together with the adjacent church of Santa Caterina (no longer existing), came under the management of Blessed Felice da Corsano. Of the ancient structure, only the imposing ruins along via Lungara Fossi remain.[9][16]

Civil architetture

- Palace de Cillis

The Palace de Cillis (Palazzo de Cillis), bearing the name of the De Cillis family, is located along Corso Umberto and is characterized by its grandeur. Above all, the stone portal formed by a double series of twenty panels in finely chiselled white stone is especially noteworthy. Inside the palace there is the chapel of Santa Maria della Neve (or del Soccorso) with the characteristic majolica floor, perhaps dating back to the seventeenth century.[9] The De Cillis family is originally from Spain, present with several branches in Puglia and Campania, with several properties in Pago Veiano and Montecalvo Irpino.[18]

- The Trappeto District

The Trappeto District (Rione Trappeto) is a rocky district composed of caves dug into the natural tuff by refugees from Corsano, a nearby village desolated by the devastating plague of 1656. The few survivors took refuge in Montecalvo where they constituted a sort of village between the cliffs and caves.[9] Note that the name "Trappeto" derives from the vernacular term trappito ("oil mill" in the Irpinian dialect)

Sekoma

Located in the Municipal Plaza (Piazza Municipio), it consists of a massive block of stone measuring 148 x 67 x 64 cm and weighing a few tons, it is equipped with hemispherical recesses at the top and some holes drilled inside. Dating back in all probability to the third or second century BC, it is a rare legal sample of units of measurement of weight and capacity in Hellenistic times. It is also known by the Latin term of mens ponderaria (public weighbridge).[19]

Corsano

Corsano is an ancient medieval village abandoned after the plague of 1656 (Naples Plague (1656)) eradicated most of the inhabitants. The ruins of the castle are preserved.

The Devil's Bridge

Also known as the "bridge of Santo Spirito", it is the ruins of a Roman bridge along the ancient Via Traiana. It rises along the river Miscano in the Santo Spirito district between Casalbore and Montecalvo Irpino.[9][16][20][21][22]

Mud Volcanos of Malvizza

Located along the provincial road that leads to Castelfranco in Miscano, the Malvizza Mud Volcanoes consist of the largest complex of mud volcanoes in the southern Apennines. Nearby there is the ancient tavern of the Duke, along the Pescasseroli-Candela sheep track.[9][16]

Notable People

- Saint Pompilio Maria Pirrotti

Saint Pompilio Maria Pirrotti (San Pompilio Maria Pirrotti) of the Pious Schools (Scuole Pie) was born in Montecalvo Irpino on September 29, 1710, died in Campi Salentina on July 15, 1766, was beatified in 1890, and canonized on March 19, 1934.[23][16]

- Blessed Felice Pomes of Corsano

Blessed Felice Pomes, was born in Corsano, now a district of the Municipality of Montecalvo Irpino, around the first half of the fifteenth century and died on September 20, 1526. Four days after his death, according to the customs of the time, he was "declared" immediately Blessed.[23][16]

References

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- All demographics and other statistics from the Italian statistical institute (Istat); Dati - Popolazione residente all'1/5/2009

- "Il bacino di Ariano-Benevento" (PDF) (in Italian). Università Federico II di Napoli.

- "Comune di Montecalvo Irpino" (in Italian).

- "Bolle Malvizza" (in Italian).

- "Comune di Montecalvo Irpino (AV)" (in Italian). 25 November 2022.

- "Montecalvo Irpino" (in Italian).

- AA.VV. (1990). Generoso Procaccini (ed.). I Dauni-Irpini (in Italian). Napoli. p. 136.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Archeoclub d'Italia (sede di Casalbore) (1995). Giovanni Bosco and Maria Cavalletti (ed.). Progetto itinerari turistici Campania interna - La Valle del Miscano (in Italian). Vol. 1. Regione Campania (Centro di Servizi Culturali - Ariano Irpino). Avellino. pp. 109–159.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Giovanni Bosco; Maria Cavalletti (March 2011). We were there too... The Unification of Italy in Irpinia and surroundings (in Italian). Montecalvo Irpino.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Una famiglia antifascista: Pietro e Giuseppe Cristino" (in Italian). 29 December 2022.

- "Giuseppe and Pietro Cristino" (in Italian).

- "The Death of Antonio Smorto" (in Italian).

- Alfonso Caccese, The Republican mayors of Montecalvo, Montecalvo Irpino 2006

- "Convento S.Antonio di Padova - Montecalvo Irpino" (in Italian).

- "Magica Irpinia: Montecalvo Irpino" (in Italian). 8 June 2020.

- "Castello" (in Italian).

- "Discovering Palazzo De Cillis" (in Italian).

- "Sekoma" (in Italian).

- Lorenzo Giustiniani, ed. (1797). Dizionario Geografico ragionato del regno di Napoli (in Italian). Vol. 1. Napoli: Tipografia di Vincenzo Manfredi. p. 197.

- Thomas Ashby; Robert Gardner (1916). "The Via Traiana". Papers of the British School at Rome. Rome: British School at Rome. 8 (5): 104–171. doi:10.1017/S0068246200005481. ISSN 0068-2462. S2CID 129857079.

- Vittorio Galliazzo (1995). I ponti romani. Catalogo generale (in Italian). Vol. 2. Treviso: Canova Edizioni. p. 112. ISBN 88-85066-66-6.

- "San Pompilio Maria Pirrotti" (in Italian).