Mines of Paris

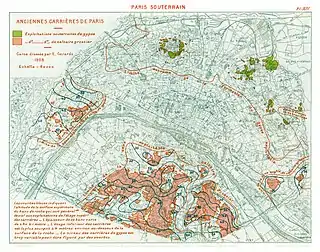

The mines of Paris (French: carrières de Paris – "quarries of Paris") comprise a number of abandoned, subterranean mines under Paris, France, connected together by galleries. Three main networks exist; the largest, known as the grand réseau sud ("large south network"), lies under the 5th, 6th, 14th and 15th arrondissements, a second under the 13th arrondissement, and a third under the 16th, though other minor networks are found under the 12th, 14th and 16th for instance. The commercial product was Lutetian limestone for use as a building material, as well as gypsum for use in "plaster of Paris".

Exploring the mines is prohibited by the prefecture and penalised with large fines. Despite restrictions, Paris's former mines are frequently toured by urban explorers known popularly as cataphiles.

A limited part of the network—1.7 kilometres (1.1 mi) in length—has been used as an underground ossuary, known as the catacombs of Paris, some of which can be toured legally. The catacombs were temporarily closed between September and 19 December 2009 due to vandalism,[1] after which they could be legally visited again from the entrance on Place Denfert-Rochereau. The entire subterranean network is commonly but mistakenly referred to as "the catacombs".

Formation of the minerals mined in Paris

Paris lies within the Paris Basin, a geological bowl-like shape created by millennia of sea immersion and erosion.[2] Much of north-western France spent much of its geological history as a submerged sea water coastline, but towards our era, and the formation of our continents as we know them, the then relatively flat area that would become the Paris region became increasingly elevated. The region was alternately invaded and sculpted by both sea water, inland sea water lagoons and fresh water, in addition to above-water air and river erosion. These cycles produced a rich and varied geological strata containing many minerals that would become a source of growth and wealth for the Paris region.[3]

Mineral formation

The region of Paris has spent most of its geologic history under water, which is why it has such varied and important accumulations of sedimentary minerals, notably Lutetian Limestone.[3]

The Paris area was a relatively flat sea-bottom during the early Cretaceous period: first in a deep-sea environment, then under a more agitated near-shoreline sea towards the end of the same period, Paris's largely silica-based sedimentary deposits became, under the action of pressure and the carbonic acid content of seawater, a thick deposit of clay. The invasion of calcium-rich seas then covered this with an even more important layer of chalk. Paris emerged from the sea towards the end of the Cretaceous Period, and later Palaeozoic-era continental shifts, particularly the Variscan orogeny geological upheavals, created a series of hills and valleys throughout the Parisian basin, creating conditions ideal for the mineral deposits that would appear during the next eras.

After a long period above sea level that ended towards the Cenozoic era, Paris began a period of alternation between sea and land environments. Paris was the middle of a shoreline of bays and lagoons of still seawater, an environment perfect for the silica-based sea life abundant then. As sea creatures died and settled to the lagoon bottom, their shells mixed with the deposits already present; pressure from additional sea-life sedimentation and the chemical action of the water transformed the result into a sedimentary stone quite particular to the Paris area, calcaire grossier (calcaire lutécien in more modern publications). Paris's most important deposits of this stone occurred during the Eocene epoch's Lutetian age; in fact, the age itself is named for the sedimentary activity in the Paris region, as Lutetia was the city's name during Roman times.

Paris's next important mineral deposit came with the Bartonian age. After a period of land-sea alternation that brought layers of sand and low-quality calcaire grossier, the sea regressed again to return only occasionally to refill lagoons with seawater. The result was stagnating pools of evaporating seawater; the salts of these, mixed with other organic matter and mineral deposits, crystallised into the calcium sulphate composition that is gypsum. This evaporation cycle occurred several times during this age, creating several layers of gypsum divided by layers of mineral left by the sea's brief return. In all, Parisian gypsum deposits are divided into four "masses", with the last appearing, the haute masse, being the most important and most exploited in Parisian history. Gypsum, an evaporite mineral, is known for its fragility against freshwater invasion, re-dissolving quite readily.

The sea returned one last time to the Parisian basin towards the end of the Paleogene period, leaving several layers of varied sediment capped with a thick layer of clay. This last deposit was important when the Paris basin rose from the sea, this time definitively, during the early Neogene, as the topmost layer would protect the soluble gypsum layers from erosion by air and weathering.

Erosion

Paris began to take the form we know at present as huge rivers resulting from the melting of successive ice ages cut through millions of years of sediment, leaving only formations too elevated or too resistant to erosion. Paris's hills of Montmartre and Belleville are the only places where gypsum remained, as the ancestor of the river Seine once flowed, almost along its present path, as wide as half the city, with many arms and tributaries.

Mining techniques

Open-air quarries

The most primitive mining technique was to extract a mineral where it could be seen on the surface, in places where millennia of erosion by the ancestors of the Paris basin's rivers Seine, Marne and Bièvre[4] exposed many levels of Paris's underlying stratification to open air. Minerals available from the surface, beginning with Paris's highest elevations in the valleys created by this erosion are: the plaster deposits in the upper reaches of the Right Bank hills of Montmartre and Belleville; lower in the valleys are sand and limestone deposits nearest the surface on Paris's Left Bank. The underlying clay strata were accessible from the surface in the lowest points of the Seine, Marne and Bièvre river valleys.

Underground mining

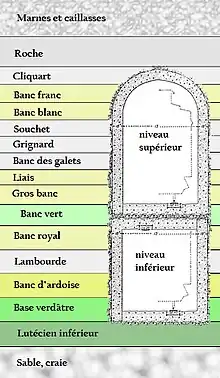

Open-air quarrying became quite difficult and even costly when the desired minerals lay below the surface, as sometimes enormous amounts of earth and other unwanted deposits would have to be removed before it could be extracted. One means of avoiding this problem was to dig horizontally into a hillside along the mineral strata from where it was visible in its flank, but the Paris area had few mineral deposits, save gypsum, the disposition of which fulfilled these conditions. There were few open-air stone quarries by the 15th century; instead, miners would access the targeted stone deposit through vertical wells, and dig into it horizontally from there. Although it seems that well-mining method only began then, there is evidence that Romans used this technique to mine clay under Paris's Left Bank Montagne Sainte-Geneviève hill.

Piliers tournés

No matter the means they used to access the underground mineral, miners had to provide a means of maintaining the enormous weight of the ceiling over their horizontally-burrowed excavations. The earliest means to this end, in a technique called piliers tournés, became common from the late 10th century. A tunnel would be dug horizontally along the deposit, tunnels perpendicular to the first were opened along the way, and tunnels parallel to the initial tunnel would be opened through these. The result was a grid of columns of untouched mineral deposit, or piliers tournés, that prevented a mine's collapse. In areas where a mineral was removed in a wider swath than the rest of the mine, usually towards the edge of the exploitation, miners would complement the natural mineral columns with piliers à bras, or stacks of stone creating a supporting column between floor and ceiling.

Gypsum mines, the origin of the famous plaster of Paris, used this technique with an added third dimension: as some of northern Paris's gypsum deposits measured 14 metres (46 ft) thick in some places, miners would create their tunnel grids in the top of the deposit, then begin extracting downwards. A gypsum mine in a particularly thick deposit had almost a cathedral-like air upon depletion, because of the towering columns and arches of mineral remaining. Only one example of this sort of gypsum-mining remains in Paris, in a renovated "grotto" under the Buttes-Chaumont gardens.

This method of burrowing was effective for the short-term, but over time the relatively soft mineral, subject to the elements and the earth's shifting, could erode or fissure, endangering the solidity of the mine.

Hagues et bourrages

Another technique appearing towards the early 18th century, hagues et bourrages, was both more economically and structurally sound. Instead of tunnelling into the exploitable mineral, miners would begin at a central point and extract stone progressively outwards; when they had mined to a point that left a wide area of the ceiling unsupported, they would erect a line of piliers à bras, continue their extraction beyond that line, then return to build a second parallel line of stone columns. The space along both lines of columns was then transformed into walls with stone blocks, or hagues, and the space between filled with packed rubble and other mineral detritus (or bourrage). This technique allowed much more of the targeted mineral to be extracted, and provided a support that could both settle and shift with the mine ceiling it supported.

Paris's growth over abandoned mine sites

There is no concrete proof of any mining activity before the late 13th century. The earliest known text is a brief mention in the town commerce register: Paris had 18 quarriers during 1292. The first written act concerning any mine dates from almost a century later, 1373, in an authorisation that a certain Dame Perrenelle be permitted to operate the plaster mine already existing in her property to the lower flank of Montmartre.

The majority of Paris's limestone deposits were in its Left Bank, and at the time of the city populace's 10th-century move to the Right Bank, were well in the suburbs of the former Roman/Merovingian city. As the stone from abandoned ruins became depleted during the 13th century, new mines began to open further from the city centre. Earlier mines closer to the city centre, when discovered, sometimes served a new purpose; when Louis XI donated the former Château Vauvert, a property which now forms the northern part of the Luxembourg Garden, to the Chartreuse order during 1259. The monks renovated the caverns under this property into wine cellars, and continued the exploitation of stone to the ancient mine's extremities.

By the early 16th century, there were stone excavations operating around the present Jardin des Plantes, Boulevard St-Marcel, Val-de-Grâce hospital, southern Luxembourg (by then the Chartreuse Coventry), and in areas around the rue Vaugirard. Paris's then suburban plaster mines remained for the most part in the Right Bank Montmartre and Belleville hills.

It was only with its expansion past its 13th-century walls (following almost exactly today's metro lines 6 and 2) that the city began to build on previously-mined land, which eventually resulted in many cave-ins and other disasters. The Left Bank faubourgs or suburbs were the most at risk: during the 15th century, the largest demographic expansions over mined land were the faubourg Saint-Victor (from the eastern extremity of the rue des Écoles and south down the rue Geoffroy St Hilaire); the faubourg St Marcel (rue Descartes, rue Mouffetard); the faubourg Saint-Jacques (along the present rue Saint-Jacques below the rue Soufflot), and the faubourg (then bourg) Saint-Germain-des-Prés to the south of the still-standing church of the same name.

Although the 17th-century Right Bank city of Paris had during five centuries expanded past three successive arcs of fortifications, Left Bank Paris was nowhere near as dense in comparison within its unchanged but crumbling 13th-century city walls. Many royal and ecclesiastical institutions came to the area during this period, but it seems that the mined state of the Paris faubourg underground had been forgotten by then. The Val de Grâce coventry and the Observatory, built from 1645 and 1672 respectively, were found to be undermined by immense caverns left by long-abandoned stone mines, reinforcing which consumed most of the budget reserved for both projects.

Growth of the faubourgs continued along the main routes from the city, but began to expand at a faster rate with the increase of traffic along the routes to the palaces of Fontainebleau and Versailles. The route de Fontainebleau (extending to the south of the present Place Denfert-Rochereau), then called Rue d'Enfer ("Hell Street") and now named Avenue Denfert-Rochereau, would be the site of one of Paris's first major mine collapses during December 1774,[5] when about 30 metres (100 ft) of the street collapsed to a depth of about thirty metres (one hundred feet).[6][7]

Abandoned mine consolidation

The 1774 disaster was partly responsible for the Royal Council's decision to create a special division of architects responsible for the inspection, maintenance, and repair of the ground under royal buildings within and around Paris. Another division of inspectors created about the same time, but directed by the Ministry of Finance, claimed the role of assuring the safety of the national roadways that were their jurisdiction. Created officially on 24 April 1777,[8] the Inspection générale des carrières (IGC)[9] entered service on the same eve after a new collapse of the route de Fontainebleau (Avenue Denfert-Rochereau) outside of the barrière d'Enfer ("barrier of hell") city gateway. Although the Ministry of Finance continued to claim jurisdiction of damaged roadways, this rather inept service was eventually succeeded by the Crown-appointed IGC.

As the centuries of mining under Paris's underground were mostly uncharted and thus largely forgotten, the real extent of former mines was unknown then. All important buildings and roadways were inspected, any signs of shifting were noted, and the ground underneath was sounded for cavities. Roadways were particularly problematic; instead of sounding the ground around the route, inspectors instead tunneled directly under the length of endangered roadway, filling any cavities they found along the way, and reinforcing the walls of their tunnels with solid masonry to eliminate the possibility of any future excavations and disasters. When a length of roadway was consolidated, the date of the work was engraved in the tunnel wall under it, next to the name of the roadway above; Paris's tunnel renovations, dating to as early as 1777, are now still a testimony to Paris's old street names and roadways.

Re-use of abandoned mines as a municipal ossuary

During the 18th century, the growing population of Paris resulted in the filling of existing cemeteries, causing public health concerns.[10] Towards the end of the 18th century, it was decided to create three new large cemeteries and to relocate the existing cemeteries within the city limits. Human remains were progressively moved to a renovated section of the abandoned mines that would eventually become a full-fledged ossuary whose entrance is located on present day Place Denfert-Rochereau.[11]

The ossuary became a tourist attraction on a small scale from the early 19th century, and has been open to the public on a regular basis from 1867. Although it is officially named the Ossuaire Municipal, it is known popularly as "the catacombs". Though the entire subterranean network of Paris's mines is not a burial place as such, the term "Catacombs of Paris" is also used commonly to refer to the whole.

References

- Hammel, Katie (22 September 2009). "Paris catacombs vandalized, closed for repair". Gadling. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- Association des sédimentologistes français (1998). Dynamics and Methods of Study of Sedimentary Basins. Editions TECHNIP. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-2-7108-0739-1.

- Donald R. Prothero (13 July 2006). After the Dinosaurs: The Age of Mammals. Indiana University Press. pp. 129–. ISBN 0-253-00055-6.

- International Association for the Advancement of Science, Arts, and Education (1900). Guide to Paris: the exhibition and the assembly. Paris International Assembly.

- Shea, Neil. "Under Paris". National Geographic. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- "Life Below The City Of Light: Paris Underground". NPR.org.

- "World Timeline of Facts #3 ~ 1750 - 1780".

- Elzas, Sara (2011-03-31). "The man who saved Paris from sinking". Radio France International. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- National Geographic Learning (15 October 2012). National Geographic Reader: Travel and Tourism. Cengage Learning. pp. 118–. ISBN 978-1-285-53155-7.

- "Urban legends and black masses: The eerie secrets of the Paris Catacombs". thejournal.ie. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- Michelin Travel & Lifestyle (1 April 2011). Michelin Green Guide Paris. Michelin Travel & Lifestyle. pp. 354–. ISBN 978-2-06-718220-2.

Further reading

- Gérards, Emile (1908). Paris Souterrain (in French). Sides. ISBN 2840220024.