San Jose, California

San Jose, officially the City of San José (Spanish for 'Saint Joseph'[11] /ˌsæn hoʊˈzeɪ, -ˈseɪ/ SAN hoh-ZAY, -SAY; Spanish: [saŋ xoˈse]),[12] is the largest city in Northern California by both population and area. With a 2020 population of 1,013,240,[13] it is the most populous city in both the Bay Area and the San Jose–San Francisco–Oakland Combined Statistical Area, which has a 2015 population of 7.7 million and 9.7 million people respectively,[14] the third-most populous city in California after Los Angeles and San Diego, and the 12th-most populous in the United States.[15][16] Located in the center of the Santa Clara Valley on the southern shore of San Francisco Bay, San Jose covers an area of 179.97 sq mi (466.1 km2). San Jose is the county seat of Santa Clara County and the main component of the San Jose–Sunnyvale–Santa Clara Metropolitan Statistical Area, with an estimated population of around two million residents in 2018.[17]

San Jose | |

|---|---|

| City of San José | |

Seal  | |

| Motto: Capital of Silicon Valley | |

| Coordinates: 37°20′10″N 121°53′26″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Santa Clara |

| Region | San Francisco Bay Area |

| Metro | San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara |

| CSA | San Jose-San Francisco-Oakland |

| Pueblo founded | November 29, 1777 |

| Founded as | Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe |

| Incorporated | March 27, 1850[1] |

| Named for | Saint Joseph |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager[2] |

| • Body | San Jose City Council |

| • Mayor | Matt Mahan[3] (D) |

| • Vice mayor | Rosemary Kamei (D) |

| • City Council | Sergio Jimenez (D) Omar Torres (D) David Cohen (D) Peter Ortiz (D) Dev Davis (I) Bien Doan (R) Domingo Candelas (D) Pam Foley (D) Arjun Batra (D) |

| • City Manager | Jennifer Maguire[4] |

| • Assemblymembers[5] | List |

| Area | |

| • City | 181.36 sq mi (469.72 km2) |

| • Land | 178.24 sq mi (461.63 km2) |

| • Water | 3.12 sq mi (8.09 km2) 1.91% |

| • Urban | 285.48 sq mi (739.4 km2) |

| • Metro | 2,694.61 sq mi (6,979 km2) |

| Elevation | 82 ft (25 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 1,013,240 |

| • Rank | 26th in North America 12th in the United States 3rd in California |

| • Density | 5,684.69/sq mi (2,194.92/km2) |

| • Urban | 1,837,446 (US: 28th) |

| • Urban density | 6,436.4/sq mi (2,485.1/km2) |

| • Metro | 2,000,468 (US: 35th) |

| Demonym(s) | San Josean(s) San Joséan(s) Josefino/a(s) |

| Time zone | UTC−08:00 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−07:00 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | List

|

| Area code(s) | 408/669 |

| FIPS code | 06-68000 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1654952, 2411790 |

| Website | www |

San Jose is notable for its innovation, cultural diversity,[18] affluence,[19] and sunny and mild Mediterranean climate.[20] Its connection to the booming high tech industry phenomenon known as Silicon Valley[21] prompted Mayor Tom McEnery to adopt the city motto of "Capital of Silicon Valley" in 1988 to promote the city.[22] Major global tech companies including Cisco Systems, eBay, Adobe Inc., PayPal, Broadcom, Samsung, Acer, and Zoom maintain their headquarters in San Jose. San Jose is one of the wealthiest major cities in the world, with the third-highest GDP per capita (after Zürich and Oslo)[23] and the fifth-most expensive housing market.[24] It is home to one of the world's largest overseas Vietnamese populations,[25] a Hispanic community that makes up over 40% of the city's residents,[26] and historic ethnic enclaves such as Japantown and Little Portugal.

Before the arrival of the Spanish, the area around San Jose was long inhabited by the Tamien nation of the Ohlone peoples of California. San Jose was founded on November 29, 1777, as the Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe, the first city founded in the Californias.[27] It became a part of Mexico in 1821 after the Mexican War of Independence.

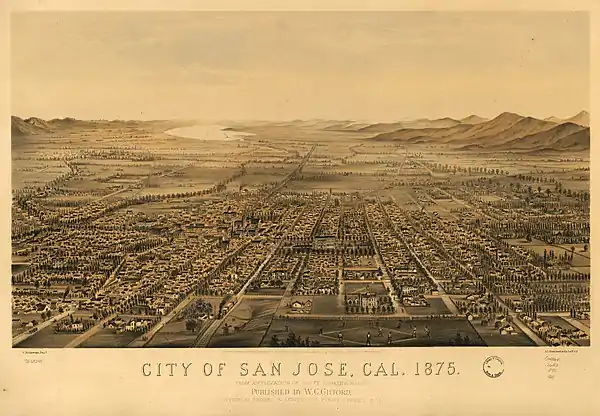

Following the American Conquest of California during the Mexican–American War, the territory was ceded to the United States in 1848. After California achieved statehood two years later, San Jose was designated as the state's first capital.[28] Following World War II, San Jose experienced an economic boom, with a rapid population growth and aggressive annexation of nearby cities and communities carried out in the 1950s and 1960s. The rapid growth of the high-technology and electronics industries further accelerated the transition from an agricultural center to an urbanized metropolitan area. Results of the 1990 U.S. census indicated that San Jose had officially surpassed San Francisco as the most populous city in Northern California.[29] By the 1990s, San Jose had become the global center for the high tech and internet industries, making it California's fastest-growing economy.[30]

Name

San Jose is named after el Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe (Spanish for 'the Town of Saint Joseph of Guadalupe'), the city's predecessor, which was eventually located in the area of what is now the Plaza de César Chávez. In the 19th century, print publications used the spelling "San José" for both the city and its eponymous township.[31][32] On December 11, 1943, the United States Board on Geographic Names ruled that the city's name should be spelled "San Jose" based on local usage and the formal incorporated name.[33]

In the 1960s and 1970s, some residents and officials advocated for returning to the original spelling of "San José", with the acute accent on the "e", to acknowledge the city's Mexican origin and Mexican-American population. On June 2, 1969, the city adopted a flag designed by historian Clyde Arbuckle that prominently featured the inscription "SAN JOSÉ, CALIFORNIA".[34] On June 16, 1970, San Jose State College officially adopted "San José" as the city's name, including in the college's own name.[35] On August 20, 1974, the San Jose City Council approved a proposal by Catherine Linquist to rename the city "San José"[36][37] but reversed itself a week later under pressure from residents concerned with the cost of changing typewriters, documents, and signs.[38] On April 3, 1979, the city council once again adopted "San José" as the spelling of the city name on the city seal, official stationery, office titles and department names.[39] As late as 2010, the 1965 city charter stated the name of the municipal corporation as City of San Jose, without the accent mark,[40][41] but later editions have added the accent mark.[11]

By convention, the spelling San José is only used when the name is spelled in mixed upper- and lowercase letters, but not when the name is spelled only in uppercase letters, as on the city logo. The accent reflects the Spanish version of the name, and the dropping of accents in all-capital writing was once typical in Spanish. While San José is commonly spelled both with and without the acute accent over the "e", the city's official guidelines indicate that it should be spelled with the accent most of the time and sets forth narrow exceptions, such as when the spelling is in URLs, when the name appears in all-capital letters, when the name is used on social media sites where the diacritical mark does not render properly, and where San Jose is part of the proper name of another organization or business, such as San Jose Chamber of Commerce, that has chosen not to use the accent-marked name.[42][43][44]

History

Pre-colonial period

San Jose, along with most of the Santa Clara Valley, has been home to the Tamien group (also spelled as Tamyen, Thamien) of the Ohlone people since around 4,000 BC.[45][46][47] The Tamien spoke Tamyen language of the Ohlone language family.

During the era of Spanish colonization and the subsequent building of Spanish missions in California, the Tamien people's lives changed dramatically. From 1777 onward, most of the Tamien people were forcibly enslaved at Mission Santa Clara de Asís or Mission San José where they were baptized and educated to be Catholic neophytes, also known as Mission Indians. This continued until the mission was secularized by the Mexican Government in 1833. A large majority of the Tamien died either from disease in the missions, or as a result of the state sponsored genocide. Some surviving families remained intact, migrating to Santa Cruz after their ancestral lands were granted to Spanish and Mexican Immigrants.[48]

Spanish period

California was claimed as part of the Spanish Empire in 1542, when explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo charted the Californian coast. During this time Alta California and the Baja California peninsula were administered together as Province of the Californias (Spanish: Provincia de las Californias). For nearly 200 years, the Californias remained a distant frontier region largely controlled by the numerous Native Nations and largely ignored by the government of the Viceroyalty of New Spain in Mexico City. Shifting power dynamics in North America—including the British/American victory and acquisition of North America, east of the Mississippi following the 1763 Treaty of Paris, as well as the start of Russian colonization of northwestern North America— prompted Spanish/Mexican authorities to sponsor the Portolá Expedition to survey Northern California in 1769.[49]

In 1776, the Californias were included as part of the Captaincy General of the Provincias Internas, a large administrative division created by José de Gálvez, Spanish Minister of the Indies, in order to provide greater autonomy for the Spanish Empire's borderlands. That year, King Carlos III of Spain approved an expedition by Juan Bautista de Anza to survey the San Francisco Bay Area, in order to choose the sites for two future settlements and their accompanying mission. De Anza initially chose the site for a military settlement in San Francisco, for the Royal Presidio of San Francisco, and Mission San Francisco de Asís. On his way back to Mexico from San Francisco, de Anza chose the sites in Santa Clara Valley for a civilian settlement, San Jose, on the eastern bank of the Guadalupe River, and a mission on its western bank, Mission Santa Clara de Asís.[50]

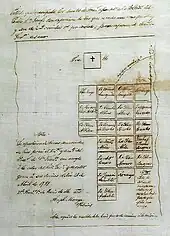

.jpg.webp)

San Jose was officially founded as California's first civilian settlement on November 29, 1777, as the Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe by José Joaquín Moraga, under orders of Antonio María de Bucareli y Ursúa, Viceroy of New Spain.[51] San Jose served as a strategic settlement along El Camino Real, connecting the military fortifications at the Monterey Presidio and the San Francisco Presidio, as well as the California mission network.[52] In 1791, due to the severe flooding which characterized the pueblo, San Jose's settlement was moved approximately a mile south, centered on the Pueblo Plaza (modern-day Plaza de César Chávez).[53]

In 1800, due to the growing population in the northern part of the Californias, Diego de Borica, Governor of the Californias, officially split the province into two parts: Alta California (Upper California), which would eventually become several western U.S. states, and Baja California (Lower California), which would eventually become two Mexican states.

Mexican period

San Jose became part of the First Mexican Empire in 1821, after Mexico's War of Independence was won against the Spanish Crown, and in 1824, part of the First Mexican Republic. With its newfound independence, and the triumph of the republican movement, Mexico set out to diminish the Catholic Church's power within Alta California by secularizing the California missions in 1833.

In 1824, in order to promote settlement and economic activity within sparsely populated California, the Mexican government began an initiative, for Mexican and foreign citizens alike, to settle unoccupied lands in California. Between 1833 and 1845, thirty-eight rancho land grants were issued in the Santa Clara Valley, 15 of which were located within modern-day San Jose's borders. Numerous prominent historical figures were among those granted rancho lands in the Santa Valley, including James A. Forbes, founder of Los Gatos, California (granted Rancho Potrero de Santa Clara), Antonio Suñol, Alcalde of San Jose (granted Rancho Los Coches), and José María Alviso, Alcalde of San Jose (granted Rancho Milpitas).

In 1835, San Jose's population of approximately 700 people included 40 foreigners, primarily Americans and Englishmen. By 1845, the population of the pueblo had increased to 900, primarily due to American immigration. Foreign settlement in San Jose and California was rapidly changing Californian society, bringing expanding economic opportunities and foreign culture.[54]

By 1846, native Californios had long expressed their concern for the overrunning of California society by its growing and wealthy Anglo-American community.[55] During the 1846 Bear Flag Revolt, Captain Thomas Fallon led nineteen volunteers from Santa Cruz to the pueblo of San Jose, which his forces easily captured. The raising of the flag of the California Republic ended Mexican rule in Alta California on July 14, 1846.[56][57]

American period

By the end of 1847, the Conquest of California by the United States was complete, as the Mexican–American War came to an end.[46] In 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo formally ceded California to the United States, as part of the Mexican Cession. On December 15, 1849, San Jose became the capital of the unorganized territory of California. With California's Admission to the Union on September 9, 1850, San Jose became the state's first capital.[58]

On March 27, 1850, San Jose was incorporated. It was incorporated on the same day as San Diego and Benicia; together, these three cities followed Sacramento as California's earliest incorporated cities.[59] Josiah Belden, who had settled in California in 1842 after traversing the California Trail as part of the Bartleson Party and later acquired a fortune, was the city's first mayor.[60] San Jose was briefly California's first state capital, and legislators met in the city from 1849 to 1851. (Monterey was the capital during the period of Spanish California and Mexican California).[61] The first capitol no longer exists; the Plaza de César Chávez now lies on the site, which has two historical markers indicating where California's state legislature first met.[62]

In the period 1900 through 1910, San Jose served as a center for pioneering invention, innovation, and impact in both lighter-than-air and heavier-than-air flight. These activities were led principally by John Montgomery and his peers. The City of San Jose has established Montgomery Park, a Monument at San Felipe and Yerba Buena Roads, and John J. Montgomery Elementary School in his honor. During this period, San Jose also became a center of innovation for the mechanization and industrialization of agricultural and food processing equipment.[63]

Though not affected as severely as San Francisco, San Jose also suffered significant damage from the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Over 100 people died at the Agnews Asylum (later Agnews State Hospital) after its walls and roof collapsed,[64] and San Jose High School's three-story stone-and-brick building was also destroyed. The period during World War II was tumultuous; Japanese Americans primarily from Japantown were sent to internment camps, including the future mayor Norman Mineta. Following the Los Angeles zoot suit riots, anti-Mexican violence took place during the summer of 1943. In 1940, the Census Bureau reported San Jose's population as 98% white.[65]

As World War II started, the city's economy shifted from agriculture (the Del Monte cannery was the largest employer and closed in 1999[66]) to industrial manufacturing with the contracting of the Food Machinery Corporation (later known as FMC Corporation) by the United States War Department to build 1,000 Landing Vehicle Tracked.[67] After World War II, FMC (later United Defense, and currently BAE Systems) continued as a defense contractor, with the San Jose facilities designing and manufacturing military platforms such as the M113 Armored Personnel Carrier, the Bradley Fighting Vehicle, and various subsystems of the M1 Abrams battle tank.[68]

IBM established its first West Coast operations in San Jose in 1943 with a downtown punch card plant, and opened an IBM Research lab in 1952. Reynold B. Johnson and his team developed direct access storage for computers,[69] inventing the RAMAC 305 and the hard disk drive; the technological side of San Jose's economy grew.[70]

During the 1950s and 1960s, City Manager A. P. "Dutch" Hamann led the city in a major growth campaign. The city annexed adjacent areas, such as Alviso and Cambrian Park, providing large areas for suburbs. An anti-growth reaction to the effects of rapid development emerged in the 1970s, championed by mayors Norman Mineta and Janet Gray Hayes. Despite establishing an urban growth boundary, development fees, and the incorporations of Campbell and Cupertino, development was not slowed, but rather directed into already-incorporated areas.[67]

San Jose's position in Silicon Valley triggered further economic and population growth. Results from the 1990 U.S. Census indicated that San Jose surpassed San Francisco as the most populous city in the Bay Area for the first time.[29] This growth led to the highest housing-cost increase in the nation, 936% between 1976 and 2001.[71] Efforts to increase density continued into the 1990s when an update of the 1974 urban plan kept the urban growth boundaries intact and voters rejected a ballot measure to ease development restrictions in the foothills. As of 2006, sixty percent of the housing built in San Jose since 1980 and over three-quarters of the housing built since 2000 have been multifamily structures, reflecting a political propensity toward Smart Growth planning principles.[72]

Geography

San Jose is located at 37°20′10″N 121°53′26″W. San Jose is located within the Santa Clara Valley, in the southern part of the Bay Area in Northern California. The northernmost portion of San Jose touches San Francisco Bay at Alviso, though most of the city lies away from the bayshore. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 180.0 sq mi (466 km2), making the fourth-largest city in California by land area (after Los Angeles, San Diego and California City).[15]

San Jose lies between the San Andreas Fault, the source of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, and the Calaveras Fault. San Jose is shaken by moderate earthquakes on average one or two times a year. These quakes originate just east of the city on the creeping section of the Calaveras Fault, which is a major source of earthquake activity in Northern California. On April 14, 1984, at 1:15 pm local time, a 6.2 magnitude earthquake struck the Calaveras Fault near San Jose's Mount Hamilton.[75] The most serious earthquake, in 1906, damaged many buildings in San Jose as described earlier. Earlier significant quakes rocked the city in 1839, 1851, 1858, 1864, 1865, 1868, and 1891. The Daly City Earthquake of 1957 caused some damage. The Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989 also did some damage to parts of the city.

Cityscape

San Jose's expansion was made by the design of "Dutch" Hamann, the City Manager from 1950 to 1969. During his administration, with his staff referred to as "Dutch's Panzer Division", the city annexed property 1,389 times,[76] growing the city from 17 to 149 sq mi (44 to 386 km2),[77] absorbing the communities named above, changing their status to "neighborhoods."

They say San José is going to become another Los Angeles. Believe me, I'm going to do everything in my power to make that come true.

— "Dutch" Hamann, 1965[78]

Sales taxes were a chief source of revenue. Hamann would determine where major shopping areas would be, and then annex narrow bands of land along major roadways leading to those locations, pushing tentacles across the Santa Clara Valley and, in turn, walling off the expansion of adjacent communities.[79]

During his reign, it was said the City Council would vote according to Hamann's nod. In 1963, the State of California imposed Local Agency Formation Commissions statewide, but largely to try to maintain order with San Jose's aggressive growth. Eventually the political forces against growth grew as local neighborhoods bonded together to elect their own candidates, ending Hamann's influence and leading to his resignation.[80] While the job was not complete, the trend was set. The city had defined its sphere of influence in all directions, sometimes chaotically leaving unincorporated pockets to be swallowed up by the behemoth, sometimes even at the objection of the residents.[76]

Major thoroughfares in the city include Monterey Road, the Stevens Creek Boulevard/San Carlos Street corridor, Santa Clara Street/Alum Rock Avenue corridor, Almaden Expressway, Capitol Expressway, and 1st Street (San Jose).

Topography

The Guadalupe River runs from the Santa Cruz Mountains flowing north through San Jose, ending in the San Francisco Bay at Alviso. Along the southern part of the river is the neighborhood of Almaden Valley, originally named for the mercury mines which produced mercury needed for gold extraction from quartz during the California Gold Rush as well as mercury fulminate blasting caps and detonators for the U.S. military from 1870 to 1945.[81] East of the Guadalupe River, Coyote Creek also flows to south San Francisco Bay and originates on Mount Sizer near Henry W. Coe State Park and the surrounding hills in the Diablo Range, northeast of Morgan Hill, California.

The lowest point in San Jose is 13 ft (4.0 m) below sea level at the San Francisco Bay in Alviso;[82] the highest is 2,125 ft (648 m).[83] Because of the proximity to Lick Observatory atop Mount Hamilton, San Jose has taken several steps to reduce light pollution, including replacing all street lamps and outdoor lighting in private developments with low pressure sodium lamps.[84] To recognize the city's efforts, the asteroid 6216 San Jose was named after the city.[85]

There are four distinct valleys in the city of San Jose: Almaden Valley, situated on the southwest fringe of the city; Evergreen Valley to the southeast, which is hilly all throughout its interior; Santa Clara Valley, which includes the flat, main urban expanse of the South Bay; and the rural Coyote Valley, to the city's extreme southern fringe.[86]

The extensive droughts in California, coupled with the drainage of the reservoir at Anderson Lake for seismic repairs, have strained the city's water security.[87][88] San Jose has suffered from lack of precipitation and water scarcity to the extent that some residents may run out of household water by the summer of 2022.[89]

Climate

San Jose, like most of the Bay Area, has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen Cs),[90] with warm to hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters. San Jose has an average of 298 days of sunshine and an annual mean temperature of 60.5 °F (15.8 °C). It lies inland, surrounded on three sides by mountains, and does not front the Pacific Ocean like San Francisco. As a result, the city is somewhat more sheltered from rain, giving it a semi-arid feel with a mean annual rainfall of 15.82 in or 401.8 mm, compared to some other parts of the Bay Area, which can receive about three times that amount.

Like most of the Bay Area, San Jose is made up of dozens of microclimates. Because of a more prominent rain shadow from the Santa Cruz Mountains, Downtown San Jose experiences the lightest rainfall in the city, while South San Jose, only 10 mi (16 km) distant, experiences more rainfall, and somewhat more extreme temperatures. San Jose barely avoids a temperate steppe (BSk) climate.

The monthly daily average temperature ranges from around 50 °F (10 °C) in December and January to around 70 °F (21.1 °C) in July and August.[91] The highest temperature ever recorded in San Jose was 112 °F (44 °C) on September 6, 2022; the lowest was 19 °F (−7.2 °C) on December 22–23, 1990. On average, there are 2.7 mornings annually where the temperature drops to, or below, the freezing mark; and sixteen afternoons where the high reaches or exceeds 90 °F or 32.2 °C. Diurnal temperature variation is far wider than along the coast or in San Francisco but still a shadow of what is seen in the Central Valley.

| Climate data for San Jose, California (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

81 (27) |

89 (32) |

95 (35) |

102 (39) |

107 (42) |

108 (42) |

105 (41) |

112 (44) |

101 (38) |

85 (29) |

79 (26) |

112 (44) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 68.2 (20.1) |

73.2 (22.9) |

79.1 (26.2) |

85.7 (29.8) |

89.8 (32.1) |

96.9 (36.1) |

95.0 (35.0) |

95.7 (35.4) |

95.7 (35.4) |

89.4 (31.9) |

77.5 (25.3) |

68.0 (20.0) |

99.8 (37.7) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 59.0 (15.0) |

62.8 (17.1) |

66.4 (19.1) |

70.0 (21.1) |

74.9 (23.8) |

80.1 (26.7) |

82.2 (27.9) |

82.7 (28.2) |

81.4 (27.4) |

74.6 (23.7) |

65.0 (18.3) |

58.8 (14.9) |

71.5 (21.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 51.1 (10.6) |

54.1 (12.3) |

57.0 (13.9) |

59.9 (15.5) |

64.1 (17.8) |

68.5 (20.3) |

70.6 (21.4) |

71.2 (21.8) |

69.8 (21.0) |

64.2 (17.9) |

56.1 (13.4) |

50.8 (10.4) |

61.4 (16.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 43.3 (6.3) |

45.4 (7.4) |

47.6 (8.7) |

49.8 (9.9) |

53.3 (11.8) |

57.0 (13.9) |

59.1 (15.1) |

59.8 (15.4) |

58.2 (14.6) |

53.8 (12.1) |

47.2 (8.4) |

42.8 (6.0) |

51.4 (10.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 32.6 (0.3) |

35.0 (1.7) |

38.1 (3.4) |

41.3 (5.2) |

46.1 (7.8) |

50.1 (10.1) |

53.8 (12.1) |

53.9 (12.2) |

50.8 (10.4) |

45.5 (7.5) |

36.8 (2.7) |

32.2 (0.1) |

30.7 (−0.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 18 (−8) |

24 (−4) |

25 (−4) |

26 (−3) |

32 (0) |

33 (1) |

40 (4) |

39 (4) |

35 (2) |

30 (−1) |

21 (−6) |

19 (−7) |

18 (−8) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 2.97 (75) |

3.24 (82) |

2.64 (67) |

1.24 (31) |

0.54 (14) |

0.17 (4.3) |

0.01 (0.25) |

0.03 (0.76) |

0.07 (1.8) |

0.80 (20) |

1.36 (35) |

3.07 (78) |

16.14 (410) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.2 | 11.5 | 9.3 | 6.4 | 4.0 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 6.9 | 10.7 | 64.4 |

| Source: NOAA[92][93] | |||||||||||||

"Rain year" precipitation has ranged from 4.83 in (122.7 mm) between July 1876 and June 1877 to 30.30 in (769.6 mm) between July 1889 and June 1890, although at the current site since 1893 the range is from 5.33 in (135.4 mm) in "rain year" 2020–21 to 30.25 in (768.3 mm) in "rain year" 1982–83. 2020-2021 was the lowest precipitation year ever, in 127 years of precipitation records in San Jose. The most precipitation in one month was 12.38 in (314.5 mm) in January 1911. The maximum 24-hour rainfall was 3.60 in (91.4 mm) on January 30, 1968. On August 16, 2020, one of the most widespread and strong thunderstorm events in recent Bay Area history occurred as an unstable humid air mass moved up from the south and triggered multiple dry thunderstorms [94] which caused many fires to be ignited by 300+ lightning strikes in the surrounding hills. The CZU lightning complex fires took almost 5 months to fully be controlled. Over 86,000 acres were burned and nearly 1500 buildings were destroyed.[95][96]

The snow level drops as low as 4,000 ft (1,220 m) above sea level, or lower, occasionally coating nearby Mount Hamilton and, less frequently, the Santa Cruz Mountains, with snow that normally lasts a few days. Snow will snarl traffic traveling on State Route 17 towards Santa Cruz. Snow rarely falls in San Jose; the most recent snow to remain on the ground was on February 5, 1976, when many residents around the city saw as much as 3 in (0.076 m) on car and roof tops. The official observation station measured only 0.5 in (0.013 m) of snow.[97]

Neighborhoods and districts

The city is generally divided into the following areas: Central San Jose (centered on Downtown San Jose), West San Jose, North San Jose, East San Jose, and South San Jose. Many of San Jose's districts and neighborhoods were previously unincorporated communities or separate municipalities that were later annexed by the city.

Besides those mentioned above, some well-known communities within San Jose include Japantown, Rose Garden, Midtown San Jose, Willow Glen, Naglee Park, Burbank, Winchester, Alviso, East Foothills, Alum Rock, Communications Hill, Little Portugal, Blossom Valley, Cambrian, Almaden Valley, Little Saigon, Silver Creek Valley, Evergreen Valley, Mayfair, Edenvale, Santa Teresa, Seven Trees, Coyote Valley, and Berryessa. A distinct ethnic enclave in San Jose is the Washington-Guadalupe neighborhood, immediately south of the SoFA District; this neighborhood is home to a community of Hispanics, centered on Willow Street.

- Selection of neighborhoods in San Jose

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpeg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_(cropped2).jpg.webp)

Parks

San Jose possesses about 15,950 acres (6,455 ha) of parkland in its city limits, including a part of the expansive Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge. The city's oldest park is Alum Rock Park, established in 1872.[98] In its 2013 ParkScore ranking, The Trust for Public Land, a national land conservation organization, reported that San Jose was tied with Albuquerque and Omaha for having the 11th best park system among the 50 most populous U.S. cities.[99]

- Almaden Quicksilver County Park, 4,147 acres (16.78 km2) of former mercury mines in South San Jose (operated and maintained by the Santa Clara County Parks and Recreation Department).

- Alum Rock Park, 718 acres (2.91 km2) in East San Jose, the oldest municipal park in California and one of the largest municipal parks in the United States.

- Children's Discovery Museum hosts an outdoor park-like setting, featuring the world's largest permanent Monopoly game, per the Guinness Book of World Records.[100] Caretakers for this attraction include the 501(c)3 non-profit group Monopoly in the Park.

- Circle of Palms Plaza, a ring of palm trees surrounding a California state seal and historical landmark at the site of the first state capitol

- Emma Prusch Farm Park, 43.5 acres (17.6 ha) in East San Jose. Donated by Emma Prusch to demonstrate the valley's agricultural past, it includes a 4-H barn (the largest in San Jose), community gardens, a rare-fruit orchard, demonstration gardens, picnic areas, and expanses of lawn.[101]

- Field Sports Park, Santa Clara County's only publicly owned firing range, located in south San Jose[102]

- Iris Chang Park, located in North San Jose, is dedicated to the memory of Iris Shun-Ru Chang, author of The Rape of Nanking and a San Jose resident.

- Kelley Park, including diverse facilities such as Happy Hollow Park & Zoo (a child-centric amusement park), the Japanese Friendship Garden (Kelley Park), History Park at Kelley Park, and the Portuguese Historical Museum within the history park

- Martial Cottle Park, a former agricultural farm, in South San Jose. Operated by Santa Clara County Parks and Recreation Department

- Oak Hill Memorial Park, California's oldest secular cemetery

- Overfelt Gardens, including the Chinese Cultural Garden

- Plaza de César Chávez, a small park in Downtown, hosts outdoor concerts and the Christmas in the Park display

- Raging Waters, water park with water slides and other water attractions. This sits within Lake Cunningham Park

- Rosicrucian Park, nearly an entire city block in the Rose Garden neighborhood; the Park offers a setting of Egyptian and Moorish architecture set among lawns, rose gardens, statuary, and fountains, and includes the Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum, Planetarium, Research Library, Peace Garden and Visitors Center

- San Jose Municipal Rose Garden, 5+1⁄2 acres (22,000 m2) park in the Rose Garden neighborhood, featuring over 4,000 rose bushes

Trails

A 2011 study by Walk Score ranked San Jose the nineteenth most walkable of 50 largest cities in the United States.[103]

San Jose's trail network of 60 mi (100 km) of recreational and active transportation trails throughout the city.[104] The major trails in the network include:

- Coyote Creek Trail

- Guadalupe River Trail

- Los Gatos Creek Trail

- Los Alamitos Creek Trail

- Penitencia Creek Trail

- Silver Creek Valley Trail

This large urban trail network, recognized by Prevention Magazine as the nation's largest, is linked to trails in surrounding jurisdictions and many rural trails in surrounding open space and foothills. Several trail systems within the network are designated as part of the National Recreation Trail, as well as regional trails such as the San Francisco Bay Trail and Bay Area Ridge Trail.

Wildlife

Early written documents record the local presence of migrating salmon in the Rio Guadalupe dating as far back as the 18th century.[105] Both steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and King salmon are extant in the Guadalupe River, making San Jose the southernmost major U. S. city with known salmon spawning runs, the other cities being Anchorage, Alaska; Seattle, Washington; Portland, Oregon and Sacramento, California.[106] Runs of up to 1,000 Chinook or King Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) swam up the Guadalupe River each fall in the 1990s, but have all but vanished in the current decade apparently blocked from access to breeding grounds by impassable culverts, weirs and wide, exposed and flat concrete paved channels installed by the Santa Clara Valley Water District.[107] In 2011 a small number of Chinook salmon were filmed spawning under the Julian Street bridge.[108]

Conservationist Roger Castillo, who discovered the remains of a mammoth on the banks of the Guadalupe River in 2005, found that a herd of tule elk (Cervus canadensis) had recolonized the hills of south San Jose east of Highway 101 in early 2019.[109]

At the southern edge of San José, Coyote Valley is a corridor for wildlife migration between the Santa Cruz Mountains and the Diablo Range.[110][111]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 9,089 | — | |

| 1880 | 12,567 | 38.3% | |

| 1890 | 18,060 | 43.7% | |

| 1900 | 21,500 | 19.0% | |

| 1910 | 28,946 | 34.6% | |

| 1920 | 39,642 | 37.0% | |

| 1930 | 57,651 | 45.4% | |

| 1940 | 68,457 | 18.7% | |

| 1950 | 95,280 | 39.2% | |

| 1960 | 204,196 | 114.3% | |

| 1970 | 459,913 | 125.2% | |

| 1980 | 629,400 | 36.9% | |

| 1990 | 782,248 | 24.3% | |

| 2000 | 894,943 | 14.4% | |

| 2010 | 945,942 | 5.7% | |

| 2020 | 1,013,240 | 7.1% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 959,256 | [112] | −5.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[113] 2010–2020[13] | |||

In 2014, the US Census Bureau released its new population estimates. With a total population of 1,015,785,[114] San Jose became the 11th US city to reach one million residents. It is currently the largest US city with an Asian plurality population.

| Racial and ethnic composition | 2020 [13] | 2010[115] | 1990[65] | 1970[65] | 1940[65] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | 37.2% | 31.7% | 19.5% | 2.7% | 1.1% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 31.0% | 33.2% | 26.6% | 19.1% | n/a |

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 25.1% | 28.7% | 49.6% | 75.7% | 98.5% |

| Mixed | 7.9% | 2.7% | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Black or African American | 2.9% | 2.9% | 4.7% | 2.5% | 0.4% |

2010

The 2010 United States Census[116] reported that San Jose had a population of 945,942. The population density was 5,256.2 inhabitants per square mile (2,029.4/km2). The racial makeup of San Jose was 404,437 (42.8%) White, 303,138 (32.0%) Asian (10.4% Vietnamese, 6.7% Chinese, 5.6% Filipino, 4.6% Indian, 1.2% Korean, 1.2% Japanese, 0.3% Cambodian, 0.2% Thai, 0.2% Pakistani, 0.2% Laotian), 30,242 (3.2%) African American, 8,297 (0.9%) Native American, 4,017 (0.4%) Pacific Islander, 148,749 (15.7%) from other races, and 47,062 (5.0%) from two or more races. There were 313,636 residents of Hispanic or Latino background (33.2%). 28.2% of the city's population was of Mexican descent; the next largest Hispanic groups were those of Salvadoran (0.7%) and Puerto Rican (0.5%) heritage. Non-Hispanic Whites were 28.7% of the population in 2010,[115] down from 75.7% in 1970.[65]

The census reported that 932,620 people (98.6% of the population) lived in households, 9,542 (1.0%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 3,780 (0.4%) were institutionalized. There were 301,366 households, out of which 122,958 (40.8%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 162,819 (54.0%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 37,988 (12.6%) had a female householder with no husband present, 18,702 (6.2%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 16,900 (5.6%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 2,458 (0.8%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 59,385 households (19.7%) were made up of individuals, and 18,305 (6.1%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.09. There were 219,509 families (72.8% of all households); the average family size was 3.54.

The age distribution of the city was as follows: 234,678 people (24.8%) were under the age of 18, 89,457 people (9.5%) aged 18 to 24, 294,399 people (31.1%) aged 25 to 44, 232,166 people (24.5%) aged 45 to 64, and 95,242 people (10.1%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35.2 years. For every 100 females, there were 101.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 99.8 males.

There were 314,038 housing units at an average density of 1,745.0 per square mile (673.7/km2), of which 176,216 (58.5%) were owner-occupied, and 125,150 (41.5%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.6%; the rental vacancy rate was 4.3%. 553,436 people (58.5% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 379,184 people (40.1%) lived in rental housing units.

2000

According to the 2000 United States Census, there were 894,943 people, 276,598 households, and 203,576 families residing in the city.[117]

The population density was 5,117.9 inhabitants per square mile (1,976.0/km2). There were 281,841 housing units at an average density of 1,611.8 per square mile (622.3/km2). Of the 276,598 households, 38.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 56.0% were married couples living together, 11.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.4% were non-families. 18.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 4.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.20 and the average family size was 3.62.

In the city, the age distribution of the population shows 26.4% under the age of 18, 9.9% from 18 to 24, 35.4% from 25 to 44, 20.0% from 45 to 64, and 8.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 103.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 102.5 males.

According to a 2007 estimate, the median income for a household in the city was the highest in the U.S. for any city with more than a quarter-million residents with $76,963 annually. The median income for a family was $86,822.[118] Males had a median income of $49,347 versus $36,936 for females. The per capita income for the city was $26,697. About 6.0% of families and 8.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 10.3% of those under age 18 and 7.4% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

.jpg.webp)

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The CSA San Jose shares with San Francisco was the country's third-largest urban economy as of 2018, with a GDP of $1.03 trillion.[119] Of the 500+ primary statistical areas in the U.S., this CSA had among the highest GDP per capita in 2018, at $106,757.[119]

San Jose is a United States Foreign-Trade Zone. The city received its Foreign Trade Zone grant from the U.S. Federal Government in 1974, making it the 18th foreign-trade zone established in the United States. Under its grant, the City of San Jose is granted jurisdiction to oversee and administer foreign trade in Santa Clara County, Monterey County, San Benito County, Santa Cruz County, and in the southern parts of San Mateo County and Alameda County.[120]

San Jose hosts many companies with more than 1,000 employees, including the headquarters of:

San Jose also hosts major facilities for Becton Dickinson, Ericsson, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Hitachi, IBM, Kaiser Permanente, KLA Tencor, Lockheed Martin, Nippon Sheet Glass, and Qualcomm. The North American headquarters of Samsung Semiconductor are located in San Jose.[121][122] Approximately 2000 employees will work at the new Samsung campus which opened in 2015.

Other large companies based in San Jose include:

- Align Technology

- Atmel

- Bloom Energy

- CEVA

- Cypress Semiconductor

- Cohesity, Echelon

- Extreme Networks

- GlobalLogic

- Harmonic

- Integrated Device Technology

- Maxim Integrated

- Micrel

- Move

- Netgear

- Novellus Systems

- Nutanix

- Oclaro

- OCZ

- Quantum

- SunPower

- Sharks Sports and Entertainment

- Supermicro

- Tessera Technologies

- TiVo

- Ultratech

- VeriFone

- Viavi Solutions

- Zoom Video Communications

- Zscaler

Sizable government employers include the city government, Santa Clara County, and San Jose State University.[123] Acer's United States division has its offices in San Jose.[124] Prior to its closing, Netcom had its headquarters in San Jose.[125][126]

On July 31, 2015, Cupertino-based Apple Inc. purchased a 40-acre site in San Jose.[127] The site, which is bare land, will be the site of an office and research campus where it is estimated that up to 16,000 employees will be located. Apple paid $138.2 million for the site.[127] The seller, Connecticut-based Five Mile Capital Partners, paid $40 million for the site in 2010.[128]

Wealth

The San Jose Metropolitan Area has the most millionaires and billionaires in the United States per capita.[129] It is situated in the most affluent county in California and one of the most affluent counties in the United States.[130][131][132][133]

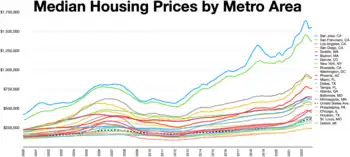

With a median home price of $1,085,000[134] and the highest percentage of million-dollar (or more) homes in the United States,[135] San Jose has the most expensive housing market in the United States and the fifth most expensive housing market in the world.[136][137][138]

The cost of living in San Jose and the surrounding areas is among the highest in California and the nation, according to 2004 data.[139] Housing costs are the primary reason for the high cost of living, although the costs in all areas tracked by the ACCRA Cost of Living Index are above the national average. Households in the city limits have the highest disposable income of any city in the U.S. with over 500,000 residents.[140][141]

Silicon Valley

The large concentration of high-technology engineering, computer, and microprocessor companies around San Jose has led the area to be known as Silicon Valley. Area schools such as the University of California, Berkeley, University of California, Santa Cruz, San Jose State University, San Francisco State University, California State University, East Bay, Santa Clara University, and Stanford University pump thousands of engineering and computer science graduates into the local economy every year.

San Jose residents produce more U.S. patents than any other city.[142] On October 15, 2015, the United States Patent and Trademark Office opened a satellite office in San Jose to serve Silicon Valley and the Western United States.[143][144] By April 2018, Google was in the process of planning the "biggest tech campus in Silicon Valley" in San Jose.[145] However, in April 2023, it was reported that Google paused on Google West San Jose Campus constructions due to slowing economic conditions and a decreased requirement for physical office space by tech companies,[146] although the tech ecosystem has also recently become more geographically dispersed.[147]

High economic growth during the tech bubble caused employment, housing prices, and traffic congestion to peak in the late 1990s. As the economy slowed in the early 2000s, employment and traffic congestion was somewhat diminished.[148] In the mid-2000s, traffic along major highways again began to worsen as the economy improved. San Jose had 405,000 jobs within its city limits in 2006, and an unemployment rate of 4.6%. San Jose has the highest median income of any U.S. city with over 280,000 people.

On March 14, 2013, San Jose implemented a public wireless connection in its downtown area. Wireless access points have been placed on outdoor light posts throughout the city.[149]

Media

San Jose is served by Greater Bay Area media. Print media outlets in San Jose include The Mercury News, the weekly Metro Silicon Valley, El Observador and the Silicon Valley / San Jose Business Journal. The Bay Area's NBC O&O, KNTV 11, is licensed to San Jose. In total, broadcasters in the Bay Area include 34 television stations, 25 AM radio stations, and 55 FM radio stations.[150]

In April 1909, Charles David Herrold, an electronics instructor in San Jose, constructed a radio station to broadcast the human voice. The station, "San Jose Calling" (call letters FN, later FQW), was the world's first radio station with scheduled programming targeted at a general audience. The station became the first to broadcast music in 1910. Herrold's wife Sybil became the first female "disk jockey" in 1912. The station changed hands a number of times before becoming today's KCBS in San Francisco.[151]

Top employers

As of June 30, 2021, the top employers in the city were:[152]

| No. | San Jose's Top Employers | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | County of Santa Clara | 18,700 |

| 2 | City of San Jose | 7,627 |

| 3 | Cisco Systems | 7,500 |

| 4 | PayPal | 3,868 |

| 5 | San Jose State University | 3,650 |

| 6 | Adobe Systems, Inc. | 3,400 |

| 7 | Kaiser Permanente | 3,035 |

| 8 | eBay | 2,800 |

| 9 | Western Digital | 2,759 |

| 10 | San Jose Unified School District | 2,679 |

| 11 | Target Stores | 2,437 |

| 12 | Super Micro Computer, Inc. | 2,230 |

| 13 | IBM | 2,200 |

| 14 | Cadence Design Systems | 1,956 |

| 15 | Good Samaritan Hospital | 1,850 |

Culture

Architecture

Because the downtown area is in the flight path to nearby Mineta San Jose International Airport (also evidenced in the above panoramic), there is a height limit for buildings in the downtown area, which is underneath the final approach corridor to the airport. The height limit is dictated by local ordinances, driven by the distance from the runway and a slope defined by Federal Aviation Administration regulations. Core downtown buildings are limited to approximately 300 ft (91 m) but can get taller farther from the airport.[153]

There has been broad criticism over the past few decades of the city's architecture.[154] Citizens have complained that San Jose is lacking in aesthetically pleasing architectural styles. Blame for this lack of architectural "beauty" can be assigned to the re-development of the downtown area from the 1950s onward, in which whole blocks of historic commercial and residential structures were demolished.[155] Exceptions to this include the Downtown Historic District, the Hotel De Anza, and the Hotel Sainte Claire, both of which are listed in the National Register of Historic Places for their architectural and historical significance.

.jpg.webp)

Municipal building projects have experimented more with architectural styles than have most private enterprises.[156] The Children's Discovery Museum, Tech Museum of Innovation, and the San Jose Repertory Theater building have experimented with bold colors and unusual exteriors. The new City Hall, designed by Richard Meier & Partners, opened in 2005 and is a notable addition to the growing collection of municipal building projects.[157]

San Jose has many examples of houses with fine architecture. Late 19th century and early 20th century styles exist in neighborhoods such as Hanchett Park, Naglee Park, Rose Garden, and Willow Glen (including Palm Haven).

Styles include Mediterranean Revival architecture, Spanish Colonial architecture, Neoclassical architecture, Craftsman, Mission Revival, Prairie style, and Queen Anne style Victorian.

Notable architects include Frank Delos Wolfe, Theodore Lenzen, Charles McKenzie,[158] and Julia Morgan.[159]

Visual arts

.jpg.webp)

Public art is an evolving attraction in the city. The city was one of the first to adopt a public art ordinance at 2% of capital improvement building project budgets,[160] and as a result of this commitment, a considerable number of public art projects exist in the downtown area, and a growing collection in neighborhoods including libraries, parks, and fire stations. In particular, the Mineta Airport expansion incorporated art and technology into its development. Early public art included a statue of Quetzalcoatl (the plumed serpent) downtown, controversial in its planning because some called it pagan, and controversial in its implementation because many felt that the final statue by Robert Graham did not look like a winged serpent, and was more noted for its expense than its aesthetics. Locals joked that the statue resembles a pile of feces.[161]

A statue of Thomas Fallon also met strong resistance from those who called him largely responsible for the decimation of early native populations. Chicano/Latino activists protested because he had captured San Jose by military force in the Mexican–American War (1846). They also protested the perceived "repression" of historic documents detailing Fallon's orders expelling many of the city's Californio (early Spanish/Mexican/Mestizo) residents. In October 1991 protests at Columbus Day and Dia de la Raza celebrations stalled than plan, and the statue was stored in a warehouse in Oakland for more than a decade. The statue returned in 2002 to a less conspicuous location: Pellier Park, a small triangular patch at the merge of West Julian and West St. James streets.[162]

In 2001, the city-sponsored SharkByte, an exhibit of decorated sharks based on the mascot of the hockey team, the San Jose Sharks, and modeled after Chicago's display of decorated cows.[163] Large models of sharks decorated in clever, colorful, or creative ways by local artists were displayed for months at dozens of locations around the city. After the exhibition, the sharks were auctioned off for charity.

In 2006, Adobe Systems commissioned an art installation titled San Jose Semaphore by Ben Rubin,[164] at the top of its headquarters building. Semaphore is composed of four LED discs which "rotate" to transmit a message. The content remained a mystery until it was deciphered in August 2007.[165][166] The visual art installation is supplemented with an audio track, transmitted from the building on a low-power AM station. The audio track provides clues to decode the message being transmitted.

San Jose retains a number of murals in the Chicano history tradition of Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco of murals as public textbooks.[167]

Although intended to be permanent monuments to the city's heritage as a mission town founded in 1777, a number of murals have been painted over, notably Mural de la Raza, on the side of a Story Rd shoe store, and Mexicatlan at the corner of Sunset and Alum Rock. In addition, two of three murals by Mexican artist Gustavo Bernal Navarro have disappeared.[167] The third mural, La Medicina y la Comunidad at the Gardner clinic on East Virginia Street, depicts both modern and traditional healers.[167]

Surviving Chicano history murals include Nuestra Senora de Guadelupe at Our Lady of Guadalupe church and the 1970s or 1980s Virgen de Guadelupe Huelga Bird at Cal Foods east of downtown. The Guadalajara restaurant has the 1986 Guadalajara Market No. 2 by Edward Earl Tarver III and a 2013 work by Jesus Rodriguez and Empire 7, La Gran Culture Resonance.[167]

An unknown artist painted the Huelga Bird and Aztec City mural in the 1970s or 1980s on the Clyde L. Fisher Middle School. In 1995 Antonio Nava Torres painted The Aztec Calendar Handball Court at Biebrach Park, and the unknown artist of Chaco's Pachuco painted it on the former Chaco's Restaurant in the 1990s. The Jerry Hernandez mural by Frank Torres at Pop's Mini Mart on King Road dates to 2009, and another recent mural by Carlos Rodriguez on the Sidhu Market at Locust and West Virginia depicts a stern-looking warrior.[167]

Performing arts

The city is home to many performing arts companies, including Opera San Jose, Symphony Silicon Valley, Ballet San Jose Silicon Valley, sjDANCEco, The San Jose Symphonic Choir, Children's Musical Theater of San Jose,[168] the San Jose Youth Symphony, the San Jose Repertory Theatre, City Lights Theatre Company, The Tabard Theatre Company, San Jose Stage Company, and the now-defunct American Musical Theatre of San Jose which was replaced by Broadway San Jose in partnership with Team San Jose. San Jose is also home to the San Jose Museum of Art,[169] one of the nation's premiere Modern Art museums.

The SAP Center at San Jose is one of the most active venues for events in the world. According to Billboard Magazine and Pollstar, the arena sold the most tickets to non-sporting events of any venue in the United States, and third in the world after the Manchester Evening News Arena in Manchester, England, and the Bell Centre in Montreal, Canada, for the period from January 1 – September 30, 2004.[170]

The annual Cinequest Film Festival in downtown has grown to over 60,000 attendees per year, becoming an important festival for independent films. The San Francisco Asian American Film Festival is an annual event, which is hosted in San Francisco, Berkeley, and Downtown San Jose. Approximately 30 to 40 films are screened in San Jose each year at the Camera 12 Downtown Cinemas. The San Jose Jazz Festival is another of many events hosted throughout the year.

The Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies houses the largest collection of Ludwig van Beethoven in the world, outside of Europe, and is the only institution of its kind in North America.

Sports

| Club | Sport | Founded | League | Venue (capacity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Jose Sharks | Hockey | 1991 | National Hockey League | SAP Center (17,562) |

| San Jose Earthquakes | Soccer | 1995 | Major League Soccer | PayPal Park (18,000) |

| San Jose Barracuda | Hockey | 2015 | American Hockey League (AAA) | Tech CU Arena (4,200) |

| San Jose Giants | Baseball | 1988 | California League (low-A) | Excite Ballpark (4,200) |

| San Jose State Spartans | NCAA Football | 1893 | Mountain West Conference | CEFCU Stadium (21,520) |

San Jose is home to the San Jose Sharks of the NHL, the San Jose Barracuda of the AHL, and the San Jose Earthquakes of Major League Soccer. The Sharks and the Barracuda play in the SAP Center at San Jose. The Earthquakes built an 18,000 seat new stadium that opened in March 2015. San Jose was a founding member of both the California League and Pacific Coast League in minor league baseball. San Jose currently fields the San Jose Giants, a Low-A affiliate of the San Francisco Giants.

San Jose has "aggressively wooed" the Oakland Athletics to relocate to San Jose from nearby Oakland, and the Athletics in turn have said that San Jose is their "best option", but the San Francisco Giants have thus far exercised a veto against this proposal.[171] In 2013, the city of San Jose sued Major League Baseball for not allowing the Athletics to relocate to San Jose.[172] On October 5, 2015, the United States Supreme Court rejected San Jose's bid on the Athletics.[173]

From 2005 to 2007, the San Jose Grand Prix, an annual street circuit race in the Champ Car World Series, was held in the downtown area. Other races included the Trans-Am Series, the Toyota Atlantic Championship, the United States Touring Car Championship, the Historic Stock Car Racing Series, and the Formula D Drift racing competition.

San Jose has been host to several U.S. Olympic team trials over the years. In 2004, the San Jose Sports Authority held the trials for judo, taekwondo, trampolining and rhythmic gymnastics at the San Jose State Event Center. SAP Center hosted the Gymnastic trials in 2012[174] and 2016 (women's only).[175] and the U.S. Figure Skating Championships (used in Olympic years to select the Olympians) in 1996, 2012, and 2018. It was due to host the 2021 Championship, but that was moved to Las Vegas and it will instead host 2023.[176] In 2008, around 90 percent of the members of the United States Olympic team were processed at San Jose State University prior to traveling to the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.[177] The 2009 Junior Olympics for trampoline were also held here.

In August 2004, the San Jose Seahawk Rugby Football Club hosted the USA All-Star Rugby Sevens Championships at Watson Bowl, east of Downtown. San Jose State hosted the 2011 American Collegiate Hockey Association (ACHA) national tournament.[178] The NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament is also frequently held in San Jose.

Landmarks

Notable landmarks in San Jose include Children's Discovery Museum of San Jose, History Park at Kelley Park, Cathedral Basilica of St. Joseph, Plaza de César Chávez, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library, Mexican Heritage Plaza, Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum, Lick Observatory, Hayes Mansion, SAP Center at San Jose, Hotel De Anza, San Jose Improv, Sikh Gurdwara of San Jose, Peralta Adobe, Excite Ballpark, Spartan Stadium, Japantown San Jose, Winchester Mystery House, Raging Waters, Circle of Palms Plaza, San Jose City Hall, San Jose Flea Market, Oak Hill Memorial Park, San Jose electric light tower, and The Tech Museum of Innovation.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The historic Sainte Claire Hotel, today The Westin San Jose

The historic Sainte Claire Hotel, today The Westin San Jose.jpg.webp)

Museums and institutions

- The Tech Museum of Innovation

- Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, which houses the largest collection of Ludwig van Beethoven in the world outside of Europe

- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library, the largest U.S. public library west of the Mississippi River

- San Jose Museum of Art, contemporary art museum with a collection of West Coast artists

- Children's Discovery Museum of San Jose

- History Park at Kelley Park

- Mexican Heritage Plaza, a Chicano museum and cultural center

- Movimiento de Arte y Cultura Latino Americana, is an inclusive contemporary arts museum grounded in the Chicano/Latino experience

- Portuguese Historical Museum

- Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum, the largest collection of Egyptian artifacts on display in the western United States, located at Rosicrucian Park

- San Jose East Carnegie Branch Library is notable as it is the last Carnegie library still operating in San Jose, and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

- San Jose Steam Railroad Museum, proposed, artifacts and rolling stock are kept at the fairgrounds and Kelley Park

- History San José

- Japanese American Museum of San Jose, a museum of Japanese-American history

- Old Bank of America Building a historic landmark

- San Jose Museum of Quilts & Textiles, the first museum in America dedicated solely to quilts and textiles as an art form

- Viet Museum, a museum of Vietnamese-American history

Law and government

Local

San Jose is a charter city under California law, giving it the power to enact local ordinances that may conflict with state law, within the limits provided by the charter.[179] The city has a council-manager government with a city manager nominated by the mayor and elected by the city council.

The San Jose City Council is made up of ten council members elected by district, and a mayor elected by the entire city. During city council meetings, the mayor presides, and all eleven members can vote on any issue. The mayor has no veto powers. Council members and the mayor are elected to four-year terms; the even-numbered district council members beginning in 1994; the mayor and the odd-numbered district council members beginning in 1996.[180] Each council member represents approximately 100,000 constituents.

Council members and the mayor are limited to two successive terms in office, although a council member that has reached the term limit can be elected mayor, and vice versa. The council elects a vice-mayor from the members of the council at the second meeting of the year following a council election. This council member acts as mayor during the temporary absence of the mayor, but does not succeed to the mayor's office upon a vacancy.[180]

.jpg.webp)

The City Manager is the chief administrative officer of the city, and must present an annual budget for approval by the city council. When the office is vacant, the Mayor proposes a candidate for City Manager, subject to council approval. The council appoints the Manager for an indefinite term, and may at any time remove the manager, or the electorate may remove the manager through a recall election. Other city officers directly appointed by the council include the City Attorney, City Auditor, City Clerk, and Independent Police Auditor.[180] Like all cities and counties in the state, San Jose has representation in the state legislature.

Like all California cities except San Francisco, both the levels and the boundaries of what the city government controls are determined by the Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCO).[181] The goal of a LAFCO is to try to avoid uncontrolled urban sprawl. The Santa Clara County LAFCO has set boundaries of San Jose's "Sphere of Influence" (indicated by the blue line in the map near the top of the page) as a superset of the actual city limits (the yellow area in the map), plus parts of the surrounding unincorporated county land, where San Jose can, for example, prevent development of fringe areas to concentrate city growth closer to the city's core. The LAFCO also defines a subset of the Sphere as an 'Urban Service Area' (indicated by the red line in the map), effectively limiting development to areas where urban infrastructure (sewers, electrical service, etc.) already exists.

San Jose is the county seat of Santa Clara County.[182] Accordingly, many county government facilities are located in the city, including the office of the County Executive, the Board of Supervisors, the District Attorney's Office, eight courthouses of the Superior Court, the Sheriff's Office, and the County Clerk.[183]

State and federal

In the California State Senate, San Jose is split between the 10th, 15th, and 17th districts,[184] represented by Democrat Aisha Wahab, Democrat Dave Cortese, and Democrat John Laird respectively.

In the California State Assembly, San Jose is split between the 23rd, 24th, 25th, 26th, and 28th districts,[5] represented by Democrat Marc Berman, Democrat Alex Lee, Democrat Ash Kalra, Democrat Evan Low, and Democrat Gail Pellerin, respectively.

Federally, San Jose is split between California's 17th, 18th, and 19th congressional districts,[185] represented by Democrat Ro Khanna, Democrat Zoe Lofgren, and Democrat Jimmy Panetta, respectively.[186]

Several state and federal agencies maintain offices in San Jose. The city is the location of the Sixth District of the California Courts of Appeal.[187] It is also home to one of three courthouses of the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, the other two being in Oakland and San Francisco.[188]

Crime

Like most large cities, crime levels had fallen significantly after rising in the 1980s.[189] From 2002 to 2006, Morgan Quitno Press named San Jose the safest city in the United States with a population over 500,000 people.[190] Crime in San Jose had been lower than in other large American cities until 2013, when crime rates in San Jose climbed above California and U.S. averages.[191]

In 2021, SmartAsset ranked San Jose tied as the 10th safest city in the United States.[192] In 2020, violent crime per 100,000 people has been the lowest the city has seen in 2017 while the homicide rate has been the highest since 2016; property crime per 100,000 people has been the lowest the city has seen in over ten years.[193]

- 2021 mass shooting

On May 26, 2021, a mass shooting occurred at a Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA) rail yard in San Jose. Ten people were killed, including the gunman, 57-year-old VTA employee Samuel James Cassidy, who shot and killed himself.[194][195][196][197] The shooting led to a day-long suspension of light rail services in the area.[198][199] It is the deadliest mass shooting in the history of the San Francisco Bay Area.[200]

In June 2021, roughly a month following the shooting, San Jose became the first city in the United States to require gun owners to carry liability insurance after a unanimous vote by the city council.[201]

Education

Higher education

.jpg.webp)

San Jose is home to several colleges and universities. The largest is San José State University, which was founded by the California legislature in 1862 as the California State Normal School, and is the founding campus of the California State University (CSU) system. Located in downtown San Jose since 1870, the university enrolls approximately 35,000 students in over 250 different bachelor's, master's and doctoral degree programs.[202]

The school enjoys a good academic reputation, especially in the fields of engineering, business, computer science, art and design, and journalism, and consistently ranks among the top public universities in the western region of the United States.[203] San Jose State is one of only three Bay Area schools that fields a Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) Division I college football team; Stanford University and U.C. Berkeley are the other two.

California University of Management and Technology (CALMAT) offers many degree programs, including MBA, Computer Science, Information Technology. Most classes are offered both online and in the downtown campus. Many of the students are working professionals in the Silicon Valley.

The University of Silicon Valley is located in the Golden Triangle of North San Jose.

Lincoln Law School of San Jose and University of Silicon Valley Law School offer law degrees, catering to working professionals.

National University maintains a campus in San Jose.

The San Jose campus of Golden Gate University offers business bachelor and MBA degrees.

In the San Jose metropolitan area, Stanford University is in Stanford, California, Santa Clara University is in Santa Clara, California, and U.C. Santa Cruz is in Santa Cruz, California. Within the San Francisco Bay Area, other universities include U.C. Berkeley, U.C. San Francisco, U.C. Hastings College of Law, University of San Francisco, and California State University, East Bay.

The San Jose area's community colleges, San Jose City College, West Valley College, Mission College and Evergreen Valley College, offer associate degrees, general education units to transfer to CSU and UC schools, and adult and continuing education programs. The West campus of Palmer College of Chiropractic is also located in San Jose.

WestMed College is headquartered in San Jose and offers paramedic training, emergency medical technician training, and licensed vocational nursing programs.

The University of California operates Lick Observatory atop Mount Hamilton.

Western Seminary has one of its four campuses in San Jose, which opened on the campus of Calvary Church of Los Gatos in 1985. The campus relocated in 2010 to Santa Clara. Western is an evangelical, Christian graduate school that provides theological training for students who hope to serve in a variety of ministry roles including pastors, marriage and family therapists, educators, missionaries and lay leadership. The San Jose campus offers four master's degrees, and a variety of other graduate-level programs.[204]

National Hispanic University offered associate and bachelor's degrees and teaching credentials to its students, focusing on Hispanic students, until its closing in 2015.[205]

Primary and secondary education

Until the opening of Lincoln High School in 1943, San Jose students only attended San Jose High School. San Jose has 127 elementary, 47 middle, and 44 public high schools. Public education in the city is provided by four high school districts, fourteen elementary districts, and four unified school districts (which provide both elementary and high schools). In addition to the main San Jose Unified School District (SJUSD) and other Districts within San Jose such as the Alum Rock Unified School District and the East Side Union High School District, other nearby unified school districts of nearby cities are Milpitas Unified School District, Morgan Hill Unified School District, and Santa Clara Unified School District.

The public schools in San Jose declared bankruptcy in 1983; at that time, it was the largest US school district to declare bankruptcy.[206] Observers identified the reasons as a drop of 5,000 students in the preceding years, the difficulties imposed on school finances by Serrano v. Priest in 1968, the reduction of tax monies because of 1978 California Proposition 13, and the local teacher's union contract requiring a raise in pay.[207]

Private schools in San Jose are primarily run by religious groups. The Catholic Diocese of San Jose has the second-largest student population in Santa Clara County, behind only SJUSD; the diocese and its parishes operate several schools in the city, including five high schools.[208] Other private religious schools are Baptist,[209] non-denominational Protestant, and Wisconsin Synod Lutheran.[210] Secular private schools include Cambrian Academy and Harker School.

Libraries

The San José Public Library system is unique in that the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Library combines the collections of the city's system with the San Jose State University main library. In 2003, construction of the library, which now holds more than 1.6 million items, was the largest single library construction project west of the Mississippi, with eight floors that result in more than 475,000 sq ft (44,100 m2) of space with a capacity for 2 million volumes.[211]

The city has 23 neighborhood branches including the Biblioteca Latinoamericana ('Latin American Library') which specializes in Spanish language works.[212] The East San Jose Carnegie Branch Library, a Carnegie library opened in 1908, is the last Carnegie library in Santa Clara County still operating as a public library and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. As the result of a bond measure passed in November 2000, a number of brand new or completely reconstructed branches have been completed and opened. The yet-to-be-named brand new Southeast Branch is also planned, bringing the bond library project to its completion.[213]

The San Jose system (along with the university system) were jointly named as "Library of the Year" by Library Journal in 2004.[214]

Community services and utilities

San Jose is protected by the San Jose Police Department and San Jose Fire Department. Drinking water is supplied by the San José Municipal Water System (Muni Water) along with the privately owned San Jose Water Company and Great Oaks Water Company. The San José–Santa Clara Regional Wastewater Facility provides advanced wastewater treatment and reclaimed water.

Transportation

Like other American cities built mostly after World War II, San Jose is highly automobile-dependent, with 76 percent of residents driving alone to work and 12 percent carpooling in 2017.[215] The city set an ambitious goal to shift motorized trips to walking, bicycling, and public transit in 2009 with the adoption of its Envision San Jose 2040 General Plan. In 2018, the city extended these goals to 2050 with its San Jose Climate Smart plan.[216]

Public transit

Rail service to and from San Jose is provided by Amtrak (the Sacramento–San-Jose Capitol Corridor and the Seattle–Los-Angeles Coast Starlight), Caltrain (commuter rail service between San Francisco and Gilroy), ACE (commuter rail service to Pleasanton and Stockton), and the local VTA light rail system connecting downtown to Mountain View, Milpitas, Campbell, and Almaden Valley, operated by the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA). Historic streetcars from History Park operate on the light rail lines in downtown during holidays.

Long-term plans call for BART to be expanded to Santa Clara from the Berryessa/North San José station. Originally, the extension was to be built all at once, but due to the recession, sales tax revenue has dramatically decreased. Because of this, the extension will be built in two phases. Phase 1 extended service to San Jose with the completion of the Milpitas and Berryessa BART stations on June 13, 2020. In addition, San Jose will be a major stop on the future California High-Speed Rail route between Los Angeles and San Francisco.[217] Diridon Station (formerly Cahill Depot, 65 Cahill Street) is the meeting point of all regional commuter rail service in the area.[218] It was built in 1935 by the Southern Pacific Railroad, and was refurbished in 1994.

VTA also operates many bus routes in San Jose and the surrounding communities, as well as offering paratransit services to local residents. Additionally, the Highway 17 Express bus line connects central San Jose with Santa Cruz. Intercity bus providers include Greyhound, BoltBus, Megabus, California Shuttle Bus, TUFESA, Intercalifornias, Hoang, and USAsia.[219] FlixBus also services the city with a stop at 129 W San Carlos.

Air

_(2).jpg.webp)

San Jose is served by Norman Y. Mineta San Jose International Airport two mi (3.2 km) northwest of downtown, and by Reid-Hillview Airport of Santa Clara County, general aviation airport located in the eastern part of San Jose. San Jose residents also use San Francisco International Airport, a major international hub located 35 mi (56 km) to the northwest, and Oakland International Airport, another major international airport located 35 mi (56 km) to the north. The airport is also near the intersections of three major freeways, U.S. Route 101, Interstate 880, and State Route 87.

Highways

The San Jose area is served by a freeway system that includes three Interstate freeways and one U.S. Route. It is, however, the largest city in the country not served by a primary (one- or two-digit route number) Interstate; most of the Interstate Highway Network was planned by the early 1950s well before San Jose's rapid growth decades later.

U.S. 101 runs south to the California Central Coast and Los Angeles, and then runs north up near the eastern shore of the San Francisco Peninsula to San Francisco. I-280 also heads to San Francisco, but goes along just to the west of the cities of the San Francisco Peninsula. I-880 heads north to Oakland, running parallel to the southeastern shore of San Francisco Bay. I-680 parallels I-880 to Fremont, but then cuts northeast to the eastern cities of the San Francisco Bay Area.

.jpg.webp)

Several state highways also serve San Jose: SR 17, SR 85, SR 87 and SR 237. Additionally, San Jose is served by a system of county-wide expressways, which includes the Almaden Expressway, Capitol Expressway, San Tomas Expressway, and Lawrence Expressway.

Several regional transportation projects have been undertaken in recent years to manage congestion on San Jose freeways. This includes expanding State Route 87 to add more lanes near the downtown San Jose area.

The interchange for I-280 connecting with I-680 and U.S. 101 was named the Joe Colla Interchange.[221]

Major highways:

Bicycling

Central San Jose has seen a gradual expansion of bike lanes over the past decade, which now comprise a network of car-traffic-separated and buffered bike lanes. San Jose Bike Party is a volunteer-run monthly social cycling event that attracts up to 1,000 participants during summer months to "build community through bicycling". Fewer than one percent of city residents ride bicycles to work[222] as their primary mode of transportation, a statistic unchanged in the past ten years. Typically, between 3 and 5 residents are struck and killed by car drivers while bicycling on San Jose streets each year.[223]

Notable people

Sister cities

San Jose has one of the oldest Sister City programs in the nation. In 1957, when the city established a relationship with Okayama, Japan, it was only the third Sister City relationship in the nation, which had begun the prior year. The Office of Economic Development coordinates the San Jose Sister City Program which is part of Sister Cities International. As of 2014, there are eight sister cities:[224][225]

- Okayama, Japan (established on May 26, 1957)[226]

- San José, Costa Rica (1961)

- Veracruz, Mexico (1975)

- Tainan, Taiwan (1977)

- Dublin, Ireland (1986)[227]

- Yekaterinburg, Russia (1992)

- Pune, India (1992)

- Guadalajara, Mexico (2014)[228][229]

See also

References

- "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.