Church of Saint George and Mosque of Al-Khadr

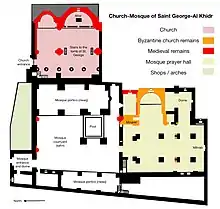

The Church of Saint George and the Mosque of Al-Khidr in Lod, Israel, are connected houses of worship situated on top of and embedding the remains of a Byzantine- and Crusader-period complex. The church crypt contains a sarcophagus venerated as the tomb of the fourth-century Christian martyr Saint George, who is frequently associated with the Muslim holy figure Al-Khidr.[1]

| Church-Mosque of Saint George | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Greek Orthodox and Sunni Islam |

| Location | |

| Location | Lod, Israel |

| Geographic coordinates | 31°57′10.8″N 34°53′58.15″E |

| Architecture | |

| Completed | various |

The 13th-century Mamluk-period mosque contains the primary elements of both the Byzantine ecclesiastic complex and the subsequent Crusader cathedral.[2][3] The 19th-century Greek Orthodox church (Arabic: كنيسة القديس جيورجوس or كنيسة مار جريس, Hebrew: כנסיית גאורגיוס הקדוש קוטל הדרקון, "Church of Saint George, slayer of the dragon")[3] is based on the partially rebuilt Crusader-period church,[3] which had itself been built over part of the remains and footprint of the Byzantine-period predecessor.[2]

History

Byzantine establishment

The church of Saint George was first established in Lod by the Byzantines and stood in the 5th-7th centuries.[2] It was probably shaped as a basilica whose three aisles terminated at the east end in semi-circular apses.[2] Beside the main church, the complex also contained a second, smaller one just southwest of it.[2] The Christian site was destroyed in 614 by the Sasanids during the war which led to them conquering Jerusalem.

The Byzantine basilica may have had just one apse with two irregular pastophoria (chambers).[4]

Crusader cathedral

The Crusaders established their cathedral at the exact site of the main Byzantine church, reusing some of its surviving masonry, and having the same internal measurements of 47 metres east to west, and 24 metres north to south.[2] The three-aisled basilica also terminated in three semi-circular apses, with the second of five bays forming the transept.[2] In 1177, a detachment of Saladin's army attacked the town and the inhabitants survived by taking refuge on the roof of the fortified church, which seems to indicate that by this time it had a stone roof.[2]

After reconquering the land from the Crusaders in the aftermath of the 1187 Battle of Hattin, Saladin had the cathedral of Lydda and castle of Ramla demolished in 1191.[2] The territory around Lydda changed hands repeatedly during the next eight decades, and the state of the church during this time is not clearly documented, with nothing to support the notion that it was rebuilt by Richard the Lionhearted.[2] It seems that the Greek Orthodox continued using the still standing eastern part of the church, with the choir and the tomb of St George, possibly along with the smaller buildings southwest of the ruined cathedral.[2] In 1266 Lydda fell to the Mamluk sultan Baibars.[2] Clermont-Ganneau speculated that the Frankish materials present in secondary use at the nearby Jindas Bridge (1273) were taken from the demolished part of the Lydda church,[2] which Adrian Boas sees as part of the wider Mamluk custom of marking the triumph over the Christians by recycling their masonry for their own constructions.[5]

Mamluk mosque

During the Mamluk period, the ruined western part of the Crusader church has been converted into a congregational mosque, the earliest mention of which comes from the early 15th century.[2] The remains of the smaller Byzantine basilica southwest of the main church, including its apse, were incorporated into the mosque's prayer hall;[2] today a pillar that once stood in the nave of the basilica remains inside the mosque prayer hall with an inscription in Greek.[2] Above the entrance to the mosque is an inscription dating its construction to June 1269 (Ramadan 667), as instructed by Baibars.

The northern façade of the mosque building faces the courtyard (sahn), and makes use of the south wall of the Crusader church. The mosque itself is built as a length hall divided into three by two rows of four pillars each. Its ceiling is vaulted and made in the shape of a cross. On the eastern side of the prayer hall remains a remnant of a Byzantine apse. Beneath the mosque are underground halls, built by the Crusaders and used as reservoirs for the church and city residents. The mosque and minaret were mentioned by Felix Fabri in the 1480s:

"The rest of the church has been cut off from the choir by a wall, and they have made that part of it into a fair mosque in honour of Mahomet, and adorned it with a lofty tower. The door stood over against us, so that we could see into the courtyard of the mosque, and into the mosque itself, and it was like Paradise for cleanliness and beauty."[6]

In the Ottoman period, the entrance to the courtyard of the mosque was located on its western wall, but it was later moved to its northern side.

19th-century church

.jpg.webp)

The current Church of St. George incorporates only the northeast corner of the original site. During the second part of the nineteenth century, the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem received permission from the Ottoman authorities to build a church on the site of the medieval ruins. The 19th-century church was built over the remains of the 12th-century Crusader structure, occupying the east end of its nave and northern aisle, from which the corresponding two apses survive.[2]

The Ottoman authorities stipulated that part of the church plot be incorporated in the mosque courtyard.[7] The southern part of the Crusader church dictated the shape of the mosque courtyard.[2]

The church crypt contains a sarcophagus[3] venerated as a symbolic tomb of St George.[1]

Gallery

Combined site

1487 drawing of ruined church over St George's tomb and Mosque by Konrad von Grünenberg

1487 drawing of ruined church over St George's tomb and Mosque by Konrad von Grünenberg_-_Bruyn_Cornelis_De_-_1714.jpg.webp) 1714 drawing of ruined church over St George's tomb by Cornelis de Bruijn

1714 drawing of ruined church over St George's tomb by Cornelis de Bruijn_-_Chrysanthus_Of_Bursa_-_1807.jpg.webp) 1807

1807 1866 (east end ruins, viewed from the south)

1866 (east end ruins, viewed from the south).jpg.webp) 1857

1857.jpg.webp) 1870

1870.jpg.webp) 1873-74

1873-74 1910

1910 c.1920

c.1920_en_de_El_Chodr_moskee_(r)_in_Lydda_(Lod)%252C_Bestanddeelnr_255-3108.jpg.webp) 1948-49

1948-49 2022

2022

Mosque

Courtyard, looking towards the entrance

Courtyard, looking towards the entrance Minaret close up

Minaret close up Interior of the prayer hall, including mihrab

Interior of the prayer hall, including mihrab Pillars showing Byzantine remains above

Pillars showing Byzantine remains above Inscription at mosque entrance

Inscription at mosque entrance

Church

.jpg.webp) Iconostasis and chandelier

Iconostasis and chandelier_02.JPG.webp) The symbolic sarcophagus of St George from the crypt

The symbolic sarcophagus of St George from the crypt_04_-_particolare_del_bassorilievo.JPG.webp) Bas-relief on the sarcophagus

Bas-relief on the sarcophagus

Bibliography

- Clermont-Ganneau, C.S. (1896). [ARP] Archaeological Researches in Palestine 1873-1874, translated from the French by J. McFarlane. Vol. 2. London: Palestine Exploration Fund. (pp. 102-109)

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (pp. 267-8)

- Guérin, V. (1868). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale. (p. 330)

- Moudjir ed-dyn (1876). Sauvaire (ed.). Histoire de Jérusalem et d'Hébron depuis Abraham jusqu'à la fin du XVe siècle de J.-C. : fragments de la Chronique de Moudjir-ed-dyn. (pp. 210-211)

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. (pp. 49-55)

See also

- Saint George in devotions, traditions and prayers

- List of churches under the patronage of Saint George

- St. George's Cathedral, Jerusalem, an Anglican church in Jerusalem

- Monastery of Saint George, al-Khader, a Greek Orthodox monastery near Bethlehem

- Dome of al-Khidr, also known as the Dome of St. George

- Religion in Israel

References

- Collins, M. (2018). St. George and the Dragons: The Making of English Identity. Fonthill Media. pp. 406-408 [mainly 408]. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

In Lod and in Al-Khadr, shrines to St George consist of a single site where a church has been built alongside a mosque.

- Pringle, D. (1998). "Lydda (nos. 137-8)". The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. Vol. II: L-Z (excluding Tyre). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39037-0. Retrieved 22 December 2022. (pp. 9 ff, see 9-15)

- "Excursions in Terra Santa". Franciscan Cyberspot. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- Margalit, S., "The Bi-Apsidal Churches in Palestine, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Cyprus", Liber Annuus 40 (1990): 321-334, pls. 45-48.

- Boas, Adrian J. (19 October 2020). On a Saint, a Dragon, a Church, a Bridge, a Cat, a Rat and a Statement. Accessed 21 Dec. 2022.

- Felix Fabri, p.257

- Mauss, Christophe-Edouard (1892). "L'Église de Saint-Jérémie à Abou-Gosch (Emmaüs de Saint Luc et Castellum de Vespasien) avec une étude sur le stade au temps de Saint Luc et de Flavius Josèphe". Revue Archéologique. E. Leroux. 19: 223–71. JSTOR 41729389.

En 1870, le wali de Damas et le consul général de France à Beyrouth étaient réunis à Jérusalem pour régler un différend grave qui s'était élevé entre le consulat français et la municipalité, à la suite de l'envahissement du couvent de Sion par les agents de l'autorité locale. L'affaire une fois réglée, les deux commissaires repartirent pour Jaffa et s'arrêtèrent à Lydda afin d'examiner une question, depuis longtemps pendante entre les Grecs et les Latins, et relative à la propriété des ruines de l'église Saint-Georges. Les Grecs soutenaient que les ruines de Lydda remontainent au Vie siècle, époque à laquelle une première église dediee a saint Georges fut édifiée à Lydda. Les Latins appuyaient leurs revendications sur ce fait que les ruines de Lydda ne pouvaient, historiquement, remonter plus haut que l'époque des Croisades. Pour éclairer sa religion, le commissaire français no [?] descendre à Lydda, et de lui donner notre avis sur l'é [?] bable [?] de la construction de l'église contestée. L'étude des ruines a démontré qu'il existe à Lydda fices [édifice?] absolument distincts dont le plus ancien, conver quée à une époque indéterminée, peut être attribué au ainsi que le démontre la forme de certains profils et qui sont encore visibles. Ce serait donc à cette mosquée qu'on pourrait appliquer la dition [?] conservée par les Grecs d'une église Saint-George sous l'empereur Justinien... Reconstruite encore une fois dans la deuxième moitié du XIIe siècle en dehors de V [l'?] ancienne église, la cathédrale de Lydda fut renversée par ordre de Saladin après la chute du royaume franc. Ce sont les ruines de cette dernière église qui ont été adjugées au clergé grec, en 1870, par le commissaire ottoman. Quant à l'édifice byzantin, qui n'avait été qu'en partie détruit à l'approche des Croisés, il fut converti en mosquée. La cour aux ablutions fut prise aux dépens de l'église du XIIe siècle, et le minaret construit dans l'angle nord-ouest de l'église byzantine... Après leur prise de possession, en 1870, les Grecs de Lydda s'empressèrent d'englober les ruines dans une bâtisse nouvelle, qui, par le fait, constitue une cinquième reconstruction de l'église Saint-Georges. L'église du Vie siècle est donc encore debout, en partie : c'est la mosquée. A chacune des démolitions, on respecta la partie orientale du monument, probablement parce qu'elle était la plus difficile à renverser.

External links

- "St George's Church, Lod". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- "Church of St. George in Lod". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- "St George's Church, Lod". Archived from the original on 21 January 2005.

- "Dor Guez, St George Church, video still". 2009. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011.

- Photos of the Church at the Manar al-Athar photo archive