Monster movie

A monster movie, monster film, creature feature or giant monster film is a film that focuses on one or more characters struggling to survive attacks by one or more antagonistic monsters, often abnormally large ones. The film may also fall under the horror, comedy, fantasy, or science fiction genres. Monster movies originated with adaptations of horror folklore and literature.

Traditional concepts

The most common aspect of a monster movie is the struggle between a human collective of protagonists against one or more monsters, who often serve as the antagonistic force. In Japanese cinema, giant monsters known as kaiju often take up this role.

The monster is often created by a folly of mankind – an experiment gone wrong, the effects of radiation or the destruction of habitat. Or the monster is from outer space, has been on Earth for a long time with no one ever seeing it, or released (or awakened) from a prison of some sort where it was being held.

The monster is usually a villain, but can be a metaphor of humankind's continuous destruction; giant monsters since the introduction of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) have for a time been considered a symbol of atomic warfare, for instance. On the contrary, Godzilla began in this fashion yet as time moved on his reputation quickly grew into that of a cultural icon to the Japanese, as much as Superman is a cultural symbol to America, with a number of films presenting Godzilla as a sort of protagonist who helps protect humans from other, more malevolent monsters.

The attempts of the humans to destroy the monster would at first be the usage of an opposing military force – an attempt that would antagonize the monster even more and prove useless (a cliché associated with the genre). The Godzilla series utilized the concept of a superweapon built by Japanese scientists to suppress him or any of the monsters he fights.

Historically, monsters have been depicted using stop motion animation, puppets, or creature suits. In the modern day, many monster movies have used CGI monsters.

History

Early monster films (1915–1954)

The first feature-length films to include what are regarded as monsters were often classed as horror or science fiction films. The 1915 German silent film The Golem, directed by Paul Wegener, is one of the earliest examples of film to include a creature. The German Expressionist Nosferatu in 1922, and the depiction of a dragon in Fritz Lang's Die Nibelungen in 1924, followed tradition. In the 1930s, American film studios began to produce more successful films of this type, usually based on Gothic tales such as Dracula and Frankenstein in 1931, both heavily influenced by German Expressionism, followed by The Mummy (1932) and The Invisible Man (1933). Classified as horror films, they included iconic monsters.

Special effects animator Willis O'Brien worked on the 1925 fantasy adventure The Lost World, based on the novel of the same name. The book and film featured dinosaurs, the basis for many future movies. He began work on a similar film known as Creation in 1931, but the project was never completed.[1] Two years later, O'Brien produced special effects for the 1933 RKO film King Kong, directed by Merian C. Cooper. Since then, King Kong has not only become one of the most famous examples of a monster movie, but also is considered a landmark film in the history of cinema. The monster King Kong became a cultural icon, being featured in many other films and media since then.[2]

King Kong went on to inspire many other films of its genre and aspiring animators. A notable example was Ray Harryhausen,[3] who would work with Willis O’Brien on Mighty Joe Young in 1949. Following the re-release of King Kong in 1952, Harryhausen would later work on The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms in 1953. The film was about a fictional dinosaur, a Rhedosaurus, that was awakened from frozen ice in the Arctic Circle by an atomic bomb test. It is considered to be the film which kick-started the 1950s wave of “creature features” and the concept of combining nuclear paranoia with the genre.[4] Such films at the time included Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), Them! (1954), It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955), Tarantula! (1955), The Deadly Mantis (1957) and 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957). The Giant Behemoth (1959) was an unacknowledged remake of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms.

Kaiju era (1954–1975)

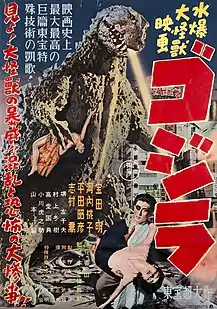

During the 1950s, Japanese film studio Toho produce their first successful kaiju films. Their first successful kaiju film was Godzilla (1954), which adapted the nuclear concept from The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms from a Japanese perspective, rooted in real-life Japanese historical events, such as the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 and the Daigo Fukuryū Maru incident in 1954.[5][6] The film's success spawned the Godzilla franchise, the longest-running film franchise in history. The titular monster has become a cultural icon, and one of the most recognizable monsters in cinema history. It also inspired a wave of kaiju films, such as Rodan from this time.

Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (1956), a re-edited Americanized version of Godzilla for the North American market, notably inspired Steven Spielberg when he was a youth. He described Godzilla as "the most masterful of all the dinosaur movies" because "it made you believe it was really happening."[7]

A parallel development during this era was the rise of the Z movie, films made outside the organized motion picture industry with ultra-low budgets. Grade-Z monster movies such as Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959) and The Creeping Terror (1964) are often listed among the worst films ever made because of their inept acting and amateurish special effects.

After 1960, American monster movies were less popular, yet were still produced. However, Japanese kaiju films were popular during this decade. In 1962, King Kong vs. Godzilla was a kaiju film produced by Toho featuring both Godzilla and King Kong. In 1965, Japanese studio Kadokawa Pictures started their own kaiju franchise to rival that of Godzilla, in the form of Gamera.

Ray Harryhausen continued to work on a number of films such as The Valley of Gwangi (1969), while Toho continued production of Godzilla and other kaiju films like Mothra (1961).

The Monster Times film magazine was founded in 1972. In 1973, The Monster Times conducted a poll to determine the most popular screen monster. Godzilla was voted the most popular movie monster, beating Count Dracula, King Kong, the Wolf Man, the Mummy, the Creature from the Black Lagoon, and Frankenstein's monster.[8]

Spielberg era (1975–1998)

In 1975, Steven Spielberg directed Jaws, which while labeled as a "thriller", features a large, animatronic great white shark. Jaws was an aquatic monster movie influenced by earlier monster films such as King Kong and Godzilla.[9] Jaws is one of the few monster movies based on a real incident: the New Jersey shark-attacks of 1916 (from which Peter Benchley got the idea for the story). Director John Guillermin remade King Kong in 1976. The xenomorph alien had its first appearance in the 1979 science-fiction/horror film Alien, directed by Ridley Scott. That was the same year when magazine Fangoria started being published, in response to the popularity of this genre.

Since the mid-1970s, with Mel Brooks' Young Frankenstein, and into the 1980s, monster movies like Larry Cohen's Q, the Winged Serpent (1982), Tom Holland's Fright Night (1985), George Romero's Creepshow (1982) and Ron Underwood's Tremors (1990) used comedy as a scaring device. Just before the technological revolution that made possible to create digital special effects thanks to CGI, the last generation of SFX artists impressed many with the quality and realism of their creations: Rick Baker, Stan Winston and Rob Bottin are among the most remarkable names in the industry.

1993 saw the release of Jurassic Park, based on the 1990 novel of the same name by Michael Crichton and directed by Steven Spielberg, which set a new benchmark in the genre with innovative use of CGI and tried-and-tested animatronics to recreate dinosaurs. The film was also influenced by Godzilla.[7] Jurassic Park was an enormous critical and commercial success and at one point held the title of the highest-grossing film of all time.

The success of Jurassic Park and its five sequels, The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), Jurassic Park III (2001), Jurassic World (2015), Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (2018) and Jurassic World Dominion (2022), made sure that dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex and the Velociraptor established themselves in the public psyche. The movies also helped generate renewed interest in paleontology. While the films showed allegedly authentic dinosaurs which had been recreated by genetic engineering and could be understood as science fiction, advanced contemporary animation technology made it also possible to revive medieval legends about dragons. The successful feature film Dragonheart (1996) showed a friendly dragon voiced by Sean Connery.

Modern era (1998–present)

Traditional monster movies re-emerged to a wider audience during the late 1990s. An American remake of Godzilla was made in 1998. The Godzilla featured in that film was considerably different from the original and many Godzilla fans disliked it, but it was a box office success. In 2002, a French monster film Brotherhood of the Wolf (2001) became the second-highest-grossing French-language film in the United States in the last two decades.[10] In 2004, Godzilla was temporarily retired following Godzilla: Final Wars. Director Peter Jackson, inspired by the original King Kong and Ray Harryhausen films,[3] remade King Kong in 2005, which was both a critical and commercial success. In 2006, a South Korean monster film, The Host, involved more political overtones than most of its genre.[11]

The 2008 monster movie, Cloverfield, a story in the vein of classic monster movies, focuses entirely on the perspective and reactions of the human cast and is regarded by some as a look at terrorism and the September 11 attacks metaphorically.[12] The following year The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep (2007) was released, in which the legendary Loch Ness Monster is portrayed as a playful creature menaced by overly aggressive humans. The British Independent Film Award-winning film Monsters, in a manner similar to Cloverfield, presented the story of a monster epidemic from the perspective of the humans affected by it. Although not entirely focused on monsters, blockbusters such as The Avengers and Prometheus included scenes that featured monsters posing threats to the protagonists.

In 2013, Warner Bros. and Legendary Pictures released the Guillermo del Toro film Pacific Rim. Though the film was heavily inspired by the kaiju and Mecha anime genres, del Toro wished to create something original with the film rather than to reference previous work. The film was a moderate success in the United States but a box office hit overseas. It received generally positive reviews with significant praise for the film's special effects. A sequel, Pacific Rim Uprising, was released in 2018.

In 2014, Warner Bros. and Legendary Pictures released Godzilla, a reboot of the Godzilla franchise directed by Gareth Edwards. Legendary originally intended to produce a trilogy with Edwards attached to direct all films.[13] Shortly afterwards, Legendary announced a shared cinematic universe between Godzilla and King Kong, titled MonsterVerse.[14] Two years later in 2016, Toho rebooted the Godzilla franchise with Shin Godzilla.[15] Kong: Skull Island was released in March 2017, a reboot of the King Kong franchise and second film in Legendary's MonsterVerse. The third film in the MonsterVerse, Godzilla: King of the Monsters was released on May 31, 2019. Michael Dougherty directed the film and featured Rodan, Mothra, and King Ghidorah.[16] The fourth film in the MonsterVerse, Godzilla vs. Kong, was released on March 31, 2021.[17] It is directed by Adam Wingard.[18]

See also

References

- Stephen Jones (1995). The Illustrated Dinosaur Movie Guide. Titan Books. p. 26.

- Stephen Jones (1995). The Illustrated Dinosaur Movie Guide. Titan Books. pp. 24–25.

- "Ray Harryhausen: The Early Years Collection – Interview". Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- Stephen Jones (1995). The Illustrated Dinosaur Movie Guide. Titan Books. p. 42.

- Robert Hood. "A Potted History of Godzilla". Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- "Gojira / Godzilla (1954) Synopsis". Archived from the original on 2007-12-24. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan's Favorite Mon-star: The Unauthorized Biography of "The Big G". ECW Press. pp. 15–7. ISBN 9781550223484.

- Kogan, Rick (September 15, 1985). "'It Was A Long Time Coming, But Godzilla, This Is Your Life". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Freer, Ian (2001). The Complete Spielberg. Virgin Books. p. 48. ISBN 9780753505564.

- "Little pictures have a big year", Los Angeles Times, 3 January 2003

- Kevin O'Donovan (2007-10-07). "The Host: Monster Movie with a Message at cinekklesia". Archived from the original on 2007-12-08. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- Chris Haire (2008-01-23). "The 9/11 porn of Cloverfield". Charleston City Paper. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- Kit, Borys (May 22, 2014). "'Star Wars' Spinoff Hires 'Godzilla' Director Gareth Edwards (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- "Legendary and Warner Bros. Pictures Announce Cinematic Franchise Uniting Godzilla, King Kong and Other Iconic Giant Monsters" (Press release). Legendary Pictures. October 14, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- "Toho Announces New Japanese Godzilla Flick for 2016". Dread Central. 2014-12-08. Retrieved 2022-03-08.

- "Warner Bros. Pictures' and Legendary Pictures' MonsterVerse Kicks Into Gear as the Next Godzilla Feature Gets Underway" (Press release). June 19, 2017.

- Busch, Jenna (May 3, 2017). "Godzilla vs. Kong and More Release Date Changes From Warner Bros". Coming Soon. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- Kit, Borys (May 30, 2017). "'Godzilla vs. Kong' Finds Its Director With Adam Wingard (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved May 30, 2017.