Nosferatu

Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (German: Nosferatu – Eine Symphonie des Grauens) is a 1922 silent German Expressionist vampire film directed by F. W. Murnau and starring Max Schreck as Count Orlok, a vampire who preys on the wife (Greta Schröder) of his estate agent (Gustav von Wangenheim) and brings the plague to their town.

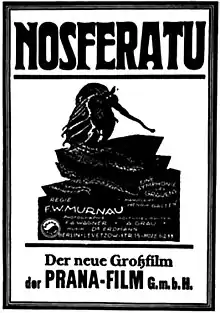

| Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror | |

|---|---|

Newspaper advert | |

| Directed by | F. W. Murnau[1] |

| Screenplay by | Henrik Galeen |

| Based on | Dracula by Bram Stoker |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography |

|

| Music by | Hans Erdmann (1922 premiere)[1] |

Production company | Prana Film |

| Distributed by | Film Arts Guild |

Release date |

|

Running time | 63–94 minutes, depending on version and transfer speed[1] |

| Country | Germany |

| Languages |

|

Nosferatu was produced by Prana Film and is an unauthorized and unofficial adaptation of Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula. Various names and other details were changed from the novel, including Count Dracula being renamed Count Orlok. Although those changes are often represented as a defense against copyright infringement,[3] the original German intertitles acknowledged Dracula as the source. Film historian David Kalat states in his commentary track that since the film was "a low-budget film made by Germans for German audiences... setting it in Germany with German-named characters makes the story more tangible and immediate for German-speaking viewers".[4]

Even with several details altered, Stoker's heirs sued over the adaptation, and a court ruling ordered all copies of the film to be destroyed. However, several prints of Nosferatu survived,[1] and the film came to be regarded as an influential masterpiece of cinema and the horror genre.[5][6]

Plot

In 1838, in the fictional German town of Wisborg,[1][7] Thomas Hutter is sent to Transylvania by his employer, estate agent Herr Knock, to visit a new client, Count Orlok, who plans to buy a house across from Hutter's own home. While embarking on his journey, Hutter stops at an inn in which the locals are frightened by the mere mention of Orlok's name.

Hutter rides on a coach to a castle, where he is welcomed by Count Orlok. When Hutter is eating dinner and accidentally cuts his thumb, Orlok tries to suck the blood out, but his repulsed guest pulls his hand away. Hutter wakes up the morning after to find fresh punctures on his neck, which he attributes to mosquitoes. That night, Orlok signs the documents to purchase the house and notices a photo of Hutter's wife, Ellen, remarking that she has a "lovely neck." Reading a book about vampires that he took from the local inn, Hutter starts to suspect that Orlok is a vampire. With no way to bar the door, he cowers in his room as midnight approaches. The door opens by itself and Orlok enters, and Hutter hides under the bed covers and falls unconscious. Meanwhile, his wife awakens from her sleep and, in a trance, walks onto her balcony's railing, which gets the attention of her friend Harding. When the doctor arrives, she shouts Hutter's name and can apparently see Orlok in his castle who is threatening her unconscious husband.

The next day, Hutter explores the castle, only to retreat back into his room after he finds the coffin in which Orlok is resting dormant in the crypt. Hours later, Orlok piles up coffins on a coach and climbs into the last one before the coach departs, and Hutter rushes home after learning that. The coffins are taken aboard a schooner, where the sailors discover rats in the coffins. All of the ship's crew later die, and Orlok takes control. When the ship arrives in Wisborg, Orlok leaves unobserved, carries one of his coffins and moves into the house that he purchased.

Many deaths in the town follow after Orlok's arrival, which the town's doctors blame on an unspecified plague caused by the rats from the ship. Ellen reads the book that Hutter found; it claims that a vampire can be defeated if a pure-hearted woman distracts the vampire with her beauty and offers him her blood of her own free will. She decides to sacrifice herself. She opens her window to invite Orlok in and pretends to fall ill so that she can send Hutter to fetch Professor Bulwer, a physician. After he leaves, Orlok enters and drinks her blood, but the sun rises, which causes Orlok to vanish in a puff of smoke. Ellen lives just long enough to be embraced by her grief-stricken husband.

The last scene shows Count Orlok's destroyed castle in the Carpathian Mountains.

Cast

- Max Schreck as Count Orlok

- Gustav von Wangenheim as Thomas Hutter

- Greta Schröder as Ellen Hutter

- Alexander Granach as Knock

- Georg H. Schnell as Shipowner Harding

- Ruth Landshoff as Ruth

- John Gottowt as Professor Bulwer

- Gustav Botz as Professor Sievers

- Max Nemetz as The Captain of The Empusa

- Wolfgang Heinz as First Mate of The Empusa

- Hardy von Francois as Mental Hospital Doctor

- Albert Venohr as Sailor Two

- Guido Herzfeld as Innkeeper

- Karl Etlinger as Student with Bulwer

- Fanny Schreck as Hospital Nurse

Themes

Nosferatu has been noted for its themes regarding fear of the Other, as well as for possible anti-Semitic undertones,[1] both of which may have been partially derived from the Bram Stoker novel Dracula, upon which the film was based.[8] The physical appearance of Count Orlok, with his hooked nose, long claw-like fingernails, and large bald head, has been compared to stereotypical caricatures of Jewish people from the time in which Nosferatu was produced.[9] His features have also been compared to those of a rat or a mouse, the former of which Jews were often equated with.[10][11] Orlok's interest in acquiring property in the German town of Wisborg, a shift in locale from the Stoker novel's London, has also been analyzed as preying on the fears and anxieties of the German public at the time.[12] Professor Tony Magistrale opined that the film's depiction of an "invasion of the German homeland by an outside force [...] poses disquieting parallels to the anti-Semitic atmosphere festering in Northern Europe in 1922."[12]

When the foreign Orlok arrives in Wisborg by ship, he brings with him a swarm of rats which, in a deviation from the source novel, spread the plague throughout the town.[11][13] This plot element further associates Orlok with rodents and the idea of the "Jew as disease-causing agent".[9][11] Writer Kevin Jackson has noted that director F. W. Murnau "was friendly with and protective of a number of Jewish men and women" throughout his life, including Jewish actor Alexander Granach, who plays Knock in Nosferatu.[14] Additionally, Magistrale wrote that Murnau, being a homosexual, would have been "presumably more sensitive to the persecution of a subgroup inside the larger German society".[11] As such, it has been said that perceived associations between Orlok and anti-Semitic stereotypes are unlikely to have been conscious decisions on the part of Murnau.[11][14]

Production

The studio behind Nosferatu, Prana Film, was a short-lived silent-era German film studio founded in 1921 by Enrico Dieckmann and occultist artist Albin Grau,[1] named after a Theosophical journal which was itself named for the Hindu concept of prana.[4] Although the studio's intent was to produce occult- and supernatural-themed films, Nosferatu was its only production,[15] as it declared bankruptcy shortly after the film's release.

Grau claimed he was inspired to shoot a vampire film by a war experience: in Grau's apocryphal tale, during the winter of 1916, a Serbian farmer told him that his father was a vampire and one of the undead.[16]

Diekmann and Grau gave Henrik Galeen, a disciple of Hanns Heinz Ewers, the task to write a screenplay inspired by the Dracula novel, although Prana Film had not obtained the film rights. Galeen was an experienced specialist in dark romanticism; he had already worked on The Student of Prague (1913), and the screenplay for The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920). Galeen set the story in the fictional north German harbour town of Wisborg. He changed the characters' names and added the idea of the vampire bringing the plague to Wisborg via rats on the ship, and left out the Van Helsing vampire hunter character. Galeen's Expressionist style screenplay was poetically rhythmic, without being so dismembered as other books influenced by literary Expressionism, such as those by Carl Mayer. Lotte Eisner described Galeen's screenplay as "voll Poesie, voll Rhythmus" ("full of poetry, full of rhythm").[17]

Filming began in July 1921, with exterior shots in Wismar. A take from Marienkirche's tower over Wismar marketplace with the Wasserkunst Wismar served as the establishing shot for the Wisborg scene. Other locations were the Wassertor, the Heiligen-Geist-Kirche yard and the harbour. In Lübeck, the abandoned Salzspeicher served as Nosferatu's new Wisborg house, the one of the churchyard of the Aegidienkirche served as Hutter's, and down the Depenau a procession of coffin bearers bore coffins of supposed plague victims. Many scenes of Lübeck appear in the hunt for Knock, who ordered Hutter in the Yard of Füchting to meet Count Orlok. Further exterior shots followed in Lauenburg, Rostock and on Sylt. The exteriors of the film set in Transylvania were actually shot on location in northern Slovakia, including the High Tatras, Vrátna dolina, Orava Castle, the Váh River, and Starý Castle.[18] The team filmed interior shots at the JOFA studio in Berlin's Johannisthal locality and further exteriors in the Tegel Forest.[1]

For cost reasons, cameraman Fritz Arno Wagner only had one camera available, and therefore there was only one original negative.[19] The director followed Galeen's screenplay carefully, following handwritten instructions on camera positioning, lighting, and related matters.[17] Nevertheless, Murnau completely rewrote 12 pages of the script, as Galeen's text was missing from the director's working script. This concerned the last scene of the film, in which Ellen sacrifices herself and the vampire dies in the first rays of the sun.[20][21] Murnau prepared carefully; there were sketches that were to correspond exactly to each filmed scene, and he used a metronome to control the pace of the acting.[22]

.jpg.webp) Wismar Wassertor as harbour gate of Wisborg (Photo 1907)

Wismar Wassertor as harbour gate of Wisborg (Photo 1907) Churchyard Aegidienkirchhof as Hutter's house (Photo 1909)

Churchyard Aegidienkirchhof as Hutter's house (Photo 1909).jpg.webp) Wismar Wasserkunst (Photo ca 1900)

Wismar Wasserkunst (Photo ca 1900) Yard of Heiligen-Geist-Kirche in Wismar for Hutter's departure (Photo 1970)

Yard of Heiligen-Geist-Kirche in Wismar for Hutter's departure (Photo 1970) Old oak of Israelsdorf 1892

Old oak of Israelsdorf 1892 Starý hrad castle ruins as Orlok's dilapidated castle at the end of the film

Starý hrad castle ruins as Orlok's dilapidated castle at the end of the film

Music

The original score was composed by Hans Erdmann and performed by an orchestra at the film's Berlin premiere. However, most of the score has been lost, and what remains is only a partial adapted suite.[1] Thus, throughout the history of Nosferatu screenings, many composers and musicians have written or improvised their own soundtrack to accompany the film. For example, James Bernard, composer of the soundtracks of many Hammer horror films in the late 1950s and 1960s, wrote a score for a reissue.[1][23] Bernard's score was released in 1997 by Silva Screen Records. A version of Erdmann's original score reconstructed by musicologists and composers Gillian Anderson and James Kessler was released in 1995 by BMG Classics, with several missing sequences composed anew, in an attempt to match Erdmann's style. An earlier reconstruction by German composer Berndt Heller has many additions of unrelated classical works.[1] In 2022, the New York Times wrote about Dutch composer Jozef van Wissem's new score and record release for Nosferatu. Beginning with a solo played on the lute, his performance incorporates electric guitar and distorted recordings of extinct birds, graduating from subtlety to gothic horror. "My soundtrack goes from silence to noise over the course of 90 minutes," he said, culminating in "dense, slow death metal."[24]

Deviations from the novel

The story of Nosferatu is similar to that of Dracula and retains the core characters: Jonathan and Mina Harker, Count Dracula, and so on. It omits many of the secondary players, however, such as Arthur and Quincey and changes the names of those who remain. The setting has been transferred from Britain in the 1890s to Germany in 1838.[1]

In contrast to Count Dracula, Orlok does not create other vampires but kills his victims, which causes the townsfolk to blame the plague which ravages the city. Orlok also must sleep by day, as sunlight would kill him, but the original Dracula is only weakened by sunlight. Orlok is also believed to have been created by Belial, the lieutenant demon of Satan, and Count Dracula is revealed to have been a former voivode killed in battle before returning as a vampire. The ending is also substantially different from the Dracula novel since the count is ultimately destroyed at sunrise when the Mina analogue sacrifices herself to him.[1] The town called "Wisborg" in the film is in fact a mix of Wismar and Lübeck; in other versions of the film, the name of the city is changed, for unknown reasons, back to "Bremen".[25]

Release

Shortly before the premiere, an advertisement campaign was placed in issue #21 of the magazine Bühne und Film, with a summary, scene and work photographs, production reports, and essays, including a treatment on vampirism by Albin Grau.[26] Nosferatu opened in the Netherlands on 16 February 1922 at the Hague Flora and Olympia cinemas.[27] Nosferatu premiered in Germany on 4 March 1922 in the Marmorsaal of the Berlin Zoological Garden. This was planned as a large society evening entitled Das Fest des Nosferatu (Festival of Nosferatu), and guests were asked to arrive dressed in Biedermeier costume. The German cinema premiere itself took place on 15 March 1922 at Berlin's Primus-Palast.[1]

The 1930s sound version Die zwölfte Stunde – Eine Nacht des Grauens (The Twelfth Hour: A Night of Horror), which is less commonly known, was a completely unauthorized and re-edited version of the film. It was released in Vienna, Austria on 16 May 1930 with sound-on-disc accompaniment and a recomposition of Hans Erdmann's original score by Georg Fiebiger, a German production manager and composer of film music. It had an alternative ending lighter than the original and the characters were renamed again; Count Orlok's name was changed to Prince Wolkoff, Knock became Karsten, Hutter and Ellen became Kundberg and Margitta, and Annie was changed to Maria.[1] This version, of which Murnau was unaware, contained many scenes filmed by Murnau but not previously released. It also contained additional footage not filmed by Murnau but by a cameraman, Günther Krampf, under the direction of Waldemar Roger (also known as Waldemar Ronger),[28] supposedly also a film editor and lab chemist. The name of director F. W. Murnau is no longer mentioned in the credits. This version, lasting approximately 80 minutes, was presented on 5 June 1981 at the Cinémathèque Française.[29]

Reception and legacy

Nosferatu brought Murnau into the public eye, especially when his film Der brennende Acker (The Burning Soil) was released a few days later. The press reported extensively on Nosferatu and its premiere. With the laudatory votes, there was also occasional criticism that the technical perfection and clarity of the images did not fit the horror theme. The Filmkurier of 6 March 1922 said that the vampire appeared too corporeal and brightly lit to appear genuinely scary. Hans Wollenberg described the film in photo-Stage No. 11 of 11 March 1922 as a "sensation" and praised Murnau's nature shots as "mood-creating elements."[30] In the Vossische Zeitung of 7 March 1922, Nosferatu was praised for its visual style.[31]

Nosferatu was also the first film to show a vampire dying from exposure to sunlight. Previous vampire novels such as Dracula had shown them being uncomfortable with sunlight, but not undeath-threateningly so.[32]

The film has received overwhelmingly positive reviews. On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 97% based on 63 reviews, with an average rating of 9.05/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "One of the silent era's most influential masterpieces, Nosferatu's eerie, gothic feel—and a chilling performance from Max Schreck as the vampire—set the template for the horror films that followed."[33] In 1995, the Vatican included Nosferatu on a list of 45 important films that people should watch.[34] It was ranked twenty-first in Empire magazine's "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema" in 2010.[35]

In 1997, critic Roger Ebert added Nosferatu to his list of The Great Movies, writing:

Here is the story of Dracula before it was buried alive in clichés, jokes, TV skits, cartoons and more than 30 other films. The film is in awe of its material. It seems to really believe in vampires. ...Is Murnau's Nosferatu scary in the modern sense? Not for me. I admire it more for its artistry and ideas, its atmosphere and images, than for its ability to manipulate my emotions like a skillful modern horror film. It knows none of the later tricks of the trade, like sudden threats that pop in from the side of the screen. But Nosferatu remains effective: It doesn't scare us, but it haunts us.[36]

In 1993, the 15th episode of the Nickelodeon series Are You Afraid of the Dark? featured a "special" screening of Nosferatu. After the screening, Count Orlok emerges from the screen into the real world and begins stalking victims in the theater.

The 2000 film Shadow of the Vampire is a fictionalized take on the making of Nosferatu.[1]

In 2022 an exhibition Phantoms of the Night. 100 Years of "Nosferatu" opens in Berlin.[37]

The short movie F.W.M. Symphony released in late 2022 is a homage to Nosferatu, and also depicts the theft of Murnau's skull from his family tomb in 2015.[38]

Home video and copyright status

Nosferatu only entered the public domain worldwide by the end of 2019. Despite this, the film had already been subject to widespread circulation via a sped-up, unrestored black and white bootleg copy.[39] Beginning in 1981, the film has had various different official restorations, several of which have been issued on home video in the U.S., Europe and Australia. These versions, which are all tinted, speed-corrected and have specially recorded scores, are separately copyrighted with respect to new copyrightable elements.[1] The most recent restoration, completed in 2005/2006, has been released on DVD and Blu-ray throughout the world, and features a reconstruction of Hans Erdmann's original score by Berndt Heller.[40]

Remakes

A 1979 remake by director Werner Herzog, Nosferatu the Vampyre, starred Klaus Kinski (as Count Dracula, not Count Orlok).[41]

A remake by director David Lee Fisher was in development after being successfully funded on Kickstarter on 3 December 2014.[42] On 13 April 2016, it was reported that Doug Jones had been cast as Count Orlok in the film and that filming had begun. The film would use green screen to insert colorized backgrounds from the original film atop live-action, a process Fisher previously used for his remake The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (2005).[43][1] As of 2023, this version remains unreleased, with the last update coming from Jones in 2020.[44]

In July 2015, another remake was announced with Robert Eggers writing and directing. The film was intended to be produced by Jay Van Hoy and Lars Knudsen for Studio 8.[45] In November 2016, Eggers expressed surprise that the Nosferatu remake was going to be his second film, saying "It feels ugly and blasphemous and egomaniacal and disgusting for a filmmaker in my place to do Nosferatu next. I was really planning on waiting a while, but that's how fate shook out."[46] In 2017, it was announced that Anya Taylor-Joy would be featured in the film in an unknown role.[47] However, in a 2019 interview, Eggers claimed that he was unsure as to whether the film would still be made, saying "...But also, I don't know, maybe Nosferatu doesn't need to be made again, even though I've spent so much time on that."[48] It was reported in September 2022 that Eggers' remake would be distributed by Focus Features, with Bill Skarsgård set to star as Orlok and Lily-Rose Depp as Ellen Hutter.[49] The film wrapped principal photography on May 19, 2023.[50]

References

- "Nosferatu: History and Home Video Guide". Brenton Film. 18 November 2015.

- "Nosferatu: History and Home Video Guide, Part 2: 1920s Screenings". Brenton Film. 30 November 2016.

- "All copies of the cult classic "Nosferatu" were ordered to be destroyed". 5 April 2017.

- Kalat, David (2013). Nosferatu (Blu-ray audio commentary to the film). Eureka Entertainment.

- "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema". Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- "What's the Big Deal?: Nosferatu (1922) (archived October 13, 2011)". Archived from the original on 13 October 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- Klinowski, Jacek; Garbicz, Adam (2012). Feature Cinema in the 20th Century: Volume One: 1913–1950: a Comprehensive Guide. Planet RGB Limited. p. 1920. ISBN 9781624075643. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- Giesen 2019 page 109

- Giesen 2019 page 108

- Giesen 2019 pages 108–109

- Magistrale 2005 page 25–26

- Magistrale 2005 page 25

- Joslin 2017 page 15

- Jackson 2013 page 20

- Elsaesser, Thomas (February 2001). "Six Degrees Of Nosferatu". Sight and Sound. ISSN 0037-4806. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- Mückenberger, Christiane (1993), "Nosferatu", in Dahlke, Günther; Karl, Günter (eds.), Deutsche Spielfilme von den Anfängen bis 1933 (in German), Berlin: Henschel Verlag, p. 71, ISBN 3-89487-009-5

- Eisner 1967 page 27

- Votruba, Martin. "Nosferatu (1922) Slovak Locations". Slovak Studies Program. University of Pittsburgh.

- Prinzler page 222: Luciano Berriatúa and Camille Blot in section: Zur Überlieferung der Filme. Then it was usual to use at least two cameras in parallel to maximize the number of copies for distribution. One negative would serve for local use and another for foreign distribution.

- Eisner 1967 page 28 Since vampires dying in daylight appears neither in Stoker's work nor in Galeen's script, this concept has been solely attributed to Murnau.

- Michael Koller (July 2000), "Nosferatu", Issue 8, July–Aug 2000, senses of cinema, archived from the original on 5 July 2009, retrieved 23 April 2009

- Grafe page 117

- Randall D. Larson (1996). "An Interview with James Bernard" Soundtrack Magazine. Vol 15, No 58, cited in Randall D. Larson (2008). "James Bernard's Nosferatu". Retrieved on 31 October 2015.

- "100 Years of 'Nosferatu,' the Vampire Movie That Won't Die". The New York Times. 24 March 2022.

- Ashbury, Roy (5 November 2001), Nosferatu (1st ed.), Pearson Education, p. 41

- Eisner page 60

- "ADVERTENTIEN". Haagsche Courant. 16 February 1922. p. 3.

- "Waldemar Ronger". www.filmportal.de. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- Reid, Brent (2 December 2016). "Nosferatu: Chronicles from the Vaults". brentonfilm.com. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- Prinzler, Hans Helmut, ed. (2003). Murnau – Ein Melancholiker des Films. Berlin: Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek. Bertz. p. 129. ISBN 3-929470-25-X.

- "Nosferatu". www.filmhistoriker.de (in German). Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

Murnau, sein Bildlenker, stellt die Bildchen, sorglich durchgearbeitet, in sich abgeschlossen. Das Schloß des Entsetzens, das Haus des Nosferatu sind packende Leistungen. Ein Motiv-Museum.

- Scivally, Bruce (1 September 2015). Dracula FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the Count from Transylvania. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-61713-636-8.

- "Nosferatu, a Symphony of Horror (Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens) (Nosferatu the Vampire) (1922)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- "The Vatican Film List". Decent Films. SDQ reviews. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema: 21 Nosferatu". Empire.

- Ebert, Roger (28 September 1997). "Nosferatu Movie Review & Film Summary (1922)". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- "Phantome der Nacht. 100 Jahre Nosferatu". Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- "F.W.M. – Symphonie". fwms.film. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Reid, Brent (7 June 2018). "Nosferatu: History and Home Video Guide, Part 3". Brenton Film. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- Reid, Brent (7 June 2018). "Nosferatu: History and Home Video Guide, Part 6". Brenton Film. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- Erickson, Hal. "Nosferatu the Vampyre". Allrovi. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- "Thank you from Doug & David!". Kickstarter. 6 December 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- "Doug Jones to Star in 'Nosferatu' Remake". Variety. 13 April 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- "Doug Jones' Twitter". 11 March 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- Fleming, Mike Jr. (28 July 2015). "Studio 8 Sets Nosferatu Remake; The Witch's Robert Eggers to Write & Direct". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- O'Falt, Chris (11 November 2016). "Filmmaker Toolkit Podcast: Witch Director Robert Eggers' Lifelong Obsession with Nosferatu and His Plans for a Remake (Episode 13)". Indiewire. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "'Split' Star Anya Taylor-Joy Reteams With 'Witch' Director on 'Nosferatu' Remake (EXCLUSIVE)". 14 August 2017.

- "Robert Eggers on Status of Nosferatu, Prepping Next Film". 15 October 2019.

- Kroll, Justin (30 September 2022). "Bill Skarsgard & Lily-Rose Depp To Star In 'Nosferatu', Robert Eggers' Follow-Up To 'Northman' For Focus". Deadline. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- Squires, John (30 May 2023). "Filming on the Robert Eggers 'Nosferatu' Remake Has Reportedly Wrapped in Prague". Bloody Disgusting!. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

Bibliography

- Brill, Olaf, Film Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens (GER 1922) (in German), archived from the original on 19 August 2009, retrieved 11 June 2009 (1921-1922 reports and reviews)

- Eisner, Lotte H. (1967). Murnau. Der Klassiker des deutschen Films (in German). Velber/Hannover: Friedrich Verlag.

- Eisner, Lotte H. (1980). Hoffmann, Hilmar; Schobert, Walter (eds.). Die dämonische Leinwand (in German). Frankfurt am Main. ISBN 3-596-23660-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Giesen, Rolf (2019). The Nosferatu Story: The Seminal Horror Film, Its Predecessors and Its Enduring Legacy. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1476672984.

- Grafe, Frieda (2003). Patalas, Enno (ed.). Licht aus Berlin: Lang/Lubitsch/Murnau (in German). Berlin: Verlag Brinkmann & Bose. ISBN 978-3922660811.

- Jackson, Kevin (2013). Nosferatu eine Symphonie des Grauens. British Film Institute. ISBN 978-1844576500.

- Joslin, Lyndon W. (2017). Count Dracula Goes to the Movies: Stoker's Novel Adapted (3rd ed.). McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1476669878.

- Magistrale, Tony (2005). Abject Terrors: Surveying the Modern and Postmodern Horror Film. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0820470566.

- Meßlinger, Karin; Thomas, Vera (2003). Prinzler, Hans Helmut (ed.). Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau: ein Melancholiker des Films (in German). Berlin: Bertz Verlag GbR. ISBN 3-929470-25-X.

External links

- Nosferatu at IMDb

- Nosferatu at AllMovie

- Nosferatu at Rotten Tomatoes

- Nosferatu at the TCM Movie Database

- Nosferatu: History and Home Video Guide at Brenton Film

- Nosferatu is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive