Margaret Oliphant

Margaret Oliphant Wilson Oliphant (born Margaret Oliphant Wilson; 4 April 1828 – 20 June 1897[1]) was a Scottish novelist and historical writer, who usually wrote as Mrs. Oliphant. Her fictional works cover "domestic realism, the historical novel and tales of the supernatural".[2]

Margaret Oliphant | |

|---|---|

An 1881 sketch | |

| Born | Margaret Oliphant Wilson 4 April 1828 Wallyford, Scotland |

| Died | 20 June 1897 (aged 69) Wimbledon, London, England |

| Genre | Romance |

| Signature | |

Life

Margaret was born at Wallyford, near Musselburgh, East Lothian, as the only daughter and youngest surviving child of Margaret Oliphant (c. 1789 – 17 September 1854) and Francis W. Wilson (c. 1788–1858), a clerk.[3][4] She spent her childhood at Lasswade, Glasgow and Liverpool. A street, Oliphant Gardens in Wallyford, is named after her. As a girl, she continually experimented with writing. She had her first novel published, Passages in the Life of Mrs. Margaret Maitland, in 1849. This dealt with the relatively successful Scottish Free Church movement, with which her parents sympathised. Next came Caleb Field in 1851, the year she met the publisher William Blackwood in Edinburgh and was invited to contribute to Blackwood's Magazine – a tie that continued for her lifetime and covered over 100 articles, including a critique of the character of Arthur Dimmesdale in Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter.

In May 1852, Margaret married her cousin, Frank Wilson Oliphant, at Birkenhead and settled at Harrington Square, now in Camden, London. Her husband was an artist working mainly in stained glass. Three of their six children died in infancy.[5] Her husband developed tuberculosis and for his health they moved in January 1859 to Florence and then to Rome, where he died. This left Oliphant in need of an income. She returned to England and took up literature to support her three surviving children.[6]

She had become a popular writer by then and worked notably hard to sustain her position. Unfortunately, her home life was full of sorrow and disappointment. In January 1864 her one remaining daughter Maggie died in Rome and was buried in her father's grave. Her brother, who had emigrated to Canada, was shortly afterwards involved in financial ruin. Oliphant offered a home to him and his children, adding their support to already heavy responsibilities.[6]

In 1866 she settled at Windsor to be near her sons, who were attending Eton. That year, her second cousin, Annie Louisa Walker, came to live with her as a companion-housekeeper.[8] Windsor was her home for the rest of her life. Over more than 30 years she pursued a varied literary career, but personal troubles continued. Her ambitions for her sons remained unfulfilled. Cyril Francis, the elder, died in 1890, leaving a Life of Alfred de Musset, incorporated in his mother's Foreign Classics for English Readers.[9] The younger, Francis (whom she called "Cecco"), collaborated with her in the Victorian Age of English Literature and won a position at the British Museum, but was rejected by Sir Andrew Clark, a famous physician. He died in 1894. With the last of her children lost to her, she had little further interest in life. Her health steadily declined and she died at Wimbledon on 20 June 1897.[6][1][10] She was buried in Eton beside her sons.[7] She left a personal estate worth a gross £4,932 and a net value £804.[1]

In the 1880s Oliphant acted as literary mentor of the Irish novelist Emily Lawless. During that time, Oliphant wrote several works of supernatural fiction, including a long ghost story A Beleaguered City (1880) and several short tales, including "The Open Door" and "Old Lady Mary".[11] Oliphant also wrote historical fiction. Magdalen Hepburn (1854) is set during the Scottish Reformation, and features Mary, Queen of Scots and John Knox as characters.[12]

Gallery

Portrait of Oliphant, by Frederick Augustus Sandys, chalk, 1881.

Portrait of Oliphant, by Frederick Augustus Sandys, chalk, 1881. Albumen carte-de-visite, by Thomas Rodger, ca. 1860s.

Albumen carte-de-visite, by Thomas Rodger, ca. 1860s. Margaret Oliphant, by Janet Mary Oliphant, 1895.

Margaret Oliphant, by Janet Mary Oliphant, 1895. Margaret Oliphant, by Hills & Saunders.

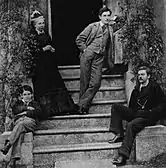

Margaret Oliphant, by Hills & Saunders. Margaret Oliphant and her family in Windsor, 1874.

Margaret Oliphant and her family in Windsor, 1874.

Works

Oliphant wrote more than 120 works, including novels, books of travel and description, histories, and volumes of literary criticism.[6]

Novels

- Margaret Maitland (1849)

- Merkland (1850)

- Caleb Field (1851)

- John Drayton (1851)

- Adam Graeme (1852)

- The Melvilles (1852)

- Katie Stewart (1852)

- Harry Muir (1853)

- Ailieford (1853)

- The Quiet Heart (1854)

- Magdalen Hepburn (1854)

- Zaidee (1855)

- Lilliesleaf (1855)

- Christian Melville (1855)

- The Athelings (1857)

- The Days of My Life (1857)

- Orphans (1858)

- The Laird of Norlaw (1858)

- Agnes Hopetoun's Schools and Holidays (1859)

- Lucy Crofton (1860)

- The House on the Moor (1861)

- The Last of the Mortimers (1862)

- Heart and Cross (1863)

- The Chronicles of Carlingford in Blackwood's Magazine (1862–1865), republished as:

- The Executor (1861)

- The Rector (1861)

- The Doctor's Family (1861)

- Salem Chapel (1863)

- The Perpetual Curate (1864)

- Miss Marjoribanks (1865–66)

- Phoebe Junior (1876)

- A Son of the Soil (1865)

- Agnes (1866)

- Madonna Mary (1867)

- Brownlows (1868)

- The Minister's Wife (1869)

- The Three Brothers (1870)

- John: A Love Story (1870)

- Squire Arden (1871)

- At his Gates (1872)

- Ombra (1872)

- May (1873)

- Innocent (1873)

- The Story of Valentine and his Brother (1875)

- A Rose in June (1874)

- For Love and Life (1874)

- Whiteladies (1875)

- An Odd Couple (1875)

- The Curate in Charge (1876)

- Carità (1877)

- Young Musgrave (1877)

- Mrs. Arthur (1877)

- The Primrose Path (1878)

- Within the Precincts (1879)

- The Fugitives (1879)

- A Beleaguered City (1879)

- The Greatest Heiress in England (1880)

- He That Will Not When He May (1880)

- In Trust (1881)

- Harry Joscelyn (1881)

- Lady Jane (1882)

- A Little Pilgrim in the Unseen (1882)

- The Lady Lindores (1883)

- Sir Tom (1883)

- Hester (1883)

- It Was a Lover and his Lass (1883)

- The Lady's Walk (1883)

- The Wizard's Son (1884)

- Madam (1884)

- The Prodigals and their Inheritance (1885)

- Oliver's Bride (1885)

- A Country Gentleman and his Family (1886)

- A House Divided Against Itself (1886)

- Effie Ogilvie (1886)

- A Poor Gentleman (1886)

- The Son of his Father (1886)

- Joyce (1888)

- Cousin Mary (1888)

- The Land of Darkness (1888)

- Lady Car (1889)

- Kirsteen (1890)

- The Mystery of Mrs. Blencarrow (1890)

- Sons and Daughters (1890)

- The Railway Man and his Children (1891)

- The Heir Presumptive and the Heir Apparent (1891)

- The Marriage of Elinor (1891)

- Janet (1891)

- The Story of a Governess (1891)

- The Cuckoo in the Nest (1892)

- Diana Trelawny (1892)

- The Sorceress (1893)

- A House in Bloomsbury (1894)

- Sir Robert's Fortune (1894)

- Who Was Lost and is Found (1894)

- Lady William (1894)

- Two Strangers (1895)

- Old Mr. Tredgold (1895)

- The Unjust Steward (1896)

- The Ways of Life (1897)

Short stories

- Neighbours on the Green (1889)

- A Widow's Tale and Other Stories (1898)

- That Little Cutty (1898)

- "The Open Door." In: Great Ghost Stories (1918)

Selected articles

- "Mary Russel Mitford," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 75, 1854

- "Evelin and Pepys," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 76, 1854

- "The Holy Land," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 76, 1854

- "Mr. Thackeray and his Novels," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 77, 1855

- "Bulwer," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 77, 1855

- "Charles Dickens," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 77, 1855

- "Modern Novelists—Great and Small," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 77, 1855

- "Modern Light Literature: Poetry," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 79, 1856

- "Religion in Common Life," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 79, 1856

- "Sydney Smith," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 79, 1856

- "The Laws Concerning Women," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 79, 1856

- "The Art of Caviling," Backwood's Magazine, Vol. 80, 1856

- "Béranger," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 83, 1858

- "The Condition of Women," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 83, 1858

- "The Missionary Explorer," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 83, 1858

- "Religious Memoirs," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 83, 1858

- "Social Science," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 88, 1860

- "Scotland and her Accusers," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 90, 1861

- "Girolamo Savonarola," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 93, 1863

- "The Life of Jesus," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 96, 1864

- "Giacomo Leopardi," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 98, 1865

- "The Great Unrepresented," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 100, 1866

- "Mill on the Subjection of Women," The Edinburgh Review, Vol. 130, 1869

- "The Opium-Eater," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 122, 1877

- "Russian and Nihilism in the Novels of I. Tourgeniéf," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 127, 1880

- "School and College," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 128, 1880

- "The Grievances of Women," Fraser's Magazine, New Series, Vol. 21, 1880

- "Mrs. Carlyle," The Contemporary Review, Vol. 43, May 1883

- "The Ethics of Biography," The Contemporary Review, July 1883

- "Victor Hugo," The Contemporary Review, Vol. 48, July/December 1885

- "A Venetian Dynasty," The Contemporary Review, Vol. 50, August 1886

- "Laurence Oliphant," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 145, 1889

- "Tennyson," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 152, 1892

- "Addison, the Humorist," Century Magazine, Vol. 48, 1894

- "The Anti-Marriage League," Blackwood's Magazine, Vol. 159, 1896

Biographies

Oliphant's biographies of Edward Irving (1862) and her cousin Laurence Oliphant (1892), together with her life of Sheridan in the English Men of Letters series (1883), show vivacity and a sympathetic touch. She also wrote lives of Francis of Assisi (1871), the French historian Count de Montalembert (1872),[13][14] Dante (1877),[9] Miguel de Cervantes (1880),[9] and the Scottish theologian John Tulloch (1888).

Historical and critical works

- Historical Sketches of the Reign of George II (1869) (See George II.)

- The Makers of Florence (1876)

- A Literary History of England from 1760 to 1825 (1882)

- The Makers of Venice (1887)

- Royal Edinburgh (1890)

- Jerusalem, the Holy City, Its History and Hope (1891)

- The Makers of Modern Rome (1895)

- William Blackwood and his Sons (1897)[15]

- "The Sisters Brontë." In: Women Novelists of Queen Victoria's Reign (1897)

At the time of her death, Oliphant was still working on Annals of a Publishing House, a record of the progress and achievement of the firm of Blackwood, with which she had been so long connected. Her Autobiography and Letters, which present a touching picture of her domestic anxieties, appeared in 1899. Only parts were written with a wider audience in mind: she had originally intended the Autobiography for her son, but he died before she had finished it.[16]

Critical reception

Opinions on Oliphant's work are split, with some critics seeing her as a "domestic novelist", while others recognize her work as influential and important to the Victorian literature canon. Critical reception from Oliphant's contemporaries is divided as well. Among those who were not in favour of Oliphant was John Skelton, who took the view that Oliphant wrote too much and too fast.[17] Writing a Blackwood's article called "A Little Chat About Mrs. Oliphant", he asked, "Had Mrs. Oliphant concentrated her powers, what might she not have done? We might have had another Charlotte Brontë or another George Eliot."[18] Not all of the contemporary reception was negative, though. M. R. James admired Oliphant's supernatural fiction, concluding that "the religious ghost story, as it may be called, was never done better than by Mrs. Oliphant in "The Open Door" and A Beleaguered City".[19] Mary Butts lauded Oliphant's ghost story "The Library Window", describing it as "one masterpiece of sober loveliness".[20] Principal John Tulloch praised her "large powers, spiritual insight, and purity of thought, and subtle discrimination of many of the best aspects of our social life and character".[21]

More modern critics of Oliphant's work include Virginia Woolf, who asked in Three Guineas whether Oliphant's autobiography does not lead the reader "to deplore the fact that Mrs. Oliphant sold her brain, her very admirable brain, prostituted her culture and enslaved her intellectual liberty in order that she might earn her living and educate her children."[22] However, even modern critics are divided on Oliphant's work. Authors Gilbert and Gubar did not include Oliphant in their "Great tradition" of women's writing because she did not question or challenge the patriarchy at the time of her life and writing.[17]

Revival of interest

Interest in Mrs Oliphant's work declined in the 20th century. In the mid-1980s, a small-scale revival was led by the publishers Alan Sutton[23] and Virago Press, centred on the Carlingford series and some similarities of subject-matter with the work of Anthony Trollope.[24]

Penguin Books in 1999 published an edition of Miss Marjoribanks (1866).[25] Hester (1873) was reissued in 2003 by Oxford World's Classics.[26] In 2007–2009, the Gloucester publisher Dodo Press reprinted half a dozen of Oliphant's works. In 2010, both the British Library and Persephone Books reissued The Mystery of Mrs. Blencarrow (1890), in the latter case with the novella Queen Eleanor and Fair Rosamund (1886),[27] and the Association for Scottish Literary Studies produced a new edition of the novel Kirsteen (1890).[28]

BBC Radio 4 broadcast four-hour dramatisations of Miss Marjoribanks in August/September 1992 and Phoebe Junior in May 1995. A 70-minute adaptation of Hester was broadcast on Radio 4 in January 2014.[29]

Russell Hoban alludes to Oliphant's fiction in his 2003 novel Her Name Was Lola.[30]

References

{{columns-list|colwidth=30em|

- "Wills.-Mrs. Margaret Oliphant Wilson". News. The Times. No. 35354. London. 6 November 1897. p. 14. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Margaret Oliphant, Miss Majoribanks, ed. Elisabeth Jay. New York: Penguin Classics, 1999, p. vii.

- Jay, Elisabeth (23 September 2004). "Oliphant, Margaret Oliphant Wilson (1828–1897), novelist and biographer". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1 (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20712. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Deaths". The Times. No. 21850. London. 19 September 1854. p. 1. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- According to Elizabeth Jay, in the introduction of Margaret Oliphant's Autobiography (published in 2002), p. 9, one of these children died aged one day, another, Stephen Thomas, at nine weeks, and Marjorie, the other daughter, at about eight months. The surviving children were Maggie (died in 1864), Cyril Francis, "Tiddy" (died in 1890) and Francis Romano, "Cecco" (died in 1894). However, The Victorian Web mentions seven children. See also Elisabeth Jay: Oliphant, Margaret Oliphant... In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: OUP, 2004). Retrieved 14 November 2010. Subscription required. for the countless dependents she supported through much of her life.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Oliphant, Margaret Oliphant". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 83–84.

- ODNB

- Elizabeth Jay, ed. (2002). The autobiography of Margaret Oliphant. ississauga, Canada: Broadview Press Ltd. ISBN 1-55111-276-0.

- Foreign Classics for English Readers (William Blackwood & Sons) - Book Series List, publishinghistory.com. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- "Death of Mrs. Oliphant: Cancer Ends the Career of the Famous English Novelist and Historian," The New York Times, 27 June 1897.

- Mike Ashley, Who's Who in Horror and Fantasy Fiction. Elm Tree Books, 1977. ISBN 0-241-89528-6, p. 142.

- William Russell Aitken, Scottish literature in English and Scots: a guide to information sources. Gale Research Co., 1982 ISBN 9780810312494, p. 146.

- Memoir of Count de Montalembert by Mrs. Oliphant. Collection of British authors. Tauchnitz ed.,vol. 1284. B. Touchnitz. 1872.

- Simcox, G. A. (1 November 1872). "Review of Memoir of Count de Montalembert by Mrs. Oliphant". The Academy. 3 (59): 401–403.

- "Review of Annals of a Publishing House. William Blackwood and his Sons. Their Magazine and Friends. by Mrs. Oliphant". The Quarterly Review. 187: 234–258. January 1898.

- George P. Landow (1988). "The Problematic Relationship of Autobiographer to Audience". Victorianweb.org. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- The new nineteenth century : feminist readings of underread Victorian fiction. Harman, Barbara Leah., Meyer, Susan, 1960-. New York: Garland Pub. 1996. ISBN 081531292X. OCLC 33948483.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Skelton, John. "A Little Chat About Mrs. Oliphant". Blackwood's Magazine. 133: 73–91.

- M. R. James,"Some Remarks on Ghost Stories", in The Bookman, December 1929. Reprinted in James, Collected Ghost Stories, edited by Darryl Jones. Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2011. ISBN 9780199568840 (p. 414)

- Mary Butts, "Ghosties and Ghoulies: The Uses of the Supernatural in English Fiction" (1933). In Ashe of Rings and Other Writings. Kingston, NY: McPherson & Co., ISBN 0929701534 (p.358)

- John Tulloch, Movements of Religious Thought in Britain during the Nineteenth Century: St. Giles' Lectures, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1893, Dedication. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- Woolf, Virginia (1966). Three Guineas. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovinch.

- The Curate in Charge (1875), reissued in 1985. ISBN 0-86299-327-X.

- See, for example, the blurb and introduction (p. xiv) to the 1987 Virago paperback edition of The Perpetual Curate. ISBN 0-86068-786-4.

- ISBN 0-14-043630-8.

- ISBN 0-19-280411-1.

- Persephone site: Retrieved 30 October 2010. Archived 29 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ASLS site: Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "BBC Radio 4 Extra - Hester - Omnibus". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- "He [Hoban] also references Gothic writers who have influenced him, such as Margaret Oliphant and Oliver Onions." Review of Her Name Was Lola by Russell Hoban. The Times, 8 November 2003, (p.14).

Further reading

- D'Albertis, Deirdre (1997). "The Domestic Drone: Margaret Oliphant and a Political History of the Novel," SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900, Vol. 37, No. 4, pp. 805–829.

- Clarke, John Stock. Margaret Oliphant: A Bibliography of Secondary Sources 1848–2005.

- Clarke, John Stock. Margaret Oliphant: Non-Fiction Bibliography.

- Clarke, John Stock Margaret Oliphant: Fiction Bibliography.

- Colby, Vineta and Robert Colby (1966). The Equivocal Virtue: Mrs. Oliphant and the Victorian Literary Market Place. Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books.

- Garnett, Richard (1901). "Oliphant, Margaret Oliphant." In: Dictionary of National Biography, Supplement, Vol. III. New York: The Macmillan Company, pp. 230–234.

- Halsey, Francis W. (1899). "Mrs. Oliphant," The Book Buyer, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 111–113.

- Hubbard, Tom (2011), "Margaret Oliphant's Beleagured City", in Hubbard, Tom (2022), Invitation to the Voyage, Scotland, Europe and Literature, Rymour, pp. 53 – 57, ISBN 9-781739-596002

- Jay, Elisabeth (1994). Mrs Oliphant: "A Fiction to Herself" – A Literary Life. Oxford University Press.

- Jay, Elisabeth. "Oliphant, Margaret Oliphant Wilson (1828–1897)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20712. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Kämper, Birgit (2001). Margaret Oliphant's Carlingford Series: An Original Contribution to the Debate on Religion, Class, and Gender in the 1860s and '70s. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Michie, Elsie B. (2001). "Buying Brains: Trollope, Oliphant, and Vulgar Victorian Commerce," Victorian Studies, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp. 77–97.

- "Mrs. Oliphant and her Rivals," The Scottish Review, Vol. 30, 1897, pp. 282–300.

- "Mrs. Oliphant," The Living Age, Vol. 214, 1897, pp. 403–407.

- "Mrs. Oliphant as a Novelist," The Living Age, Vol. 215, 1897, pp. 74–85.

- "Mrs. Oliphant's Autobiography," The Scottish Review, Vol. 34, 1899, pp. 124–138.

- "Mrs. Oliphant's Autobiography," The Quarterly Review, Vol. 190, 1899, pp. 255–267.

- Nicoll, W. Robertson (1897). "Mrs. Oliphant," The Bookman, Vol. 5, pp. 484–486.

- Onslow, Barbara (1998). "'Humble Comments for the Ignorant': Margaret Oliphant's Criticism of Art and Society," Victorian Periodicals Review, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 55–74.

- Preston, Harriet Waters (1885). "Mrs. Oliphant," The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 55, pp. 733–744.

- Preston, Harriet Waters (1897). "Mrs. Oliphant," The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 80, pp. 424–427.

- Preston, Harriet Waters (1897). "Margaret Oliphant Wilson Oliphant." In: Library of the World's Best Literature, Vol. XIX. New York: R.S. Peale & J.A. Hill.

- Preston, Harriet Waters (1899). "The Autobiography of Mrs. Oliphant," The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. 84, pp. 567–573.

- Rubik, Margarete (1994). The Novels of Mrs Oliphant, A Subversive View of Traditional Themes. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Sime, (Jessie) Georgina, and Frank (Carr) Nicholson (1952). "Recollections of Mrs. Oliphant." In: Brave Spirits. London: privately printed, distributed by Simpkin Marshall & Co., pp. 25–55.

- "The Life and Writings of Mrs. Oliphant," The Edinburgh Review, Vol. 190, 1899, pp. 26–47.

- Trela, D.J. (1995). Margaret Oliphant: Critical Essays on a Gentle Subversive. Selinsgrove: Susquehanna University Press.

- Trela, D.J. (1996). "Margaret Oliphant, James Anthony Froude and the Carlyles' Reputations: Defending the Dead," Victorian Periodicals Review, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 199–215.

- Walker, Hugh (1921). The Literature of the Victorian Era. Cambridge University Press.

- Williams, Merryn (1986). Margaret Oliphant: A Critical Biography. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- "Works by Mrs. Oliphant," The British Quarterly Review, Vol. 49, 1869, pp. 301–329.

External links

| Library resources about Margaret Oliphant |

| By Margaret Oliphant |

|---|

- Works by Margaret Oliphant in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- The Margaret Oliphant Fiction Collection – all novels and stories with summaries, pictures, links, series, themes.

- Works by Margaret Oliphant at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Margaret Oliphant at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Margaret Oliphant at Internet Archive

- Works by Margaret Oliphant at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Margaret Oliphant at The Victorian Web

- Works at Open Library

- Basketful of Fragments: Krystyna Weinstein's 'fictional autobiography' of Margaret Oliphant

- "Archival material relating to Margaret Oliphant". UK National Archives.