Mumun pottery period

The Mumun pottery period is an archaeological era in Korean prehistory that dates to approximately 1500-300 BC.[1][2][3] This period is named after the Korean name for undecorated or plain cooking and storage vessels that form a large part of the pottery assemblage over the entire length of the period, but especially 850-550 BC.

| Geographical range | Korean peninsula |

|---|---|

| Period | Late Stone Age , Bronze Age |

| Dates | c. 1500 – c. 300 BC |

| Preceded by | Jeulmun pottery period |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 무문토기시대 |

| Hanja | 無文土器時代 |

| Revised Romanization | Mumun togi sidae |

| McCune–Reischauer | Mumun t'ogi sidae |

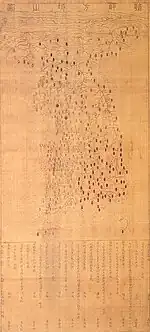

| History of Korea |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Mumun period is known for the origins of intensive agriculture and complex societies in both the Korean Peninsula and the Japanese Archipelago.[2][3][4] This period or parts of it have sometimes been labelled as the "Korean Bronze Age", after Thomsen's 19th century three-age system classification of human prehistory. However, the application of such terminology in the Korean case is misleading since local bronze production did not occur until approximately the late 8th century BC at the earliest, bronze artifacts are rare, and the distribution of bronze is highly regionalized until after 300 BC.[5][6] A boom in the archaeological excavations of Mumun Period sites since the mid-1990s has recently increased collective knowledge about this formative period in the prehistory of East Asia.

The Mumun period is preceded by the Jeulmun Pottery Period (c. 8000-1500 BC). The Jeulmun was a period of hunting, gathering, and small-scale cultivation of plants.[6] The origins of the Mumun Period are not well known, but the megalithic burials, Mumun pottery, and large settlements found in the Liao River Basin and North Korea c. 1800-1500 probably indicate the origins of the Mumun Period of Southern Korea. Slash-and-burn cultivators who used Mumun pottery displaced people using Jeulmun Period subsistence patterns.[7]

Chronology

Early Mumun

The Early (or Formative) Mumun (c. 1500-850 BC) is characterized by shifting cultivation, fishing, hunting, and discrete settlements with rectangular semi-subterranean pit-houses. The social scale of Early Mumun societies was egalitarian in nature, but the latter part of this period is characterized by increasing intra-settlement competition and perhaps the presence of part-time "big-man" leadership.[8] Early Mumun settlements are relatively concentrated in the river valleys formed by tributaries of the Geum River in West-central Korea. However, one of the largest Early Mumun settlements, Eoeun (Hangeul: 어은), is located in the Middle Nam River valley in South-central Korea. In the latter Early Mumun, large settlements composed of many long-houses such as Baekseok-dong (Hangeul: 백석동) appeared in the area of modern Cheonan City, Chungcheong Nam-do.

Important long-term traditions related to Mumun ceremonial and mortuary systems originated in this sub-period. These traditions include the construction of megalithic burials, the production of red-burnished pottery, and production of polished groundstone daggers.

Middle Mumun

The Middle (or Classic) Mumun (c. 850-550 BC) is characterized by intensive agriculture, as evidenced by the large and expansive dry-field remains (c. 32,500 square metres) recovered at Daepyeong, a sprawling settlement with several multiple ditch enclosures, hundreds of pit-houses, specialized production, and evidence of the presence of incipient elites and social competition.[2][3][9] A number of wet-field features have been excavated in southern Korea, indicating that paddy field rice-farming was also practiced.

Burials dating to the latter part of the Middle Mumun (c. 700-550 BC) contain a few high status mortuary offerings such as bronze artifacts. Bronze production probably began around this time in Southern Korea. Other high status burials contain greenstone (or jade) ornaments.[4][9] A number of megalithic burials with deep shaft interments, substantial 'pavements' of rounded cobblestone, and prestige artifacts such as bronze daggers, jade, and red-burnished vessels were built in the vicinity of the southern coast in the Late Middle Mumun. High status megalithic burials and large raised-floor buildings at the Deokcheon-ni (Hangeul: 덕천리) and Igeum-dong sites in Gyeongsang Nam-do provide further evidence of the growth of social inequality and the existence of polities that were organized in ways that appear to be similar to simple "chiefdoms".[4]

Korean archaeologists sometimes refer to Middle Mumun culture as Songguk-ri Culture (Hanja: 松菊里 文化; Hangeul: 송국리 문화).[1] Co-occurring artifacts and features that are grouped together as Songguk-ri Culture are found in settlement sites in the Hoseo and Honam regions of southeast Korea, but Songguk-ri Culture settlements are also found in western Yeongnam. Excavations have also revealed Songguk-ri settlements in the Ulsan and Gimhae areas. In 2005 archaeologists uncovered Songguk-ri Culture pit-houses at a site deep in the interior of Gangwon Province. The ultimate geographic reach of Songguk-ri Culture appears to have been Jeju Island and western Japan.

Mumun culture is the beginning of a long-term tradition of rice-farming in Korea that links Mumun Culture with the present day, but evidence from the Early and Middle Mumun suggests that, although rice was grown, it was not the dominant crop.[3] During the Mumun people grew millets, barley, wheat, legumes, and continued to hunt and fish.

Late Mumun

The Late (or Post-classic) Mumun (550-300 BC) is characterized by increasing conflict, fortified hilltop settlements, and a concentration of population in the southern coastal area. A Late Mumun occupation was found at the Namsan settlement, located on the top of a hill 100 m above sea level in modern Changwon City, Gyeongsang Nam-do. A shellmidden (shellmound) was found in the vicinity of Namsan, indicating that, in addition to agriculture, shellfish exploitation was part of the Late Mumun subsistence system in some areas. Pit-houses at Namsan were located inside a ring-ditch that is some 4.2 m deep and 10 m in width. Why would such a formidable ring-ditch, so massive in size, have been necessary? One possible answer is intergroup conflict. Archaeologists propose that the Late Mumun was a period of conflict between groups of people.

The number of settlements in the Late Mumun is much lower than in the previous sub-period. This indicates that populations were reorganized and settlement was probably more concentrated in a smaller number of larger settlements. There are a number of reasons why this could have occurred. There are some indications that conflict increased or climatic change led to crop failures.

Notably, according to the traditional Yayoi chronological sequence, Mumun-esque settlements appeared in Northern Kyūshū (Japan) during the Late Mumun. The Mumun period ends when iron appeared in the archaeological record along with pit-houses that had interior composite hearth-ovens reminiscent of the historic period (agungi).

Some scholars suggest that the Mumun pottery period should be extended to c. 0 BC because of the presence of an undecorated ware that was popular between 400 BC and 0 BC called jeomtodae (Korean: 점토대). However, bronze became very important in ceremonial and elite life from 300 BC. Additionally, iron tools are increasingly found in Southern Korea after 300 BC. These factors clearly differentiate the time period 300 BC - 0 from the cultural, technological, and social scale that was present in the Mumun pottery period. The unequal presence of bronze and iron in increased amounts from a few high status graves after 300 BC as sets this time apart from the Mumun pottery period. It is thus that, as a cultural-technical period, the Mumun was finished by approximately 300 BC.

From about 300 BC, bronze objects became the most valued prestige mortuary goods, but iron objects were traded and then produced in the Korean peninsula at that time. The Late Mumun-Early Iron Age Neuk-do Island Shellmidden Site yielded a small number of iron objects, Lelang and Yayoi pottery, and other evidence showing that beginning in the Late Mumun, local societies were drawn into closer economic and political contact with the societies of the Late Zhou Dynasty, Final Jōmon, and Early Yayoi.

Mumun cultural traits

As an archaeological culture, the Mumun is composed of the following elements:

Languages

According to Juha Janhunen and Alexander Vovin, Japonic languages were spoken in parts of the Korean Peninsula before they were replaced by Koreanic speakers.[10][11] According to Whitman and several other researchers, Japonic/proto-Japonic arrived in the Korean peninsula around 1500 BC[12][13] and was brought to the Japanese archipelago by Yayoi wet-rice farmers at some time between 700-300 BC.[14][15] Whitman and Miyamoto associate Japonic as the language family associated with both Mumun and Yayoi cultures.[16][13] Several linguists believe that speakers of Koreanic/proto-Koreanic arrived in the Korean Peninsula at some time after the Japonic/proto-Japonic speakers and coexisted with these peoples (i.e. the descendants of both the Mumun and Yayoi cultures) and possibly assimilated them. Both Koreanic and Japonic had prolonged influence on each other and a later founder effect diminished the internal variety of both language families.[17][18][19]

Subsistence

- Broad-spectrum subsistence was practiced through the Early Mumun. That is to say, evidence excavated from pit-houses and other outdoor household features indicates that hunting, fishing, and foraging was occurring in addition to agriculture.[6]

- stone tools used in agricultural subsistence activities are common and include semi-lunar blades.[4]

- Intensive wet-field agriculture (paddy farming) was in place in the Middle Mumun.[3] However, even the pit-houses of settlements associated with wet-field archaeological features show evidence that people were also engaged to some degree in hunting and fishing.

Settlement

- Large rectangular-shaped pit-houses were used in Early Mumun. These pit-houses had one or more hearths, and pit-houses with up to 6 hearths indicate that such features were the living spaces for multiple generations of the same household.[8]

- Some time after 900 BC, small pit-houses were the norm. The plan-shape of these pit-houses are square, circular and oval. They do not have interior hearths — instead, the central area of the pit-house floor is equipped with a shallow oval 'work-pit'.[1]

- Archaeologists see this change in architecture as a social shift in the household. Namely, the tight and multi-generational unit housed under one roof in the Early Mumun changed fundamentally into households formed of groups of semi-independent nuclear family units in separate pit-houses.[8]

- The average settlement in the Mumun was small, but settlements with as many as several hundred pit-houses emerged in the Middle Mumun.[8]

Economy

- Household production was the basic mode of the Mumun economy, but specialized craft production and a big-man-style redistributive prestige economy emerged in the Middle Mumun.[8]

- Archaeological evidence has documented cases in which it appears that surplus production of crops, stone tools, and pottery occurred in the Middle Mumun.[3][4]

- Artifacts that illustrate regional redistributive systems and exchange include greenstone ornaments, bronze objects, and some kinds of red-burnished pottery.[9]

Mortuary practices

- Megalithic burials, stone-cist burials, and jar burials are found.

- Some burials in the latter part of the Middle Mumun are especially large and required a significant amount of labour to construct. A small number of Middle Mumun burials contain prestige/ceremonial artifacts such as bronze, greenstone, groundstone daggers, and red-burnished ware.[4][9][20]

Gallery

See also

References

- Ahn, Jae-ho (2000). "Hanguk Nonggyeongsahoe-eui Seongnib (The Formation of Agricultural Society in Korea)". Hanguk Kogo-Hakbo (in Korean). 43: 41–66.

- Bale, Martin T. (2001). "Archaeology of Early Agriculture in Korea: An Update on Recent Developments". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 21 (5): 77–84.

- Crawford, Gary W.; Gyoung-Ah Lee (2003). "Agricultural Origins in the Korean Peninsula". Antiquity. 77 (295): 87–95. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00061378. S2CID 163060564.

- Rhee, S. N.; Choi, M. L. (1992). "Emergence of Complex Society in Prehistoric Korea". Journal of World Prehistory. 6: 51–95. doi:10.1007/BF00997585. S2CID 145722584.

- Kim, Seung Og (1996). Political Competition and Social Transformation: The Development of Residence, Residential Ward, and Community in Prehistoric Taegongni of Southwestern Korea. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Lee, June-Jeong (2001). From Shellfish Gathering to Agriculture in Prehistoric Korea: The Chulmun to Mumun Transition. Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison Press.

- Kim, Jangsuk (2003). "Land-use Conflict and the Rate of Transition to Agricultural Economy: A Comparative Study of Southern Scandinavia and Central-western Korea". Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 10 (3): 277–321. doi:10.1023/A:1026087723164. S2CID 144173837.

- Bale, Martin T.; Min-jung Ko (2006). "Craft Production and Social Change in Mumun Period Korea". Asian Perspectives. 45 (2): 159–187. doi:10.1353/asi.2006.0019. hdl:10125/17250. S2CID 55944795.

- Nelson, Sarah M. (1999). "Megalithic Monuments and the Introduction of Rice into Korea". In Gosden, C.; Hather, J. (eds.). The Prehistory of Food: Appetites for Change. London: Routledge. pp. 147–165. ISBN 978-0-415-11765-4.

- Janhunen, Juha (2010). "Reconstructing the Language Map of Prehistorical Northeast Asia". Studia Orientalia (108): 281–304.

... there are strong indications that the neighbouring Baekje state (in the southwest) was predominantly Japonic-speaking until it was linguistically Koreanized.

- Vovin, Alexander (2013). "From Koguryo to Tamna: Slowly riding to the South with speakers of Proto-Korean". Korean Linguistics. 15 (2): 222–240.

- Whitman (2011), p. 157.

- Miyamoto (2016), pp. 69–70.

- Serafim (2008), p. 98.

- Vovin (2017).

- Whitman, John (2011-12-01). "Northeast Asian Linguistic Ecology and the Advent of Rice Agriculture in Korea and Japan". Rice. 4 (3): 149–158. doi:10.1007/s12284-011-9080-0. ISSN 1939-8433.

- Janhunen (2010), p. 294.

- Vovin (2013), pp. 222, 237.

- Unger (2009), p. 87.

- Bale, Martin T. "Excavations of Large-scale Megalithic Burials at Yulha-ri, Gimhae-si, Gyeongsang Nam-do". Korea Institute, Harvard University. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

Further reading

- Nelson, Sarah M. (1993). The Archaeology of Korea. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40443-3.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)