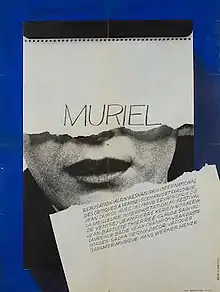

Muriel (film)

Muriel (French: Muriel ou le Temps d'un retour, literally Muriel, or the Time of a Return) is a 1963 French psychological drama film directed by Alain Resnais, and starring Delphine Seyrig, Jean-Pierre Kérien, Jean-Baptiste Thiérrée, and Nita Klein. Its plot follows a middle-aged widow in Boulogne-sur-Mer and her stepson—recently returned from military service in the Algerian War—who are visited by her ex-lover and his new young girlfriend.

| Muriel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Alain Resnais |

| Written by | Jean Cayrol |

| Produced by | Anatole Dauman |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Sacha Vierny |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Hans Werner Henze |

| Distributed by | Argos Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 115 minutes |

| Country | France / Italy |

| Language | French |

It was Resnais's third feature film, following Hiroshima mon amour (1959) and L'Année dernière à Marienbad (1961), and in common with those films it explores the challenge of integrating a remembered or imagined past with the life of the present. It also makes oblique reference to the controversial subject of the Algerian War, which had recently been brought to an end. Muriel was Resnais's second collaboration with Jean Cayrol, who had also written the screenplay of Nuit et brouillard (Night and Fog) (1956).

Plot

Set over a two-week period in 1962, Hélène is a middle-aged widow who runs an antique business from her own apartment in Boulogne-sur-Mer. She resides with her stepson, Bernard, who is haunted by the memory of a girl named Muriel whom he helped torture and murder while doing military service in Algeria. Hélène is visited by a past lover, Alphonse, whom she meets at the local train station one night. She finds he is accompanied by Françoise, a young aspiring actress whom Alphonse introduces as his niece, though she is in truth his young lover. That night, Françoise and Bernard go to walk around town, while Hélène and Alphonse reminisce at the apartment before she is met by her friend, Roland de Smoke, who arrives to escort her to the local casino.

Left alone at Hélène's apartment, Alphonse finds Bernard's journal, in which he writes about Muriel, and how since her death he is "no longer alive." Meanwhile, Françoise and Bernard visit the seaside, where Françoise admits to Bernard that she is in fact Alphonse's girlfriend. Bernard abruptly leaves Françoise to wander the streets alone, and goes to spend the night in a seaside shack he often stays at. When Hélène returns to her apartment, she finds Alphonse angered by her leaving him alone, which stirs up several painful memories where she left him alone. Later, Alphonse admits that, during his military service, he had intended to marry Hélène, but she had refused his invitation to live with him in Algiers. Françoise returns to the apartment after the two have retired for the evening.

At dawn, after tensions have calmed, Hélène and Alphonse spend a pleasant morning together strolling through the city, imagining the life they could have had together. Bernard again encounters Françoise on the street while riding his bicycle, and later briefly speaks with his girlfriend, who informs him she has been admitted to university in Montevideo. Alphonse later strolls along the seaside with Françoise, who tells him that she must leave him when they return to Paris. Hélène and Alphonse have lunch at a cafe, where they encounter Robert, whom Bernard served alongside in the war. She urges Robert to speak with Bernard, whom she worries has become stunted after returning from the war.

Ernest, Alphonse's brother-in-law, arrives in town, demanding he return to his wife—this revelation shocks Hélène. Later, it is revealed that Bernard has murdered Robert. In the midst of the series of troubling events, Alphonse's wife, Simone, arrives at Hélène's empty apartment. She walks from room to room, but finds no one there.

Structure

The story takes place over 15 days in September–October 1962. The published screenplay, which is divided into 5 acts, provides specific dates and times for each scene, but these are not apparent in the film. An extended sequence takes place on the first day (Act 1, a section lasting about 45 minutes: the introductions of Alphonse and his 'niece' Françoise to Hélène and Bernard, their first meal together, and then their separate evening pursuits). Another long sequence takes place on the last day (Act 5: the Sunday lunch and its revelations, and the scattering of the principal characters in their different directions). The intervening days (Acts 2–4) are represented in a series of fragmented scenes, which are chronological but seldom consecutive.[1]

Cast

- Delphine Seyrig, as Hélène Aughain, a widowed antique dealer, about 40 years old, who retains obsessive memories of her love affair with Alphonse when she was 16, and the unexplained manner of their separation in 1939.

- Jean-Pierre Kérien, as Alphonse Noyard, Hélène's sometime lover, who says he has spent many of the intervening years in Algeria running a bar.

- Nita Klein, as Françoise, an aspiring young actress having an affair with the much older Alphonse, and biding her time before leaving him.

- Jean-Baptiste Thierrée, as Bernard, Hélène's stepson, recently returned from doing his military service in Algeria where his role in the torture of a girl called Muriel has left him with traumatic memories.

- Martine Vatel, as Marie-Do, the intermittent girl-friend of Bernard who is ready to set off for a new life in South America.

- Claude Sainval, as Roland de Smoke, a Boulogne property-developer and amorous friend of Hélène.

- Laurence Badie, as Claudie, a friend of Hélène with whom she shares a taste for gambling.

- Jean Champion, as Ernest, the brother-in-law of Alphonse.

- Philippe Laudenbach, as Robert, a fellow-soldier with Bernard in Algeria, now an active member of the OAS.

- Françoise Bertin, as Simone

- Jean Dasté, as the man with a goat, who has returned from Australia.

Production

Development

Alain Resnais and Jean Cayrol first discussed the project of Muriel in 1959. They developed the script while Resnais was working on L'Année dernière à Marienbad as well as on two other (uncompleted) projects relating to the then contentious topic of the war in Algeria.[2] Cayrol, though primarily a poet and novelist, was himself interested in film-making and editing, and he produced a screenplay for Muriel in which nearly all of the complex editing sequences were outlined.[3]: 74

Filming

Filming took place during 12 or 13 weeks between November 1962 and January 1963, the longest shooting time of any of Resnais's films. Location shooting was done in Boulogne-sur-Mer, which is almost another character in the film, a town whose centre has seen rapid rebuilding after extensive war damage and which is presented as both ancient and modern, uncertainly balanced between its past and future.[4]: 109 The scenes in Hélène's apartment where most of the action takes place were filmed on a set at Studios Dumont in Épinay, but Resnais asked the designer Jacques Saulnier to reconstruct exactly a real apartment which he had seen in Boulogne, even down to the colour of the woodwork.[3]: 90 The décor of the apartment is modern but, because of Hélène's business as an antique dealer, it is full of furniture of different styles and periods which continually change through the film.[4]: 109 Resnais explained his intentions: "We used everything that could give this impression of incompleteness, of unease. ...The challenge of the film was to film in colour, that was essential, never to move the camera position, to film a week behind the [time of the] scenario, to invent nothing, and to do nothing to make it prettier". There were around 800 shots in the film instead of the usual 450; the many static camera set-ups were time-consuming; and it was only in the final shot of the film that the camera moved.[5]

Music for the film was written by Hans Werner Henze who picked up the visual principle of multiple fixed camera shots by adopting a musical style which mirrored the fragmentation of the film structure.[6]: 258 A series of verses, by Cayrol, are sung throughout the film (by Rita Streich); the relative lack of clarity of the words on the soundtrack was attributed by Resnais to the effect of having a German composer (who at the time did not speak French) setting French words.[6]: 274 The full words of the verses are included in the published screenplay of the film.[1]

The song "Déja", with words about the passing of time, which is sung unaccompanied by the character of Ernest near the end of the film, was written for a musical review in 1928 by Paul Colline and Paul Maye. It was one of several elements in the film which were prompted by Resnais's interest in "music-hall" and the theatre.[2]

Themes

At a press conference at the Venice Film Festival in 1963, Resnais said that his film depicted "the malaise of a so-called happy society. ...A new world is taking shape, my characters are afraid of it, and they don't know how to face up to it."[7] Muriel has been seen as part of a 'cinema of alienation' of the 1960s, films which "betray a sudden desperate nostalgia for certain essential values".[8] A sense of disruption and uncertainty is constantly emphasised, not least by the style of jump-cutting between events. "The technique of observing absolute chronology while simultaneously following a number of characters and treating even casual passers-by in the same manner as the main characters gives rise to a hallucinatory realism."[9]

At the centre of the film lies the specific theme of the Algerian war, which had only recently been brought to its troubled conclusion, and which it had hitherto been almost impossible for French film-makers to address in a meaningful way. (Godard's film about the war, Le Petit Soldat, had been banned in France in 1960 and was not shown until 1963. Also in 1960, Resnais had been one of the signatories of the Manifesto of the 121, in which a group of intellectuals had declared opposition to the French government's military policy in Algeria.) At the midpoint of Muriel, a sequence of newsreel with Bernard's voiceover commentary presents the inescapable 'evidence' of an incident of torture which continually haunts Bernard and explains his obsession with the girl he calls Muriel.

This "moment of truth" which has not been confronted is echoed in different forms in the past lives of each of the other main characters.[4]: 112 Hélène has been unable to overcome her sense of loss and betrayal from a past love affair; Hélène, Alphonse and Bernard all carry troubled memories of having lived through and survived World War II; and Boulogne itself presents the image of a town uneasily rebuilding itself over the devastation that it suffered in that war. Hélène's apartment, with its half-finished décor and ever-shifting furniture, and seen by the camera only as a disjointed collection of spaces until the film's final shot, offers a metaphor for the traumatised brain which is unable to put itself in order and see itself whole.[2]

Reception

The film was first presented in Paris on 24 July 1963, and it was then shown at the Venice Film Festival in September 1963. It was for the most part very badly received by both the press and the public. Resnais observed later that it had been his most expensive film to make and the one which had drawn perhaps the smallest audiences.[10] He also noted the paradox that it had subsequently become almost a cult film, attributing its difficulties for the public to the fact that its principal characters were people who continually made mistakes, which created a sense of unease.[11]

It nevertheless drew much attention from French film-makers and critics. François Truffaut, writing about the film in 1964, acknowledged its demanding nature but castigated critics for failing to engage with its core elements. "Muriel is an archetypically simple film. It is the story of several people who start each sentence with 'I...'." Truffaut also drew attention to the film's many allusions to Alfred Hitchcock (including the life-size cut-out of the director outside a restaurant); "his in-depth influence on many levels ... makes Muriel ... one of the most effective tributes ever rendered the 'master of suspense'".[12] The critic Jean-André Fieschi also made a connection with Hitchcock: "So we have a thriller, but a thriller where the enigma is the intention of the film itself and not its resolution".[13] Henri Langlois was one of several commentators who noted in Muriel a significantly innovative style and tone: "Muriel marks the advent of cinematic dodecaphony; Resnais is the Schoenberg of this chamber drama".[14]

Among English-language reviewers there was much perplexity about Muriel, described by the critic of The New York Times as "a very bewildering, annoying film".[15] The reviewer for The Times (London) shared an initial feeling of distrust and hostility, but admitted that "the film's stature increases with a second viewing".[16] This recognition that Muriel benefited from, or required, multiple viewings was something upon which a number of commentators have agreed.[17]

Susan Sontag, reviewing the film in 1963, deemed Muriel to be "the most difficult, by far, of Resnais' [first] three feature films", and went on to say that "although the story is not difficult to follow, Resnais' techniques for telling it deliberately estrange the viewer from the story". She found those techniques to be more literary than cinematic, and linked Resnais's liking for formalism with contemporary trends in new novels in France such as those of Michel Butor. While admiring the film for its intelligence and for the beauty of its visual composition, its performances, and its music, she remained dissatisfied by what she saw as its emotional coldness and detachment.[18]

The appearance of Muriel on DVD led to some reconsideration of its qualities, generally with greater sympathy than on its first appearance.[19] Many now rank it among Resnais's major works. The positive view of the film was summarized by Philip French: "It's a rich, beautifully acted masterpiece, at once cerebral and emotional, that rewards several viewings and is now less obscure than it seemed at the time".[20] In 2012, the film received four critics' votes and two directors' votes in the British Film Institute's decennial Sight & Sound polls.[21]

Awards

Delphine Seyrig won a Volpi Cup for best actress at the 1963 Venice Film Festival.

Restoration

A restored version of the film was released on DVD in France in 2004 by Argos Films/Arte France Développement from a distorted video master that squeezed the image into a 1.66:1 picture format.

A DVD version with English subtitles was issued in the UK in 2009 by Eureka, in the Masters of Cinema series. It uses the same transfer as the 2004 French DVD, but the mastering corrects the image resulting in a picture that fills out a "telecinema" screen format ratio of 1.78:1.

Argos later created a new high-definition scan after Resnais was shown the distorted video master used for the 2004 DVD. He approved the new HD master, which was subsequently utilized for the Criterion Blu-Ray release in 2016.[22]

References

- Jean Cayrol, Muriel: scénario et dialogues. (Paris: Seuil, 1963.)

- Interview with François Thomas, included with Arte DVD of Muriel (2004).

- James Monaco, Alain Resnais: the rôle of imagination. (London: Secker & Warburg, 1978.)

- Robert Benayoun, Alain Resnais, arpenteur de l'imaginaire. (Paris: Ramsay, 2008.)

- Suzanne Liandrat-Guigues & Jean-Louis Leutrat, Alain Resnais: liaisons secrètes, accords vagabonds. (Paris: Cahiers du Cinéma, 2006.) p. 225. "Tout ce qui pouvait donner cette impression d'inachèvement, de malaise, a été utilisé. ...La gageure du film c'était: on tourne en couleurs, c'est essentiel, on ne bouge jamais le pied de la caméra, on tourne avec huit jours de retard sur le scénario, on n'invente rien et on ne fait rien pour que cela fasse plus joli."

- François Thomas, L'Atelier de Alain Resnais. (Paris: Flammarion, 1989.)

- Robert Benayoun, Alain Resnais, arpenteur de l'imaginaire. (Paris: Ramsay, 2008.) pp. 110–111. "...le malaise d'une les civilisation dite du bonheur. ...Un nouveau monde se forme, mes personnages en ont peur, et ils ne savent pas y faire face."

- Robert Benayoun, Alain Resnais, arpenteur de l'imaginaire. (Paris: Ramsay, 2008.) p. 107. "Autant dire que les films trahissent une nostalgie soudaine, désesperée de certaines valeurs essentielles..."

- Roy Armes, French Cinema. (London: Secker & Warburg, 1985.) pp. 206–207.

- Suzanne Liandrat-Guigues & Jean-Louis Leutrat, Alain Resnais: liaisons secrètes, accords vagabonds. (Paris: Cahiers du Cinéma, 2006.) p. 225. "C'est mon film le plus cher et qui a peut-être le moins de spectateurs. Il a été très mal reçu par le presse et les gens ne sont pas venus de tout."

- Suzanne Liandrat-Guigues & Jean-Louis Leutrat, Alain Resnais: liaisons secrètes, accords vagabonds. (Paris: Cahiers du Cinéma, 2006.) p. 226. "Les films où les héros ne réussissent pas... je crois que c'est un ressort dramatique qui n'attire pas... Alphonse, ou Hélène, ou Bernard sont des gens qui ne cessent de faire des erreurs et cela crée un malaise."

- François Truffaut, The Films in My Life. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1978.) pp. 327–328.

- Quoted in the booklet accompanying the 2009 Eureka DVD (Masters of Cinema) p.36.

- Quoted in the booklet accompanying the 2009 Eureka DVD (Masters of Cinema) p.41. cf. Jacques Rivette: "Muriel is one of the first European films in which failure is not somehow sensed as inevitable, which, on the contrary, has a sense of the possible, and opening out on to the future in all its forms". (ibid. p.39.)

- Bosley Crowther, The New York Times, 31 October 1963.

- The Times (London), 19 March 1964, p.19 col.C.

- E.g. François Truffaut: "I have already seen Muriel three times without liking it completely, and maybe not liking the same things each time I saw it. I know that I'll see it again many times." (The Films in My Life. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1978. pp.328.). B. Kite: "There's always something else to say about the film. It keeps opening out even in its closing moments..." (Essay in the booklet accompanying the 2009 Eureka DVD (Masters of Cinema) p.23.)

- Susan Sontag, "Muriel ou le Temps d'un retour", in Film Quarterly, vol.17, no.2 (Winter 1963-1964), pp.23-27; reprinted, with amendments, as "Resnais' Muriel ", in S. Sontag, Against Interpretation: and other essays. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966.).

- See Rotten Tomatoes on Muriel (retrieved 19 Oct. 2010).

- The Observer, 29 March 2009.

- "Votes for Muriel ou Le Temps d'un retour (1963)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- Nick Wrigley in the CriterionForum, 04 March 2014. Archived at The Wayback Machine.

External links

- Muriel at IMDb

- Muriel at Rotten Tomatoes

- A commentary on Muriel at L'oBservatoire [in French]

- Muriel, or The Time of Return: Ashes of Time an essay by James Quandt at the Criterion Collection