Murshid Quli Khan

Murshid Quli Khan (Persian: مرشد قلی خان, Bengali: মুর্শিদকুলি খান; c. 1660 – 30 June 1727), also known as Zamin Ali Quli and born as Surya Narayan Mishra, was the first Nawab of Bengal, serving from 1717 to 1727.

| Murshid Quli Khan (Zamin Ali Quli) মুর্শিদকুলি খান | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasir Jung Ala ud-Daulah Mutam ul-Mulk Nawab Nazim Ja'far Khan Bahadur Nasiri | |||||

| |||||

| Nawab Nazim of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa | |||||

| Reign | 1717 – 30 June 1727 | ||||

| Coronation | 1717 | ||||

| Predecessor | Mughal Empire | ||||

| Successor | Shuja-ud-Din Muhammad Khan | ||||

| Born | Surya Narayan Mishra c. 1660 Deccan Plateau | ||||

| Died | 30 June 1727 (aged 66–67) Murshidabad (present day in West Bengal, India) | ||||

| Burial | Katra Masjid, Murshidabad, India | ||||

| Spouse | Nasiri Banu Begum | ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Nawabs of Bengal | ||||

| Dynasty | Nāṣirī | ||||

| Father | Haji Shafi Isfahani (foster father) | ||||

| Religion | Shia Islam[1][2][3] | ||||

| Resting place | Katra Masjid, Murshidabad, India 24.184722°N 88.288056°E | ||||

| Other names | Mohammad Hadi Mirza Hadi Ja'far Khan | ||||

| Military career | |||||

| Allegiance | |||||

| Service/ | Nawab of Bengal | ||||

| Rank | Nawab | ||||

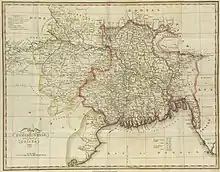

| History of Bangladesh |

|---|

|

|

|

Born a Hindu in the Deccan Plateau c. 1670, Murshid Quli Khan was bought by Mughal noble Haji Shafi. After Shafi's death, he worked under the Diwan of Vidarbha, during which time he piqued the attention of the then-emperor Aurangzeb, who sent him to Bengal as the divan c. 1700. However, he entered into a bloody conflict with the province's subahdar, Azim-us-Shan. After Aurangzeb's death in 1707, he was transferred to the Deccan Plateau by Azim-us-Shan's father the Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah I. However, he was brought back as deputy subahdar in 1710. In 1717, he was appointed as the Nawab Nazim of Murshidabad by Farrukhsiyar. During his reign, he changed the jagirdari system (land management) to the mal jasmani, which would later transform into the zamindari system. He also continued sending revenues from the state to the Mughal Empire. He built the Katra Masjid mosque at Murshidabad where he was buried under the steps of the staircase after his death on 30 June 1727. He was succeeded by his son-in-law Shuja ud Din Muhammad Khan.

Early life

Murshid Quli Khan was a Deccani Muslim.[5] According to Sir Jadunath Sarkar, Murshid Quli Khan was originally a Hindu and named as Surya Narayan Mishra, born in Deccan c. 1670.[6] The book Ma'asir al-umara supports this statement.[7] At the age of around ten years, he was sold to a Persian named Haji Shafi who converted him to Islam, circumcised him,[note 1] and raised him with the name Mohammad Hadi.[7] In c. 1690, Shafi left his position in the Mughal court and returned to Persia accompanied by Murshid Quli Khan. About five years after Shafi's death, Murshid returned to India and worked under Abdullah Khurasani, the Diwan of Vidarbha in the Mughal Empire. Due to his expertise in revenue matters, he was noticed by Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb and played an important role when applying the sharia based Fatwa Alamgiri's financial strategies.[7] Most of Murshid Quli Khan's associates, such as Alivardi Khan and Shuja-ud-Din Muhammad Khan, who gained power in Bengal were fellow Deccanis.[8]

Unlike other Islamic rulers, Murshid Quli Khan had only one wife, Nasiri Banu Begum, and no concubines. He had three children, two daughters and one son. One of his daughters became the wife of Nawab Shuja-ud-Din Muhammad Khan and mother of Sarfaraz Khan.[9]

First appointment in Bengal

Conflict with Azim-us-Shan

Aurangzeb appointed Quli Khan the Diwan of Bengal c. 1700. At that time, Azim-us-Shan, a grandson of the Mughal emperor, was the subahdar of the province. He was not pleased at this appointment as he intend to use the revenue collected from the state to fund his campaign to occupy the Mughal throne after Aurangzeb's death.[10] Immediately after being appointed to the post, Quli Khan went to Jahangirnagar (present day Dhaka) and transferred officials from the service of Azim-us-Shan to himself, enraging Azim-us-Shan.[10]

Assassination attempt

Azim-us-Shan planned to assassinate Quli Khan. Taking advantage of the fact the soldiers had yet to be paid, he convinced them that Quli Khan was responsible for the situation. He planned to have them surround Quli Khan on the pretext of confronting him over non-payment of their wages, and he would then be stabbed.[10]

One morning when Quli Khan was going to meet Azim-us-Shan, soldiers, under the leadership of Abdul Wahid, surrounded him and asked him for their wages. But, according to Historian Chowdhury, Quli Khan knew that us-Shan was responsible for inciting the soldiers,[10] so he said to them: "You have conspired to assassinate me. Remember that the Alamgir (Aurangzeb) will come to know everything. Abstain from doing such things, as it is a way of showing disrespect to the emperor. Be careful! If you kill me, then you will face dire consequences."[11]

Azim-us-Shan was extremely worried Quli Khan knew of his assassination plans and was fearful of Aurangzeb's reaction. Quli Khan behaved as if he knew nothing of the plan assuring us-Shan they would remain friends in the future. However, he wrote about the matter to Aurangzeb, who in turn sent a letter to us-Shan warning him that if Quli Khan was "harmed, then he would take revenge on him".[12]

Foundation of Murshidabad

Quli Khan felt unsafe in Dhaka, so he moved the diwani office to Mukshudabad.[note 2] He said that he relocated the office since Mukshudabad was situated in the central part of Bengal, making it easy to communicate throughout the province. As the city was on the banks of the Ganges, European trading companies had also set up their bases there. Quli Khan thought that it would be easy for him to keep a vigil over their actions. He also relocated the bankers to the new city. Azim-us-Shan felt betrayed as this was done without his permission. Historian Chowdhury says that Quli Khan was able to do this because he had the "support" of Aurangzeb.[14] A year later, in 1703, Aurangzeb transferred us-Shan from Bengal to Bihar and Farrukhsiyar was made the titular subahdar of the province. The subah office was then relocated to Mukshudabad. The city became a centre for all activities of the region.[14]

Quli Khan went to Bijapur to meet Aurangzeb, and to give him the revenue which was generated from the province. The emperor was happy with his work and gifted him clothes, flags, nagra, and a sword. He also gave him the title of Murshid Quli and gave him permission to rename the city Murshidabad (the city of Murshid Quli Khan), which he did when he returned to it.[11]

When the city was renamed is disputed by historians. Sir Jadunath Sarkar says that he was given the title on 23 December 1702, and his return to the city would have taken at least three months; so Mukshudabad was renamed in 1703.[15] But according to the newspaper Tarikh-i-Bangla, and Persian historian Riwaz-us-Salatin, the city was renamed in c. 1704. Chowdhury opines that this "might be the correct date" as the representative of the British East Indian Company in Orissa province met Quli Khan in early 1704. The fact that the first coins issued in Murshidabad are dated 1704 is strong evidence of the year of the name change.[16]

Reign

Death of Aurangzeb

Until the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, all the powers of the subahdar were vested in the hands of Quli Khan. He was succeeded by Azim-us-Shan's father Bahadur Shah I. He reappointed his son as the subahdar of the province and made Quli Khan his deputy. Azim-us-Shan influenced his father to throw Quli Khan out of the province. As a result, he was appointed the Diwan of Deccan in 1708, and served in the post until 1709.[17]

But, in 1710, Quli Khan was brought back as the diwan (revenue officer) of the province on the advice of us-Shan. According to Sarkar, he did so to form an allegiance with him, as he thought that it would be impossible to occupy the Delhi throne without the support of local nobility. Though he was brought back, his relationship with the Mughal prince remained strained.[18]

Shah was succeeded by Jahandar Shah in 1712, (27 February 1712 – 11 February 1713) and he was followed by Farrukhsiyar in 1713. In 1717,[note 3] he gave Quli Khan the title of Zafar Khan and made him the Subahdar of Bengal, thus holding both the post of subahdar and diwan at the same time. He declared himself the Nawab of Bengal and became the first independent nawab of the province.[19] The capital was shifted from Dhaka to Murshidabad.[20]

Revenue

Quli Khan replaced the Mughal jagirdari system with the mal jasmani system, which was similar to France's fermiers generals. He took security bonds from the contractors or ijardaars who later collected the land revenue. Though at first there remained many jagirdars, they were shortly squeezed out by the contractors, who later came to be known as zamindars.[21]

Quli Khan continued his policy of sending part of the revenue collected to the Mughal Empire. He did so even when the empire was in decline with the emperor vesting no power, as the power became concentrated in the hands of kingmakers. He justified his action by saying that it would be impossible to run the Mughal Empire without the revenue he sent. Historian Chowdhury says that his real reason was to show his loyalty to the Mughal Emperor so that he could run the state according to his own wishes.[20]

Records show that every year 1 crore 30 lakh rupees was sent as the revenue to the Mughal emperor. Besides money revenue was also paid in kind. Quli Khan himself used to carry the money and other forms of revenue with the infantry and the cavalry to Bihar where they were given to the Mughal collector.[22]

Structures built

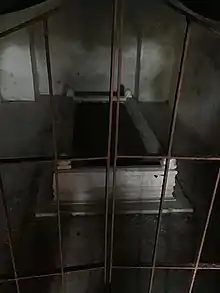

With Murshidabad evolving as the capital of Bengal, it became necessary for Quli Khan to build buildings and offices for work to be carried out from that city. In the Dugharia region of the city he built a palace, a diwankhana ("office of revenue collection", a court of exchequer). He also built an inn and a mosque for foreign travellers. He constructed a mint in the city in 1720.[22] In the eastern end of the city he built the Katra Masjid mosque in 1724 where he was buried after his death.[23]

Conditions in Murshidabad

During Quli Khan's reign the people of the Murshidabad used to participate in many festivals. One of them was the Punyah which occurred in the last week of the Bengali month of Chaitra. The zamindars, or their representatives, took part in it. However, the festival which was celebrated with the greatest pomp and grandeur was Mawlid the festival to celebrate the birth of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. During Mawlid people from neighbouring provinces came to the city to celebrate. On Quli Khan's order chirag or lamps were lit in all religious places such as mosques, and imambararas.[24]

Quli Khan also imitated the Mughal tradition of holding a durbar in the city which was attended by the city's bankers, foreign tourists, and European companies' representatives. Because of the increase in trade, a new class of businessmen arose who also attended his durbar. Due to his pious nature, Quli Khan followed Islam strictly and, according to Islamic rules, visitors were fed twice a day.[24]

The city used to be a major exporter of rice across India but c. 1720, Quli Khan prohibited all export of rice.[24] Chowdhury says that the condition of Hindus during his reign was "also good" as "they became more rich". Though Quli Khan was a Muslim, Hindus were employed in the tax department primarily because he thought they were experts in the field; they could also speak fluent Persian.[25]

Death and succession

Quli Khan died on 30 June 1727.[26] He was succeeded initially by his grandson Sarfaraz Khan. But his son-in-law Shuja-ud-Din Muhammad Khan did not accept the succession, and planned to fight a war against him. Khan gave up without a fight and Shuja-ud-Din became the nawab in 1727.[27] Sarfaraz would ascend the throne after his father's death in 1739 only to be defeated and replaced by Alivardi Khan in 1740.[28]

Quli Khan remains buried under the stairs to the main-floor of Katra Masjid[note 4]—a five-bayed rectangular mosque constructed by himself—pursuant to his wishes.[30][31] Popular belief holds the mosque to have been constructed of material obtained upon destruction of several Hindu temples and residences;[note 5] however, it is unlikely since the mosque shows an uniformity of material and Khan used to be an active patron of local temples.[32]

See also

Footnotes

- Shafi worked in various posts in the Mughal Empire which included Diwan-i-Tan and Dewan of Bengal.[7]

- According to Ain-i-Akbari, Mukshudabad was founded by a trader named Mukshud Khan in the sixteenth century who also built a sarai here. On Dutch traveller Valentijn's map, the city was shown as an island in the Ganges River. According to historian Nikhilnath Roy, during the reign of Sultan Hussain Shah, he was cured of fever by sage, so the city was named after it in 1702.[13]

- Historian Abdul Karim disputes the date and claims it to be 1716, but all other sources use 1717.[17]

- An inscription on the east façade of the mosque reads, "The triumph of Muhammad of Arabia is the glory of heaven and earth. One who be not the dust of his doorstep, dust be upon his head."[29]

- This finds a mention in Tarikh-i-Bangala (Munshi Salimullah; 1763-64) but not in the Riyaz-us-Salatin (Ghulam Husain Salīm Zaidpuri; 1787). Both the works were commissioned by officers of the East India Company; Zaidpuri had cited Salimullah among his sources.

Notes and references

Notes

- Rizvi, Saiyid Athar Abbas (1986). A Socio-intellectual History of the Isnā ʼAsharī Shīʼīs in India: 16th to 19th century A.D. Vol. 2. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. pp. 45–47.

- Rieck, Andreas (15 January 2016). The Shias of Pakistan: An Assertive and Beleaguered Minority. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-061320-4.

- K. K. Datta, Ali Vardi and His Times, ch. 4, University of Calcutta Press, (1939)

- Rai, R. History. FK Publications. p. 44. ISBN 9788187139690.

- Cátia A.P. Antunes, Francisco Bethencour (2022). Merchant Cultures:A Global Approach to Spaces, Representations and Worlds of Trade, 1500–1800. p. 124. ISBN 9789004506572.

Another Deccani, Shuja succeeded Murshid Quli from 1727.

- Sarkar, p.400

- Chowdhury, p.16

- Cátia A.P. Antunes, Francisco Bethencour (2022). Merchant Cultures:A Global Approach to Spaces, Representations and Worlds of Trade, 1500–1800. p. 124. ISBN 9789004506572.

Another Deccani, Shuja succeeded Murshid Quli from 1727.

- Chowdhury, p.87

- Chowdhury, p.17

- Sarkar, p.404

- Chowdhury, p.18

- Chowdhury, p.20

- Choudhury, p.19

- Sarkar, p.399

- Chowdhury, p.21

- Chowdhury, p.24

- Sarkar, p.405

- Sarkar, p.407

- Chowdhury, p.25

- U. A. B. Razia Akter Banu (1992). Islam in Bangladesh. E. J. Brill. p. 21. ISBN 978-90-04-09497-0.

- Chowdhury, p.26

- Begum, Ayesha (2012). "Katra Mosque, Murshidabad". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Chowdhury, p.27

- Chowdhury, p.28

- Mohammed Yamin. Impact of Islam on Orissan Culture. Readworthy. p. 46. ISBN 9789350181027.

- Chowdhury, p.29

- Chowdhury, p.30

- Asher, Catherine B. (1984). "Inventory of key monuments". In Michell, George (ed.). The Islamic Heritage of Bengal. UNESCO. pp. 206–207. ISBN 9231021745.

- Kabir, Nurul; Ahmed, Maliha Nargis (June 2013). "Exploring Khan Mohammad Mirdha Mosque: an Attempt to Construe the Socio-religious Fabric of Mughal Dhaka". Pratnatattva. Jahangirnagar University. 19.

- Sen, Samhita (2014). "Forgotten Nobles of Murshidabad: A Study through Its Architectural Heritage". Pratna Samiksha. Centre for Archaeological Studies & Training, Eastern India. New Series 5.

- Chaudhury, Sushil (2018). "Art and Architecture". Profile of a Forgotten Capital: Murshidabad in the Eighteenth Century. Delhi: Manohar. p. 164. ISBN 9789350981948.

References

- Sushil Chowdhury (2004). নবাবি আমলে মুর্শিদাবাদ (Nababi Amole Murshidabad). ISBN 9788177564358.

- Sarkar, Jadunath, ed. (1973) [First published 1948]. The History of Bengal. Vol. II: Muslim Period, 1200–1757. Patna: Academica Asiatica. OCLC 924890.