Muscle relaxant

A muscle relaxant is a drug that affects skeletal muscle function and decreases the muscle tone. It may be used to alleviate symptoms such as muscle spasms, pain, and hyperreflexia. The term "muscle relaxant" is used to refer to two major therapeutic groups: neuromuscular blockers and spasmolytics. Neuromuscular blockers act by interfering with transmission at the neuromuscular end plate and have no central nervous system (CNS) activity. They are often used during surgical procedures and in intensive care and emergency medicine to cause temporary paralysis. Spasmolytics, also known as "centrally acting" muscle relaxant, are used to alleviate musculoskeletal pain and spasms and to reduce spasticity in a variety of neurological conditions. While both neuromuscular blockers and spasmolytics are often grouped together as muscle relaxant,[1][2] the term is commonly used to refer to spasmolytics only.[3][4]

History

The earliest known use of muscle relaxant drugs was by natives of the Amazon Basin in South America who used poison-tipped arrows that produced death by skeletal muscle paralysis. This was first documented in the 16th century, when European explorers encountered it. This poison, known today as curare, led to some of the earliest scientific studies in pharmacology. Its active ingredient, tubocurarine, as well as many synthetic derivatives, played a significant role in scientific experiments to determine the function of acetylcholine in neuromuscular transmission.[5] By 1943, neuromuscular blocking drugs became established as muscle relaxants in the practice of anesthesia and surgery.[6]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of carisoprodol in 1959, metaxalone in August 1962, and cyclobenzaprine in August 1977.[7]

Other skeletal muscle relaxants of that type used around the world come from a number of drug categories and other drugs used primarily for this indication include orphenadrine (anticholinergic), chlorzoxazone, tizanidine (clonidine relative), diazepam, tetrazepam and other benzodiazepines, mephenoxalone, methocarbamol, dantrolene, baclofen.[7] Drugs once but no longer or very rarely used to relax skeletal muscles include meprobamate, barbiturates, methaqualone, glutethimide and the like; some subcategories of opioids have muscle relaxant properties, and some are marketed in combination drugs with skeletal and/or smooth muscle relaxants such as whole opium products, some ketobemidone, piritramide and fentanyl preparations and Equagesic.

Neuromuscular blockers

Muscle relaxation and paralysis can theoretically occur by interrupting function at several sites, including the central nervous system, myelinated somatic nerves, unmyelinated motor nerve terminals, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, the motor end plate, and the muscle membrane or contractile apparatus. Most neuromuscular blockers function by blocking transmission at the end plate of the neuromuscular junction. Normally, a nerve impulse arrives at the motor nerve terminal, initiating an influx of calcium ions, which causes the exocytosis of synaptic vesicles containing acetylcholine. Acetylcholine then diffuses across the synaptic cleft. It may be hydrolysed by acetylcholine esterase (AchE) or bind to the nicotinic receptors located on the motor end plate. The binding of two acetylcholine molecules results in a conformational change in the receptor that opens the sodium-potassium channel of the nicotinic receptor. This allows Na+

and Ca2+

ions to enter the cell and K+

ions to leave the cell, causing a depolarization of the end plate, resulting in muscle contraction.[8] Following depolarization, the acetylcholine molecules are then removed from the end plate region and enzymatically hydrolysed by acetylcholinesterase.[5]

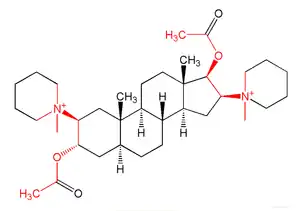

Normal end plate function can be blocked by two mechanisms. Nondepolarizing agents, such as tubocurarine, block the agonist, acetylcholine, from binding to nicotinic receptors and activating them, thereby preventing depolarization. Alternatively, depolarizing agents, such as succinylcholine, are nicotinic receptor agonists which mimic Ach, block muscle contraction by depolarizing to such an extent that it desensitizes the receptor and it can no longer initiate an action potential and cause muscle contraction.[5] Both of these classes of neuromuscular blocking drugs are structurally similar to acetylcholine, the endogenous ligand, in many cases containing two acetylcholine molecules linked end-to-end by a rigid carbon ring system, as in pancuronium (a nondepolarizing agent).[5]

Spasmolytics

The generation of the neuronal signals in motor neurons that cause muscle contractions is dependent on the balance of synaptic excitation and inhibition the motor neuron receives. Spasmolytic agents generally work by either enhancing the level of inhibition or reducing the level of excitation. Inhibition is enhanced by mimicking or enhancing the actions of endogenous inhibitory substances, such as GABA.

Terminology

Because they may act at the level of the cortex, brain stem, or spinal cord, or all three areas, they have traditionally been referred to as "centrally acting" muscle relaxants. However, it is now known not every agent in this class has CNS activity (e.g. dantrolene), so this name is inaccurate.[5]

Most sources still use the term "centrally acting muscle relaxant". According to MeSH, dantrolene is usually classified as a centrally acting muscle relaxant.[9] The World Health Organization, in its ATC, uses the term "centrally acting agents",[10] but adds a distinct category of "directly acting agents", for dantrolene.[11] Use of this terminology dates back to at least 1973.[12]

The term "spasmolytic" is also considered a synonym for antispasmodic.[13]

Clinical use

Spasmolytics such as carisoprodol, cyclobenzaprine, metaxalone, and methocarbamol are commonly prescribed for low back pain or neck pain, fibromyalgia, tension headaches and myofascial pain syndrome.[14] However, they are not recommended as first-line agents; in acute low back pain, they are not more effective than paracetamol or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),[15][16] and in fibromyalgia they are not more effective than antidepressants.[14] Nevertheless, some (low-quality) evidence suggests muscle relaxants can add benefit to treatment with NSAIDs.[17] In general, no high-quality evidence supports their use.[14] No drug has been shown to be better than another, and all of them have adverse effects, particularly dizziness and drowsiness.[14][16] Concerns about possible abuse and interaction with other drugs, especially if increased sedation is a risk, further limit their use.[14] A muscle relaxant is chosen based on its adverse-effect profile, tolerability, and cost.[18]

Muscle relaxants (according to one study) were not advised for orthopedic conditions, but rather for neurological conditions such as spasticity in cerebral palsy and multiple sclerosis.[14] Dantrolene, although thought of primarily as a peripherally acting agent, is associated with CNS effects, whereas baclofen activity is strictly associated with the CNS.

Muscle relaxants are thought to be useful in painful disorders based on the theory that pain induces spasm and spasm causes pain. However, considerable evidence contradicts this theory.[17]

In general, muscle relaxants are not approved by FDA for long-term use. However, rheumatologists often prescribe cyclobenzaprine nightly on a daily basis to increase stage 4 sleep. By increasing this sleep stage, patients feel more refreshed in the morning. Improving sleep is also beneficial for patients who have fibromyalgia.[19]

Muscle relaxants such as tizanidine are prescribed in the treatment of tension headaches.[20]

Diazepam and carisoprodol are not recommended for older adults, pregnant women, or people who have depression or for those with a history of drug or alcohol addiction.[21]

Mechanism

Because of the enhancement of inhibition in the CNS, most spasmolytic agents have the side effects of sedation and drowsiness and may cause dependence with long-term use. Several of these agents also have abuse potential, and their prescription is strictly controlled.[22][23][24]

The benzodiazepines, such as diazepam, interact with the GABAA receptor in the central nervous system. While it can be used in patients with muscle spasm of almost any origin, it produces sedation in most individuals at the doses required to reduce muscle tone.[5]

Baclofen is considered to be at least as effective as diazepam in reducing spasticity, and causes much less sedation. It acts as a GABA agonist at GABAB receptors in the brain and spinal cord, resulting in hyperpolarization of neurons expressing this receptor, most likely due to increased potassium ion conductance. Baclofen also inhibits neural function presynaptically, by reducing calcium ion influx, and thereby reducing the release of excitatory neurotransmitters in both the brain and spinal cord. It may also reduce pain in patients by inhibiting the release of substance P in the spinal cord, as well.[5][25]

Clonidine and other imidazoline compounds have also been shown to reduce muscle spasms by their central nervous system activity. Tizanidine is perhaps the most thoroughly studied clonidine analog, and is an agonist at α2-adrenergic receptors, but reduces spasticity at doses that result in significantly less hypotension than clonidine.[26] Neurophysiologic studies show that it depresses excitatory feedback from muscles that would normally increase muscle tone, therefore minimizing spasticity.[27][28] Furthermore, several clinical trials indicate that tizanidine has a similar efficacy to other spasmolytic agents, such as diazepam and baclofen, with a different spectrum of adverse effects.[29]

The hydantoin derivative dantrolene is a spasmolytic agent with a unique mechanism of action outside of the CNS. It reduces skeletal muscle strength by inhibiting the excitation-contraction coupling in the muscle fiber. In normal muscle contraction, calcium is released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum through the ryanodine receptor channel, which causes the tension-generating interaction of actin and myosin. Dantrolene interferes with the release of calcium by binding to the ryanodine receptor and blocking the endogenous ligand ryanodine by competitive inhibition. Muscle that contracts more rapidly is more sensitive to dantrolene than muscle that contracts slowly, although cardiac muscle and smooth muscle are depressed only slightly, most likely because the release of calcium by their sarcoplasmic reticulum involves a slightly different process. Major adverse effects of dantrolene include general muscle weakness, sedation, and occasionally hepatitis.[5]

Other common spasmolytic agents include: methocarbamol, carisoprodol, chlorzoxazone, cyclobenzaprine, gabapentin, metaxalone, and orphenadrine.

Thiocolchicoside is a muscle relaxant with anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects and an unknown mechanism of action.[30][31][32][33] It acts as a competitive antagonist at GABAA and glycine receptors with similar potencies, as well as at nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, albeit to a much lesser extent.[34][35] It has powerful proconvulsant activity and should not be used in seizure-prone individuals.[36][37][38]

Side effects

Patients most commonly report sedation as the main adverse effect of muscle relaxants. Usually, people become less alert when they are under the effects of these drugs. People are normally advised not to drive vehicles or operate heavy machinery while under muscle relaxants' effects.

Cyclobenzaprine produces confusion and lethargy, as well as anticholinergic side effects. When taken in excess or in combination with other substances, it may also be toxic. While the body adjusts to this medication, it is possible for patients to experience dry mouth, fatigue, lightheadedness, constipation or blurred vision. Some serious but unlikely side effects may be experienced, including mental or mood changes, possible confusion and hallucinations, and difficulty urinating. In a very few cases, very serious but rare side effects may be experienced: irregular heartbeat, yellowing of eyes or skin, fainting, abdominal pain including stomach ache, nausea or vomiting, lack of appetite, seizures, dark urine or loss of coordination.[39]

Patients taking carisoprodol for a prolonged time have reported dependence, withdrawal and abuse, although most of these cases were reported by patients with addiction history. These effects were also reported by patients who took it in combination with other drugs with abuse potential, and in fewer cases, reports of carisoprodol-associated abuse appeared when used without other drugs with abuse potential.[40]

Common side effects eventually caused by metaxalone include dizziness, headache, drowsiness, nausea, irritability, nervousness, upset stomach and vomiting. Severe side effects may be experienced when consuming metaxalone, such as severe allergic reactions (rash, hives, itching, difficulty breathing, tightness in the chest, swelling of the mouth, face, lips, or tongue), chills, fever, and sore throat, may require medical attention. Other severe side effects include unusual or severe tiredness or weakness, as well as yellowing of the skin or the eyes.[41] When baclofen is administered intrathecally, it may cause CNS depression accompanied with cardiovascular collapse and respiratory failure. Tizanidine may lower blood pressure. This effect can be controlled by administering a low dose at the beginning and increasing it gradually.[42] [43]

References

- "Definition of Muscle relaxant." MedicineNet.com. (c) 1996–2007. Retrieved on September 19, 2007.

- "muscle relaxant Archived 2013-10-06 at the Wayback Machine." mediLexicon Archived 2013-10-06 at the Wayback Machine. (c) 2007. Retrieved on September 19, 2007.

- "Muscle relaxants." WebMD. Last Updated: February 15, 2006. Retrieved on September 19, 2007.

- "Skeletal Muscle Relaxant (Oral Route, Parenteral Route)." Mayo Clinic. Last Updated: April 1, 2007. Retrieved on September 19, 2007.

- Miller, R.D. (1998). "Skeletal Muscle Relaxants". In Katzung, B.G. (ed.). Basic & Clinical Pharmacology (7th ed.). Appleton & Lange. pp. 434–449. ISBN 0-8385-0565-1.

- Bowman WC (January 2006). "Neuromuscular block". Br. J. Pharmacol. 147 (Suppl 1): S277–86. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706404. PMC 1760749. PMID 16402115.

- "Brief History". Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- Craig, C.R.; Stitzel, R.E. (2003). Modern Pharmacology with clinical applications. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 339. ISBN 0-7817-3762-1.

- Dantrolene at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- "M03B Muscle Relaxants, Centrally acting agents". ATC/DDD Index. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology.

- "M03CA01 Dantrolene". ATC/DDD Index. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology.

- Ellis KO, Castellion AW, Honkomp LJ, Wessels FL, Carpenter JE, Halliday RP (June 1973). "Dantrolene, a direct acting skeletal muscle relaxant". J Pharm Sci. 62 (6): 948–51. doi:10.1002/jps.2600620619. PMID 4712630.

- "Dorlands Medical Dictionary:antispasmodic". Archived from the original on 2009-10-01.

- See S, Ginzburg R (2008). "Choosing a skeletal muscle relaxant". Am Fam Physician. 78 (3): 365–370. ISSN 0002-838X. PMID 18711953.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT, Shekelle P, Owens DK (October 2007). "Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society". Ann. Intern. Med. 147 (7): 478–91. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006. PMID 17909209.

- van Tulder MW, Touray T, Furlan AD, Solway S, Bouter LM (2003). "Muscle relaxants for non-specific low back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 (2): CD004252. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004252. PMC 6464310. PMID 12804507.

- Beebe FA, Barkin RL, Barkin S (2005). "A clinical and pharmacologic review of skeletal muscle relaxants for musculoskeletal conditions". Am J Ther. 12 (2): 151–71. doi:10.1097/01.mjt.0000134786.50087.d8. PMID 15767833. S2CID 24901082.

- See S, Ginzburg R (February 2008). "Skeletal muscle relaxants". Pharmacotherapy. 28 (2): 207–13. doi:10.1592/phco.28.2.207. PMID 18225966. S2CID 43152771.

- "When Are Muscle Relaxers Prescribed For Arthritis Patients?". Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Tension Headache

- "Muscle Relaxants". Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- Rang, H.P.; Dale, M.M. (1991). "Drugs Used in Treating Motor Disorders". Pharmacology (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingston. pp. 684–705. ISBN 0-443-04483-X.

- Standaert, D.G.; Young, A.B. (2001). "Treatment Of Central Nervous System Degerative Disorders". In Goodman, L.S.; Hardman, J.G.; Limbird, L.E.; Gilman, A.G. (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (10th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 550–568. ISBN 0-07-112432-2.

- Charney, D.S.; Mihic, J.; Harris, R.A. (2001). "Hypnotics and Sedatives". Goodman & Gilman's. pp. 399–427.

- Cazalets JR, Bertrand S, Sqalli-Houssaini Y, Clarac F (November 1998). "GABAergic control of spinal locomotor networks in the neonatal rat". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 860 (1): 168–80. Bibcode:1998NYASA.860..168C. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09047.x. PMID 9928310. S2CID 33042651.

- Young, R.R., ed. (1994). "Symposium: Role of tizanidine in the treatment of spasticity". Neurology. 44 (Suppl 9): S1-80. PMID 7970005.

- Bras H, Jankowska E, Noga B, Skoog B (1990). "Comparison of Effects of Various Types of NA and 5-HT Agonists on Transmission from Group II Muscle Afferents in the Cat". Eur. J. Neurosci. 2 (12): 1029–1039. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.1990.tb00015.x. PMID 12106064. S2CID 13552923.

- Jankowska E, Hammar I, Chojnicka B, Hedén CH (February 2000). "Effects of monoamines on interneurons in four spinal reflex pathways from group I and/or group II muscle afferents". Eur. J. Neurosci. 12 (2): 701–14. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00955.x. PMID 10712650. S2CID 21546330.

- Young RR, Wiegner AW (June 1987). "Spasticity". Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. (219): 50–62. PMID 3581584.

- Tüzün F, Unalan H, Oner N, Ozgüzel H, Kirazli Y, Içağasioğlu A, Kuran B, Tüzün S, Başar G (September 2003). "Multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of thiocolchicoside in acute low back pain". Joint, Bone, Spine. 70 (5): 356–61. doi:10.1016/S1297-319X(03)00075-7. PMID 14563464.

- Ketenci A, Basat H, Esmaeilzadeh S (July 2009). "The efficacy of topical thiocolchicoside (Muscoril) in the treatment of acute cervical myofascial pain syndrome: a single-blind, randomized, prospective, phase IV clinical study". Agri. 21 (3): 95–103. PMID 19780000.

- Soonawalla DF, Joshi N (May 2008). "Efficacy of thiocolchicoside in Indian patients suffering from low back pain associated with muscle spasm". Journal of the Indian Medical Association. 106 (5): 331–5. PMID 18839644.

- Ketenci A, Ozcan E, Karamursel S (July 2005). "Assessment of efficacy and psychomotor performances of thiocolchicoside and tizanidine in patients with acute low back pain". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 59 (7): 764–70. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00454.x. PMID 15963201. S2CID 20671452.

- Carta M, Murru L, Botta P, Talani G, Sechi G, De Riu P, Sanna E, Biggio G (September 2006). "The muscle relaxant thiocolchicoside is an antagonist of GABAA receptor function in the central nervous system". Neuropharmacology. 51 (4): 805–15. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.05.023. PMID 16806306. S2CID 11390033.

- Mascia MP, Bachis E, Obili N, Maciocco E, Cocco GA, Sechi GP, Biggio G (March 2007). "Thiocolchicoside inhibits the activity of various subtypes of recombinant GABA(A) receptors expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes". European Journal of Pharmacology. 558 (1–3): 37–42. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.076. PMID 17234181.

- De Riu PL, Rosati G, Sotgiu S, Sechi G (August 2001). "Epileptic seizures after treatment with thiocolchicoside". Epilepsia. 42 (8): 1084–6. doi:10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.0420081084.x. PMID 11554898. S2CID 24017279.

- Giavina-Bianchi P, Giavina-Bianchi M, Tanno LK, Ensina LF, Motta AA, Kalil J (June 2009). "Epileptic seizure after treatment with thiocolchicoside". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 5 (3): 635–7. doi:10.2147/tcrm.s4823. PMC 2731019. PMID 19707540.

- Sechi G, De Riu P, Mameli O, Deiana GA, Cocco GA, Rosati G (October 2003). "Focal and secondarily generalised convulsive status epilepticus induced by thiocolchicoside in the rat". Seizure. 12 (7): 508–15. doi:10.1016/S1059-1311(03)00053-0. PMID 12967581. S2CID 14308541.

- "Cyclobenzaprine-Oral". Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- "Carisoprodolx". Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- "Side Effects of Metaxalone – for the Consumer". Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- "Precautions". Encyclopedia of Surgery. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- "Carisoprodol". Retrieved 2021-03-12.

External links

- Skeletal+Muscle+Relaxants at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)