Vecuronium bromide

Vecuronium bromide, sold under the brand name Norcuron among others, is a medication used as part of general anesthesia to provide skeletal muscle relaxation during surgery or mechanical ventilation.[1] It is also used to help with endotracheal intubation; however, agents such as suxamethonium (succinylcholine) or rocuronium are generally preferred if this needs to be done quickly.[1] It is given by injection into a vein.[1] Effects are greatest at about 4 minutes and last for up to an hour.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Norcuron, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 100% (IV) |

| Metabolism | liver 30% |

| Onset of action | < 1 min[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 51–80 minutes (longer with kidney failure) |

| Duration of action | 15 - 30 min[2] |

| Excretion | Fecal (40–75%) and kidney (30% as unchanged drug and metabolites) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.051.549 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

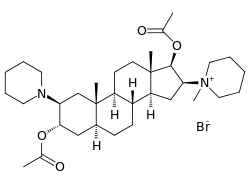

| Formula | C34H57BrN2O4 |

| Molar mass | 637.744 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Side effects may include low blood pressure and prolonged paralysis.[3] Allergic reactions are rare.[4] It is unclear if use in pregnancy is safe for the baby.[1]

Vecuronium is in the aminosteroid neuromuscular-blocker family of medications and is of the non-depolarizing type.[1] It works by competitively blocking the action of acetylcholine on skeletal muscles.[1] The effects may be reversed with sugammadex or a combination of neostigmine and glycopyrrolate. To minimize residual blockade, reversal should only be attempted if some degree of spontaneous recovery has been achieved.[1]

Vecuronium was approved for medical use in the United States in 1984[1] and is available as a generic medication.[1] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5][6]

Mechanism of action

Vecuronium operates by competing for the cholinoceptors at the motor end plate, thereby exerting its muscle-relaxing properties, which are used adjunctively to general anesthesia. Under balanced anesthesia, the time to recovery to 25% of control (clinical duration) is approximately 25 to 40 minutes after injection and recovery is usually 95% complete approximately 45 to 65 minutes after injection of an intubating dose. The neuromuscular blocking action of vecuronium is slightly enhanced in the presence of potent inhalation anesthetics. If vecuronium is first administered more than 5 minutes after the start of the inhalation of enflurane, isoflurane, or halothane, or when a steady state has been achieved, the intubating dose of vecuronium may be decreased by approximately 15%.

Vecuronium has an active metabolite, 3-desacetyl-vecuronium, that has 80% of the effect of vecuronium. Accumulation of this metabolite, which is cleared by the kidneys, can prolong the duration of action of the drug, particularly when an infusion is used in a person with kidney failure.[1]

Reversal of vecuronium can be accomplished by administration of sugammadex which is a γ-cyclodextrin which encapsulates vecuronium preventing it from binding to receptors.[7] Reversal can also be accomplished with neostigmine or other cholinesterase inhibitors, but their efficacy is lower than that of sugammadex.[8]

History

As long ago as 1862, adventurer Don Ramon Paez described a Venezuelan poison, guachamaca, which the indigenous peoples used to lace sardines as bait for herons and cranes. If the head and neck of a bird so killed was cut off, the remainder of the flesh could be eaten safely. Paez also described the attempt of a Llanero woman to murder a rival to her lover's affections with guachamaca and unintentionally killed 10 other people when her husband shared his food with their guests.[9] It is probable that the plant was Malouetia nitida or Malouetia schomburgki.[10]

The genus Malouetia (family Apocynaceae) is found in both South America and Africa. The botanist Robert E. Woodson Jr comprehensively classified the American species of Malouetia in 1935. At that time, only one African species of Malouetia was recognized, but the following year Woodson described a second: Malouetia bequaertiana, from the Belgian Congo.[10]

In 1960, scientists reported the isolation of malouetine from the roots and bark of Malouetia bequaertiana Woodson by means of an ion exchange technique. Optimization of the aminosteroid nucleus led to a sequence of synthesized derivatives, ultimately leading to pancuronium bromide in 1964. The name was derived from p(iperidino)an(drostane)cur(arising)-onium.[10]

A paper published in 1973 discussed the structure-activity relationships of a series of aminosteroid muscle relaxants, including the mono-quaternary analogue of pancuronium, later called vecuronium.[10]

Society and culture

Non-medical use

Vecuronium bromide has been used as part of a drug cocktail that prisons in the United States use for execution by lethal injection. Vecuronium is used to paralyze the prisoner and stop his or her breathing, in conjunction with a sedative and potassium chloride to stop the prisoner's heart. Injections of vecuronium bromide without proper sedation allow the person to be fully awake but unable to move in response to pain.[11]

In 2001, Japanese nurse Daisuke Mori was reported to have murdered 10 patients using vecuronium bromide.[12] He was convicted of murder and was sentenced to life imprisonment.[13]

References

- "Vecuronium Bromide". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Hamilton R (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 23. ISBN 9781284057560.

- "NORCURON 10mg - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". www.medicines.org.uk. 4 August 2000. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 431. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. "Bridion (sugammadex) Injection" (PDF). Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Carron M, Zarantonello F, Tellaroli P, Ori C (December 2016). "Efficacy and safety of sugammadex compared to neostigmine for reversal of neuromuscular blockade: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 35: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.06.018. PMID 27871504.

- Páez R (1 January 1862). Wild Scenes in South America, Or, Life in the Llanos of Venezuela. C. Scribner. pp. 206–208.

A dreadful case of poisoning by means of this plant had just occurred at Nutrias soon after our arrival on the Apure which created for a time great excitement even amidst that scattered population

- McKenzie AG (June 2000). "Prelude to pancuronium and vecuronium". Anaesthesia. 55 (6): 551–556. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01423.x. PMID 10866718. S2CID 22476701.

- "One Execution Botched, Oklahoma Delays the Next". The New York Times. 29 April 2014. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014.

- "Japanese nurse kills 10 patients, says wanted to trouble hospital". The Indian Express. 10 January 2001. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- "Nurse gets life for patient slaying". The Japan Times Weekly. 10 April 2004. Archived from the original on 1 April 2010. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

External links

- "Vecuronium Bromide". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.