Museum Europäischer Kulturen

The Museum of European Cultures (German: Museum Europäischer Kulturen) – National Museums in Berlin – Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation came from the unification of the Europe-Department in the Berlin Museum of Ethnography and the Berlin Museum for Folklore in 1999. The museum focuses on the lived-in world of Europe and European culture contact, predominantly in Germany from the 18th Century until today.

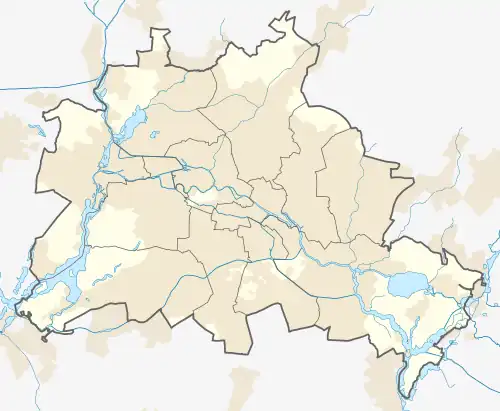

The museum, together with the Ethnological Museum of Berlin and the Museum of Asian Art, is located in the Dahlem Museums. The building was named after the architect Bruno Paul (1874–1968) and is located in the modern district of Steglitz-Zehlendorf. The museum's exhibition rooms occupy the oldest building in the Dahlem Museums. In 2019, the Museum of European Cultures recorded 24,000 visitors.[1]

History

The current Museum of European Cultures was established from several previous institutions which arose at the beginning of the 19th century and are due in part to private initiatives as well as governmental foundations.

The Europe Cabinet

The basis of the exhibit was two shaman drums of the northern European Sámi which came to the Königlich Preußische Kunstkammer (Royal Prussian Art Collection) at the beginning of the 19th century. In 1859 the Neues Museum opened which, among others, had an ethnological collection. This collection also held the "Europa" Cabinet, which surmises the nucleus of the current Museum for European Cultures.

Museum for Folklore

The Ethnological Museum of the Königlich Preußischen Museen (Royal Prussian Museums) was institutionally founded in 1873. In 1886 the Museum opened in a new building, which also contained European ethnographica, although no collections explicitly from Germany. Plans for a combined exhibit of both non-European objects and European objects, with special consideration of German culture, failed both because of lack of room as well as the founding of a "National Museum", which presented the history of the European "folk" with a focus on German culture from pre-history until the then present day.[2]

Museum for German Traditional Costumes and Handicrafts

The private initiative of the Berliner physician, anthropologist, and politician Rudolf Virchow (1821–1902) and other members of the Berliner Anthropoligischen Gesellschaft (Berlin Anthropological Organization) led in 1889 to the founding and facilitation of the first Germany-wide central "Museum für deutsche Volkstrachten und Erzeugnisses des Hausgewerbes" (Museum for German Traditional Costumes and Handicrafts). From 1891 the Museum was financed through the Museum Association which was specifically established for this purpose. The goal of the museum was to give room to the cultural objects of their "own people" that had been excluded in ethnology as well as bordering, German-speaking lands. Furthermore, the material goods from the country and farms, which in the wake of Industrialization had begun to disappear, would be protected.[3]

Royal Collection for German Folklore

The private Museum for German Traditional Costume and Handicrafts, with the support of the Patron James Simon (1851–1932, from 1904 President of the Museum's Association) and under the leadership of Karl Brunner (1904–1928), was in 1904 made part of the "Königliche Sammlung für Deutsche Volkskunde" (Royal Collection for German Folklore), part of the Königlich Preußischen Museen zu Berlin. The institution would administratively shelter and take care of the prehistoric department of the Museum for Ethnology. Due to the inexpedient incorporation of the department, the folklore collection there played only a marginal role.[4]

Staatliches Museum für deutsche Volkskunde

First in 1929 an independent „Staatliches Museum für deutsche Volkskunde" (State Museum for German Folklore) was established. This museum was legally supported by the National Museums of Berlin. Director Konrad Hahm (1928–1943) preoccupied himself with intensive public work, varying exhibits, and purposeful lectures so that the richness and variety of the museum's collections could be made known to a large audience. On top of that, he compiled numerous memoirs and conceptions of various forms of the folklore performances in a central Folklore Museum. From 1934 until 1945 the Museum for German Folklore received its own building in the Bellevue Palace. The relocation of the exhibition and administration buildings to the Prinzessinnenpalais (Princess Palace) next to the Berlin State Opera on Unter den Linden followed in 1938. The collections and workshops were moved as well into the former main building of the German Freemasons in the Splittgerbergasse. Occasionally, the museum made concessions to the ruling ideology of National Socialism. However, numerous exhibits coined from National Socialism and large propaganda shows were not achieved.

Konrad Hahm dedicated himself to the founding of an "Instituts für Volkskunstforschung" (Institute for Folk Art Research) that under his guidance became associated with the Berlin University in 1940. One of the museum affiliated branches, "Schule und Museum" (School and Museum) appeared as early as 1939 in a museum pedagogic perspective. Adolf Reichwein, a progressive and humanistic educator and active resistance fighter in the Kreisau Circle, took over leadership until his arrest and later execution in October 1944.

With the establishment of a "Eurasian" department in the Museum for Ethnology, whose institution was consistent with the National Socialist ideology, the folklore collections had to give all of their "non-German" collection to the Museum for Ethnology. The museum, meanwhile, had to transfer all of their "German" objects to the Museum for German Folklore. Thereby a new institutional separation occurred between the two fields. In World War II, the museums lost numerous objects due to destruction, looting, and relocation to other places.[5]

Parallel Folklore Museums in East and West (1945–1989)

Although the most valuable items of the museums' collection were evacuated to nine different places in Berlin, Brandenburg, and Vorpommern in the last years of the war, around 80% of the collection was destroyed. The objects from the Berlin Flak Tower at the Zoo that were brought to Thuringia were carried from US garrisons back to Wiesbaden. The Soviet occupying forces transported the objects that remained at the flak tower as well as other valuable museum goods back to the Soviet Union in the summer of 1945.[6]

The political separation of post-war Germany led to the foundation of two parallel museums in Berlin: a part of the collection was housed in the "Museum für Volkskunde" (Museum for Folklore) in the Pergamon Museum on the Museum Island, where after contextual-conceptual controversy it finally established itself with a new public collection. The other part in West Berlin was shortly affiliated with the Museum for Ethnology, but won its autonomy in the framework of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation as the "Museum für Deutsche Volkskunde" (Museum for German Folklore) in 1963. Even so, it was first in 1976 when the museum moved to the reopened warehouse wing of the Prussian Privy State Archives in Berlin-Dahlem that it was accessible to the public. A ministerial dictate that forbid employees of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (East) to have contact with institutions of the Preußischen Kulturbesitzes in Berlin (West) was a crucial factor to the estrangement of both institutions.[7]

In the 1980s both museums increasingly dedicated themselves to the cultural change from the industrial era right up to the life of the city dweller. With special exhibitions like "Großstadtproletariat" (Big City Proletariat) (1980–87) or "Dienstbare Geister" (Willing Hands) (1981) the museums were able to overcome the confinements of the pre-industrial country and farm culture. The aspiration of the collection-politic to direct itself to modern dynamics was only partly fulfilled.[8] After the cooperation between the European Department of the Museum for Ethnology and the Museum for German Folklore, the idea came about in 1988 to found a "European Museum" as a reaction to the social and cultural processes of change as part of the advanced political and economical European integration.[9]

During the celebrations for the 100-year anniversary in 1989 of the Museums for (German) Folklore the latent contact between the two museums began to revive.

Museum for Folklore by the National Museums in Berlin /Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

In connect to the political reunification of Germany the collections of the State Museums were brought together with the support of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. As part of the new orientation the separated museum inventories we initially unified into the "Museum für Volkskunde bei den Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin/Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz" (Museum for Folklore by the National Museums in Berlin /Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation). This complex organizational challenge triggered a wave of controversial contentual/conceptual discussions that entailed reconciling and compromising in regards to the prospective structure of the museum. The original idea from the Museum for Ethnology at the end of the 1980s for a new concept of a museum with a European direction was elaborated: the Europe Department and the Museum for Folklore would be consolidated into one new museum.[10]

Museum of European Cultures

As a result, the Museum of European Cultures, with its new programmatic direction, was founded in 1999. This new founding took into account the present societal, political, and cultural developments in Europe. The Museum explored historical, cultural, and nationalistic borders between the "us" and the purportedly foreign "them". The museum also documented and collected, within European context, international exchange processes of the every day life of European societies and its accompanying changes. At the same time the museum busies itself with issues of the plural society in Germany, such as migrant movements, cultural diversity, its expression and societal effects, especially in urban settings.

The museum moved its exhibits to the Dahlem Museums in 2011 in the Bruno-Paul Building in Arnimallee 25. The workshops, warehouse, and employee offices can still be found in the old exhibit rooms on Im Winkel 6/8.

References

- Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu. "Besuchszahlen 2019 der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin". www.smb.museum (in German). Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- Karasek, Erika/Tietmeyer, Elisabeth (1999): „Das Museum Europäischer Kulturen: Entstehung – Realität – Zukunft, in: Karasek, u.a. (Hg.): Faszination Bild. Kulturkontakte in Europa, Potsdam Pg. 7–19, Pg. 8f.

- Tietmeyer, Elisabeth (2003): „Wie gegenwartsorientiert können ethnologische Museen Kulturen der Welt darstellen?" In: Martina Krause, Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow, Karoline Noack (Hg.), Ethnografisches Arbeiten in Berlin. Wissenschaftsgeschichtliche Annäherungen, Berliner Blätter. Ethnographische und ethnologische Beiträge, Issue 31, Pg. 75–83, Pg. 77.

- Tietmeyer, Elisabeth (2003): „Wie gegenwartsorientiert können ethnologische Museen Kulturen der Welt darstellen?" In: Martina Krause, Dagmar Neuland-Kitzerow, Karoline Noack (Hg.), Ethnografisches Arbeiten in Berlin. Wissenschaftsgeschichtliche Annäherungen, Berliner Blätter. Ethnographische und ethnologische Beiträge, Issue 31, Pg. 75–83, Pg. 77.

- Tietmeyer, Elisabeth (2001): „Tarnung oder Opportunismus? Der Berliner Museumsethnologe Kunz Dittmer im Nationalsozialismus", in: Berliner Blätter, Ethnographische und ethnologische Beiträge, 22, Pg. 31–41.

- Karasek, Erika (2010): „Vom Museum für Deutsche Volkskunde zum Museum Europäischer Kulturen", in: Akteure, Praxen, Theorien. Der Ethnografin Ute Mohrmann zum siebzigsten Geburtstag, Berliner Blätter, Book 52, Pg. 38–46, Pg. 38f.

- Karasek 1989, Pg. 45.

- Tietmeyer, Elisabeth (2003), Pg. 81

- Karasek 2010, Pg. 45

- Karasek 2010, Pg. 45