Malate dehydrogenase (oxaloacetate-decarboxylating) (NADP+)

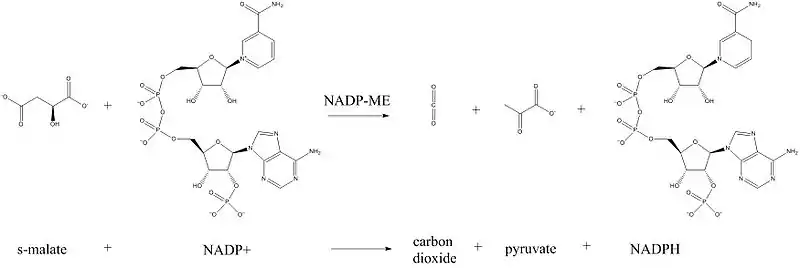

Malate dehydrogenase (oxaloacetate-decarboxylating) (NADP+) (EC 1.1.1.40) or NADP-malic enzyme (NADP-ME) is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction in the presence of a bivalent metal ion:[1]

- (S)-malate + NADP+ pyruvate + CO2 + NADPH

| NADP-malic enzyme | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 1.1.1.40 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 9028-47-1 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Thus, the two substrates of this enzyme are (S)-malate and NADP+, whereas its 3 products are pyruvate, CO2, and NADPH. Malate is oxidized to pyruvate and CO2, and NADP+ is reduced to NADPH.

This enzyme belongs to the family of oxidoreductases, to be specific those acting on the CH-OH group of donor with NAD+ or NADP+ as acceptor. The systematic name of this enzyme class is (S)-malate:NADP+ oxidoreductase (oxaloacetate-decarboxylating). This enzyme participates in pyruvate metabolism and carbon fixation. NADP-malic enzyme is one of three decarboxylation enzymes used in the inorganic carbon concentrating mechanisms of C4 and CAM plants. The others are NAD-malic enzyme and PEP carboxykinase.[2][3] Although often one of the three photosynthetic decarboxylases predominate, the simultaneous operation of all three is also shown to exist.[4]

Enzyme structure

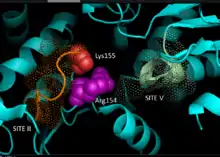

Based on crystallography data of homologous NADP-dependent malic enzymes of mammalian origin, a 3D model for C4 pathway NADP-ME in plants has been developed, identifying the key residues involved in substrate-binding or catalysis. Dinucleotide binding involves two glycine-rich GXGXXG motifs, a hydrophobic groove involving at least six amino acid residues, and a negatively charged residue at the end of the βB-strand.[5][6] The primary sequence of the first motif, 240GLGDLG245, is a consensus marker for phosphate binding, evidencing involvement with NADP binding, while the other glycine rich motif adopts a classical Rossmann fold—also a typical marker for NADP cofactor binding.[7] Mutagenesis experiments in maize NADP-ME have supported the current model.[1] Valine substitution for glycine in either motif region rendered the enzyme completely inactive while spectral analysis indicated no major changes from wild-type form. The data is suggestive of direct impairment at a key residue involved in binding or catalysis rather than an inter-domain residue influencing conformational stability. Additionally, a key arginine residue at site 237 has been shown to interact both with malate and NADP+ substrates, forming key favorable electrostatic interactions to the negatively charged carboxylic-acid and phosphate group respectively. Elucidation of whether the residue plays a role in substrate binding or substrate positioning for catalysis has yet to be determined.[8] Lysine residue 255 has been implicated as a catalytic base for the enzymes reactivity; however, further studies are still required to conclusively establish its biochemical role.[1]

Structural studies

As of 2007, 3 structures have been solved for this class of enzymes, with PDB accession codes 1GQ2, 1GZ4, and 2AW5.

Biological function

In a broader context, malic enzymes are found within a wide range of eukaryotic organisms, from fungi to mammals, and beyond that, are shown to localize in range of subcellular locations, including the cytosol, mitochondria, and chloroplast. C4 NADP-ME, specifically, is in plants localized in bundle sheath chloroplasts.[1]

During C4 photosynthesis, an evolved pathway to increase localized CO2 concentrations under the threat of enhanced photorespiration, CO2 is captured within mesophyll cells, fixed as oxaloacetate, converted into malate and released internally within bundle sheath cells to directly feed RuBisCO activity.[9] This release of fixed CO2, triggered by the favorable decarboxylation of malate into pyruvate, is mediated by NADP-dependent malic enzyme. In fact, the significance of NADP-ME activity in CO2 conservation is evidenced by a study performed with transgenic plants exhibiting a NADP-ME loss of function mutation. Plants with the mutation experienced 40% the activity of wild-type NADP-ME and achieved significantly reduced CO2 uptake even at high intercellular levels of CO2, evidencing the biological importance of NADP-ME at regulating carbon flux towards the Calvin cycle.[10][11]

Enzyme regulation

NADP-ME expression has been shown to be regulated by abiotic stress factors. For CAM plants, drought conditions cause stoma to largely remain shut to avoid water loss by evapotranspiration, which unfortunately leads to CO2 starvation. In compensation, closed stoma activates the translation of NADP-ME to reinforce high efficiency of CO2 assimilation during the brief intervals of CO2 intake, allowing for carbon fixation to continue.

In addition to regulation at the longer time scale by means of expression control, regulation at the short-time scale can occur through allosteric mechanisms. C4 NADP-ME has been shown to be partially inhibited by its substrate, malate, suggesting two independent binding sites: one at the active site and one at an allosteric site. However, the inhibitory effect exhibits pH-dependence – existent at a pH of 7 but not a pH of 8. The control of enzyme activity due to pH changes align with the hypothesis that NADP-ME is most active while photosynthesis is in progress: Active light reactions leads to a rise in basicity within the chloroplast stroma, the location of NADP-ME, leading to a diminished inhibitory effect of malate on NADP-ME and thereby promoting a more active state. Conversely, slowed light reactions leads to a rise in acidity within the stroma, promoting the inhibition of NADP-ME by malate. Because the high energy products of the light reactions, NADPH and ATP, are required for the Calvin cycle to proceed, a buildup of CO2 without them is not useful, explaining the need for the regulatory mechanism.[12]

This protein may use the morpheein model of allosteric regulation.[13]

Evolution

NADP-malic enzyme, as all other C4 decarboxylases, did not evolve de novo for CO2 pooling to aid RuBisCO.[14] Rather, NADP-ME was directly transformed from a C3 species in photosynthesis, and even earlier origins from an ancient cystolic ancestor. In the cytosol, the enzyme existed as a series of housekeeping isoforms purposed towards a variety of functions including malate level maintenance during hypoxia, microspore separation, and pathogen defense. In regards to the mechanism of evolution, the C4 functionality is thought to have stemmed from gene duplication error both within promoter regions, triggering overexpression in bundle-sheath cells, and within the coding region, generating neofunctionalization.[15] Selection for CO2 preservation function as well as enhanced water and nitrogen utilization under stressed conditions was then shaped by natural pressures.[16]

See also

- ME1 (human gene)

References

- Detarsio E, Wheeler MC, Campos Bermúdez VA, Andreo CS, Drincovich MF (April 2003). "Maize C4 NADP-malic enzyme. Expression in Escherichia coli and characterization of site-directed mutants at the putative nucleoside-binding sites". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (16): 13757–64. doi:10.1074/jbc.M212530200. PMID 12562758.

- Kanai, Ryuzi; Edwards, Gerald E. (1999). "The Biochemistry of C4 Photosynthesis". In Sage, Rowan F.; Monson, Russell K. (eds.). C4 Plant Biology. Academic Press. pp. 49–87. ISBN 978-0-08-052839-7.

- Christopher JT, Holtum J (September 1996). "Patterns of Carbon Partitioning in Leaves of Crassulacean Acid Metabolism Species during Deacidification". Plant Physiology. 112 (1): 393–399. doi:10.1104/pp.112.1.393. PMC 157961. PMID 12226397.

- Furumoto T, Hata S, Izui K (October 1999). "cDNA cloning and characterization of maize phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, a bundle sheath cell-specific enzyme". Plant Molecular Biology. 41 (3): 301–11. doi:10.1023/A:1006317120460. PMID 10598098. S2CID 8302572.

- Rossman, Michael G.; Liljas, Anders; Brändén, Carl-Ivar; Banaszak, Leonard J. (1975). "Evolutionary and Structural Relationships among Dehydrogenases". In Boyer, Paul D. (ed.). The Enzymes. Vol. 11. pp. 61–102. doi:10.1016/S1874-6047(08)60210-3. ISBN 978-0-12-122711-1.

- Bellamacina CR (September 1996). "The nicotinamide dinucleotide binding motif: a comparison of nucleotide binding proteins". FASEB Journal. 10 (11): 1257–69. doi:10.1096/fasebj.10.11.8836039. PMID 8836039.

- Rothermel BA, Nelson T (November 1989). "Primary structure of the maize NADP-dependent malic enzyme". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 264 (33): 19587–92. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)47154-8. PMID 2584183.

- Coleman, David E.; Rao, G. S. Jagannatha; Goldsmith, E. J.; Cook, Paul F.; Harris, Ben G. (June 2002). "Crystal Structure of the Malic Enzyme from Ascaris suum Complexed with Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide at 2.3 Å Resolution". Biochemistry. 41 (22): 6928–38. doi:10.1021/bi0255120. PMID 12033925.

- Edwards GE, Franceschi VR, Voznesenskaya EV (2004). "Single-cell C(4) photosynthesis versus the dual-cell (Kranz) paradigm". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 55: 173–96. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141725. PMID 15377218.

- Pengelly JJ, Tan J, Furbank RT, von Caemmerer S (October 2012). "Antisense reduction of NADP-malic enzyme in Flaveria bidentis reduces flow of CO2 through the C4 cycle". Plant Physiology. 160 (2): 1070–80. doi:10.1104/pp.112.203240. PMC 3461530. PMID 22846191.

- Rathnam CK (January 1979). "Metabolic regulation of carbon flux during C4 photosynthesis : II. In situ evidence for reffixation of photorespiratory CO2 by C 4 phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase". Planta. 145 (1): 13–23. doi:10.1007/BF00379923. PMID 24317560. S2CID 22462853.

- Saigo M, Tronconi MA, Gerrard Wheeler MC, Alvarez CE, Drincovich MF, Andreo CS (November 2013). "Biochemical approaches to C4 photosynthesis evolution studies: the case of malic enzymes decarboxylases". Photosynthesis Research. 117 (1–3): 177–87. doi:10.1007/s11120-013-9879-1. hdl:11336/7831. PMID 23832612. S2CID 17803651.

- Selwood T, Jaffe EK (March 2012). "Dynamic dissociating homo-oligomers and the control of protein function". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 519 (2): 131–43. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2011.11.020. PMC 3298769. PMID 22182754.

- Maier A, Zell MB, Maurino VG (May 2011). "Malate decarboxylases: evolution and roles of NAD(P)-ME isoforms in species performing C(4) and C(3) photosynthesis". Journal of Experimental Botany. 62 (9): 3061–9. doi:10.1093/jxb/err024. PMID 21459769.

- Monson, Russell K. (May 2003). "Gene Duplication, Neofunctionalization, and the Evolution of C4 Photosynthesis". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 164 (S3): S43–S54. doi:10.1086/368400. S2CID 84685191. INIST:14976375.

- Drincovich MF, Casati P, Andreo CS (February 2001). "NADP-malic enzyme from plants: a ubiquitous enzyme involved in different metabolic pathways". FEBS Letters. 490 (1–2): 1–6. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(00)02331-0. PMID 11172800. S2CID 31317255.

Further reading

- Harary, Isaac; Korey, Saul R.; Ochoa, Severo (August 1953). "Biosynthesis of dicarboxylic acids by carbon dioxide fixation. VII. Equilibrium of malic enzyme reaction". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 203 (2): 595–604. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)52329-8. PMID 13084629.

- Ochoa S, Mehler AH, Kornberg A (July 1948). "Biosynthesis of dicarboxylic acids by carbon dioxide fixation; isolation and properties of an enzyme from pigeon liver catalyzing the reversible oxidative decarboxylation of 1-malic acid". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 174 (3): 979–1000. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)57307-5. PMID 18871257.

- Rutter WJ, Lardy HA (August 1958). "Purification and properties of pigeon liver malic enzyme". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 233 (2): 374–82. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64768-4. PMID 13563505.

- Stickland RG (December 1959). "Some properties of the malic enzyme of pigeon liver. 1. Conversion of malate into pyruvate". The Biochemical Journal. 73 (4): 646–54. doi:10.1042/bj0730646. PMC 1197115. PMID 13834656.

- Stickland RG (December 1959). "Some properties of the malic enzyme of pigeon liver. 2. Synthesis of malate from pyruvate". The Biochemical Journal. 73 (4): 654–9. doi:10.1042/bj0730654. PMC 1197116. PMID 13834657.

- Walker DA (February 1960). "Physiological studies on acid metabolism. 7. Malic enzyme from Kalanchoe crenata: effects of carbon dioxide concentration". The Biochemical Journal. 74 (2): 216–23. doi:10.1042/bj0740216. PMC 1204145. PMID 13842495.