New England Revolution

The New England Revolution is an American professional soccer club based in the Greater Boston area that competes in Major League Soccer (MLS), in the Eastern Conference of the league. It is one of the ten charter clubs of MLS, having competed in the league since its inaugural season.

_logo.svg.png.webp) | |||

| Full name | New England Revolution | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | The Revs | ||

| Founded | June 6, 1995 | ||

| Stadium | Gillette Stadium | ||

| Capacity | 20,000[note 1] | ||

| Owner | Robert Kraft | ||

| President | Brian Bilello | ||

| Head Coach | Clint Peay (interim) | ||

| League | Major League Soccer | ||

| 2023 | Eastern Conference: 5th Overall: 6th Playoffs: TBD | ||

| Website | Club website | ||

|

| |||

The club is owned by Robert Kraft, who also owns the New England Patriots along with his son, Jonathan Kraft. The name "Revolution" refers to the New England region's significant involvement in the American Revolution that took place from 1775 to 1783.

New England plays their home matches at Gillette Stadium in Foxborough, Massachusetts, located 21 miles (34 km) southwest of downtown Boston. The club played their home games at the adjacent and now-demolished Foxboro Stadium, from 1996 until 2001. The Revs are the only original MLS team to have every league game in their history televised.[1]

The Revolution won their first major trophy in the 2007 U.S. Open Cup. The following year, they won the 2008 North American SuperLiga. They won their first Supporters' Shield in 2021.[2] The Revolution have participated in five MLS Cup finals in 2002, 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2014, which are the most of clubs who have not won the MLS Cup.

History

The early years (1996–2001)

Soccer has a long history in the New England region. In 1862, the Oneida Football Club in Boston was the first organized team to play any kind of "football/soccer" in the United States. In the 1920s, the Boston Soccer Club (later renamed the Bears) and Fall River F.C. were formed and played in the professional American Soccer League, which comprised teams based in the Northeastern U.S. region. The 'Marksmen' were one of the most successful soccer clubs in the United States, winning the National Challenge Cup four times. At the inaugural FIFA World Cup in 1930 in Uruguay, Bert Patenaude (from Fall River, Massachusetts) scored the first hat-trick in World Cup play.[3] The USMNT finished in third place.[4] The Boston area was next represented by the New England Tea Men (1978–80) and Boston Minutemen (1974–76), who played in the FIFA-backed, major professional North American Soccer League (NASL). However, each club struggled for financial solvency and folded.[5] The NASL folded in 1984, leaving the United States without a top-level soccer league until Major League Soccer (MLS) began play in 1996.[6]

The success of the 1994 FIFA World Cup (with Foxboro Stadium as one of nine venues) paved the way for a new era of sports in the Boston area and to bring professional soccer back to the region. On June 6, 1995, Robert Kraft became the founding investor/operator of the Revolution, joining Major League Soccer (MLS) as one of its 10 charter clubs for its inaugural season in 1996.[7] Kraft is also the owner of the National Football League's (NFL) New England Patriots and CEO of the Kraft Group.[8]

The inaugural Revolution team featured several U.S. Men's national team regulars returning from abroad to be part of the new league. Despite the presence of Alexi Lalas, Mike Burns, and Joe-Max Moore, however, the team was one of only two that failed to make the playoffs of the then 10 team league. The following season, the squad made the playoffs, but failed to advance past the first round. For the next five years, this playoff result would be the Revs' best (which they matched in the 2000 season), as a revolving door of players and head coaches failed to make much of an impact on the fledgling league.

Attendance in these early years was high despite the team's poor on-field performances. More than 15,000 people per match regularly came to watch the Revolution play in the old Foxboro Stadium in Foxborough, Massachusetts. The Revs did manage to make the final of the 2001 U.S. Open Cup, but they lost to the Los Angeles Galaxy on a golden goal by Danny Califf. It was a harbinger of finals to come for the Revolution.

Steve Nicol era (2002–2011)

Liverpool great Steve Nicol was appointed as head coach on a full-time basis during the 2002 season. He had previously held the position of interim head coach during the 1999 and 2002 seasons. After taking over, Nicol guided the Revolution to a playoff berth for a league-record eight straight seasons, failing for the first time in 2010. The first six of those berths (from 2002 to 2007) resulted in an appearance in the conference final or better, including three consecutive MLS Cup finals from 2005 to 2007. From the 2008 season until 2013, the Revs failed to go further than the first round of the playoffs. Still, Nicol was respected as one of the best coaches in the league.[9][10]

Playoff success (2002–2007)

In his first season in charge, Nicol guided the Revs to a first-place finish in the Eastern Conference. The team advanced through the playoffs to the MLS Cup final, where they lost to the Galaxy again, this time 1–0 on a golden goal by Carlos Ruiz. Held at Gillette Stadium, the Cup final was attended by 61,316 spectators, the largest figure for any MLS Cup until 2018.

Consecutive MLS Cup finals

After losing in the conference finals in 2003 and 2004, the Revs repeated their 2002 feat finishing tops in the east and losing the cup final to Los Angeles 1–0 in extra time again in 2005. New England had a real chance to win their first MLS championship, in MLS Cup 2006, against the Houston Dynamo. After Taylor Twellman scored in the 113th minute, the Revs allowed an equalizing header from the Dynamo's Brian Ching less than a minute later that sent the game to penalty kicks, where the Revs lost 4–3.

In the 2007 season, the Revs made it to two cup finals. The 2007 MLS Cup was a rematch from the previous year, though the result was the same as Houston defeated New England 2–1.[11] The Revolution hold the record for most losses in MLS Cup games. Though they lost the 2007 MLS Cup, they defeated FC Dallas 3–2 to win their first-ever trophy: the 2007 U.S. Open Cup.

Their 2002 MLS Cup appearance granted them a spot in the 2003 CONCACAF Champions Cup, but they lost their first match-up 5:3 on aggregate after playing two games on the road to LD Alajuelense. The Revolution again faced LD Alajuelense of Costa Rica in the home and away 2006 CONCACAF Champions' Cup. The "home" game was played February 22, 2006, in Bermuda despite some fans feeling that playing at Gillette Stadium in the adverse conditions of winter in New England could have been advantageous. The Revs failed to advance, as they drew 0–0 in Bermuda and lost 0–1 in Costa Rica.

Rebuilding (2008–2011)

The 2007 U.S. Open Cup victory qualified the club for the preliminary round of the newly expanded CONCACAF Champions League. Additionally, their top-four finish qualified them for SuperLiga 2008. Therefore, the Revolution competed in four different competitions (MLS, Open Cup, Champions League, and SuperLiga) during the 2008 season. The Revolution had an excellent run at the beginning of the 2008 season. By mid-July, they were leading the overall MLS table and had finished as the number one overall seed in SuperLiga. The team won the tournament, defeating the Houston Dynamo on penalties to earn a small amount of revenge on for their successive MLS Cup defeats. That trophy, however, was the high point for the 2008 Revs. Fixture congestion led to a rash of injuries and general fatigue, and the team crashed out the Champions League with an embarrassing 4–0 home defeat to regional minnows Joe Public FC of Trinidad and Tobago (the tie ended 6–1 Joe Public on aggregate). The team also struggled in domestic play, limping to a third-place finish in the East and losing to the Chicago Fire in the first round of the playoffs. The Revs managed a semifinal appearance in the 2008 U.S. Open Cup, but lost to D.C. United.

In 2009, the Revs continued the mediocrity that had plagued the second half of their 2008 season, losing to Chicago again in the first round of the playoffs. The team also lost to Chicago in the semifinals of the 2009 SuperLiga. 2010 started even more dismally than 2009, with the team failing to put together an unbeaten streak longer than three games until July. Despite the abysmal progress, this unbeaten streak coincided with the Revs' third consecutive SuperLiga appearance, and for the second time in three years, the team made the competition's final, but lost 2–1 to Monarcas Morelia of Liga MX.

The team failed to make the playoffs in either 2010 or 2011, and at the end of the 2011 season, announced they had parted ways with manager Steve Nicol, who had managed the team for 10 years.

2010s

The team hired former player Jay Heaps as head coach. The 2012 season was another disappointment. In 2013, the team finished 3rd place in the Eastern Conference, making the playoffs for the first time since 2009 with the help of a budding Homegrown Player, Diego Fagundez, who grew up in Leominster, Massachusetts.[12]

In the April 2014 issue of Boston Magazine, journalist Kevin Alexander named the Kraft family as "the Worst Owners in the League" in an article that contrasted the family's sparkling reputation as NFL owners with their alleged lack of interest in MLS and the Revolution.[13] The 2014 season brought success. The Revolution signed U.S. national team member Jermaine Jones in late August on a designated player contract. They then went on a 10–1–1 streak led by Jones and MVP candidate Lee Nguyen to finish in 2nd place in the regular season in the Eastern Conference. The Revolution breezed through the playoffs without losing a game, making it to their first MLS Cup Final since 2007. New England lost 2–1 to the LA Galaxy, their lone goal scored by Chris Tierney, a native of Wellesley, Massachusetts. This marked the club's fifth MLS Cup loss in five MLS Cup Final appearances.

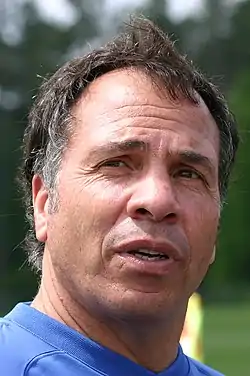

Bruce Arena era (2019–2023)

On May 9, 2019, coach Brad Friedel was fired by the Revolution after a 12–21–13 career record and a 2–8–2 record to open the 2019 season.[14] He was replaced by former D.C. United, LA Galaxy and USMNT coach Bruce Arena.[15] Under Arena, the Revolution went eleven games undefeated until losing 2–0 to the Los Angeles FC on August 3, 2019. They were eliminated in the 1st Round of the 2019 Playoffs by Atlanta United FC, getting shut out 1–0. The Revolution lost to the Columbus Crew 1–0 in the Eastern Conference Finals in the 2020 Playoffs. The Bruce Arena era ended on September 9, 2023, after Arena's resignation following a six-week investigation into insensitivity and inappropriate comments.

2021: Supporters' Shield winners

The 2021 season saw the Revolution win their first Supporters' Shield in club history by having the best record in the regular season.[16] New England set a new MLS record for points in a season (73), surpassing the previous mark of 72 set by Los Angeles FC in 2019.[17] Goalkeeper Matt Turner won the MLS Goalkeeper of the Year Award, and Carles Gil won the MLS Most Valuable Player Award. In the MLS Quarterfinals, the Revolution lost to eventual MLS Cup finalist, New York City FC on penalties, ending their hopes to be the first MLS team to complete the league double (winning both the Supporters' Shield and MLS Cup) since 2017.

The franchise's turnaround since May 2019 has been credited to head coach and sporting director Bruce Arena.[18]

Team colors and crest

The original club badge was stylized and based on the flag of the United States with some of the stars made into a soccer ball (similar to Adidas' ball for the UEFA Champions League), composed of six stars, representing the six New England states. The overall design mirrored the 1994 FIFA World Cup logo. The Revolution was the last founding team of the MLS to keep its original crest. In 2014, the flag and ball were retained while the name was dropped.

In 2021, the club launched its new logo. They enlisted an independent third-party to conduct focus groups consisting of Boston sports fans to elicit feedback about what the re-branded badge should represent.[19] It features an "R" sitting above a red strikethrough. The inner shape references traditional flag drapery which plays homage to the original Revolution logo. The "R"'s font references the Boston Tea Party mark and American Revolutionary era lettering. Red details around the logo itself are reminiscent of patriotic bunting and the strikethrough behind the logo is meant to symbolize defiance.[20]

Uniforms

Traditionally, the Revolution have worn all-navy at home, with the exception of red shorts during the club's first year in 1996. Since 2014, the club has worn white shorts at home. To mark the club and the league's 25th anniversary, the red shorts returned for the 2020 and 2021 seasons. The Revolution wore white secondary uniforms for their entire existence until 2015; that year club introduced a red away jersey with white and green accents in tribute to the flag of New England, and away uniforms demonstrated more design variation from there. The following is a partial list of the last nine kits worn by the Revolution.

- Home

2006–2007

|

2008–2009

|

2010–2011

|

2012–2013

|

2014–2015

|

2016–2017

|

2018–2019

|

2020–2021

|

2022–

|

- Away

2006–2007

|

2008–2009

|

2010–2011

|

2012–2014

|

2015–2016

|

2017–2018

|

2019–2020

|

2021–2022

|

2023-

|

Stadium

.jpg.webp)

The Revolution play home matches at Gillette Stadium in Foxborough, Massachusetts. At its inception, the Revolution played their games at Foxboro Stadium, alongside the American football team New England Patriots of the National Football League (NFL). In 2002, Robert Kraft financed a $350-million project as a replacement for Foxboro Stadium which would come to be known as Gillette Stadium.[21] In 2007, Kraft began to develop the land around Gillette Stadium, creating a $375-million open-air shopping and entertainment center called Patriot Place.[22][23]

Gillette Stadium is a 66,000-seat stadium including luxury and box seating.[24] The Revolution artificially limit the stadium's capacity for MLS matches, with certain seating sections covered with tarpaulins, or made inaccessible. However, the club does open the entire stadium for international matches and MLS Playoffs. On October 20, 2002, during the 2002 MLS Cup final a record was established when a crowd of 61,316 attended a Revolution 1–0 loss against the Los Angeles Galaxy. This was the largest stand-alone MLS post-season crowd on record until the 2018 MLS Cup in Atlanta at Mercedes-Benz Stadium.[25]

Although the Revolution have played on natural grass from 2002 to 2006, they currently play on FieldTurf which was upgraded in April 2014 to FieldTurf "Revolution" with "VersaTile" drainage system. Gillete Stadium's FieldTurf surface was certified by FIFA with a two-star quality rating, the highest possible rating.[26] Kraft, however, announced that he would be willing to switch the stadium to a natural grass playing field as part of his stadium bid for 2026 FIFA World Cup.[27]

Kraft opened a new $35 million training center in 2019. The team's training facilities and offices are located in the wetlands behind Gillette Stadium. Despite these new facilities, Kraft claimed that he was still committed to building a new soccer-specific stadium closer to the city limits of Boston.[28]

Plans for a soccer–specific stadium

On August 2, 2007, The Boston Herald reported that the city of Somerville and Revolution officials had held preliminary discussions about building a 50,000 to 55,000-seat stadium on a 100-acre (0.40 km2) site off of Innerbelt Road near Interstate 93 In the Inner Belt / Brickbottom area. The stadium could cost anywhere between $50 and $200 million based on other similar MLS soccer-specific stadiums.[29]

Additionally in 2007, then-Boston mayor Tom Menino wrote to MLS suggesting Roxbury, Boston's "Parcel 3," across from Boston Police Headquarters, be considered as a spot for a Revolution stadium. However, according to a 2007 Boston Globe editorial, the task force promised to investigate the site was never formed.[30]

In a July 2010 interview, Kraft said that over $1 million had been invested in finding a suitable site, preferably in the urban core.[31]

After a two-year hiatus, the Revolution renewed their plans to build a stadium in Somerville since the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority finalized its Green Line maintenance facility plans.[32] The team was this time focused on Assembly Row, and Somerville mayor Joseph Curtatone confirmed to the Somerville Journal that he'd been in contact with the team for months regarding the site.[33][34]

In 2012, Revere Mayor Dan Rizzo expressed an interest in the Revolution building a stadium in Revere.[35] The Boston Globe reported on October 1, 2012 that the Revolution had held talks with the Mayor regarding building a stadium at the Wonderland Greyhound Park property if the city was able to acquire it as part of casino negotiations surrounding Suffolk Downs.[36] Revere eventually lost the casino bid to Everett.[37]

On October 16, 2012, Fall River, Massachusetts Mayor William Flanagan wrote a letter to Kraft pitching Fall River as a potential site for a Revolution, focusing on the city's "strong soccer culture," Flanagan invited Kraft to take a tour.[38] Revolution spokesman Jeff Cournoyer stated to The Enterprise regarding the proposal that “there has been significant interest and we’ve been contacted by several communities. We will continue to vet all opportunities."[39]

On July 1, 2014, WPRI-TV reported that then-Providence Mayor Angel Taveras confirmed that the city had preliminary discussions with officials from the Revolution surrounding a stadium, and that then-Central Falls Mayor James Diossa had spoken to president Brian Bilello about a move to Central Falls.[40]

On November 18, 2014, The Boston Globe reported that the Kraft family had met with city and state officials over a stadium in South Boston on a public lot off Interstate 93 on Frontage Road near Widett Circle.[41] The proposed site is adjacent to an industrial site that has been identified for the main Olympic stadium by the organizing group for Boston's now-failed bid to host the 2024 Summer Olympics, of which Robert Kraft was a member.[42]

On April 28, 2017, Associated Press reported that talks between the Kraft Group and University of Massachusetts Boston over a proposed stadium location in Dorchester, Boston at South Boston's Bayside Expo Center had ended. Talks had been ongoing since June 2016, but politicians were concerned over the rise in traffic a stadium would bring.[43]

In 2019, The Providence Journal reported that 2017 conversations between Jonathan Kraft and then-Rhode Island governor Gina Raimondo led to Rhode Island's Commerce Corporation assigning Boston design firm Utile to find suitable spots for a Revolution stadium in Rhode Island. The group ultimately identified The "Tockwotton" waterfront in East Providence, Rhode Island, The Port of Providence waterfront off Allens Avenue, The "Tidewater" property on the Seekonk River in Pawtucket, and The Apex building site near Slater Mill Historic Site as suitable.[44]

On March 17, 2022, Boston.com reported that the Revolution may be interested in building a stadium at the site of the old Mystic Generating Station in Everett, Massachusetts, next to Encore Boston Harbor casino, after its acquisition by Wynn Resorts.[45] On July 15, 2022, The Boston Globe reported that The Massachusetts House of Representatives had passed legislation that could potentially allow the Revolution to build a stadium on said property by exempting the 43-acre parcel of land from environmental requirements.[46] The Boston Globe reported on August 1, 2022 that the bill containing this legislation did not pass.[47]

Player development

Reserves

On October 9, 2019, the club announced the formation of a reserve team, New England Revolution II, in USL League One that would begin play in the 2020 season and that they would play at Gillette Stadium in Foxborough.[48] On November 25, 2019, the club announced its first manager, Clint Peay.[49]

The club announced on December 6, 2021, that it was joining the inaugural 21-team MLS Next Pro season starting in 2022.[50]

Academy system

The New England Revolution Academy is an elite youth development program fully-funded by the senior club and recognized by U.S. Soccer as one of the top 10 youth development programs in the country.[51][52] Competing in MLS Next, a successor to the U.S. Soccer Development Academy, the Revolution Academy provides local players throughout Greater Boston and beyond (regardless of their financial situation) a pathway to a professional career.

All Revolution youth team home matches are played at Gillette Stadium. However, due to scheduling conflicts, some home matches in the past have been hosted at the B.M.C. Durfee High School in Fall River, Massachusetts, and the Fruit Street Fields (located in Hopkinton, Massachusetts).[53]

Since 2010 when Diego Fagúndez became the Revolution's first ever MLS Homegrown Player Rule signing, the Revolution have promoted several other youth prospects from their academy team, including Scott Caldwell, Zachary Herivaux, Justin Rennicks, Noel Buck, Esmir Bajraktarević, and Damian Rivera.[54][55]

Club culture

Supporters

.svg.png.webp)

_(9533446637).jpg.webp)

The team's supporter's clubs are called the "Midnight Riders" and "The Rebellion".[57] The name 'Midnight Riders' is in honor of the famous rides of Paul Revere and William Dawes, who announced the departure of British troops from Boston to Concord at the beginning of the American Revolution. The two groups together occupy the north stand of the stadium, which they have nicknamed "The Fort". The Fort is a general admission section and draws its name from the revolutionary theme which runs through the team supporters.[58] In the same theme, the Revolution also employ a corps known as the End Zone Militia, a group of American Revolutionary War reenactors founded in 1996 by Geoff Campbell. The reenactors wear authentic 18th century clothing including the iconic colonial tricorn hat, and carry flintlock black gunpowder muskets which are ceremoniously fired when the Revolution score a goal.[59]

Rivalries

The club's main rival is widely considered to be New York Red Bulls,[60] due to the rivalry stemming from other Boston–New York rivalries in other professional sports such as the Knicks–Celtics rivalry in the NBA, the Jets–Patriots rivalry in the NFL and the Yankees-Red Sox rivalry in Major League Baseball. Beginning in 2002, the Revs had a 20 match undefeated streak against the Red Bulls for games at Gillette Stadium. This streak helped to intensify the rivalry between the teams. The streak came to an end on June 8, 2014, as the Red Bulls won 2–0 at Gillette Stadium.[61]

The Revolution have also built rivalries with fellow Eastern Conference teams D.C. United and Chicago Fire.[62] These teams have faced each other on numerous occasions in the playoffs. In a 2009 poll on the club's official site, New England fans considered the Chicago Fire the Revs' most bitter rival as the clubs have clashed many times in the MLS playoffs and regular season.[63]

Since 2015 a rivalry has also developed with newcomer club New York City FC, due to the latter club's association with the Yankees and with Yankee Stadium being the club's incumbent home ground. To further fuel this rivalry, New York City FC knocked out the Revolution in the eastern conference semifinals of the 2021 MLS Cup Playoffs in a 2–2 tie that eventually went to penalties, despite the Revolution having the superior regular season record that year.

Broadcasting

From 2021 to 2022, all Revolution matches were televised locally in high definition on either WBZ-TV or WSBK-TV; nationally televised matches aired on ESPN, Fox Sports, and Univision. All matches are broadcast on radio by 98.5 The Sports Hub, but this is a simulcast of the TV feed. Brad Feldman served as the team's longtime play-by-play on both TV and radio, with former Revolution and USMNT player Charlie Davies doing color commentary.[64] Prior to 2021, matches were aired locally on NBC Sports Boston.[65]

With every MLS game available on Apple TV via their rights deal in 2023, Revolution games will be broadcast almost exclusively on this service, with exceptions for certain national linear television broadcast partners.

Players

Roster

- As of August 26, 2023[66]

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Out on loan

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

Team management

Head coaches

The interim head coach is Clint Peay, who took over from interim appointment Richie Williams. Bruce Arena helmed the club from 2019 until resigning in 2023 as a result of an investigation into misconduct.[67] Previously, Mike Lapper was the interim replacement for Brad Friedel, who was appointed the position in 2017 and subsequently fired in 2019.[68] There have been eight permanent managers and six interim managers of the Revolution since the appointment of the club's first professional manager, Frank Stapleton in 1996. The club's longest-serving head coach, in terms of both length of tenure and number of games overseen, is Steve Nicol, who managed the club between 2002 and 2011.[69]

Staff

| Ownership and senior management | |

|---|---|

| Owner | Robert Kraft |

| President | Brian Bilello |

| Technical director & Interim sporting director | Curt Onalfo |

| Coaching staff | |

| Head coach | |

| Assistant coach | |

| Assistant coach | |

| Director of goalkeeping | |

| Director of youth development | |

Honors

Continental trophies

- North American SuperLiga

- Champions: 2008

Domestic trophies

- Supporters' Shield

- Champions: 2021

- U.S. Open Cup

- Champions: 2007

- MLS Eastern Conference Championship

Individual club awards

Team records

Year-by-year

| Season | League | Position | Playoffs | USOC | Continental / Other | Average attendance |

Top goalscorer(s) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Div | League | Pld | W | L | D | GF | GA | GD | Pts | PPG | Conf. | Overall | Name(s) | Goals | ||||||

| 2017 | MLS | 1 | 34 | 13 | 15 | 6 | 53 | 61 | −8 | 45 | 1.32 | 7th | 15th | DNQ | QF | DNQ | 19,367 | 12 | ||

| 2018 | MLS | 34 | 10 | 13 | 11 | 49 | 55 | −6 | 41 | 1.21 | 8th | 16th | R4 | 18,347 | 11 | |||||

| 2019 | MLS | 34 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 50 | 57 | −7 | 45 | 1.32 | 7th | 14th | R1 | Ro16 | 16,737 | 10 | ||||

| 2020 | MLS | 23 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 26 | 25 | +1 | 32 | 1.39 | 8th | 15th | SF | NH | MLS is Back Tournament | Ro16 | 15,289 | 8 | ||

| 2021 | MLS | 34 | 22 | 5 | 7 | 65 | 41 | +24 | 73 | 2.15 | 1st | 1st | QF | NH | DNQ | 21,947 | 17[70] | |||

| 2022 | MLS | 34 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 47 | 50 | −3 | 48 | 1.41 | 10th | 20th | DNQ | Ro16 | CONCACAF Champions League | QF | 21,221 | 11 | ||

^ 1. Avg. attendance include statistics from league matches only.

^ 2. Top goalscorer(s) includes all goals scored in League, MLS Cup Playoffs, U.S. Open Cup, MLS is Back Tournament, CONCACAF Champions League, FIFA Club World Cup, and other competitive continental matches.

Notes

- Expandable to 65,878.

References

- "Revolution announces TV and radio schedule for 2006". March 14, 2006. Archived from the original on June 20, 2010. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- Le Miere, Jason (October 23, 2021). "New England Revolution win 2021 MLS Supporters' Shield". MLSsoccer.com. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- Williams, Jack (July 19, 2015). "Bert Patenaude, the forgotten hero who scored the first ever World Cup hat-trick". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- "Timeline". Archived from the original on July 21, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- McAdam, Sean (April 3, 2018). Boston: America's Best Sports Town. North Star Editions. ISBN 9781634940283. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- Lewis, Michael (October 20, 2018). "How the birth and death of the NASL changed soccer in America forever". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 28, 2022. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- "New England Revolution". Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- "New England Patriots". Archived from the original on September 30, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- Biglin, Mike (November 16, 2007). "MLS Cup 2007: Formula for success". Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- Madaio, Bob (February 3, 2010). "The New England Revolution's Steve and Shalrie Show". Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- "Dynamo beat Revolution 2–1 to repeat as MLS champions". Fox Sports. November 18, 2007. Archived from the original on November 20, 2007. Retrieved November 18, 2007.

- Bird, Hayden. "Diego Fagundez leaves a lasting legacy with the Revolution Academy". Boston.com. Archived from the original on April 30, 2023. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- Alexander, Kevin (March 25, 2014). "The Krafts Are the Worst Owners in the League". Archived from the original on March 27, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- "Brad Friedel relieved of duties as New England Revolution head coach | New England Revolution". Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- "Revolution name Bruce Arena new head coach, sporting director". RSN. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- Le Miere, Jason (October 23, 2021). "New England Revolution win 2021 MLS Supporters' Shield". Major League Soccer. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- "Recap | Revs set MLS record for most points in a season (73) with 1-0 victory over Rapids | New England Revolution". revolutionsoccer.net. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- ""What a ****show I inherited": How Bruce Arena transformed the New England Revolution". MLS. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- "New England Revolution unveil new crest | MLSSoccer.com". mlssoccer. Archived from the original on December 8, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- "New England Revolution unveil new crest and brand identity for 2022 and beyond". RevolutionSoccer.net (Press release). November 4, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- Olster, Scott (November 3, 2010). "Football's true Patriot". Fortune. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- Quinn, Kevin G. (2011). The Economics of the National Football League: The State of the Art. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 130. ISBN 9781441962898. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- O'Connell, James C. (2013). The Hub's Metropolis: Greater Boston's Development from Railroad Suburbs to Smart Growth. MIT Press. p. 244. ISBN 9780262018753. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- "Stadium Overview - Gillette Stadium". Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- "2018 MLS Cup in Atlanta shatters previous MLS Cup attendance record". www.mlssoccer.com. Archived from the original on January 17, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- "Gillette Stadium's Fieldturf Surface Achieves FIFA 2-Star Certification For The 2nd Consecutive Year". September 28, 2011. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- "Report: Robert Kraft Willing To Shift Gillette Stadium Back To Natural Grass For World Cup". September 15, 2021. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- "New England Revolution see new training center as 'game-changer'". December 19, 2019. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2006. Major League Soccer Communications (June 14, 2006). "Major League Soccer to seek proposals in New England for soccer-specific stadium sites". MLSnet.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2007.

- Scott Van Voorhis (August 2, 2007). "Revolution's the goal: Somerville talks stadium with Krafts". Boston Herald. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- Vaccaro, Adam (June 22, 2016). "5 places Bob Kraft has tried to build a soccer stadium". boston.com. The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 7, 2007.

- Eric Moskowitz (June 18, 2010). "Kick-start for team, city". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- Andrew Slevison (June 29, 2010). "Revs relaunched Somerville stadium plans". Tribal Football. Archived from the original on July 11, 2010. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- Vaccaro, Adam (October 17, 2012). "A Soccer Stadium For Somerville". scoutsomerville.com. Archived from the original on June 27, 2016. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- Guha, Auditi (October 11, 2012). "Somerville officials lukewarm on possible Revolution stadium". wickedlocal.com. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- Stoehr, Steve (October 2, 2012). "Revere Mayor Dan Rizzo Talks Revolution At Revere On Fox". thebentmusket.com. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- "Wonderland Greyhound Park property for the city in his casino negotiations with nearby Suffolk Downs". bostonglobe.com. The Boston Globe. October 1, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- Quinn, Garrett (September 16, 2014). "Suffolk Downs, Mohegan Sun dejected after losing casino to Wynn Resorts project in Everett, horse track likely to close". masslive.com. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- "Fall River Mayor Makes Appeal To Kraft For Revolution Stadium". www.wbur.org. October 16, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- Richmond, Will (October 17, 2012). "Mayor invites New England Revolution to move to Fall River". www.enterprisenews.com. The Enterprise. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- "Officials want New England Revolution to move to RI". July 1, 2014. Archived from the original on July 8, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- Bonn, Kyle (November 18, 2014). "Report: Kraft family has a site for a Revolution stadium in mind". NBC Sports. Archived from the original on January 26, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- Casey, Ross; Callum Borchers; Mark Arsenault (November 18, 2014). "Kraft family looks to build soccer stadium in Boston". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on November 21, 2014. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- Johnson, O'Ryan (April 28, 2017). "Talks cease for Kraft soccer stadium at Bayside Expo Center site". apnews.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- Anderson, Patrick (May 26, 2019). "Some R.I. officials are game for a soccer franchise". www.providencejournal.com. DallasNews Corporation. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- Chesto, John (March 17, 2022). "Wynn Resorts buys Everett power plant site. Is a Revs stadium on the Mystic next?". boston.com. The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- Stout, Matt; Estes, Andrea (July 15, 2022). "Mass. lawmakers have cleared the way for Robert Kraft to build a new soccer stadium for the New England Revolution in Everett". bostonglobe.com. The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- Chesto, Jon (August 1, 2022). "'We have urgent needs': Business leaders are frustrated as lawmakers fail to pass jobs bill". bostonglobe.com. The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- DePrisco, Michael (October 9, 2019). "Revolution launch USL League One Team, Revolution II, to begin play in 2020". NBC Sports Boston. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- "Clint Peay hired as inaugural head coach of Revolution II" (Press release). New England Revolution. November 25, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- "MLS NEXT Pro Unveils 21 Clubs for Inaugural Season". revolutionsoccer.

- "New England Revolution". revolutionsoccer.net. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- "New England Revolution". revolutionsoccer.net. Archived from the original on December 1, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- "New England Revolution". revolutionsoccer.net. Archived from the original on May 21, 2022. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- "Revolution Sign Midfielder Damian Rivera as a Homegrown Player". New England Revolution. Archived from the original on December 17, 2021. Retrieved December 17, 2021.

- "Revolution Sign Homegrown Player Isaac Angking". New England Revolution. Archived from the original on December 17, 2021. Retrieved December 17, 2021.

- "The Flag of New England | New England Revolution". Archived from the original on January 19, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- "Supporters Groups". Archived from the original on November 20, 2014. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- Joyce Furia (February 7, 2006). "Meet the Coach, Meet the Midnight Riders". Soccer New England.

- The Patriot Act: A Look at the End Zone Militia by Lauren Spencer Archived August 5, 2020, at the Wayback Machine New England Patriots

- "Revs, Red Bull renew I-95 rivalry". Fox News. The Sports Network. April 19, 2013. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- "Lloyd Sam equalizes for Red Bulls". ESPN. Associated Press. May 11, 2013. Archived from the original on December 15, 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- "Preview: Busy week wraps up on Saturday night as Revs host old rival D.C. United". April 21, 2017. Archived from the original on July 13, 2018. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- "Who is the true arch rival?". Archived from the original on October 17, 2014.

- "CBS Boston Is Now Your Home For New England Revolution Soccer". April 8, 2021. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- "Revs new TV home is Comcast SportsNet". March 15, 2010. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- "New England Revolution Roster". Major League Soccer. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- mlssoccer. "New England Revolution make another coach change after Bruce Arena's exit | MLSSoccer.com". mlssoccer. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- "Brad Friedel relieved of duties as New England Revolution head coach | New England Revolution". revolutionsoccer.net. Archived from the original on December 25, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- "New England Revolution - Manager history". worldfootball.net. Archived from the original on December 17, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- "Adam Buksa | MLSsoccer.com". mlssoccer. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

.svg.png.webp)