Name of France

The name France comes from Latin Francia ("land of the Franks").

Originally it applied to the whole Empire of the Franks, extending from southern France to eastern Germany. Modern France is still called Frankreich in German and similar names in some other Germanic languages (such as Frankrijk in Dutch), which means "Frank Reich", the Realm of the Franks.

Background

Gaul

Before being named France, the land was called Gaul (Latin: Gallia; French: Gaule). This name continued to be used even after the beginning of the reign of the Franks' Kings Clovis I, Charles Martel, Pepin the Short, and Charlemagne. In fact, for as long as the cultural elites of Europe used Latin predominantly, the name Gallia continued to be used alongside the name France. In English usage, the words Gaul and Gaulish are used synonymously with Latin Gallia, Gallus and Gallicus. However the similarity of the names is probably coincidental; the English words are borrowed from French Gaule and Gaulois, which appear to have been borrowed themselves from Germanic walha-, the usual word for the non-Germanic-speaking peoples (Celtic-speaking and Latin-speaking indiscriminately) and the source for Welsh in English. The Germanic w is regularly rendered as gu / g in French (cf. guerre = war, garder = ward, Guillaume = William), and the diphthong au is the regular outcome of al before a following consonant (cf. cheval ~ chevaux). Gaule or Gaulle can hardly be derived from Latin Gallia, since g would become j before a (cf. gamba > jambe), and the diphthong au would be incomprehensible; the regular outcome of Latin Gallia would have been * Jaille in French.[3][4]

Today, in modern French, the word Gaule is only used in a historical context. The only current use of the word is in the title of the leader of the French bishops, the archbishop of Lyon, whose official title is Primate of the Gauls (Primat des Gaules). Gaul is in the plural in the title, reflecting the three Gallic entities identified by the Romans (Celtica, Belgica, and Aquitania). The adjective gaulois (Gallic) is still sometimes used when a French person wants to stress some idiosyncrasies of the French people entrenched in history, such as nos ancêtres les Gaulois ("our ancestors the Gauls"), a phrase sometimes used in French when one wants to assert his own identity. During the Third Republic, the authorities often referred to notre vieille nation gauloise ("our old Gallic nation"), a case in which the adjective gaulois is used with a positive connotation. The word gallicisme is used sometimes in linguistic to express a specific form to the French language. In English, the word Gaul is never used in a modern context. The adjective Gallic is sometimes used to refer to French people, occasionally in a derisive and critical way, such as "Gallic pride". The Coq Gaulois (Gallic rooster in English) is also a national symbol of France, as for the French Football Federation. Astérix le Gaulois (Asterix, the Gaul) is a popular series of French comic books, following the exploits of a village of indomitable Gauls.

In Greek, France is still known as Γαλλία (Gallia). In Breton, meanwhile, the word Gall means "French",[1][2] and France is Bro C'hall[3] through Breton initial mutation; the second most common family name in Brittany is Le Gall, which is thought to indicate descendants of the inhabitants of Armorica from before the Bretons came from Britain, literally meaning "the Gaul".[4] The word can be used to refer to the French nationality, speakers of French and/or Gallo; an archaic word sense also indicated the generic "foreigner";[1][2] the derivative galleg means "French" as an adjective and the French language as a noun. In Irish, meanwhile, the term gall originally also referred to the inhabitants of Gaul, but in the ninth century it was repurposed as "generic foreigner" and used to refer to Scandinavian invaders; it was used later in the twelfth century for the Anglo-Normans.[5]

Francia

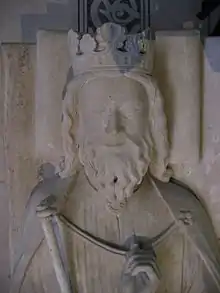

Under the reign of the Franks' Kings Clovis I, Charles Martel, Pepin the Short, and Charlemagne, a country that included most of modern France and modern Germany was known as Kingdom of Franks or Francia. At the Treaty of Verdun in 843, the Frankish Empire was divided in three parts: West Francia (Francia Occidentalis), Middle Francia and East Francia (Francia Orientalis).

The rulers of Francia Orientalis, who soon claimed the imperial title and wanted to reunify the Frankish Empire, dropped the name Francia Orientalis and called their realm the Holy Roman Empire (see History of Germany). The history of the Franconian Empire lives on today in place names such as Frankfurt or Franconia (Franken in German). The kings of Francia Occidentalis successfully opposed this claim and managed to preserve Francia Occidentalis as an independent kingdom, distinct from the Holy Roman Empire.

Since the name Francia Orientalis had disappeared, there arose the habit to refer to Francia Occidentalis as Francia only, from which the word France is derived. The French state has been in continuous existence since 843 (except for a brief interruption in 885–887), with an unbroken line of heads of states since the first king of Francia Occidentalis (Charles the Bald) to the current president of the French Republic (Emmanuel Macron). Notably, in German, France is still called Frankreich, which literally means "Reich (empire) of the Franks". In order to distinguish it from the Frankish Empire of Charlemagne, France is called Frankreich, while the Frankish Empire is called Frankenreich.

The name of the Franks itself is said to come from the Proto-Germanic word *frankon which means "javelin, lance". Another proposed etymology is that Frank means "the free men", based on the fact that the word frank meant "free" in the ancient Germanic languages. However, rather than the ethnic name of the Franks coming from the word frank ("free"), it is more probable that the word frank ("free") comes from the ethnic name of the Franks, the connection being that only the Franks, as the conquering class, had the status of freemen.

In a tradition going back to the 7th-century Chronicle of Fredegar, the name of the Franks itself is taken from Francio, one of the Germanic kings of Sicambri, c. 61 BCE, whose dominion extended all along those lands immediately joining the west-bank of the Rhine River, as far as Strasbourg and Belgium.[6] This nation is also explicitly mentioned by Julius Caesar in his Notebooks on the Gallic War (Commentarii de Bello Gallico).

The name of the former French currency, the franc, comes from the words engraved on the coins of the Frankish King, Rex Francorum, meaning "King of the Franks" or "Roi des Francs" in French.

France

In most of the Romance languages, France is known by the word "France" or any of its derivatives, for example Francia in Italian and Spanish. This is also the origin of its name in English, "France", which derived from Old French.

In most of the Germanic languages (though notably not in English), France is known as the historical "Land of the Franks", for example Frankreich (Reich of the Franks) in German, Frankrijk (Rijk of the Franks) in Dutch, Frankrike (Rike of the Franks) in Swedish and Norwegian, Frankrig in Danish.

Meanings of the name France

The name "France" (and its adjective "French") can have four different meanings which it is important to distinguish in order to avoid ambiguities. Its origin is the Germanic word "frank" which means "free" and is also a male name.

Political meaning

In a first meaning, "France" means the whole French Republic. In that case, "French" refers to the nationality, as it is written on the French ID card: "Nationalité : française".

The etymology and meaning of the word "France" and "French" have had strong bearings in the abolition of slavery and serfdom in France.

Indeed, in 1315, king Louis X issued an edict reaffirming that slavery was illegal in France by proclaiming that "France signifies freedom", that any slave setting foot on (metropolitan) French ground should be freed.[7]

Centuries later, this decree served as the basis for a group of crusading lawyers at the parlement of Paris, many of whom were members of the Society of the Friends of the Blacks, winning unprecedented emancipation rights in a series of cases before the French revolution, which (temporarily) led to the complete abolition of slavery on French overseas territories and colonies in 1794 [8] until Napoleon, propped up by the plantation lobbies, re-introduced slavery in sugarcane-growing colonies.[9]

Geographical meaning

In a second meaning, "France" refers to metropolitan France only, meaning mainland France.

Historical meanings

In a third meaning, "France" refers specifically to the province of the Île-de-France (with Paris at its centre) which historically was the heart of the royal demesne. This meaning is found in some geographic names, such as French Brie (Brie française) and French Vexin (Vexin français). French Brie, the area where the famous Brie cheese is produced, is the part of Brie that was annexed to the royal demesne, as opposed to Champagne Brie (Brie champenoise) which was annexed by Champagne. Likewise, French Vexin was the part of Vexin inside Île-de-France, as opposed to Norman Vexin (Vexin normand) which was inside Normandy.

In a fourth meaning, "France" refers only to the Pays de France, one of the several pays (Latin: pagi, singular pagus) of the Île-de-France. French provinces were typically made up of multiple pays, which were the direct continuation of the pagi set up by the Roman administration during Antiquity. The Île-de-France included the Pays de France, Parisis, Hurepoix, French Vexin, and others. The Pays de France is the fertile plain located immediately north of Paris which supported one of the most productive agriculture during the Middle Ages and helped to produce the tremendous wealth of the French royal court before the Hundred Years' War, making possible among other things the emergence of the Gothic art and architecture, which later spread all over western Europe. The Pays de France is also called the Plaine de France ("Plain of France"). Its historic main town is Saint-Denis, where the first Gothic cathedral in the world was built in the 12th century, and inside which the kings of France are buried. The Pays de France is now almost entirely built up as the northern extension of the Paris suburbs.

This fourth meaning is found in many place names, such as the town of Roissy-en-France, on whose territory is located Charles de Gaulle Airport. The name of the town literally means "Roissy in the Pays de France", and not "Roissy in the country France". Another example of the use of France in this meaning is the new Stade de France, which was built near Saint-Denis for the 1998 Football World Cup. It was decided to call the stadium after the Pays de France, to give it a local touch. In particular, the mayor of Saint-Denis made it very clear that he wanted the new stadium to be a stadium of the northern suburbs of Paris and not just a national stadium which happens to be located in the northern suburbs. The name is intended to reflect this, although few French people know this story and the great majority associates it with the country's name.

Other names for France

In Hebrew, France is called צרפת (Tzarfat). In Māori, France is known as Wīwī, derived from the French phrase oui, oui (yes, yes).[10]. In modern Greek, France is still known as Γαλλία (Gallia), derived from Gaul.

See also

References

- Walter, Henriette. "Les langues régionales de France : le gallo, pris comme dans un étau (17/20)". www.canalacademie.com. Canal Académie.

- Chevalier, Gwendal (2008), "Gallo et Breton, complémentarité ou concurrence?" [Gallo and Breton, complementarity or competition?], Cahiers de sociolinguistique (in French), no. 12, pp. 75–109, retrieved 2018-10-09

- Conroy, Joseph, and Joseph F. Conroy. Breton-English/English-Breton: dictionary and phrasebook. Hippocrene Books, 1997. Page 38.

- Favereau, Francis (2006). "Homophony and Breton Loss of Lexis". Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, 2006/2007, Vol. 26/27 (2006/2007), pp. 306-316. Page 311.

- Linehan, Peter; Janet L. Nelson (2003). The Medieval World. Vol. 10. Routledge. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-415-30234-0.

- David Solomon Ganz, Tzemach David, part 2, Warsaw 1859, p. 9b (Hebrew); Polish name of book: Cemach Dawid; cf. J.M. Wallace-Hadrill, Fredegar and the History of France, University of Manchester, n.d. pp. 536–538

- Miller, Christopher L. The French Atlantic triangle: literature and culture of the slave trade. Google Books. p. 20. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- David B. Gaspar, David P. Geggus, A Turbulent time: the French Revolution and the Greater Caribbean (1997) p. 60

- Hobhouse, Henry. Seeds of Change: Six Plants That Transformed Mankind, 2005. Page 111.

- Matras Y., Sakel J. Grammatical Borrowing In A Cross-Linguistic Perspective. 2007 p. 322.