Confederación Nacional del Trabajo

The Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (English: National Confederation of Labor; CNT) is a Spanish confederation of anarcho-syndicalist labor unions, which was long affiliated with the International Workers' Association (AIT). When working with the latter group it was also known as CNT-AIT. Historically, the CNT has also been affiliated with the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (English: Iberian Anarchist Federation); thus, it has also been referred to as the CNT-FAI. Throughout its history, it has played a major role in the Spanish labor movement.

National Confederation of Labor | |

Confederación Nacional del Trabajo | |

| |

| Predecessor | Solidaridad Obrera |

|---|---|

| Founded | 30 October – 1 November 1910 |

| Headquarters | Bilbao, Spain – location changes with the secretary general |

| Location |

|

Key people | Antonio Díaz García, secretary general |

| Affiliations | International Workers' Association |

| Website | www.cnt.es |

| Part of a series on |

| Anarcho-syndicalism |

|---|

|

Founded in 1910 in Barcelona[1] from groups brought together by the trade union Solidaridad Obrera, it significantly expanded the role of anarchism in Spain, which can be traced to the creation of the Spanish chapter of the IWA in 1870 and its successor organization, the Federation of Workers of the Spanish Region.

Despite several decades when the organization was illegal in Spain, today the CNT continues to participate in the Spanish worker's movement, focusing its efforts on the principles of workers' self-management, federalism, and mutual aid.

Organization and function

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

Membership

The CNT says of its membership, "We make no distinction at the time of admission, we require only that you are a worker or a student, employed or unemployed. The only people who cannot join are those belonging to repressive organizations (police, military, security guards), employers or other exploiters".[2]

Objectives

As a union organization, and in accordance with its bylaws, the aims of the CNT are to "develop a sense of solidarity among workers", hoping to improve their conditions under the current social system, prepare them for future emancipation, when the means of production have been socialized, to practice mutual aid amongst CNT collectives, and maintain relationships with other like-minded groups hoping for emancipation of the entire working class.[3] The CNT is also concerned with issues beyond the working class, desiring a radical transformation of society through revolutionary syndicalism.[4] To achieve their goal of social revolution, the organization has outlined a social-economic system through the confederal concept of anarchist communism, which consists of a series of general ideas proposed for the organization of an anarchist society.[5] The CNT draws inspiration from anarchist ideas, and also identifies with the struggles of different social movements. The CNT is internationalist, but also supports communities' right of self-determination and their sovereignty over the state.[6]

Structure

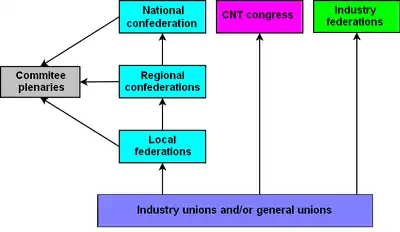

The organizational structure of the CNT is based on direct democracy.[7]

Industrial union and various posts union

The industrial unions (sometimes referred to as "branch unions") form the base structure of the CNT. Each industrial union groups together workers of different crafts within an industry. When there are fewer than 25 people working in one particular industry, a various posts union is formed for that industry, rather than multiple industry unions. A various posts union can include workers from different crafts and industries; it requires a minimum of five people.[8] If this number cannot be reached, four or fewer workers can form a confederal group. Due to the small size of the CNT, a majority of its unions are various posts unions.[9]

The decision-making power of the industry and various posts unions resides in the union assembly: decisions are taken by all of the workers of the union in question via a system of direct democracy and consensus. These assemblies may address any number of issues, whether "local, provincial, regional, national or international".[10]

Union sections

Union sections are assemblies of union workers who work in the same work centre or small business. The assembly of the union section chooses a delegation for the union section, which is usually rotated and which will represent the opinions of the union section in meetings with other entities, although it does not have decision-making powers.

Committees and secretaryships

The assembly chooses a committee to carry out routine or administrative duties that do not require the discussion of all members; the committee does not have decision-making powers. Committees can organise themselves through different departments, including propaganda, culture and archives; press and information; treasury and economic affairs; legal and prisoner advocacy; union action; social action; and general secretariat. The number of secretaryships can vary, sometimes two or more overlapping on a single one if considered necessary. Delegations from the union sections of the branch businesses are also part of the committee.

Federations and confederations

Unlike organizations that are organized from the top down, the CNT organises itself in an anarchistic fashion, from the bottom up, through different levels of confederations, following the Principle of Federation. The reason for favoring this structure is intended to limit homogeneity in committees, and keep them from having politics or programs. It is also intended to minimize the power of individuals who may be more active in the organization.[11]

Local and comarcal federations

The different industry and various posts unions of a particular municipality constitute the local federation[9] of unions that are coordinated by means of a local committee which has the same characteristics and powers as the union committees. The local committee is selected in the local plenary assembly to which every industry and various posts union can send delegations with written agreements previously adopted in their assembly. CNT has Local Federations in Madrid, Barcelona, Granada, and Seville.[12] In turn, the unions of neighbouring municipalities can group together into a comarcal federation.

Regional confederations

|

Andalusia

Aragon-La Rioja

Asturias-León

Canary Islands

Catalonia-Balearics

Central |

Extremadura

Galicia

Levante

Murcia

North |

A regional confederation brings together several local unions within a geographic regional zone. The structure is the same again: a regional committee with a secretary general and the rest of the Secretariats in a regional plenary to which the local unions send delegations with written agreements previously made in the assembly. The regional division of the CNT has undergone changes through time.

National confederation

The regional confederations send representative delegations—again on the same basis—to the national plenary assembly, which constitutes the national confederation. The national plenary of regional confederations elects a national general secretary, who moves the CNT headquarters to his/her place of residence. Hence, the CNT has no fixed headquarters.

The local plenary of the local federation chosen as headquarters gathers to designate the rest of the secretarial offices. The General Secretary and the rest of the secretaries form the Permanent Secretariat of the National Committee (SPCN, in Spanish) of the CNT, along with the General Secretariats of each of the regions. As in every committee in the CNT, their capacities are technical or administrative: they have no authority to make decisions for others.

Congress of the CNT

Direct representatives of the industry and various posts unions attend the CNT Congress with agreements from their own assemblies, independently from the local and regional levels. Among its duties, the Congress has to decide upon the CNT general line of action, and can appoint new National Committees. Since the foundation of the CNT in 1910 and the initial constitutional congress in September 1911,[13] nine congresses have taken place, four prior to the Spanish Civil War, and six since the Spanish transition to democracy.

The Congress is convened by the National Committee a year beforehand when there is an imperative need or there are new issues to assess. The discussion subjects are presented after being confirmed in a national plenary session, and then seven months before the Congress each member union starts its own debate which culminates with the presentation of their ideas to the Congress.

Plenarias and plenary assemblies

The meetings of the various committees (local, regional, national) are called plenarias. Plenarias cannot take decisions, only develop technical and administrative issues, as they are constituted by committees without decision-making powers.

Another method of decision-making is through local and regional plenaries (or plenary assemblies), and congresses, in which industry and various posts unions take active part sending delegations with previously reached and written agreements. The National Plenary does not follow this rule, as in this case the delegations with the written agreements come from the regional confederations.

Conferences

CNT conferences are open meetings in which matters are discussed and themes proposed; they serve to take the pulse of general opinion within the organization at any given moment. The discussions are later passed on to the local unions for their perusal. Persons representing themselves or another group or trade union may attend, but they cannot pass resolutions.

Industry federations

Industry federations are organized by branch of production, not geographically. All CNT unions in a particular branch of production form the national industry federation of that branch, differing from the structure of branch unions organized by local and regional federations and confederations. Industry federations exist on a regional level as well. Industry federations are empowered to act regarding matters lying within their area of responsibility. They send representatives that can speak, but not vote, at the national and regional confederations.

Relationship with the ICL

The International Confederation of Labour (ICL, CIT in Spanish), founded in 2018 in Parma, Italy, is a transnational organization which consists of delegations from a number of countries. The organizations are known as the sections of the ICL. CNT is the Spanish section.[9]

Media

The CNT journal CNT, or Periódico CNT (CNT Journal),[14] operates autonomously. Its directorship and headquarters are chosen in a congress or national plenary. The directorship manages its distribution, printing, sales, and subscriptions, as well as selecting from among articles submitted. The chosen director attends the CNT National Committee's meetings on a non-voting basis. The Secretary General of the CNT is responsible for writing Periódico CNT's editorial page. Periódico CNT is published monthly, under a Creative Commons copyleft license and it is available in printed and online format.

All organs and trade unions within the CNT may have their own media. Solidaridad Obrera ("Workers' Solidarity") is the journal of the Regional Confederation of Labor of Catalonia. It was established in 1907,[15] being the oldest communication medium of the CNT. Other media are La tira de papel, the Graphic Arts, Media and Shows National Coordinator bulletin; the Cenit, newspaper of the Regional Committee of the Exterior;[16] and BICEL, edited by the Anselmo Lorenzo Foundation,[17] which was created in 1987.[18] The foundation works autonomously, and its directorship is elected in a national plenary congress. Some of its duties are to maintain, catalogue and publicly display historic properties of the CNT, to publish books and other media, including BICEL, the Internal Bulletin of Centers of Anarchist Studies, to prepare cultural events during CNT or AIT congresses: lectures, debates, conferences, video forums, book presentations, etc., and to coordinate with other similar projects.

Voting

The CNT generally avoids bringing matters to a vote, preferring consensus decision-making, which it considers to be more in tune with its anarchist principles. While pure consensus is plausible for individual base unions, higher levels of organizations cannot completely avoid the need for some type of vote, which is always done openly by a show of hands.[19]

| Size of union[20] | Votes | |

|---|---|---|

| From | To | |

| 1 | 50 | 1 |

| 51 | 100 | 2 |

| 101 | 300 | 3 |

| 301 | 600 | 4 |

| 601 | 1,000 | 5 |

| 1,001 | 1,500 | 6 |

| 1,501 | 2,500 | 7 |

| 2,500 | more | 8 |

The problem arises when decisions have to be made in local or regional plenaries or congresses. It has already been explained that the basic structure of the CNT is the industrial union branch, or where these do not exist, the union of various occupations. Well then, there is no completely fair method for making decisions through voting:

- If each union gets one vote, a union of 1,000 members would have the same voice in decisions as a union of 50. Two unions of 25 (2 votes) could impose their will upon a union of 1,000 (1 vote).

- If votes are by the number of members, a union of 2,000 members would have 2,000 votes, and 100 unions of 20 members would have the same voice in decisions as just one union. The geographical distribution of 100 unions is wider than that of just one, but an agreement obligates all unions equally even though a small union would have the same responsibility to enforce it as a big union, in spite of the greater difficulty for the small one.

- We find besides the problem of minorities. For example, union A decides to go on strike by 400 votes against 350, and would have to support its decision to strike, since that was the outcome of its assembly. Union B of the same local federation says no to the strike by 100 votes to 25. Union C of the local federation says yes by a unanimous 15 votes. There are thus two unions in favour of the strike and one against, so a strike would be called if based on one vote per union. But adding the negative votes together, 450 voted against the strike, leaving 440 in favour.

— Basic Anarcho-syndicalism[21]

The CNT attempts to minimize this problem by a system of limited proportional voting. Even so, this system has some failures and may discriminate against unions with larger memberships. As an example, "ten unions with 25 adherents would total 250 members having 10 votes. This would be more votes than a union of 2,500, which with 10 times more members would only have the right to 7 votes."[19] Within the CNT this isn't considered a major problem, because agreements tend to reach consensus after long discussions. However, due to the nature of consensus decision-making, the final agreements consensed to may bear little resemblance to the initial proposals brought to the table.[19]

Methods

The CNT is rooted in three basic principles: workers' self-management or autogestión, federalism and mutual aid,[8] and considers that work conflicts must be settled between employers and employees without the action of such intermediaries as official state organisms or professional unionists. This is why the union criticizes union elections and works councils as means of control for managers, preferring workers' assemblies, union sections and direct action.[8] Also, when possible, the CNT avoids taking legal action through the courts. Administrative positions in the union rotate and are unpaid.[22] They prefer linear salary raises to increases that are percentage based, because the former increase equality of salaries. (That is, they prefer that all workers have their pay raised by the same absolute amount rather than the same percentage of their previous wage.)

The CNT's usual methods of action include exhibiting banners in front of the headquarters of companies with which the union has a conflict, and calls for consumer boycotts of their products and for social solidarity with the aggrieved workers. During strikes, resistance funds are created to help strikers and their families economically.

The CNT is organized around craft unions. This practice was adopted around 1918 in times of great class struggle under the reign of Alfonso XIII:

There were detentions aplenty in both crafts, so the pasta-makers craft, which included four hundred skilled workers, was disabled to act for lack of people. But then the whole food craft solidarizes: the furnacers, confectioners, millers, did the work of their arrested colleagues. And the carpenters, lathe operators, varnishers, the whole wood craft were set to relieve the saboteurs. The cabinet-makers' strike lasted seventeen weeks. Until the employers acceded… It was an overwhelming success. And the solidarity lesson was, rigorously, what impulsed the creation of The One Wood Union—the one that was famous—and the Food one, comprising all the sector unions.

— Joan Ferrer, in Baltasar Porcel's La revuelta permanente

History

The early years

The Spanish anarchist movement lacked a stable national organization during its early years. The anarchist Juan Gómez Casas described the evolution of the anarchist organization prior to the creation of the CNT:

After a period of drift, the Worker's Federation of the Spanish Region disappeared and was replaced by the Anarchist Organization of the Spanish Region… This organization then changed, in 1890, to the Aid and Solidarity Pact, which dissolved itself in 1896 due to repressive legislation against anarchism, splitting into several autonomous workers' societies and entities… Those who still remained from the WFSR founded Solidaridad Obrera in 1907, the direct ancestor of the CNT.

— Juan Gómez Casas

At the beginning of the 20th century there was a consensus among anarchists that a new national labor organization was necessary, to bring coherence and strength to the movement. During the Bourbon restoration (1874–1931), carried out by the traditional and dynastic parties represented by Cánovas del Castillo and Mateo Sagasta, a large portion of the workers' movement united around the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party as a political force, and around the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT, "Workers' General Union") for collective bargaining purposes. There were also republican movements with a stronger parliamentary emphasis, which was supported by a portion of the new bourgeoisie.

In 1910, in the middle of the restoration, the CNT was founded in Barcelona in a congress of the Catalan trade union Solidaridad Obrera (Workers' Solidarity) with the objective of constituting an opposing force to the then-majority trade union, the socialist UGT and "to speed up the economic emancipation of the working class through the revolutionary expropriation of the bourgeoisie". The CNT started small, counting 26,571 members represented through several trade unions and other confederations.[13]

In 1911, coinciding with its first congress, the CNT initiated a general strike that provoked a Barcelona judge to declare the union illegal[13] until 1914. That same year of 1911, the trade union officially received its name.

In 1916 the CNT changed its strategy respecting the UGT, establishing new relations that allowed the two unions to initiate the general strike of 1917 jointly. The second congress of the CNT in 1919 studied the possibility of merging both organizations to unify the Spanish labor movement. That same congress approved linking the CNT to the Third International, but after Ángel Pestaña's visit to the Soviet Union, and on his advice, they broke definitively from the Third International in 1922.

Peak of the CNT

From 1918 on the CNT grew stronger. Around that time, panic spread among employers, giving rise to the practice of pistolerismo (employing thugs to intimidate active unionists), causing a spiral of violence which significantly affected the trade union. These pistoleros were known to have killed 21 union leaders in 48 hours.[23]

The CNT had an outstanding role in the events of the La Canadiense general strike, which paralyzed 70% of industry in Catalonia in 1919, the year the CNT reached a membership of 700,000.[24] The Government settled the strike by granting all the striking workers demands that included an eight-hour day, union recognition, and the rehiring of fired workers.

In 1922 the International Workingmen's Association (later International Workers' Association) was founded in Berlin; the CNT joined immediately. However, the following year, with the rise of Miguel Primo de Rivera's dictatorship, the labor union was outlawed, once again.[25]

In 1927 with the "moderate" positioning of some cenetistas (CNT members) the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI), an association of anarchist affinity groups, was created in Valencia. The FAI would play an important role during the following years through the so-called trabazón (connection) with the CNT, that is, the presence of FAI elements in the CNT, encouraging the labor union not to move away from its anarchist principles, an influence that continues today.[26]

The Second Republic

After the fall of the monarchy in 1931, the CNT offered minimal support to the Second Republic. This support decreased progressively during the years between 1931 and 1933 because of constant confrontations with the republican authorities in the successive general strikes. The end of that period was marked by so-called revolutions of January and December, both of which were swiftly suppressed by the government. In those days the CNT functioned primarily in Catalonia, but was also gaining importance in other regions, such as Andalusia and Aragon (where it had a higher membership than the UGT).

In Ceuta, the CNT's organ was the weekly Despertar, launched in December 1931, but its publication was discontinued the next year.[27][28]

Tensions between the radical faístas, or FAI members, and the moderate non-faístas were constant and difficult to analyze because of the decentralized and sectorial nature of the organization. Finally, in 1931 a group of moderates published the Manifesto of the Thirty, which would give rise to Treintism (from treinta, thirty in Spanish), and in 1932 Ángel Pestaña split from the CNT to create the Syndicalist Party.[29]

In January 1932 a revolutionary strike organized by the CNT took place in Alt Llobregat, Catalonia.[30] In some places the workers took control of the streets and proclaimed libertarian communism replacing the republican flags with the red and black ones.[31] The strike was suppressed by the use of the police and the military[32] and several leading figures of the workers' side were arrested and some deported to Spanish colonies in Africa (Spanish Morocco, Western Sahara and Guinea).[33][30]

In January 1933 a revolution was carried out by the CNT.[34][35] The first acts of the insurrection took place in January 1st, with bombs exploding in La Fulguera, Asturias, and street riots in Seville, Lleida and Pedro Muñoz. By 8 January the revolution had spread to most of Spain reaching its greatest resonance in Andalusia.[36] The revolution was violently suppressed: in Bugarra, where the workers had proclaimed libertarian communism after an intense combat with the police, the Guardia Civil retook control of the town and killed 10 peasants while also detaining 250 more.[37] The most well-known case of repression was the Casas Viejas incident which discredited the government partly leading to its electoral defeat in 1933 elections.[38] During riots in Casas Viejas, where workers had proclaimed libertarian communism, two police officers were wounded, leading the government to send larger police forces to arrest rioters and stop the rebellion.[39] Many peasants fled the town but a group of anarchists resisted arrest and were barricaded in the house of an anarchist, Francisco Cruz Gutiérrez.[40] When the guards under the command of Captain Rojas arrived, they set the house on fire with the anarchists and their families still inside. Everyone inside the house was killed except for Maria Silva Cruz and a little boy.[40] The police then gathered all villagers who owned a gun, marched them to the ashes of the burned house and shot them dead.[40]

The third insurrection carried out by the CNT during the Second Spanish Republic was in December 1933 after the 1933 elections. It had its epicenter in Zaragoza and more generally in Aragon and La Rioja and it extended to parts of Extremadura, Andalusia, Catalonia and the mining basin of León. It lasted about a week before being completely dominated by law enforcement and in some places by the intervention of the army.[41]

The two years governed by the coalition of the center to center-right Partido Republicano Radical and the right to far-right CEDA were marked by mostly clandestine CNT activity, in the face of severe government repression. During the socialist Revolution of October 1934 (at which point membership in the CNT reached 1.58 million)[42] the CNT participated only from the background. However, the CNT's Regional Confederation of Labor of Asturias, León and Palencia actively participated in the revolution because of its loyalty to workers' alliances, this time formalized through the Uníos Hermanos Proletarios (UHP; Unite Brothers of the Proletariat)[43] in the pact with the UGT and the Asturian Socialist Federation. Thus, in La Felguera and in El Llano district of Gijón there were short periods when anarchist communism was put into practice:

In the El Llano barricade they proceeded to regularize life according CNT postulates: socialization of wealth and abolition of authority and capitalism. It was a brief experience of great interest, as the revolutionaries did not rule the town. […] A procedure was followed similar to the one in La Felguera. For organization of consumption a Supply Committee was created, with street delegates established in the grocery stores who controlled the number of neighbors in each street and produced the distribution of food. This street-by-street control made it easy to determine the amount of bread and other goods needed. The Supply Committee managed the general control over the available stock, especially flour.

— Manuel Villar, Anarchism in the Asturian Insurrection: The CNT and FAI in October 1934

It is believed that 30,000 people were imprisoned during this period. The successful transportation strike in Zaragoza, followed by a more-than-two-week general strike, was convoked in 1935 jointly with the UGT. However, this collaboration was not to be repeated in later actions.

After Lerroux's government crumbled, the 1936 elections placed the CNT at a crossroads. Opinions inside the organization were split among the supporters of abstentionism, those who wanted to allow the workers to choose whether or not to vote, or those directly advocating a vote for the Popular Front. This coalition party promised amnesty for prisoners, and part of the growth of the Front appears to have been thanks to the anarchist vote.

The CNT held a congress in Saragossa on 1 May, ratifying the position that the union should make no pacts with any political party, despite UGT leader Largo Caballero's attempts to persuade the union to stand in unity with the UGT.[44]

On 1 June, the CNT joined the UGT in declaring a strike of "building workers, mechanics, and lift operators." A demonstration was held, 70,000 workers strong. Members of the Falange attacked the strikers. The strikers responded by looting shops, and the police reacted by attempting to suppress the strike. By the beginning of July, the CNT was still fighting, while the UGT had agreed to arbitration. In retaliation to the attacks by the Falangists, anarchists killed three bodyguards of the Falangist leader José Antonio Primo de Rivera. The government then closed the CNT's centers in Madrid, and arrested David Antona and Cipriano Mera, two CNT militants.[45]

The Civil War

1936

After periods of clandestine operation followed by other shorter periods of legalization, in 1936 the CNT was finally legalized, and would remain legal until the end of the Civil War. During the war, the union collaborated with other republican groups opposed to the Nationalists. As the war developed, members of the CNT came to form part of the government of the Republic, holding various ministries and high positions within the administration. In Barcelona, the anarchists managed the majority of the functions of society, collectivizing a large part of the activity of the city.

Across the border from Catalonia in the nominally Republican eastern portion of the divided Aragon, the republican state was similarly powerless. The Confederal militias, which occupied Lower Teruel and Huesca, established defense committees that replaced the old city councils. In zones that had more anarchist presence before the war, collectivization of the land was carried out with great success. These first collectivizations were voluntary and were established from the lands that belonged to the members and those which had been requisitioned from those who were fugitive or missing. Those property-owners who wanted to keep possession of their land were not allowed to hire outside their families, and those lands they could not farm passed under community control.

Some of the most important communities in this respect were those of Alcañiz, Calanda, Alcorisa, Valderrobres, Fraga or Alcampel. Not only were the lands collectivized, but collective labours were also undertaken, like the retirement home in Fraga, the collectivization of some hospitals (such as in Barbastro or Binéfar), and the founding of schools such as the School of Anarchist Militants. These institutions would be destroyed by the Nationalist troops during the war.

The committee held an extraordinary regional plenary session to protect the new rural organization, gathering all the union representatives from the supporting villages and backed by Buenaventura Durruti. Against the will of the mainly Catalan CNT National Committee, the Regional Defence Council of Aragon was created.

The Civil War era also showed a spirit of sexual revolution. The anarchist women's organization Mujeres Libres established an equal opportunity for women in a society that traditionally had held women in lower regard. Women acquired power they had not previously had in Spanish society, fighting at the front and doing heavy jobs, things that had been forbidden to them until then. Free love became popular, although some parents' distrust produced the creation of the revolutionary weddings, informal ceremonies in which the couples declared their status, and that could be annulled if both parties didn't want to continue their relationship.[46]

Following Largo Caballero's assumption of the position of Prime Minister of the government, he invited the CNT to join in the coalition of groups making up the national government. The CNT proposed instead that a National Defense Council should be formed, led by Largo Caballero, and containing five members each from the CNT and UGT, and four "liberal republicans". When this proposal was declined, the CNT decided not to join the government. However, in Catalonia, the CNT joined the Central Committee of the Anti-Fascist Militias, which joined the Generalitat on 26 September. For the first time, three members of the CNT were also members of the government.[47]

In November, Caballero once again asked the CNT to become part of the government. The leadership of the CNT requested the finance and war ministries, as well as three others, but were given four posts, the ministries of health, justice, industry, and commerce. With Federica Montseny became Minister of Health, the first female minister in Spain. Juan García Oliver, as minister of justice, abolished legal fees and destroyed all criminal files. Shortly afterwards, despite the disapproval of the anarchist ministers, the capital was moved from Madrid to Valencia.[48] In Catalonia CNT was instrumental in preventing a Catalanist coup d'etat, planned in November by Estat Català.[49]

On 23 December 1936, after receiving in Madrid a retinue formed by Joaquín Ascaso, Miguel Chueca and three republican and independent leaders, the government of Largo Caballero, which by then had four anarchists as ministers (García Oliver, Juan López, Federica Montseny and Joan Peiró), approved the formation of the National Defense Committee. It was a revolutionary body which represented anarchists as much as socialists and republicans.

1937

Halfway through February 1937, a congress took place in Caspe with the purpose of creating the Regional Federation of Collectives of Aragon. 456 delegates, representing more than 141,000 collective members, attended the congress. The congress was also attended by delegates of the National Committee of the CNT.[50]

At a plenary session of the CNT in March 1937, the national committee asked for a motion of censure to suppress the Aragonese Regional Council. The Aragonese regional committee threatened to resign, which thwarted the censure effort. Though there had always been disagreements, that spring also saw a great escalation in confrontations between the CNT-FAI and the Communists. In Madrid, Melchor Rodríguez, who was then a member of the CNT, and director of prisons in Madrid, published accusations that the Communist José Cazorla, who was then overseeing public order, was maintaining secret prisons to hold anarchists, socialists, and other republicans, and either executing, or torturing them as "traitors". Soon after, on this pretext, Largo Caballero dissolved the Communist-controlled Junta de Defensa.[51] Cazorla reacted by closing the offices of Solidaridad Obrera.[52] In Catalonia, the Catalan Communists in the Catalan government made several demands that provoked the ire of the anarchists, in particular the call for turning all weapons over to the control of the government. The 8 April 1937 issue of Solidaridad Obrera opined, "We have made too many concessions and have reached the moment of turning off the tap,"[53] while the 2 May issue urged workers to prevent the government from disarming them. On the 25th, Juan Negrín sent security forces to take over posts on the French border in the Pyrenees that had until then been controlled by the CNT, anarchists in Bellver de Cerdanya fought with Negrín's carabineros, and Roldán Cortada, the Communist leader of the UGT was killed, allegedly by an anarchist. Cortada's funeral was used by the PSUC as an anti-CNT demonstration. Because of all the conflict, the UGT and CNT agreed with the Generalitat to cancel any celebrations on May Day. On 3 May, Assault Guards of the government attempted to take over the CNT-controlled telephone exchange building in Barcelona, but were held off by gunfire. The assault guard laid siege to the building, and fighting between the anarchists and POUM on one side, and Communists and the government forces on the other began. Leaders of the CNT attempted to acquire the resignation of the Communists they felt were responsible for the conflict, but to no avail.

The next day CNT's regional committee declared a general strike. The CNT controlled the majority of the city, including the heavy artillery on the hill of Montjuïc overlooking the city. CNT militias disarmed more than 200 members of the security forces at their barricades, allowing only CNT vehicles to pass through.[54] After unsuccessful appeals from the CNT leadership to end the fighting, the government began transferring Assault Guard from the front to Barcelona, and even destroyers from Valencia. On 5 May, the Friends of Durruti issued a pamphlet calling for "disarming of the paramilitary police… dissolution of the political parties…" and declared "Long live the social revolution! – Down with the counter-revolution!" The pamphlet was quickly denounced by the leadership of the CNT.[55] The next day, the government agreed to a proposal by the leadership of the CNT-FAI, that called for the removal of the Assault Guards, and no reprisals against libertarians that had participated in the conflict, in exchange for the dismantling of barricades, and end of the general strike. However, neither the PSUC or the Assault Guards gave up their positions, and according to historian Antony Beevor "carried out violent reprisals against libertarians"[56] By 8 May, the fighting was over.

These events, the fall of Largo Caballero's government, and the new prime ministership of Juan Negrín soon led to the collapse of much that the CNT had achieved immediately following the rising the previous July. At the beginning of July, the Aragonese organizations of the Popular Front publicly declared their support for the alternative council in Aragon, led by their president, Joaquín Ascaso. Four weeks later the 11th Division, under Enrique Líster, entered the region. On 11 August 1937, the Republican government, now situated in Valencia, dismissed the Regional Council for the Defense of Aragon.[57] Líster's division was prepared for an offensive on the Aragonese front, but they were also sent to subdue the collectives run by the CNT-UGT and in dismantling the collective structures created the previous twelve months. The offices of the CNT were destroyed, and all the equipment belonging to its collectives was redistributed to landowners.[57] The CNT leadership not only refused to allow the anarchist columns on the Aragon front to leave the front to defend the collectives, but they failed to condemn the government's actions against the collectives, causing much conflict between it and the rank and file membership of the union.[58]

1938–1939

In April 1938, Juan Negrín was asked to form a government, and included Segundo Blanco, a member of the CNT, as minister of education, and by this point, the only CNT member left in the cabinet. At this point, many in the CNT leadership were critical of participation in the government, seeing it as dominated by the Communists. Prominent CNT leaders went so far as to refer to Blanco as "sop of the libertarian movement"[59] and "just one more Negrínist."[60] On the other side, Blanco was responsible for installing other CNT members into the ministry of education, and stopping the spread of "Communist propaganda" by the ministry.[61]

In March 1939, with the war nearly over, CNT leaders participated in the National Defense Council's coup overthrowing the government of the Socialist Juan Negrín.[62] Those involved included the CNT's Eduardo Val and José Manuel González Marín serving on the council, while Cipriano Mera's 70th Division provided military support, and Melechor Rodríquez became mayor of Madrid.[63] The council attempted to negotiate a peace with General Francisco Franco, though he granted virtually none of their demands.

The CNT during the Francoist dictatorship

In 1939 the Law of Political Responsibilities outlawed the CNT[64] and expropriated its assets.[65] At that time the organization had a million members and a large infrastructure. According to one estimate, roughly 160,000–180,000 members of the CNT were killed by the Franco government.[66]

The CNT acted clandestinely inside Spain during the Franco years, as well as conducting activities from exile, and some members kept on fighting the Spanish State until 1948 through the guerrilla actions of maquis. There was much disagreement amongst factions of the CNT during these years. There was a major split after the National Committee inside Spain chose to support members of the Republican government in exile, while members of the Libertarian Movement in Exile (MLE) (basically the CNT-in-exile) stood against further collaboration with the government. Even Federica Montseny, who had joined the Republic as Minister of Health changed her stance on collaboration, describing the "futility of...participation in the government."[67]

In January 1960, the MLE was formed by the CNT, the FAI, and the FIJL. In September of the next year, a congress was held in Limoges, at which the Sección Defensa Interior (DI) was created, to be partially funded by the CNT. By this point, a great majority of the CNT-in-exile had given up on political action as a tool, and one of the main goals of the DI was to assassinate Franco.[68]

These divergent attitudes combined with Franco's repression to weaken the organization, and the CNT lost influence among the population inside Spain.[65] In 1961 it began to regain strength, consolidating itself during the 1960s and 1970s thanks to penetration of anarcho-syndicalist ideology into Catholic anti-Francoist workers' organizations such as the Hermandad Obrera de Acción Católica (HOAC, "Worker Brethren of Catholic Action") or Juventud Obrera Católica (JOC, "Catholic Worker Youth").

During the "transition"

.JPG.webp)

After Franco's death in November 1975 and the beginning of Spain's transition to democracy, the CNT was the only social movement to refuse to sign the 1977 Moncloa Pact,[69] an agreement amongst politicians, political parties, and trade unions to plan how to operate the economy during the transition. In 1979, the CNT held its first congress since 1936 as well as several mass meetings, the most remarkable one in Montjuïc. Views put forward in this congress would set the pattern for the CNT's line of action for the following decades: no participation in union elections, no acceptance of state subsidies,[7] no acknowledgment of works councils, and support of union sections.

In this first congress, held in Madrid,[70] a minority sector in favor of union elections split from the CNT, initially calling themselves CNT Valencia Congress (referring to the alternative congress held in this city), and later Confederación General del Trabajo (CGT) after an April 1989 court decision determined that they could not use the CNT initials.[71] In 1990, a group of CGT members left this union because they rejected the CGT's policy of accepting government subsidies, founding Solidaridad Obrera.

One year before, the 1978 Scala Case affected the CNT. An explosion killed three people in a Barcelona night club.[72] The authorities alleged that striking workers "blew themselves up", and arrested surviving strikers, implicating them in the crime.[73] CNT members declared that the prosecution sought to criminalize their organization:[74]

It was evident that the police weren't looking for anything nor anyone—they already had the culprits—it was just about intimidating the cenetistsa and scaring away from the organization thousands of affiliate workers that, although they identified with the syndical line of the anarcho-syndicalists, they weren't determined to go a long way in their support, let alone to defy such police repression. Things weren't a joke, the news of new arrests created an insecurity atmosphere among great part of the members. On the other hand, the certainty of the implication of the CNT in the attack kept consolidating in the public opinion, which caused serious deterioration in the organization's image, and thus the anarchists'. If we add news of aggressions and assaults by fascist groups, which considerably increased those days, we can more or less picture the situation. Being an anarchist those days turned very unpleasant. The media made it unpopular; the police and ultra-rightwing groups made it dangerous.

— Revista Polémica, The Scala case. A trial against anarcho-syndicalism.

After its legalization, the CNT began efforts to recover the expropriations of 1939. The basis for such recovery would be established by Law 4/1986, which required the return of the seized properties, and the unions' right to use or yield the real estate. Since then the CNT has been claiming the return of these properties from the State.

In 1996, the Economic and Social Council facilities in Madrid were squatted by 105 CNT militants.[75] This body is in charge of the repatriation of the accumulated union wealth. In 2004 an agreement was reached between the CNT and the District Attorney's Office, through which all charges were dropped against the hundred prosecuted for this occupation.

Current status

The number of members currently in the CNT is not known. The regions with the largest CNT membership are the Centre (Madrid and surrounding area), the North (Basque country), Andalucía, Catalonia and the Balearic Islands.[76]

The CNT opposes the model of union elections and workplace committees[77] and is critical of labor reforms and the UGT and the CCOO,[78] standing instead on a platform of reivindicación, that is, "return of what is due", or social revolution.[79]

Symbols and culture

.jpg.webp)

The CNT, owing to its interests in the radical transformation of society, has sought to make free knowledge and culture accessible to workers, a task which has been developed through the support of the anarchist academies. The School of Anarchist Militants was an institution which, by means of anarchist pedagogy, sought to ensure that "groups of teenagers could acquire the knowledge and the personal responsibility essential to work in collectives such as those of entertainers and accountants." Through the Anselmo Lorenzo Foundation, the CNT manages its cultural heritage, edits books, and organizes conferences and colloquies. Also, some sections of the CNT have supported and promoted Esperanto.

The flag of the CNT is the traditional flag of anarcho-syndicalism, which joins diagonally the red color of the labour movement and the black color of anarchism, as a negation of nationalism and reaffirmation of internationalism.

The anthem of the CNT is A las barricadas (To the Barricades),[80] written by the Polish poet Wacław Święcicki with music by Józef Pławiński in 1883. Święcicki and Pławiński's work, called Warszawianka, was given Spanish lyrics by Valeriano Orobón Fernández and published with some musical arrangements for mixed choir by Ángel Miret in 1933.

Several postage stamps were issued by the CNT during the Spanish Civil War.[81] Other surviving artifacts of this period are posters,[82] movie tickets, and other objects related to the companies which were collectivized during the Spanish Revolution of 1936.

Robert Capa photographed the death of the Valencian Columna Alcoiana militiaman Federico Borrell García during the Spanish Civil War in the snapshot called "Death of a Loyalist Soldier".[83] This photograph has become a famous image which shows the calamity of war.[84]

In 1936, the film industry was collectivized[85] and produced short films such as En la brecha (In the Gap, 1937). The CNT has been portrayed in recent Spanish filmmaking by the Vicente Aranda's film Libertarias (1996), which shows a group of militiamen (and especially militiawomen) at the Aragon front during the Spanish Civil War.

References

- Woodcock 2004, p. 312

- "No hacemos distinción a la hora de la afiliación, los requisitos son: que seas trabajador o estudiante, en paro o en activo. Las únicas personas que no pueden afiliarse son aquellas que pertenecen algún cuerpo represivo (policías, militares, guardias de seguridad) ni empresarios u otros explotadores." CNT website. Archived 11 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish) Estatutos de la CNT de 1977 Archived 7 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine ("1977 Statutes of the CNT"), accessed online on Wikisource 31 January 2007.

- Roca Martínez 2006, p. 106

- CNT & Stein 1998

- CNT & Stein 1998

Anarcho-syndicalism is internationalist; it sees the world as a whole in spite of racial, language or cultural differences. In this sense, it opposes the oppression that the states exert over the people. We are against the Spanish state oppressing the Basque people, in favor of the Basque, Catalan, Palestine, Saharan, Tibetan, or Kurdish people being responsible for their own destinies, settling on more or less delimited territories, participating in the richness of the society as a whole, federating as they like, becoming independent from the states; but we would oppose just as strongly the creation of a Basque, Palestinian, Saharan or Kurdish state, with its police, army, currency, government and repressive instrument.

- Roca Martínez 2006, p. 109

- Roca Martínez 2006, p. 109

- Roca Martínez 2006, p. 110

- Roca Martínez 2006, pp. 109–110

- CNT & Stein 1998, p. 14

- Roca Martínez 2006, p. 115

- Geary 1989, p. 261

- "Periódico CNT". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- Gómez Casas 1986, p. 49

- Confederación Nacional del Trabajo, International Workingmen's Association (1983). Cenit : órgano de la CNT-AIT Regional del Exterior : portavoz de la CNT de España, CeNiT

- "REVISTA BICEL". Fundación de Estudios Libertarios Anselmo Lorenzo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- "Origen de la Fundación de Estudios Libertarios Anselmo Lorenzo" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 25 February 2008. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- CNT & Stein 1998, p. 21

- Roca Martínez 2006, p. 111

- CNT & Stein 1998, p. 20

- (in Spanish) CNT: otra forma de hacer sindicalismo Archived 8 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine ("CNT: another form of doing unionism"), official CNT site. Accessed online 6 January 2007.

- Beevor 2006, p. 15

- Beevor 2006, p. 13

- Beevor 2006, p. 17

- Roca Martínez 2006, p. 116

- Checa Godoy, Antonio. Prensa y partidos politicos durante la II republica. Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca, 1989. p. 87

- تحولات الأرياف في جبال الريف بالمغرب. Groupe de recherches géographiques sur le Rif, G.R.G. Rif. 2005. p. 171. ISBN 978-9954-8232-1-7.

- Horn 1996, p. 56

- Diccionari d'Història de Catalunya, p. 35, ed. 62, Barcelona, 1998, ISBN 84-297-3521-6

- Casanova, Julián (2007). República y Guerra Civil. Vol. 8 de la Historia de España, dirigida por Josep Fontana y Ramón Villares (in Spanish). Barcelona: Crítica/Marcial Pons. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-84-8432-878-0.

- Casanova, Julián (2007). República y Guerra Civil. Vol. 8 de la Historia de España, dirigida por Josep Fontana y Ramón Villares (in Spanish). Barcelona: Crítica/Marcial Pons. p. 67. ISBN 978-84-8432-878-0.

- Casanova, Julián (2007). República y Guerra Civil. Vol. 8 de la Historia de España, dirigida por Josep Fontana y Ramón Villares (in Spanish). Barcelona: Crítica/Marcial Pons. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-84-8432-878-0.

- Casanova, Julián (1997). De la calle al frente. El anarcosindicalismo en España (1931–1936) (in Spanish). Barcelona: Crítica. pp. 108–114. ISBN 84-7423-836-6.

- Gil Pecharromán, Julio (1997). La Segunda República. Esperanzas y frustraciones. Madrid: History 16. pp. 67–68. ISBN 84-7679-319-7.

- Casanova, Julián (1997). Ibid. p. 109.

- Ballbé, Manuel (1983). Orden público y militarismo en la España constitucional (1812–1983) (in Spanish). Madrid: Alianza Editorial. p. 357. ISBN 84-206-2378-4.

- Seidman, Michael (2011). The Victorious Counterrevolution. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780299249632.

- "Biografia de Maria Silva Cruz 'La Libertaria'". Portal Libertario Oaca (in Spanish). 12 March 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- Preston, Paul (May 1983). "The Anarchists of Casas Viejas/Spain 1808–1975/The Spanish Civil War (Book Review)". History Today. 33 (5): 55–56. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- Casanova, Julián (2007). República y Guerra Civil. Vol. 8 de la Historia de España, dirigida por Josep Fontana y Ramón Villares (in Spanish). Barcelona: Crítica/Marcial Pons. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-84-8432-878-0.

- Beevor 2006, p. 24

- Behind the Spanish barricades: reports from the Spanish Civil War, John Langdon-Davies, 1937

- Beevor 2006, p. 46

- Beevor 2006, p. 48

- Ackelsberg 2005, p. 167

- Beevor 2006, pp. 146–147

- Beevor 2006, p. 170

- Enric Ucelay-Da Cal, Arnau González i Vilalta (ed.), Contra Companys, 1936. La frustración nacionalista ante la revolución, Valencia 2012, ISBN 9788437089157

- Alexander 1999, p. 361

- Beevor 2006, p. 260

- Beevor 2006, p. 263

- Beevor 2006, p. 261

- Beevor 2006, pp. 263–264

- Beevor 2006, pp. 266–267

- Beevor 2006, p. 267

- Beevor 2006, p. 295

- Beevor 2006, p. 296

- Alexander 1999, p. 976

- Alexander 1999, p. 977

- Alexander 1999, p. 978

- Alexander 1999, p. 1055

- Beevor 2006, p. 490

- Bowen 2006, p. 248

- Aguilar Fernández 2002, p. 155

- Alexander 1999, p. 1095

- Guérin 2005, p. 674

- Christie 2002, p. 214

- Roca Martínez 2006, p. 108

- Aguilar Fernández 2002, p. 110

- "FAQ". Archived from the original on 9 February 2008.

Un sector minoritario que es partidario de las elecciones sindicales se escinde y pasa a llamarse CNT congreso de valencia (en referencia al Congreso alternativo realizado en esa ciudad) y posteriormente, perdidas judicialmente las siglas, a CGT.

- Alexander 1999, p. 1094

- Meltzer 1996, p. 265

- (in Spanish) A series of three articles about the Scala Case from the CNT point of view: (1) El Caso Scala. Un proceso contra el anarcosindicalismo Archived 29 June 2012 at archive.today, ("The Scala Case. A trial against anarcho-syndicalism"), Jesús Martínez, Revista Polémica online, 1 February 2006; (2) Segunda parte. El proceso Archived 9 September 2012 at archive.today ("Second part: the trial") 31 January 2006; (3) Tercera parte. El canto del Grillo Archived 13 September 2012 at archive.today ("Third part: Grillo's song") 31 January 2006. All accessed online 6 January 2008.

- "Los 117 detenidos de la CNT, en libertad tras prestar declaración". El Mundo (in Spanish). 7 December 1996. Retrieved 14 January 2008.

- Roca Martínez 2006.

- (in Spanish) ¿Que son las elecciones sindicales? Archived 9 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine, official CNT site. Accessed online 6 January 2008.

- (in Spanish) Otra reforma laboral ¿Y ahora qué? Archived 26 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine, official CNT site. Accessed online 6 January 2008.

- (in Spanish) Plataforma Reivindicativa Archived 29 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine, official CNT site. Accessed online 6 January 2008.

- Romero Salvadó, Francisco J. (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Spanish Civil War. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-8108-5784-1.

- (in French) Les trimbres édités par la CNT et la FAI entre 1936 et 1939 Archived 12 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine ("The stamps issued by the CNT and FAI between 1936 and 1939"), Increvables Anarchistes Archived 10 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Includes images of many stamps. Accessed 6 January 2008.

- "Spain 1936/1939, what are the anarchist posters during the civil war?". Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- The picture, taken 5 September 1936, is known by various similar names: "Death of a militiaman", "Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death, Cerro Muriano, 5 September 1936." See Federico Borrell García for image.

- Proving that Robert Capa's Falling Soldier is Genuine: a Detective Story, Richard Whelan, American Masters, PBS Website. Accessed 5 January 2008.

- (in Spanish) Cine y Anarquismo. 1936: colectivización de la industria cinematográfica. Archived 1 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine ("Film and anarchism. 1936: Collectivisation of the film industry"), official CNT site. Accessed 5 January 2008.

Film

- Living Utopia Anarchism/Anarcho-Syndicalism in Spain from around 1880–1940 Documentary by Juan Gamero, (1997).

Sources

- CNT (2001). Anarcosindicalismo básico (in Spanish). Seville: Federación Local de Sindicatos de Sevilla de la CNT-AIT. ISBN 84-920698-4-8.

- CNT; Stein, Jeff (1998). Basic Anarcho-Syndicalism (PDF). Johannesburg, South Africa: Zabalaza Books. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 7 January 2008. Excerpts from the 1998 edition of Anarcosindicalismo básico were translated by Jeff Stein and published first in the Anarcho-Syndicalist Review, then as a pamphlet (PDF linked). Direct quotations in this article follow Stein's wording for passages he has translated. Note that the pagination of the linked PDF places two pages of the pamphlet on each PDF page; cited page numbers follow the pamphlet itself.

- Aguilar Fernández, Palomar (2002). Memory and Amnesia: The Role of the Spanish Civil War in the Transition to Democracy. Berghahn Books. ISBN 1-57181-496-5.

- Ackelsberg, Martha A. (2005). Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women. Oakland: AK Press. ISBN 1-902593-96-0.

- Alexander, Robert (1999). Anarchists in the Spanish Civil War. Janus Publishing Company. ISBN 1-85756-412-X.

- Beevor, Antony (2006). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84832-5.

- Bowen, Wayne H. (2006). Spain During World War II. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1658-7.

- Christie, Stuart (2002). My Granny Made Me an Anarchist: The Cultural and Political Formation of a west of Scotland 'baby-boomer'. Christie Books. ISBN 1-873976-14-3.

- Christie, Stuart (2003). General Franco Made Me A 'Terrorist'. Christie Books. ISBN 1-873976-19-4.

- Fernández, Frank, Cuban Anarchism: The History of a Movement, See Sharp Press.

- Gómez Casas, Juan (1986). Anarchist Organisation: The History of the F.A.I.. Black Rose Books Limited. ISBN 0-920057-38-1.

- Geary, Dick (1989). Labour and Socialist Movements in Europe Before 1914. Berg Publishers. ISBN 0-85496-705-2.

- Guérin, Daniel (2005). No Gods No Masters: An Anthology of Anarchism. Translated by Sharkey, Paul. AK Press. ISBN 978-1-904859-25-3.

- Horn, Gerd-Rainer (1996). European Socialists Respond to Fascism: Ideology, Activism and Contingency in the 1930s. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-509374-7.

- Meltzer, Albert (1996). I Couldn't Paint Golden Angels: Sixty Years of Commonplace Life and Anarchist Agitation. Oakland: AK Press. ISBN 1-873176-93-7.

- Orwell, George (1938). Homage to Catalonia. ISBN 0-905712-45-5.

- Porcel, Baltasar (1978). La revuelta permanente (in Spanish). Barcelona: Editorial Planeta. ISBN 84-320-5643-X.

- Roca Martínez, Beltrán (2006). "Anarchism, anthropology and Andalucia: an analysis of the CNT and 'New Capitalism'" (PDF). Anarchist Studies. London: Lawrence & Wishart. 14 (2): 106–130. ISSN 0967-3393. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- Villar, Manuel (1994). El anarquismo en la insurrección de Asturias: la CNT y la FAI en octubre de 1934 (in Spanish). Madrid: Fundación Anselmo Lorenzo. ISBN 84-86864-15-1.

- Woodcock, George (2004). Anarchism: A History Of Libertarian Ideas And Movements. Broadview Press. ISBN 1-55111-629-4.

External links

- CNT-CIT Website (in Spanish)

- CNT-AIT Official website

(in Spanish)

(in Spanish)

- (in Spanish) Fundación de Estudios Libertarios Anselmo Lorenzo (FAL)

- (in Spanish) Directorio de Sindicatos, Federaciones y Confederaciones de la CNT (Directory of unions, federations, and confederations of the CNT)

- (in Spanish) Periódico CNT (CNT Journal)

- Articles on the CNT from the Kate Sharpley Library

- News and historical articles from libcom.org

- (in French) Images of CNT-related posters

- CNT del Interior Archives at the International Institute of Social History

- Footage of interviews with CNT-people, for the film De toekomst van '36 (The future of '36), at the International Institute of Social History