National Minimum Wage Act 1998

The National Minimum Wage Act 1998 creates a minimum wage across the United Kingdom.[2] From 1 April 2023, the minimum wage is £10.42 for people aged 23 and over, £10.18 for 21- to 22-year-olds, £7.49 for 18- to 20-year-olds, and £5.28 for people under 18 and apprentices.[3] (See Current and past rates.)

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An Act to make provision for and in connection with a national minimum wage; to provide for the amendment of certain enactments relating to the remuneration of persons employed in agriculture; and for connected purposes. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 1998 c. 39 |

| Introduced by | Margaret Beckett, President of the Board of Trade[1] |

| Territorial extent | England and Wales; Scotland; Northern Ireland |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 31 July 1998 |

Status: Current legislation | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

| Revised text of statute as amended | |

It was a flagship policy of the Labour Party in the UK during their successful 1997 general election campaign.[2] The national minimum wage (NMW) took effect on 1 April 1999. On 1 April 2016, an amendment to the act attempted an obligatory "National Living Wage" for workers over 25 (now extended to workers aged 23 and over), which was implemented at a significantly higher minimum wage rate of £7.20. This was expected to rise to at least £9 per hour by 2020,[4] but in reality by that year it had only reached £8.72 per hour.[5]

Background

No national minimum wage existed prior to 1998, although there were a variety of systems of wage controls focused on specific industries under the Trade Boards Act 1909. The Wages Councils Act 1945 and subsequent acts applied sectoral minimum wages. These were gradually dismantled until the Trade Union Reform and Employment Rights Act 1993 abolished the 26 final wages councils, which had protected around 2,500,000 low-paid workers.

Much of the Labour Party had long opposed a government minimum wage because they feared that would reduce the need for joining trade unions, which they supported. Also, they feared that the minimum wage would in practice become the maximum wage since employers would be satisfied with paying only that amount.

Part of the reason for the shift in Labour's minimum wage policy was the decline of trade union membership over recent decades (weakening employees' bargaining power),[2] as well as a recognition that the employees most vulnerable to low pay, especially in service industries, were rarely unionised in the first place. Labour had returned to government in 1997 after 18 years in opposition, and a minimum wage had been a party policy since as far back as 1986, under the leadership of Neil Kinnock.[6]

The implementation of a minimum wage was opposed by the Conservative Party[2] and supported by the Liberal Democrats.[7]

Overview

The NMW rates are reviewed each year by the Low Pay Commission, which makes recommendations for change to the Government.[8]

The following rates apply as of April 2023:[9]

- £10.42 per hour for workers aged 23 and over

- £10.18 per hour for workers aged 21-22

- £7.49 per hour for workers aged 18–20

- £5.28 per hour for under-18s

- £5.28 per hour for apprentices in their first year or under 19 years old

In his 2015 budget, George Osborne announced that from 1 April 2016, a further rate known as the "National Living Wage" ("NLW") will apply to those aged 25 or over and will be at the rate of £7.20 per hour. This was successfully introduced into legislation.[10] As of April 2022 this rate is £9.50 per hour and the minimum age threshold was decreased to 23 in April 2021.

Law

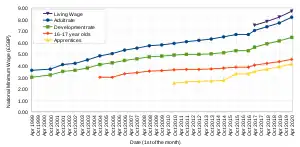

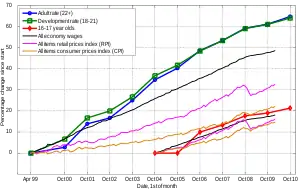

- 'Adult rate' is for employees aged 21 and over from 2010, and 22 and over prior to then.

- 'Development rate' is for employees aged 18–20 from 2010, and 18–21 prior to then.

- '16–17 year olds rate' was introduced in 2004; prior to that there was no minimum wage at this age.

- 'Apprentice rate' was introduced in 2010.

- 'National Living Wage' was introduced in April 2016, and applies to employees aged 25 and over.

The National Minimum Wage Act 1998 applies to workers (section 1(2)), that is, employees, and anyone who has a contract to do work personally, other than for a customer or a client (section 54(3)). Those working through agencies are included (section 34), so that the agencies' charges must not reduce a worker's basic entitlement. Home-workers are also included, and the Secretary of State can make order for other inclusions. The Secretary of State can also make exclusions, as has been done for au pairs and family members in a family business. Share fishermen paid by a share of profits are excluded, as are unpaid volunteers and prisoners (sections 43–45).

The hours that are used in a national minimum wage calculation are dependent upon work type as defined within the National Minimum Wage Regulations 1999.[11] The different work types are time work, salaried hours work, output work and unmeasured work. Hours to be paid for are those worked in the "pay reference period", but where pay is not contractually referable to hours, such as pay by output, then the time actually worked must be ascertained. The principle is that the rate of pay for hours worked should not fall below the minimum. Periods when the worker is on industrial action, travelling to and from work and absent are excluded. A worker who is required to be awake and available for work must receive the minimum rate. This does not prevent the use of "zero hour contracts", where the worker is guaranteed no hours and is under no obligation to work.

Workers' rights

Section 10 permits a worker to issue a "production notice" to their employer requesting access to the employer's records if they believe that their pay may be, or have been, below the national minimum wage.[12]

Enforcement

The NMW is enforceable by HMRC (section 14), or by the worker making a contractual claim or through a "wrongful deduction" claim under Part II of the Employment Rights Act 1996. Section 18 provides for compensation. Employers must not subject their workers to dismissal or any other detriment (section 25 and section 23).

In October 2013, new rules to publicise the names of employers paying under the minimum wage were established; the names of most employers issued with a Notice of Underpayment are published.[13] In 2014, the names of 30 employers were released by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills.[14][15] In 2017, the names of 852 employers were released by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.[16][17][18]

Failure to pay underpayments after issue of a notice of underpayment results in payment of a financial penalty to the Secretary of State.[19] In 2016, arrangements were made to ensure that underpayments result in double-level financial penalty.[20] The Low Pay Commission has highlighted that apprentices are particularly exposed to being underpaid.[21]

Case law

- Revenue and Customs Commissioners v Annabel’s (Berkeley Square) Ltd [2009] EWCA Civ 361, [2009] ICR 1123

- Spackman v LMU [2007] IRLR 741, entitlement to payment of wages

Statistics

The Office for National Statistics produces information about the lower end of the earnings distribution and estimates for the number of jobs paid below the national minimum wage.[22] The figures are based on data from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings.

Perspectives

The policy was opposed by the Conservative Party at the time of implementation, who argued that it would create extra costs for businesses and would cause unemployment. In 1996, The Conservative Party's future leader, David Cameron, standing as a prospective Member of Parliament for Stafford, had said that the minimum wage "would send unemployment straight back up".[23] However, in 2005 Cameron stated that: "I think the minimum wage has been a success, yes. It turned out much better than many people expected, including the CBI."[24] It is now Conservative Party policy to support the minimum wage.[25]

While Mayor of London, Boris Johnson, future Conservative Prime Minister, supported the London living wage, ensuring that all City Hall employees and subcontracted workers earn at least £7.60 an hour and promoting the wage to employers across the city. In May 2009, his Greater London Authority Economics unit raised the London Living Wage for City Hall employees to its current rate of £7.60, £1.80 more than the legal minimum rate of £5.80.[26]

To put the pay in an annual perspective, an adult over the age of 25 working at the minimum wage for 7.5 hours a day, 5 days a week, will make £1,417/month and £17,004/year Gross Income. After pay-as-you-earn tax (PAYE) this becomes £1266.89/month or £15,202.72/year (2019/2020).}[27][28] Full-time workers are also entitled to a minimum of 5.6 weeks paid holiday per year from 1 April 2009, with pro-rata equivalent for part-time workers. This includes public holidays.[29]

Current and past rates

| From | Age 23+ | Age 21-22 | Age 18-20 | Age 16-17 | Apprentice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 April 2023[31] | £10.42 | £10.18 | £7.49 | £5.28 | £5.28 |

| 1 April 2022[32] | £9.50 | £9.18 | £6.83 | £4.81 | £4.81 |

| 1 April 2021[33] | £8.91 | £8.36 | £6.56 | £4.62 | £4.30 |

| From | Age 25+ | Age 21–24 | Age 18–20 | Age 16–17 | Apprentice |

| 1 April 2020[34] | £8.72 | £8.20 | £6.45 | £4.55 | £4.15 |

| 1 April 2019[35] | £8.21 | £7.70 | £6.15 | £4.35 | £3.90 |

| 1 April 2018[3] | £7.83 | £7.38 | £5.90 | £4.20 | £3.70 |

| 1 April 2017[36] | £7.50 | £7.05 | £5.60 | £4.05 | £3.50 |

| 1 October 2016 | £7.20 | £6.95 | £5.55 | £4.00 | £3.40 |

| 1 April 2016[37] | £7.20 | £6.70 | £5.30 | £3.87 | £3.30 |

| From | Age 21+ | Age 18-20 | Age 16-17 | Apprentice | |

| 1 October 2015 | £6.70 | £5.30 | £3.87 | £3.30 | |

| 1 October 2014 | £6.50 | £5.13 | £3.79 | £2.73 | |

| 1 October 2013 | £6.31 | £5.03 | £3.72 | £2.68 | |

| 1 October 2012 | £6.19 | £4.98 | £3.68 | £2.65 | |

| 1 October 2011 | £6.08 | £4.98 | £3.68 | £2.60 | |

| 1 October 2010 | £5.93 | £4.92 | £3.64 | £2.50 | |

| From | Age 22+ | Age 18-21 | Age 16-17 | ||

| 1 October 2009 | £5.80 | £4.83 | £3.57 | – | |

| 1 October 2008 | £5.73 | £4.70 | £3.53 | – | |

| 1 October 2007 | £5.52 | £4.60 | £3.53 | – | |

| 1 October 2006 | £5.35 | £4.45 | £3.40 | – | |

| 1 October 2005 | £5.05 | £4.25 | £3.00 | – | |

| 1 October 2004 | £4.85 | £4.10 | £3.00 | – | |

| 1 October 2003 | £4.50 | £3.80 | £3.00 | – | |

| 1 October 2002 | £4.20 | £3.50 | – | – | |

| 1 October 2001 | £4.10 | £3.50 | – | – | |

| 1 October 2000 | £3.70 | £3.20 | – | – | |

| 1 April 1999 | £3.60 | £3.00 | – | – | |

See also

- History of the minimum wage

- Minimum wage

- List of minimum wages by country

- UK labour law

- Ex parte H.V. McKay (1907) 2 CAR 1, Australian labour law case on the living wage

- S Webb and B Webb, Industrial Democracy (1898)

- Liberal welfare reforms

- Trade Boards Act 1909

- Trade Boards Act 1918

- Wages Councils Act 1945

- Tax Credits and Child tax credit, Working tax credit

- Wage regulation

- Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which introduced the minimum wage in the US

- Incomes policy

Notes

- Hansard, National Minimum Wage Bill, 16 December 1997, accessed 5 February 2021

- "National Minimum Wage". politics.co.uk.. E McGaughey, A Casebook on Labour Law (Hart 2019) ch 6(1)

- "National Minimum Wage and National Living Wage rates". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Larry Elliott (30 March 2016). "Third of British workers may benefit from new legal pay level". The Guardian.

- Richard Partington (31 December 2019). "Government misses minimum wage target set by Tories in 2015". The Guardian.

- Margaret Thatcher (10 October 1986). "Speech to Conservative Party Conference". Margaret Thatcher Foundation. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- "National Minimum Wage Bill — 16 December 1997". The Public Whip. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- "Low Pay Commission - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk.

- "National Minimum Wage". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- Lisa Patmore; Tom Heys (22 July 2015). "Seven things you need to know about George Osborne's 'National Living Wage'". Lewis Silkin. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- National Minimum Wage Regulations 1999 www.opsi.gov.uk

- National Minimum Wage Act 1998, section 10

- "Government names employers who fail to pay minimum wage". gov.uk. 8 June 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- "Government gets tough with employers failing to pay minimum wage". gov.uk. 28 February 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "Government 'names and shames' minimum wage underpayers". BBC. 8 June 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- "Record number of employers named and shamed for underpaying". gov.uk. 15 February 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "Record £2 million back pay identified for 13,000 of the UK's lowest paid workers". gov.uk. 16 August 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "£1.7m back pay identified for a record 16,000 workers as 260 employers are named and shamed for underpaying minimum wage rates". gov.uk. 8 December 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- UK Legislation, National Minimum Wage Act 1998, section 19, accessed 22 June 2022

- The National Minimum Wage (Amendment) Regulations (2016), Explanatory Memorandum, SI 2016/68, made 22 January 2016, accessed 20 June 2022

- Low Pay Commission, Low Pay Commission urges action on illegal underpayment of apprentices, published 7 May 2020, accessed 13 September 2020

- "Low Pay Estimates". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- The Chronicle (Stafford), 21 February 1996

- Rawnsley, Andrew (18 December 2005). "I'm not a deeply ideological person. I'm a practical one". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- "Party plans would 'boost minimum pay for millions'". BBC News. 15 November 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- Greg Dickson (19 December 2011). "A Fairer London: The 2009 Living Wage in London". Hamilton Bradbury. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- "HM Revenue & Customs: Income Tax allowances". Hmrc.gov.uk. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "HM Revenue & Customs: National Insurance Contributions". Hmrc.gov.uk. 28 June 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Holiday entitlements: introduction : Directgov - Employment". Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- Low Pay Commission. Home page. Retrieved on 1 October 2014.

- "National MW and LW rates 2023".

- "National MW and LW rates 2022".

- "National Minimum Wage and National Living Wage rates".

- "National Minimum Wage and National Living Wage rates".

- "National Minimum Wage and National Living Wage rates".

- "National Minimum Wage and National Living Wage rates - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- "Osborne unveils National Living Wage". BBC News. 8 July 2015.

References

- E McGaughey, A Casebook on Labour Law (Hart 2019) ch 6(1)

- B Simpson, ‘A Milestone in the Legal Regulation of Pay’ (1999) 28 ILJ 1, 17-18

- B Simpson, ‘The National Minimum Wage Five Years On’ (2004) 33 ILJ 22