Industrial Revolution in Scotland

In Scotland, the Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes and economic expansion between the mid-eighteenth century and the late nineteenth century. By the start of the eighteenth century, a political union between Scotland and England became politically and economically attractive, promising to open up the much larger markets of England, as well as those of the growing British Empire, resulting in the Treaty of Union of 1707. There was a conscious attempt among the gentry and nobility to improve agriculture in Scotland. New crops were introduced and enclosures began to displace the run rig system and free pasture. The economic benefits of union were very slow to appear, some progress was visible, such as the sales of linen and cattle to England, the cash flows from military service, and the tobacco trade that was dominated by Glasgow after 1740. Merchants who profited from the American trade began investing in leather, textiles, iron, coal, sugar, rope, sailcloth, glass-works, breweries, and soap-works, setting the foundations for the city's emergence as a leading industrial center after 1815.

.jpg.webp)

The linen industry was Scotland's premier industry in the eighteenth century and formed the basis for the later cotton, jute, and woolen industries. Encouraged and subsidized by the Board of Trustees so it could compete with German products, merchant entrepreneurs became dominant in all stages of linen manufacturing and built up the market share of Scottish linens, especially in the American colonial market. Historians often emphasize that the flexibility and dynamism of the Scottish banking system contributed significantly to the rapid development of the economy in the nineteenth century. At first the leading industry, based in the west, was the spinning and weaving of cotton. After the cutting off of supplies of raw cotton from 1861 as a result of the American Civil War Scottish entrepreneurs and engineers, and its large stock of easily mined coal, the country diversified into engineering, shipbuilding, and locomotive construction, with steel replacing iron after 1870. As a result, Scotland became a center for engineering, shipbuilding and the production of locomotives.

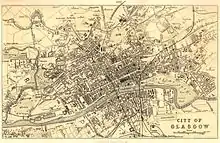

Scotland was already one of the most urbanized societies in Europe by 1800. Glasgow became one of the largest cities in the world, and known as "the Second City of the Empire" after London. Dundee upgraded its harbor and established itself as an industrial and trading center. The industrial developments, while they brought work and wealth, were so rapid that housing, town-planning, and provision for public health did not keep pace with them, and for a time living conditions in some of the towns and cities were notoriously bad, with overcrowding, high infant mortality, and growing rates of tuberculosis. Owners to support government sponsored housing programs as well as self-help projects among the respectable working class. Even with the growth of industry there were insufficient good jobs, as a result, during the period 1841–1931, about two million Scots emigrated to North America and Australia, and another 750,000 Scots relocated to England. By the twenty-first century, there were about as many people who were Scottish Canadians and Scottish Americans as the five million remaining in Scotland.

Background

By the start of the eighteenth century, a political union between Scotland and England became politically and economically attractive, promising to open up the much larger markets of England, as well as those of the growing British Empire. The Scottish parliament voted on 6 January 1707, by 110 to 69 to adopt the Treaty of Union. It was a full economic union. Most of its 25 articles dealt with economic arrangements for the new state known as "Great Britain". It added 45 Scots to the 513 members of the House of Commons of Great Britain and 16 Scots to the 190 members of the House of Lords, and ended the Scottish parliament. It also replaced the Scottish systems of currency, taxation and laws regulating trade with laws made in London. England had about five times the population of Scotland at the time, and about 36 times as much wealth.[1]

Major factors that facilitated industrialisation in Scotland included cheap and abundant labour; natural resources that included coal, blackband ironstone and potential water power; the development of new technologies, among them the steam engine and markets that would buy Scottish products. Other factors that also contributed to the process included the improvement of transport links, which helped facilitated the movement of goods, an extensive banking system, and the widespread adoption of ideas about economic development with their origins in the Scottish Enlightenment.[2]

Enlightenment

In the eighteenth century, the Scottish Enlightenment brought the country to the front of intellectual achievement in Europe.[3] The focus of the Scottish Enlightenment ranged from intellectual and economic matters to the specifically scientific. Adam Smith developed and published The Wealth of Nations, the first work of modern economics. It had an immediate impact on British economic policy and still frames discussions on globalisation and tariffs.[4] Key scientific work included the discoveries of William Cullen, physician and chemist; James Anderson, an agronomist; Joseph Black, physicist and chemist; and James Hutton, the first modern geologist.[5] While the Scottish Enlightenment is traditionally considered to have concluded toward the end of the eighteenth century,[6] disproportionately large Scottish contributions to British science and letters continued for another 50 years or more, thanks to such figures as James Hutton, James Watt, William Murdoch, James Clerk Maxwell and Lord Kelvin.[7]

Agricultural revolution

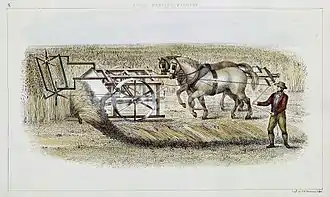

After the union with England in 1707, there was a conscious attempt among the gentry and nobility to improve agriculture in Scotland. The Society of Improvers was founded in 1723, including in its 300 members dukes, earls, lairds and landlords.[8] In the first half of the century these changes were limited to tenanted farms in East Lothian and the estates of a few enthusiasts, such as John Cockburn and Archibald Grant. Not all were successful, with Cockburn driving himself into bankruptcy, but the ethos of improvement spread among the landed classes.[9] Haymaking was introduced along with the English plough and foreign grasses, the sowing of rye grass and clover. Turnips and cabbages were introduced, lands enclosed and marshes drained, lime was put down, roads built and woods planted. Drilling and sowing and crop rotation were introduced. The introduction of the potato to Scotland in 1739 greatly improved the diet of the peasantry. Enclosures began to displace the runrig system and free pasture. There was increasing specialisation, with the Lothians became a major centre of grain, Ayrshire of cattle breading and the borders of sheep.[8] Although some estate holders improved the quality of life of their displaced workers,[8] the Agricultural Revolution led directly to what is increasingly known as the Lowland Clearances,[10] when hundreds of thousands of cottars and tenant farmers from central and southern Scotland were forcibly moved from the farms and small holdings their families had occupied for hundreds of years.[8] Improvement continued in the nineteenth century. Innovations included the first working reaping machine, developed by Patrick Bell in 1828. His rival James Smith turned to improving sub-soil drainage and developed a method of ploughing that could break up the subsoil barrier without disturbing the topsoil. Previously unworkable low-lying carselands could now be brought into arable production and the result was the even Lowland landscape that still predominates.[11] The development of Scottish agriculture meant that Scotland could support its increased population with food and it released labour that would take part in industrial production.[2]

Banking

The first banks formed in Scotland were the Bank of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1695) and the Royal Bank of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1727).[12] Glasgow would soon follow with branches of its own (notably, the first was to be Dunlop, Houston & Co. in 1749, known as "the Ship Bank" for the image of a ship printed on all their bills)[13] and Scotland had a flourishing financial system by the end of the century. There were over 400 branches, amounting to one office per 7,000 people, double the level in England. The banks were more lightly regulated than those in England. Historians often emphasise that the flexibility and dynamism of the Scottish banking system contributed significantly to the rapid development of the economy in the nineteenth century.[14][15] As a joint-stock company the British Linen Company had the right to raise funds through the issue of promissory notes or bonds. With its bonds functioning as bank notes, the company gradually moved into the business of lending and discounting to other linen manufacturers, and in the early 1770s banking became its main activity.[16]

Transport

The extensive Scottish coastline meant that few parts of the country that were not within easy reach of sea transportation, particularly the central belt that would be the heartland of industrial development. Before the eighteenth century most roads were relatively poor dirt tracks. In the late eighteenth century there were improvements carried out by turnpike trusts and the creation of a series of military roads.[2] Canal building also developed, with four major lowland canals: the Forth and Clyde, Union, Monkland and Crinan and further north the Paisley, Caledonian and Inverurie canals, carrying thousands of passengers and tons of goods by the early nineteenth century.[17]

Exports

With tariffs with England abolished, the potential for trade for Scottish merchants was considerable, especially with Colonial America. However, the economic benefits of union were very slow to appear, primarily because Scotland was too poor to exploit the opportunities of the greatly expanded free market. Scotland in 1750 was still a poor rural, agricultural society with a population of 1.3 million.[18] Furthermore, Scotland's economy had been ravaged by the Darien scheme: according to some estimates, half of all the circulating wealth in Scotland went into the scheme. Glasgow merchants had been particularly enthusiastic, and consequently had no ships of their own for twenty years following the disaster.[19] Some progress was visible, such as the sales of linen and cattle to England, the cash flows from military service, and the tobacco trade that was dominated by Glasgow after 1740. The clippers belonging to the Glasgow Tobacco Lords were the fastest ships on the route to Virginia.[20] The trade had started as smuggling during the 1600s, but with the Act of Union, it became legal and trade picked up.[21] Merchants who profited from the American trade began investing in leather, textiles, iron, coal, sugar, rope, sailcloth, glassworks, breweries, and soapworks, setting the foundations for the city's emergence as a leading industrial centre after 1815.[22] The tobacco trade collapsed during the American Revolution (1776–1783), when its sources were cut off by the British blockade of American ports. However, trade with the West Indies began to make up for the loss of the tobacco business,[23] reflecting the extensive growth of the cotton industry, the British demand for sugar and the demand in the West Indies for herring and linen goods. During 1750–1815, 78 Glasgow merchants not only specialised in the importation of sugar, cotton, and rum from the West Indies, but diversified their interests by purchasing West Indian plantations, Scottish estates, or cotton mills. They were not to be self-perpetuating due to the hazards of the trade, the incident of bankruptcy, and the changing complexity of Glasgow's economy.[24] Other burghs also benefited. Greenock enlarged its port in 1710 and sent its first ship to the Americas in 1719, but was soon playing a major part in importing sugar and rum.[25]

Linen

Linen manufacture was Scotland's premier industry in the eighteenth century and formed the basis for the later cotton, jute,[26] and woollen industries.[27] Scottish industrial policy was made by the Board of Trustees for Fisheries and Manufactures in Scotland, which sought to build an economy complementary, not competitive, with England. Since England had woolens, this meant linen.[28] The Scottish members of parliament managed to see off an attempt to impose an export duty on linen and from 1727 it received subsidies of £2,750 a year for six years, resulting in a considerable expansion of the trade. Paisley adopted Dutch methods and became a major centre of production. Glasgow manufactured for the export trade, which doubled between 1725 and 1738.[29]

Encouraged and subsidised by the Board of Trustees, so that they could compete with German products, merchant entrepreneurs became dominant in all stages of linen manufacturing and built up the market share of Scottish linens, especially in the American colonial market.[28] The British Linen Company, established in 1746, was the largest firm in the Scottish linen industry in the eighteenth century, exporting linen to England and America.[16] In 1728, 2.2 million yards of linen cloth had been produced and by 1730 it had already supplanted woollen cloth as the major manufacturing industry. By 1750 it reached 7.6 million and it peaked at 12.1 million yards in 1775. However, there were sharp slumps, particularly in the periods 1734–43 and 1763–72. It was a mainly rural industry, with most of the manufacture carried out in homes, rather than factories. It employed perhaps 100,000 people, four out of five of which were women who spun the flax, while men operated the looms.[30]

The government promoted the use of linen from the late 17th century: a 1686 Act of Parliament stated that all Scots were to be buried in Scottish-made linen winding sheets, using Scottish flax. In 1748, an embargo on the import or use of French cambric provided a further boost to the linen industry.[21] By 1770, Glasgow was the largest linen manufacturer in Britain, and in 1787, Calton, Glasgow was the site of Scotland's first industrial dispute when 7,000 weavers went on strike in protest against a 25% cut in their wages. The 39th Foot were sent in, and three people were killed.[31]

Sheer linen, which had then come into vogue, was almost unobtainable in Scotland in the 1780s. In a bid to stay competitive, Glasgow manufacturers turned to fine cotton muslin, at which they succeeded so well that it became cheaper than imported Indian muslins.[32] With the popularity of Indian muslins, from the 1760s onwards, had come a fashion for tambour lace, or sewed muslin, which briefly became a flourishing business in Ayrshire, thanks to the enterprising spirit of Mrs Jamieson.

Nineteenth century

.jpg.webp)

The economy, long based on agriculture,[18] began to industrialize after 1790. At first the leading industry, based in the west, was the production of cotton. After the cutting off of supplies of raw cotton from 1861 as a result of the American Civil War the country diversified into engineering, shipbuilding, and locomotive construction, with steel replacing iron after 1870.[33]

Cotton

From about 1790 textiles became the most important industry in the west of Scotland, especially the spinning and weaving of cotton. The first cotton spinning mill was opened at Penicuik in 1778. By 1787 Scotland had 19 mills, 95 by 1795 and there were 192 by 1839. The rise of cotton was the result of a sudden fall in the price of the raw materials because of slavery, mostly imported from the US, and the availability of a pool of cheap labour caused by population rise and migration. In 1775 137,000 lb of raw cotton were being imported into the Clyde and by 1812 it had increased eightfold to over 11 million lb. The capital invested in the industry increased sevenfold between 1790 and 1840.[34] By 1800, cotton was the main industry in the Glasgow area: New Lanark mills were at the time the largest in the world.[35] Early production was aided by the new technology of the spinning mule, water frame and water power.[2] Steam powered machines were introduced into the industry from 1782.[34] However, only about a third of workers were employed in factories and it continued to rely heavily on the hand loom weaver, working in his own home. In 1790 there were about 10,000 weavers involved in cotton manufacture and by 1800 it was 50,000.[36] The cotton industry flourished until in 1861 the American Civil War cut off the supplies of raw cotton.[37] The industry never recovered, but by that time Scotland had developed heavy industries based on its coal and iron resources.[38]

Coal

Coal mining became a major industry, and continued to grow into the twentieth century, producing the fuel to smelt iron, heat homes and factories and drive steam engines locomotives and steamships. Coal mining expanded rapidly in the eighteenth century, reaching 700,000 tons a year by 1750. Most coal was in five fields across the Central Belt. The first Newcomen Steam Engine was introduced into a Scottish colliery in 1719, but water remained the most important source of power for most of the century. With increased demand for household fuel from a growing urban population and the emerging demands of heavy industry, production grew from an estimated 1 million tons a year in 1775, to 3 million by 1830.[39] Production almost doubled by the 1840s and peaked in 1914 at about 42 million tons a year.[40]

Initially increased production was made possible by the introduction of cheap labour, provided from the 1830s by large numbers of Irish immigrants.[41] There were then changes in mining practices, which included the introduction of blasting powder in the 1850s and the use of mechanised methods of transferring the coal to the surface,[42] along with the introduction of steam power in the 1870s.[41] Landed proprietors were replaced by profit-seeking leasehold partnerships and joint-stock companies, whose members were often involved in the emerging iron industry.[39] By 1914 there were a million coal miners in Scotland. The stereotype emerged early on of Scottish colliers as brutish, non-religious and socially isolated serfs;[43] that was an exaggeration, for their life style resembled coal miners everywhere, with a strong emphasis on masculinity, egalitarianism, group solidarity, and support for radical labour movements.[44]

Iron and steel

The invention of James Beaumont Neilson's hot blast process for smelting iron in 1828 revolutionised the Scottish iron industry, allowing abundant native blackstone iron ore to be smelted with ordinary coal.[2] In 1830 Scotland had 27 iron furnaces and by 1840 it was 70, 143 in 1850 and it peaked at 171 in 1860.[45] Output was over 2,500,000 tons of iron ore in 1857, 6.5 per cent of UK output. Output of pig iron rose from 797,000 tons in 1854 to peak at 1,206,00 in 1869.[46] As a result, Scotland became a centre for engineering, shipbuilding and the production of locomotives.[38] In the 1871 census, the workforce in heavy industry overtook textiles in the Strathclyde region and in 1891 it became the majority employer in the country. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, steel production largely replaced iron production.[45]

Railways

Britain was the world leader in the construction of railways, and their use to expand trade and coal supplies. The first successful locomotive-powered line in Scotland, between Monkland and Kirkintilloch, opened in 1826. By the late 1830s there was a network of railways that included lines between Dundee and Arbroath, and connecting Glasgow, Paisley and Ayr. The line between Glasgow and Edinburgh, largely designed for passenger transport, opened in 1842 and proved highly successful. By the mid-1840s the mania for railways had begun.[47] A good passenger service established by the late 1840s, and a network of freight lines reduced the cost of shipping coal, making products manufactured in Scotland competitive throughout Britain.[48] The North British Railway was formed in 1844 to link Edinburgh and eastern Scotland with Newcastle and the next year the Caledonian Railway began connecting Glasgow and the west to Carlisle. The creation of a dense network in the Lowlands with connections to England would take until the 1870s to complete.[49]

A series of amalgamations meant that five main companies operated 98 per cent of the system by the 1860s. The capital invested in Scottish railways was £26.6 million in 1859 and by 1900 it had reached £166.1 million. The floatation of railway companies was a major factor in the formation of the Scottish stock exchanges and the rise of share holding in Scotland and after the early stages drew in large amounts of English investment.[49] The travel time between Edinburgh or Glasgow and London was cut from 43 hours to 17 and by the 1880s it had been reduced to 8.[47] Railways opened the London market to Scottish beef and milk. They enabled the Aberdeen Angus to become a cattle breed of worldwide reputation.[48][50]

Shipbuilding

Shipbuilding on Clydeside (the river Clyde through Glasgow and other points) began when the first small yards were opened in 1712 at the Scott family's shipyard at Greenock.[51] Major firms included Denny of Dumbarton, Scotts Shipbuilding and Engineering Company of Greenock, Lithgows of Port Glasgow, Simon and Lobnitz of Renfrew, Alexander Stephen and Sons of Linthouse, Fairfield of Govan, Inglis of Pointhouse, Barclay Curle of Whiteinch, Connell and Yarrow of Scotstoun. Equally important were the engineering firms that supplied the machinery to drive these vessels, the boilers and pumps and steering gear – Rankin & Blackmore, Hastie's and Kincaid's of Greenock, Rowan's of Finnieston, Weir's of Cathcart, Howden's of Tradeston and Babcock & Wilcox of Renfrew.[52] The biggest customer was Sir William Mackinnon, who ran five shipping companies in the nineteenth century from his base in Glasgow.[53] The Vulcan works, owned by Robert Napier and Sons were the first to start the production of large passenger iron ships in the 1840s.[54]

In 1835 the Clyde produced only 5 per cent of the ship tonnage built in Britain. The transition from wooden to iron ships was an uneven one, with wooden ships still cheaper to build until around 1850 and the material continued to be used until the 1860s in ships with composite hulls, like the clipper the Cutty Sark, which was launched from Dumbarton in 1869. Cost also delayed the transition from iron to steel shipbuilding and as late as 1879 only 18,000 tons of steel-built shipping was launched on the Clyde, 10 per cent of all tonnage. A similar process occurred in means of propulsion with shifts from sail to steam and back again between the 1840s and the introduction of the more efficient steam turbine engine that became dominant in the mid-1880s. Tonnage increased by more than a factor of six between 1880 and 1914.[54] Production peaked during the First World War and the term "Clyde-built" became synonymous with industrial quality.[55]

Engineering architecture

The nineteenth century saw some major engineering projects including Thomas Telford's (1757–1834) stone Dean Bridge (1829–31) and iron Craigellachie Bridge (1812–14).[56] In the 1850s the possibilities of new wrought- and cast-iron construction were explored in the building of commercial warehouses in Glasgow. This adopted a round-arched Venetian style first used by Alexander Kirkland (1824–92) at the heavily ornamented 37–51 Miller Street (1854) and translated into iron in John Baird I's Gardner's Warehouse (1855–56), with an exposed iron frame and almost uninterrupted glazing. Most industrial buildings avoided this cast-iron aesthetic, like William Spence's (1806?–83) Elgin Engine Works built in 1856–58, using massive rubble blocks.[57]

The most important engineering project was the Forth Bridge, a cantilever railway bridge over the Firth of Forth in the east of Scotland, 14 kilometres (9 mi) west of central Edinburgh. Construction of a suspension bridge designed by Thomas Bouch (1822–80), was stopped after the collapse of another of his works, the Tay Bridge in 1847.[58] The project was taken over by John Fowler (1817–98) and Benjamin Baker (1840–1907), who designed a structure that was built by Glasgow-based company Sir William Arrol & Co. from 1883. It was opened on 4 March 1890, and spans a total length of 2,528.7 metres (8,296 ft). It was the first major structure in Britain to be constructed of steel;[59] its contemporary, the Eiffel Tower was built of wrought iron.[60]

Impact

Population and urbanisation

The census conducted by the Reverend Alexander Webster in 1755 showed the inhabitants of Scotland as 1,265,380 persons.[61] By the time of the first decadal census in 1801, the population was 1,608,420. It grew steadily in the nineteenth century, to 2,889,000 in 1851 and 4,472,000 in 1901.[62]

While population fell in some rural areas as a result of the agricultural revolution, it rose rapidly in the towns. Aberdeen, Dundee and Glasgow all grew by a third or more between 1755 and 1775 and the textile town of Paisley more than doubled its population.[34] Scotland was already one of the most urbanised societies in Europe by 1800.[63] In 1800, 17 per cent of people in Scotland lived in towns of more than 10,000 inhabitants. By 1850 it was 32 per cent and by 1900 it was 50 per cent. By 1900 one in three of the entire population were in the four cities of Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee and Aberdeen.[64]

Glasgow emerged as the largest city. Its population in 1780 was 43,000, reaching 147,000 by 1820; by 1901 it had grown to 762,000. This was due to a high birth rate and immigration from the countryside and particularly from Ireland; but from the 1870s there was a fall in the birth rate and lower rates of migration and much of the growth was due to longer life expectancy.[64] Glasgow was now one of the largest cities in the world, and it became known as "the Second City of the Empire" after London.[65]

Dundee upgraded its harbour and established itself as an industrial and trading centre. Dundee's industrial heritage was based on "the three Js": jute, jam and journalism. East-central Scotland became too heavily dependent on linens, hemp, and jute. Despite the cyclical nature of the trade which periodically ruined weaker companies, profits held up well in the nineteenth century. Typical firms were family affairs, even after the introduction of limited liability in the 1890s. The profits helped make the city an important source of overseas investment, especially in North America. However, the profits were seldom invested locally, apart from the linen trade. The reasons were that low wages limited local consumption, and because there were no important natural resources; thus the Dundee region offered little opportunity for profitable industrial diversification.[66]

The industrial developments, while they brought work and wealth, were so rapid that housing, town-planning, and provision for public health did not keep pace with them, and for a time living conditions in some of the towns and cities were notoriously bad, with overcrowding, high infant mortality, and growing rates of tuberculosis.[67] Mortality rates were high compared with England and other European nations. Evidence suggests a national death rate of 30 per 1,000 in 1755, 24 in the 1790s and 22 in the early 1860s. Mortality tended to be much higher in urban than rural settlements. The first time these were measured, 1861–82, in the four major cities these were 28.1 per 1,000 and 17.9 in rural areas. Mortality probably peaked in Glasgow in the 1840s, when large inflows of population from the Highlands and Ireland combined population outgrowing sanitary provision and combining with outbreaks of epidemic disease. National rates began to fall in the 1870s, particularly in the cities, as environmental conditions improved.[68] The companies attracted rural workers, as well as immigrants from Catholic Ireland, by inexpensive company housing that was a dramatic move upward from the inner-city slums. This paternalistic policy led many owners to support government sponsored housing programs as well as self-help projects among the respectable working class.[69]

Class identity

One of the consequences of industrialisation and urbanisation was the development of a distinct skilled working class. W. H. Fraser argues that the emergence of a class identity can be located to the period before the 1820s, when cotton workers in particular were involved in a series of political protests and events. This led to the Radical War of 1820, in which a declaration of a provisional government by three weavers coincided with a strike by Glasgow cotton workers. The climax of the five-day war was a march from Glasgow Green to Falkirk to take control of the Carron Iron Works. It ended in a cavalry charge by government forces at Bonnymuir. The result was a discouragement of direct political action by workers, although attempts at political reform continued in movements like Chartism and the short hours movement in the 1830s.[70]

From the 1830s the political influence of the working classes was expanded through the widening of the franchise, industrial action and the growth and organisation of trade unionism. There were less than 5,000 eligible voters in Scotland before the 1832 Reform Act saw the enlargement of the franchise to include middle-class men of business. The 1868 Act brought in skilled artisans and that of 1884 admitted many farm workers, crofters, miners and unskilled men. These changes were supported by trade unions,[71] which developed from the mid-century. Concerted industrial action was undertaken by spinners in the cotton industry in 1836-7 after a collapse of foreign markets led to wage cuts, but was ultimately defeated by the factory owners. The most sustained industrial action was in the mining industry, where the owners controlled employment as well as housing and retail trade through the truck system. In 1887 colliers in the west of Scotland won a major victory over both wages and rents.[72] Scottish trade unionism in the nineteenth century differed from that in the rest of Britain in that unions were often small and highly localised and lacked higher industrial and national organisation.[73] Trade councils were established in Edinburgh in 1853 and in Glasgow in 1858 in an attempt to organise on a regional basis, but were often ineffectual.[74] The new unionism of the last two decades of the century saw the dockers and railwaymen organise a network of regional and national support, but this began to wain towards the end of the century and the situation of union parochialism would remain the dominant mode until union amalgamations got under way after 1914.[75]

Women

The industrialisation of Scotland had a major impact of the roles of women. Women and girls formed a much higher proportion of the workforce than elsewhere in Britain and were the majority of workers in some industries. The expansion of flax spinning and the rise of linen industry in the eighteenth century was almost totally dependent on female labour and the situation was similar in the sewed muslin industry in the West of Scotland towards the end of the century. When flax spinning became mechanised the proportion of men to women was 100:280, the highest proportion of women in the United Kingdom. In Dundee in the 1840s, while male employment increased by a factor of 1.6, female employment went up by 2.5, making it the only large town in Scotland with the majority of its female population in paid employment. In cotton in the nineteenth century women and girls accounted for 61 per cent of the workforce in Scottish mills, compared with 50 per cent in Lancashire. Although most women were employed in the textile industries, they were also a significant proportion of the workforce in other areas, making up 12 per cent of underground workers in mining, compared with 4 per cent in Britain overall.[76] The expanded opportunities for women, and the extra income they and children brought into the household, probably did the most to help increase living standards for working-class families.[77]

The role of women in workforce peaked in the 1830s. As heavy industry began to dominate there were less opportunities for women.[76] From the mid-nineteenth century there were a series of laws that limited female roles in industry, beginning with the Mines Regulation Act of 1842, which prevented them from working underground. This put 2,500 women out of work in the east of Scotland, causing real hardship as their contribution to the family economy was vital. This was followed by a series of factory acts that placed restrictions on the employment of women. Many of these acts were brought in because of pressure from trade unions who were attempting to secure a living wage for their male members. Women had relatively little involvement in official trade unions for much of the period of industrialisation. However, they were frequently involved in unofficial disputes, the first being recorded in 1768 and of which there are known to have been 300 strikes that involved women between 1850 and 1914. Towards the end of the century there were increasing attempts to unionise women. The Scottish Women's Trade Council (SWTC) was formed in 1887. From this emerged the Women's Protective and Provident League (WPPL) and the Glasgow Council for Women's Trades (GCWT). In 1893, the National Federal Council of Scotland for Women's Trades (NFCSWT) was established and the Scottish Council for Women's Trades (SCWT) in 1900. By 1895 the NFCSWT alone had an affiliated membership of 100,000.[78]

Migration

The growth of industry resulted in the arrival of large numbers of workers from Ireland who moved into the factories and mines in the 1830s and 1840s.[79] Many were seasonal workers employed as navvies on the construction of docks, canals and then railways.[80] An estimated 60–70 per cent of colliers in Lanarkshire were Irish by the 1840s. The arrivals intensified with the Great Famine of 1845.[79] By the census of 1841, 126,321, or 4.6 per cent of Scotland's population, had been born in Ireland and many more were of Irish descent. Most were concentrated in the west of Scotland, and in Glasgow there were 44,000 people who were born in Ireland, 16 per cent of the city's population.[81] Most Irish immigrants, about three quarters, were Catholic,[79] leading to a major cultural and religious change in Scotland, but a quarter were Protestant, eventually bringing with them institutions like the Orange Order and intensifying a sectarian divide in the major cities.[80]

Even with the growth of industry there were insufficient good jobs, which with major changes in agriculture, meant that during the period 1841–1931, about two million Scots emigrated to North America and Australasia, and another 750,000 Scots relocated to England.[82] Of those who migrated to non-European locations in the century before 1914, 44 per cent went to the US, 28 per cent to Canada, and 25 per cent to Australia and New Zealand. Other important locations included the Caribbean, India and South Africa.[83] By the twenty-first century, there were about as many people who were Scottish Canadians and Scottish Americans as the five million remaining in Scotland.[82] There was little support from the government and in the early stages many migrants agreed to indentures, particularly to the Thirteen Colonies, that paid for their passage and guaranteed accommodation and work for five or seven years. Later immigration was assisted by agents and societies, such as the Salvation Army, Barnados and the Aberdeen Ladies Union, who often focused on the young or female immigrants.[83]

Notes

- T. C. Smout, "The Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707. I: The Economic Background", Economic History Review, New Series, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 455–67 in JSTOR

- R. Finley, "4. Economy: 1770–1850 age of industrialization", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 198–9.

- A. Herman, How the Scots Invented the Modern World (London: Crown Publishing Group, 2001), ISBN 0-609-80999-7.

- M. Fry, Adam Smith's Legacy: His Place in the Development of Modern Economics (London: Routledge, 1992), ISBN 0-415-06164-4.

- J. Repcheck, The Man Who Found Time: James Hutton and the Discovery of the Earth's Antiquity (Cambridge, MA: Basic Books, 2003), ISBN 0-7382-0692-X, pp. 117–43.

- M. Magnusson (10 November 2003), "Review of James Buchan, Capital of the Mind: How Edinburgh Changed the World", New Statesman, archived from the original on 6 June 2011.

- E. Wills, Scottish Firsts: a Celebration of Innovation and Achievement (Edinburgh: Mainstream, 2002), ISBN 1-84018-611-9.

- J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 288–91.

- I. D. Whyte, "Economy: primary sector: 1 Agriculture to 1770s", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 206–7.

- Robert Allan Houston and Ian D. Whyte, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-521-89167-1, pp. 148–151.

- G. Sprot, "Agriculture, 1770s onwards", in M. Lynch, ed., Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), ISBN 0199693056, pp. 321–3.

- R. Saville, Bank of Scotland: a History, 1695–1995 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press 1996), ISBN 0-7486-0757-9.

- Michael Meighan, Glasgow: A History (Amberley Publishing, 2013), p. 22.

- M. J. Daunton, Progress and Poverty: An Economic and Social History of Britain 1700–1850 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), ISBN 0-19-822281-5, p. 344.

- T. Cowen and R. Kroszner, "Scottish Banking before 1845: A Model for Laissez-Faire?", Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, vol. 21 (2), (May, 1989), pp. 221–31, in JSTOR.

- C. A. Malcolm, The History of the British Linen Bank (Edinburgh: T. & A. Constable, 1950), ISBN 1446526283.

- A. J. Durie, "Movement, transport and tourism" in T. Griffiths and G. Morton, eds, A History of Everyday Life in Scotland, 1800 to 1900 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010), ISBN 0748621709, p. 149.

- H. Hamilton, An Economic History of Scotland in the Eighteenth Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963).

- Alan Massie, Glasgow: Portraits of a City (Barrie & Jenkins, 1989), p. 21-2.

- M. Lester, "The Tobacco Lords: A study of the Tobacco Merchants of Glasgow and their Activities", Virginia Historical Society Vol. 84, No. 1 (1976), in JSTOR, p. 100.

- Michael Meighan, Glasgow: A History (Amberley Publishing, 2013), p. 21.

- T. M. Devine, "The Colonial Trades and Industrial Investment in Scotland, c. 1700–1815," Economic History Review, Feb 1976, vol. 29 (1), pp. 1–13.

- R. H. Campbell, "The Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707. II: The Economic Consequences," Economic History Review, April 1964 vol. 16, pp. 468–477 in JSTOR.

- T. M. Devine, "An Eighteenth-Century Business Élite: Glasgow-West India Merchants, c 1750–1815," Scottish Historical Review, April 1978, vol. 57 (1), pp. 40–67.

- J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, p. 296.

- L. Miskell and C. A. Whatley, "'Juteopolis' in the Making: Linen and the Industrial Transformation of Dundee, c. 1820–1850," Textile History, Autumn 1999, vol. 30 (2), pp. 176–98.

- A. J. Durie, "The Markets for Scottish Linen, 1730–1775", Scottish Historical Review vol. 52, no. 153, Part 1 (April, 1973), pp. 30–49 in JSTOR.

- Alastair Durie, "Imitation in Scottish Eighteenth-Century Textiles: The Drive to Establish the Manufacture of Osnaburg Linen," Journal of Design History, 1993, vol. 6 (2), pp. 71–6.

- J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 292–3.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0, p. 381.

- Michael Meighan, Glasgow: A History (Amberley Publishing, 2013), p. 47.

- Margaret Swain, Scottish Embroidery: Medieval to Modern (BT Batsford, 1986), p. 95.

- O. Checkland and S. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd ed., 1989), ISBN 0748601023, p. 26.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0712698930, p. 383.

- Michael Meighan, Glasgow: A History (Amberley Publishing, 2013), p. 48.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0, p. 384.

- W. O. Henderson, The Lancashire Cotton Famine 1861–65 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1934), p. 122.

- C. A. Whatley, The Industrial Revolution in Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), ISBN 0-521-57643-1, p. 51.

- I. D. Whyte, "Economy: primary sector: 1 industry to 1770s", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 211–12.

- C. A. Whatley, "Economy: primary sector: 3 mining and quarrying", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 208–9.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0, p. 408.

- W. Knox, Industrial Nation: Work, Culture and Society in Scotland, 1800–present (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Series, 1999), ISBN 0748610855, p. 105.

- C. A. Whatley, "Scottish 'collier serfs', British coal workers? Aspects of Scottish collier society in the eighteenth century", Labour History Review, Fall 1995, vol. 60 (2), pp. 66–79.

- A. Campbell, The Scottish Miners, 1874–1939 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), ISBN 0-7546-0191-9.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0, p. 407.

- O. Checkland and S. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd ed., 1989), ISBN 0748601023, pp. 24–5.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0, p. 410.

- O. Checkland and S. G. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland, 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 1989), ISBN 0-7486-0102-3, pp. 17–52.

- O. Checkland and S. G. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland, 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 1989), ISBN 0-7486-0102-3, pp. 26–7.

- W. Vamplew, "Railways and the Transformation of the Scottish Economy", Economic History Review, Feb 1971, vol. 24 (1), pp. 37–54.

- J. Shields, Clyde Built: a History of Ship-Building on the River Clyde (Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1949).

- R. Johnston, Clydeside Capital, 1870–1920: a Social History of Employers (Tuckwell Press, 2000), ISBN 1862321027.

- J. Forbes Munro, Maritime Enterprise and Empire: Sir William Mackinnon and His Business Network, 1823–1893 (Boydell Press, 2003), ISBN 0851159354, p. 494.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0, p. 409.

- R. Finley, "Economy: 5 1850–1918, The Mature Economy", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 199–200.

- C. Harvie, Scotland: A Short History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-19-210054-8, p. 133.

- M. Glendinning, R. MacInnes and A. MacKechnie, A History of Scottish Architecture: from the Renaissance to the Present Day (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2002), ISBN 978-0-7486-0849-2, p. 254.

- I. B. Whyte, A. J. MacDonald and C. Baxter, John Fowler, Benjamin Baker, Forth Bridge (Axel Menges, 2nd edn., 1997), ISBN 3-930698-18-8, p. 7.

- A. Blanc, M. McEvoy and R. Plank, Architecture and Construction in Steel (London: Taylor & Francis, 1993), ISBN 0-419-17660-8, p. 16.

- J. E. McClellan and H. Dorn, Science And Technology in World History: An Introduction (JHU Press, 2nd edn., 2006), ISBN 0-8018-8360-1, p. 315.

- K. J. Cullen, Famine in Scotland: The "Ill Years" of the 1690s (Edinburgh University Press, 2010), ISBN 0-7486-3887-3, pp. 123–4.

- A. K. Cairncross, The Scottish Economy: A Statistical Account of Scottish Life by Members of the Staff of Glasgow University (Glasgow: Glasgow University Press, 1953), p. 10.

- W. Ferguson, The Identity of the Scottish Nation: An Historic Quest (1998) online edition.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0712698930, pp. 411–12.

- J. F. MacKenzie, "The second city of the Empire: Glasgow – imperial municipality", in F. Driver and D. Gilbert, eds, Imperial Cities: Landscape, Display and Identity (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-7190-6497-X, pp. 215–23.

- B. Lenman and Kathleen Donaldson, "Partners' Incomes, Investment and Diversification in the Scottish Linen Area 1850–1921", Business History, Jan 1971, vol. 13(1), pp. 1–18.

- C. H. Lee, Scotland and the United Kingdom: the Economy and the Union in the Twentieth Century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), ISBN 0-7190-4101-5, p. 43.

- M. Anderson, "Population patterns: 2 since 1770, in M. Lynch, ed., Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), ISBN 0-19-969305-6, pp. 489–91.

- J. Melling, "Employers, industrial housing and the evolution of company welfare policies in Britain's heavy industry: west Scotland, 1870–1920", International Review of Social History, Dec 1981, vol. 26 (3), pp. 255–301.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0, pp. 390–1.

- O. Checkland and S. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd ed., 1989), ISBN 0748601023, p. 66.

- O. Checkland and S. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd ed., 1989), ISBN 0748601023, pp. 86–8.

- W. Kenefick, Red Scotland!: The Rise and Fall of the Radical Left, c. 1872–1932 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748625186, p. 8.

- O. Checkland and S. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd ed., 1989), ISBN 0748601023, p. 89.

- W. Kenefick, Red Scotland!: The Rise and Fall of the Radical Left, c. 1872–1932 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748625186, p. 9.

- C. A. Whatley, The Industrial Revolution in Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), ISBN 0521576431, pp. 74–5.

- C. A. Whatley, The Industrial Revolution in Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), ISBN 0521576431, p. 83.

- Y. Brown, "Women: 1770s onwards", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), ISBN 0199234825, pp. 647–50.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0, p. 395.

- J. McCaffery, "Immigration, Irish", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 331–3.

- W. Knox, Industrial Nation: Work, Culture and Society in Scotland, 1800–present (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999), ISBN 0748610855, p. 37.

- R. A. Houston and W. W. Knox, eds, The New Penguin History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 2001), ISBN 0-14-026367-5, p. xxxii.

- M. D. Harper, "Emigration: 4 post-1750, excluding Highlands", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 232–4.