Scottish education in the nineteenth century

Scottish education in the nineteenth century concerns all forms of education, including schools, universities and informal instruction, in Scotland in the nineteenth century. By the late seventeenth century there was a largely complete system of parish schools, but it was undermined by the Industrial Revolution and rapid urbanisation. The Church of Scotland, the Free Church of Scotland and the Catholic church embarked on programmes of school building to fill in the gaps in provision, creating a fragmented system. Attempts to supplement the parish system included Sunday schools, mission schools, ragged schools, Bible societies and improvement classes. Scots played a major part in the development of teacher education with figures including William Watson, Thomas Guthrie, Andrew Bell, John Wood and David Stow. Scottish schoolmasters gained a reputation for strictness and frequent use of the tawse. The perceived problems and fragmentation of the Scottish school system led to a process of secularisation, as the state took increasing control. The Education (Scotland) Act 1872 transferred the Kirk and Free Kirk schools to regional School Boards and made some provision for secondary education. In 1890 school fees were abolished, creating a state-funded, national system of compulsory free basic education with common examinations.

_(3816540623).jpg.webp)

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Scotland's five university colleges had no entrance exams, students typically entered at ages of 15 or 16, attended for as little as two years, chose which lectures to attend and left without qualifications. The curriculum was dominated by divinity and the law. There was a concerted attempt to modernise the curriculum resulting in reforming acts of parliament in 1858 and 1889. The curriculum and system of graduation were reformed, entrance examinations introduced and average ages of entry rose to 17 or 18. There was a revitalisation of the Scottish university system, which expanded to 6,254 students by the end of the century. Major figures produced by the university system included William John Macquorn Rankine, Thomas Thomson, William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, David Brewster, Fleeming Jenkin, Joseph Lister, William Macewen, Robert Jameson, Edward Caird, James George Frazer and Patrick Geddes.

Schools

Background: the school system

After the Reformation there were a series of attempts to provide a network of parish schools throughout Scotland. By the late seventeenth century this was largely complete in the Lowlands, but in the Highlands elementary education was still lacking in many areas.[1] These schools were controlled by the local Church of Scotland and provided a basic education, mainly to boys.[2] By the eighteenth century many poorer girls were being taught in dame schools, informally set up by a widow or spinster to teach reading, sewing, and cooking.[3] The Statistical Account of Scotland undertaken parish-by-parish by John Sinclair in the 1790s indicated that all but the oldest inhabitants were expected to be able to read and that many (although fewer girls) could write and count. However, it also indicated that much of the legal provision of schooling had often fallen into decay.[2] In the burghs there were a range or parish schools, burgh schools and grammar schools, most of which provided a preparation for one of the Scottish universities. These were supplemented by boarding establishments, known as "hospitals", most of which had been endowed by charities, such as George Heriot's School and the Merchant Companies Schools in Edinburgh.[4] The Industrial Revolution and rapid urbanisation undermined the effectiveness of the Scottish church school system, creating major gaps in provision and religious divisions would begin to undermine the unity of the system.[5] The publication of George Lewis's Scotland: a Half Educated Nation in 1834 began a major debate on the suitability of the parish school system, particularly in rapidly expanding urban areas.[6]

Church schools

Aware of the growing shortfall in provision the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland formed an education committee in 1824. The committee had established 214 "assembly schools" by 1865. There were also 120 "sessional schools", mainly established by kirk sessions in towns and aimed at the children of the poor.[7] The Disruption of 1843, which created the breakaway Free Church of Scotland, fragmented the kirk school system. 408 teachers in schools joined the breakaway Free Church. By May 1847 it was claimed that 500 schools had been built, along with two teacher training colleges and a ministerial training college,[8] 513 schoolmasters were being paid direct from a central education fund and over 44,000 children being taught in Free Church schools.[9] The influx of large numbers of Irish immigrants in the nineteenth century led to the establishment of Catholic schools, particularly in the urban west of the country, beginning with Glasgow in 1817.[10] The church schools system was now divided between three major bodies, the established Kirk, the Free Church and the Catholic Church.[7]

Supplementary education

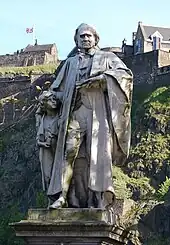

Attempts to supplement the parish system included Sunday schools. Originally begun in the 1780s by town councils, they were adopted by all religious denominations in the nineteenth century. The movement peaked in the 1890s. By 1890 the Baptists had more Sunday schools than churches and were teaching over 10,000 children.[11] In 1895, 50,000 teachers were working within the Church of Scotland in these schools[12] and 60 per cent of children aged 5–15 in Glasgow were enrolled on their books.[13] From the 1830s and 1840s there were also mission schools, ragged schools, Bible societies and improvement classes, open to members of all forms of Protestantism and particularly aimed at the growing urban working classes.[11] The ragged school movement attempted to provide free education to destitute children. The ideas were taken up in Aberdeen where Sheriff William Watson founded the House of Industry and Refuge, and they were championed by Scottish minister Thomas Guthrie who wrote Plea for Ragged Schools (1847), after which they rapidly spread across Britain.[14]

Theory and practice

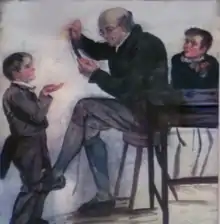

Scots played a major part in the development of teacher education. Andrew Bell (1753–1832) pioneered the Monitorial System, by which the more able pupils would pass on the information they had learned to other children and which developed into the pupil-teacher system of training. It was further developed by John Wood, Sheriff-Depute of Peebles, who tended to favour fierce competition in the classroom and strict discipline. In contrast David Stow (1793–1864), who founded the first infant school in Scotland, in Glasgow in 1828, focused on the bond between teacher and child and advocated the "Glasgow method", which centred on trained adult teachers.[4] He established the first teacher training college in the United Kingdom, the Glasgow Normal Seminary. When, after the Great Disruption it was declared the property of the Church of Scotland, he founded the Free Church Normal Seminary in 1845.[15] Ultimately Wood's ideas played a greater role in the Scottish educational system as they fitted with the need for rapid expansion and low costs that resulted from the reforms of 1872.[4] Scottish schoolmasters gained a reputation for strictness and frequent use of the tawse, a belt of horse hide split at one end that inflicted stinging punishment on the hands of pupils.[16]

Commissions

The perceived problems and fragmentation of the Scottish school system led to a process of secularisation, as the state took increasing control. From 1830 the state began to fund buildings with grants, then from 1846 it was funding schools by direct sponsorship.[17] The 1861 Education Act removed the provision stating that Scottish teachers had to be members of the Church of Scotland or subscribe to the Westminster Confession. In 1866 the government established the Argyll Commission, under Whig grandee George Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll, to look into the schooling system. It found that of 500,000 children in need of education 200,000 were receiving it under efficient conditions, 200,000 in schools of doubtful merit, without any inspection and 90,000 were receiving no education at all. Although this compared favourably with the situation in England, with 14 per cent more children in education and with relatively low illiteracy rates of between 10 and 20 per cent, similar to those in the best educated nations such as those in Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Scandinavia, the report was used as support for widespread reform. The result was the Education (Scotland) Act 1872, based on that passed for England and Wales as the Elementary Education Act in 1870, but providing a more comprehensive solution.[18]

1872 act

Under the Education (Scotland) Act 1872 approximately 1,000 regional School Boards were established[19] and, unlike in England where they merely attempted to fill gaps in provision, immediately took over the schools of the old and new kirks and were able to begin to enforce attendance, rather than after the decade necessary in England.[18] Some ragged and industrial schools requested to be taken over by the boards, while others continued as Sunday schools.[14] All children aged from 5 to 13 years were to attend. Poverty was not accepted as an excuse and some help was supplied under the poor law. This was enforced by the School Attendance Committee, while the boards busied themselves with building to fill the gaps in provision. This resulted in a major programme that created large numbers of grand, purpose-built schools.[18] Overall administration was in the hands of the Scotch (later Scottish) Education Department in London.[17] Demand for places was high and for a generation after the act there was overcrowding in many classrooms, with up to 70 children being taught in one room. The emphasis on a set number of passes at exams also led to much learning by rote and the system of inspection led to even the weakest children being drilled with certain facts.[18]

To compensate for the difficult of educating children in the sparesly populated Highlands, in 1885 the Highland Minute established a subsidy for such schools.[20]

Secondary education

Unlike the English act, the Scottish one made some provision for secondary education.[4] The Scottish Education Department intended to expand secondary education, but did not intend to produce a universal system. The preferred method was to introduce vocational supplementary teaching in the elementary schools, later known as advanced divisions, up until the age of 14, when pupils would leave to find work. This was controversial because it seemed to counter the cherished principle that schooling was a potential route to university for the bright "lad o' parts".[19] Larger urban school boards established about 200 "higher grade" (secondary) schools as a cheaper alternative to the burgh schools.[1][19] Some of these were former grammar schools, such as the Glasgow and Edinburgh High Schools, Aberdeen New High School and Perth Academy. Some hospitals became day schools and largely remained independent, while a few, including Fettes College in Edinburgh, became public schools on the English model. Other public schools emerged around the mid century, such as Merchiston, Loretto School and Trinity College, Glenalmond.[4] The result of these changes was a fear that secondary education became much harder to access for the children of the poor.[19] However, in the second half of the century roughly a quarter of university students can be described as having working class origins, largely from the skilled and independent sectors of the economy.[19] The Scottish Education Department introduced a Leaving Certificate Examination in 1888 to set national standards for secondary education. In 1890 school fees were abolished, creating a state-funded, national system of compulsory free basic education with common examinations.[1]

Universities

Background: the ancient universities

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Scotland's five university colleges had about 3,000 students between them.[21] They had no entrance exam, students typically entered at ages of 15 or 16, attended for as little as two years, chose which lectures to attend and left without qualifications.[22] Although Scottish universities had gained a formidable reputation in the eighteenth century, particularly in areas like medicine and had produced leading scientists such as Joseph Black (1728–99), the curriculum was dominated by divinity and the law and there was a concerted attempt to modernise the curriculum, particularly by introducing degrees in the physical sciences and the need to reform the system to meet the needs of the emerging middle classes and the professions.[22] The result was two commissions of inquiry in 1826 and 1876 and reforming acts of parliament in 1858 and 1889.[22]

Reforms

The curriculum and system of graduation were reformed. Entrance examinations equivalent to the School Leaving Certificate were introduced and average ages of entry rose to 17 or 18. Standard patterns of graduation in the arts curriculum offered 3-year ordinary and 4-year honours degrees.[22] There was resistance among professors, particularly among chairs of divinity and classics, to the introduction of new subjects, particularly the physical sciences. The crown established Regius chairs, all in the sciences, including medicine, chemistry, natural history and botany. The chair of Engineering at Glasgow was the first of its kind in the world. By the 1870s the physical sciences were well established in Scottish universities, whereas in England the battle would not be complete until the end of the century.[23] The new separate science faculties were able to move away from the compulsory Latin, Greek and philosophy of the old MA curriculum.[22] Under the commissions all the universities were restructured. They were given Courts, which included external members and who oversaw the finances of the institution. Under the 1889 act new arts subjects were established, with chairs in Modern History, French, German and Political Economy.[23]

The University of St Andrews was at a low point in its fortunes in the early part of the century. It was restructured by commissioners appointed by the 1858 act and began a revival.[23] It pioneered the admission of women to Scottish universities, creating the Lady Licentiate in Arts (LLA), which proved highly popular. From 1892 Scottish universities could admit and graduate women and the numbers of women at Scottish universities steadily increased until the early twentieth century.[24] The University of Glasgow became a leader in British higher education by providing the educational needs of youth from the urban and commercial classes.[25] It moved from the city centre to a new set of grand neo-Gothic buildings, paid for by public subscription, at Gilmorehill in 1870.[26] The two colleges at Aberdeen were considered too small to be viable and they were restructured as the University of Aberdeen in 1860.[23] A new college of the university was opened in Dundee in 1883.[21] Unlike the other Medieval and ecclesiastical foundations, the University of Edinburgh was the "tounis college", founded by the city after the Reformation, and was as a result relatively poor. In 1858 it was taken out of the care of the city and established on a similar basis to the other ancient universities.[23]

Achievements

The result of these reforms was a revitalisation of the Scottish university system, which expanded to 6,254 students by the end of the century[21] and produced leading figures in both the arts and sciences. The chair of Engineering at Glasgow became highly distinguished under its second incumbent William John Macquorn Rankine (1820–72), who held the position from 1859 to 1872 and became the leading figure in heat engines and founder president of the Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland.[23] Thomas Thomson (1773–1852) was the first professor of Chemistry at Glasgow and in 1831 founded the Shuttle Street laboratories, perhaps the first of their kind in the world. His students founded practical chemistry at Aberdeen soon after. William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin was appointed to the chair of natural philosophy at Glasgow aged only 22. His work included the mathematical analysis of electricity and formulation of the first and second laws of thermodynamics. By 1870 Kelvin and Rankine made Glasgow the leading centre of science and engineering education and investigation in Britain.[23]

At Edinburgh, major figures included David Brewster (1781–1868), who made contributions to the science of optics and to the development of photography. Fleeming Jenkin (1833–85) was the first professor of engineering at the university and among wide interests helped develop ocean telegraphs and mechanical drawing.[23] In medicine Joseph Lister (1827–1912) and his student William Macewen (1848–1924), pioneered antiseptic surgery.[27] The University of Edinburgh was also a major supplier of surgeons for the royal navy, and Robert Jameson (1774–1854), Professor of Natural History at Edinburgh, ensured that a large number of these were surgeon-naturalists, who were vital in the Humboldtian and imperial enterprise of investigating nature throughout the world.[28][29] Major figures to emerge from Scottish universities in the science of humanity included the philosopher Edward Caird (1835–1908), the anthropologist James George Frazer (1854–1941) and the sociologist and urban planner Patrick Geddes (1854–1932).[30]

Notes

- R. Anderson, "The history of Scottish education pre-1980", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1625-X, pp. 219–28.

- D. Witherington, "Schools and schooling: 2. 1697–1872", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 563–5.

- B. Gatherer, "Scottish teachers", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1625-X, p. 1022.

- O. Checkland and S. G. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland, 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0748601023, pp. 114–15.

- T. M. Devine, The Scottish Nation, 1700–2000 (London: Penguin Books, 2001), ISBN 0-14-100234-4, pp. 91–100.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0, p. 357.

- O. Checkland and S. G. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland, 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0748601023, p. 111.

- G. Parsons, "Church and state in Victorian Scotland: disruption and reunion", in G. Parsons and J. R. Moore, eds, Religion in Victorian Britain: Controversies (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988), ISBN 0719025133, p. 116.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (Random House, 2011), ISBN 1-4464-7563-8, p. 397.

- J. C. Conroy, "Catholic Education in Scotland", in M. A. Hayes and L. Gearon, eds, Contemporary Catholic Education (Gracewing, 2002), ISBN 0852445288, p. 23.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0712698930, p. 403.

- C. Brown, Religion and Society in Scotland Since 1707 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1997), ISBN 0748608869, p. 130

- D. W. Bebbington, "Missions at Home", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, p. 423.

- G. Morton, Ourselves and Others: Scotland 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012), ISBN 0748620494, p. 181.

- T. M. Devine, Glasgow: 1830 to 1912 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996), ISBN 0719036925, pp. 398–9.

- M. Peters, "Scottish education: an international perspective" in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003), ISBN 074861625X, p. 1024.

- "Education records", National Archive of Scotland, 2006, archived from the original on 31 August 2011

- O. Checkland and S. G. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland, 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0748601023, pp. 112–13.

- L. Patterson, "Schools and schooling: 3. Mass education 1872–present", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 566–9.

- "The Scottish Law Reporter: Containing Reports by ... of Cases Decided in the Court of Session, Court of Justiciary, Court of Teinds, and House of Lords". The Scottish Law Reporter: Containing Reports by ... Of Cases Decided in the Court of Session, Court of Justiciary, Court of Teinds, and House of Lords. XXIX: 205–206. 1892.

- R. D. Anderson, "Universities: 2. 1720–1960", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 612–14.

- R. Anderson, "The history of Scottish education pre-1980", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1625-X, p. 224.

- O. Checkland and S. G. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland, 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0748601023, pp. 147–50.

- M. F. Rayner-Canham and G. Rayner-Canham, Chemistry was Their Life: Pioneering British Women Chemists, 1880–1949 (London: Imperial College Press, 2008), ISBN 1-86094-986-X, p. 264.

- P. L. Robertson, "The Development of an Urban University: Glasgow, 1860–1914", History of Education Quarterly, Winter 1990, vol. 30 (1), pp. 47–78.

- T. M. Devine, Glasgow: 1830 to 1912 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996), ISBN 0719036925, p. 249.

- O. Checkland and S. G. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland, 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0748601023, p. 151.

- J. L. Heilbron, The Oxford Companion To the History of Modern Science (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), ISBN 0195112296, p. 386.

- J. Browne, "A science of empire: British biogeography before Darwin", Revue d'histoire des Sciences, vol. 45 (1992), p. 457.

- O. Checkland and S. G. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland, 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0748601023, pp. 152–4.