National symbols of Serbia

The national symbols of Serbia are things which are emblematic, representative or otherwise characteristic of Serbia and the Serbian people or Serbian culture. Some are established, official symbols; for example, the Coat of arms of Serbia, which has been codified in heraldry. Other symbols may not have official status, for one reason or another, but are likewise recognised at a national or international level.

Official symbols

| Type | Image | Symbol |

|---|---|---|

| National flag |  |

Flag of Serbia The national flag of Serbia is a horizontal tricolour of red, blue, and white with the lesser coat of arms placed left of center. The first recorded use of the Serbian tricolour was in 1835. |

| Coat of arms |  |

Coat of arms of Serbia The national coat of arms of Serbia was adopted in 2004 and is based on the original used during the Kingdom of Serbia (1882-1918). |

| National anthem | Bože pravde The national anthem of Serbia "Bože pravde" (God of Justice) was first used by the Kingdom of Serbia (1882-1918). It was readopted in 2006 as the official anthem of Serbia. | |

Other symbols

| Type | Image | Symbol |

|---|---|---|

| National colours |  |

The national colours of Serbia are red, blue and white,[1][2][3] the Flag of Serbia being commonly called trobojka (the tricolour).[4] This flag was adopted in 1835.[5] |

| National symbol |  |

The Serbian cross is based on the tetragramme, a Byzantine symbol, and is believed to have been adopted at least by the 14th century. It consists of a Greek cross, and four firesteels pointing outwards. It is alleged that the firesteels are acronyms for Only Unity Saves the Serbs. |

| Heraldic symbol |  |

The Serbian eagle, a double-headed white eagle, is depicted on both the coat of arms and flag of Serbia. The heraldic symbol has a long history in Serbian heraldry. The double-headed eagle and the Serbian cross are the main heraldic symbols which represent the national identity of the Serbian people across the centuries.[6] It originated from the medieval Nemanjić dynasty.[6][7] |

| National regalia |  |

The Karađorđević Crown Jewels were created in 1904 for the coronation of King Peter I. The pieces were made from materials that included bronze taken from the cannon Karađorđe used during the First Serbian Uprising. This gesture was symbolic because 1904 was the 100th anniversary of that uprising. The regalia was made in Paris by the famous Falise brothers jewellery company and is currently the only Serbian crown kept in the territory of the Republic of Serbia.[8] |

| Patron saint |  |

Saint Sava, also known as Rastko Nemanjić, is the founder and first Archbishop of the Serbian Orthodox Church (1219–1233). He is the patron saint of Serbia, and education in the country. He is the son of Stefan Nemanja, founder of the Nemanjić dynasty. He is a patron saint in Republika Srpska, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. He also has the honorific title of Father of the Fatherland[9] |

| Folk costume(s) |  |

The most common folk costume of Serbia is that of Šumadija, a region in central Serbia.[10] It includes the national hat, the šajkača,[11][12] and the traditional leather footwear, opanci.[13] Older villagers still wear their traditional costumes.[10] |

| Cultural practice |  |

Slava, veneration of the family's patron saint. Inscribed on UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists. |

| National animal(s) |  |

The gray wolf is greatly linked to Balkan and Serbian mythology and cults.[14] It has an important part in Serbian mythology.[15] In the Slavic, old Serbian religion and mythology, the wolf was used as a totem. In the Serbian epic poetry, the wolf is a symbol of fearlessness.[16] Vuk Karadžić, 19th-century Serbian philologist and ethnographer, explained the traditional, apotropaic use of the name Vuk ("wolf"): a woman who had lost several babies in succession, would name her newborn son Vuk, because it was believed that the witches, who "ate" the babies, were afraid to attack the wolves.[17] Today, the wolf is also depicted on several Serbian municipality coat of arms as a heraldry symbol. |

.jpg.webp) |

The wild boar is greatly linked to ancient Balkan and Serbian culture. The Triballi were an ancient tribe whose name was used as an exonym for the Serbs by archaizing Eastern Roman authors in the Middle Ages.[18] The Triballian boar[19] was part of the historical coat of arms attributed to medieval Serbia by various armorials, Serbia under the Habsburgs, Serbia during First and Second Serbian Uprising against the Ottomans,[20][21] and is depicted on several contemporary Serbian municipality coat of arms in Šumadija. | |

| National bird(s) |  |

The eastern imperial eagle is the national bird of Serbia. It inspired the modern double-headed Serbian eagle heraldry.[22][7] |

|

The griffon vulture is the national bird of Serbia. It inspired the medieval double-headed Serbian eagle heraldry.[23][7] | |

| National tree |  |

The oak (most commonly the pedunculate oak) is a symbol of Serbia,[24] having been part of the historical coat of arms of the Socialist Republic of Serbia, the historical coat of arms and flags of the Principality of Serbia, as well as the current traditional coat of arms and flag of Vojvodina.[25] On the coat of arms, the oak branch at one side symbolized strength and longevity, while the olive branch at the other symbolized peace and fertility.[24] On the socialist coat of arms, the golden oak branch was present next to a golden wreath of wheat. At troublesome times, when there were no churches, people prayed under oak trees where they would carve a cross, zapis; some of these oaks are over 600 years old and are considered sacred.[26] The oak is used in the Serbian Christmas tradition of Badnjak. |

| National flower(s) |  |

The Natalie's ramonda flower is considered a symbol of the Serbian Army's struggle during World War I,[27] with the Serbian forces suffering the largest casualty rate. To commemorate their victims, people in Serbia wear Natalie's ramonda as a symbol of remembrance, especially during Armistice Day, which is a statutory holiday in Serbia since 2012.[28] The plant was scientifically described in 1884 from specimens growing around Niš, by Sava Petrović and Josif Pančić, who named it after Queen Natalija Obrenović. |

|

The Serbian ramonda flower, also known as the phoenix flower due to its ability to be revived when watered, even when fully dehydrated,[29] is considered a symbol of Serbian Army's struggle during World War I, as well as symbolizing the resurrection of the Serbian state after the devastating war. It is used alongside Natalie's ramonda flower, which it shares similarities with, to commemorate the Serbian victims of World War I, especially during Armistice Day, which is a statutory holiday in Serbia since 2012.[30] | |

| National fruit |  |

Plum and its products are of great importance to Serbs and part of numerous customs.[31] A saying goes that the best place to build a house is where a plum tree grows best.[31] The fertile region of Šumadija in central Serbia is particularly known for its plums and šljivovica.[32] |

| National drink |  |

Šljivovica ("plum brandy") is the national drink of Serbia. The name slivovitz is derived from the Serbian language.[33] Plum and its products are of great importance to Serbs and part of numerous customs.[34] A Serbian meal usually starts or ends with plum products.[34] Šljivovica is served as an appertif.[34] A saying goes that the best place to build a house is where a plum tree grows best.[34] Traditionally, šljivovica (commonly referred to as "rakija") is connected to Serbian culture as a drink used at all important rites of passage (birth, baptism, military service, marriage,[34] death, etc.). It is used in the Serbian Orthodox patron saint celebration, slava.[34] It is used in numerous folk remedies, and is given certain degree of respect above all other alcoholic drinks. The fertile region of Šumadija in central Serbia is particularly known for its plums and šljivovica.[35] Serbia is the largest exporter of slivovitz in the world, and second largest plum producer in the world.[36][37] It has a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO). |

| National dishes | .jpg.webp) |

Among national dishes are ćevapčići, pljeskavica and gibanica (see Serbian cuisine) |

| National personification | .jpg.webp) |

Mother Serbia is the female personification of the nation and the metaphoric mother of all Serbs.[38] Serbian national myths and poems constantly invoke Mother Serbia.[39] Most notable depictions of Mother Serbia were sculpted by Đorđe Jovanović, such as those in Belgrade and Kruševac. Her depiction can be seen on the Serbian identity card. |

| Father(s) of the Nation |  |

Stefan Nemanja Vukanović, also known as Saint Simeon the Myrrh-streaming was the Grand Prince of the Serbian Grand Principality (also known as Raška) from 1166 to 1196. A member of the Vukanović dynasty, Nemanja founded the Nemanjić dynasty (one of the most prominent medieval Serbian dynasties), and is remembered for his contributions to Serbian culture and history, founding what would evolve into the Serbian Empire, as well as the national church with his son, Rastko Nemanjić. |

|

Đorđe Petrović, better known by the sobriquet Karađorđe, is a Serbian revolutionary who led the struggle for his country's independence from the Ottoman Empire during the First Serbian Uprising (1804–1813). He is the founder of the Karađorđević dynasty. He also has the honorific title of Father of the Nation.[40] | |

|

Miloš Obrenović, also known as Miloš the Great, is a Serbian revolutionary who led the struggle for his country's independence from the Ottoman Empire during the Second Serbian Uprising (1815–1817). He is the founder of the Obrenović dynasty. He also has the honorific title of Father of the Nation.[41] | |

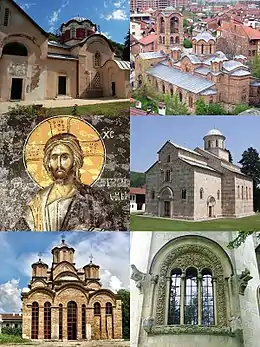

| National monument(s) |  |

Serbia has four cultural monuments inscribed in the list of UNESCO World Heritage: the early medieval capital Stari Ras and the 13th-century monastery Sopoćani; the 12th-century Studenica monastery; the Roman complex of Gamzigrad–Felix Romuliana; and finally the endangered Medieval Monuments in Kosovo (comprising the monasteries of Visoki Dečani, Our Lady of Ljeviš, Gračanica and Patriarchal Monastery of Peć). There are two literary monuments on UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme: the 12th-century Miroslav Gospel, and scientist Nikola Tesla's valuable archive. |

|

The Church of Saint Sava is one of the largest Orthodox churches in the world. The church is dedicated to Saint Sava. It is built on the Vračar plateau, on the location where his remains were burned in 1595 by the Ottoman Empire's Sinan Pasha. From its location, it dominates Belgrade's cityscape, and is perhaps the most monumental building in the city. The design of the church was inspired by Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. | |

| National art |  |

The White Angel, fresco painted by an unknown author in the Mileševa monastery c. 1235 in Serbia, during the reign of King Stephen Vladislav I of Serbia.[42][43] Considered one of the most beautiful works of Serbian and European art from the High Middle Ages, this fresco is considered to be one of the great achievements in European painting.[43] |

|

The Proclamation of Dušan's Law Codex is the name given to each of seven versions of a composition painted by Paja Jovanović c. 1900, which depict Dušan the Mighty introducing Serbia's earliest surviving law codex to his subjects in Skopje in 1349. | |

|

The Kosovo Maiden, painted by Realist Uroš Predić in 1919, is the central figure in a Serbian epic poem by the same name. The painting depicts the aftermath of the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 between Serbia and the Ottoman Empire. | |

|

The Migration of the Serbs is a set of four similar oil paintings made by Paja Jovanović between 1896 and 1945. It depict the Serbs, led by Archbishop Arsenije III, fleeing Old Serbia during the Great Serb Migration of 1690–91. | |

|

The Great People's Assembly of Serbs, Bunjevci and other Slavs in Banat, Bačka and Baranja, painted by Anastas Bocarić c. 1922 or c. 1923. The painting showcases the People's Assembly held in Novi Sad on November 25, 1918, where it was proclaimed the joining of Banat, Bačka and Baranja regions to the Kingdom of Serbia, which would subsequently be incorporated into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, and later into the Republic of Serbia in the form of Vojvodina. | |

| National instrument |  |

The gusle, the national instrument of Serbia,[44][45] accompanied the Serb bards, called guslari, when they sang epic poetry about medieval Serbia and a better future during the Ottoman period and during war-time.[46] |

| National poetry |  |

Serbian epic poetry is the national poetry, traditionally transmitted orally by the national bards (guslari, "gusle players"). Vuk Stefanović Karadžić (1787–1864), the father of the study of Serbian folklore and a major reformer of the Serbian language, collected and wrote down epic poems of the Serbs in the early 19th century.[47] |

| Folk dance |  |

Serbian circle dancing, kolo, includes many varieties (see Serbian dances). The most popular is Užičko kolo.[48] Other popular dances include Moravac, Kokonješte, Žikino kolo and Vranjanka.[49] |

| Handicraft |  |

The Pirot carpet (kilim) is a GI-protected product from southeastern Serbia. |

| Script | The Cyrillic script is an important symbol of Serbian identity.[50] Under the Constitution of Serbia of 2006, Cyrillic is the only script in official use.[51] Serbian Cyrillic is in official use in Serbia, Montenegro and Republic of Srpska.[52] | |

| Salute |  |

The Three-finger salute is commonly used when expressing Serbian Orthodoxy. |

| National hat |  |

The šajkača is the Serbian national hat. A popular national symbol in Serbia since the beginning of the early 20th century, it is typically black, grey or green in colour and is usually made of soft, homemade cloth.

It became widely worn by Serb men during the First Serbian Uprising and was a key component in the uniform of the Serbian military from the beginning of the 19th century until the end of the 20th century. Today, it is mostly worn by elderly men in rural communities. |

| Motto | Само слога Србина спасава |

The phrase "Only Unity Saves the Serbs" (Serbian: Само слога Србина спасава / Samo sloga Srbina spasava) is often said to be displayed on the Serbian cross on the Serbian national coat of arms, in the form of four C-shaped firesteels (sr. "ocila"), which form an acronym of the four Cyrillic letters for "S" (written like Latin "C"). |

| Popular music |  |

Balkan brass.[53] |

References

- The Journal of the Orders & Medals Research Society of Great Britain. Orders and Medals Research Society. 1969. p. 207.

- Chronicles. Rockford Institute. 1994. p. 39.

- Nigel Thomas; Krunoslav Mikulan (2006). The Yugoslav Wars (2): Bosnia, Kosovo and Macedonia 1992 - 2001. Osprey Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-84176-964-6.

- Vojni muzej Jugoslovenske marodne armije (1974). Vesnik. Vol. 19–20.

Srpska trobojka: crveno-plavo-belo

- Зорица Јанковић (2008). Цару на диван: сусрети српских владара и турских султана. "Београд. ISBN 9788675191049.

ферманом је одређена: црвено-плаво-бела тробојка, са водоравно поређаним бојама.

- Atlagić 2009, p. 180.

- "Grb Srbije – šta znači dvoglavi beli orao i kako je nastao novi srpski grb". bastabalkana.com (in Serbian). 13 August 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- Lazarević, Veselin. "(NE)SAČUVANA SRPSKA BAŠTINA". Vratiti srpske krune (in Serbian). Dan online. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- Branko Pešić (1988). Spomen hram Sv. Save na Vračaru u Beogradu: 1895–1988. Sveti arhijerejski sinod Srpske pravoslavne crkve.

Отац Отаџбине Св. Сава је надахнуо Немањи- ну државу идеалима хришћанског патриотизма и створио слободну цркву у слободној држави. Држа- ва је Отечество – земља мојих ота- ца. Држава не сме да буде импери- ја, јер где ...

- Dragoljub Zamurović; Ilja Slani; Madge Phillips-Tomašević (2002). Serbia: life and customs. ULUPUDS. p. 194. ISBN 9788682893059.

- Deliso, Christopher (2009). Culture and Customs of Serbia and Montenegro. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-313-34436-7.

- Resić, Sanimir; Plewa, Barbara Törnquist (2002). The Balkans in Focus: Cultural Boundaries in Europe. Lund, Sweden: Nordic Academic Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-91-89116-38-2.

- Mirjana Prošić-Dvornić (1989). Narodna nošnja Šumadije. Kulturno-Prosvjetni Sabor Hrvatske. p. 62. ISBN 9788680825526.

- Marjanović, Vesna (2005). Maske, maskiranje i rituali u Srbiji. Чигоја штампа. p. 257. ISBN 9788675585572.

Вук као митска животиња дубо- ко је везан за балканску и српску митологију и култове. Заправо, то је животиња која је била распрострањена у јужнословенским крајевима и која је представљала сталну опасност како за стоку ...

- Brankovo kolo za zabavu, pouku i književnost. 1910. p. 221.

Тако стоји и еа осталим атрибутима деспота Вука. Позната је ствар, да и вук (животиња) има зпатну улогу у митологији…У старој српској ре- лигији и митологији вук је био табуирана и тотемска животиња.

- Miklosich, Franz (1860). "Die Bildung der slavischen Personennamen" (Document) (in German). Vienna: Aus der kaiserlich-königlichen Hoff- und Staatdruckerei. pp. 44–45.

- Karadžić, Vuk Stefanović (1852). Српски рјечник (Document) (in Serbian). Vienna: Typis congregationis mechitaristicae. p. 78.

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 9.

- Danko Popović; Dinko Davidov (2004). Studije o srpskoj umetnosti XVIII veka. Српска књижевна задруга. p. 18. ISBN 9788637908685.

- Vanja Kraut; Miodrag Đorđević; Rade Rančić (1985). Istorija srpske grafike od XV do XX veka. Narodni muzej. p. 73. ISBN 9788636700013.

- SANU (1957). Posebna izdanja. SANU. p. 130.

- James Minahan (23 December 2009). The Complete Guide to National Symbols and Emblems [2 Volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 525–. ISBN 978-0-313-34497-8.

- "Opstanak Zasticenih Vrsta" (in Serbian). Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- Elisabeth Hackspiel-Mikosch; Stefan Haas (2006). Civilian uniforms as symbolic communication: sartorial representation, imagination, and consumption in Europe (18th - 21st century). Franz Steiner Verlag. p. 196. ISBN 978-3-515-08858-9.

The oak, symbol of Serbia, symbolized strength, longevity, and the olive branch represented peace and fertility

- "Покрајинска скупштинска одлука о изгледу и коришћењу симбола и традиционалних симбола Аутономне покрајине Војводине". Službeni liist AP Vojvodine (in Serbian) (51). 15 September 2016.

- Andrea Pieroni; Cassandra L. Quave (14 November 2014). Ethnobotany and Biocultural Diversities in the Balkans: Perspectives on Sustainable Rural Development and Reconciliation. Springer. pp. 240–. ISBN 978-1-4939-1492-0.

- President honors Serbian WW1 soldiers in Greece: In commemoration of Armistice Day, President Tomislav Nikolić paid homage to fallen Serbian soldiers at the Greek island of Vido.

- "Serbia to mark Armistice Day as state holiday". 9 November 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- Yuki Nakamura and Yonghua Li-Beisson (Editors)ISBN 9783319259772, Springer, p. 185, at Google Books

- Blečić, Petar (11 December 2015). "Kap vode ih vraća u život". Blic.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Stephen Mennell (2005). Culinary Cultures of Europe: Identity, Diversity and Dialogue. Council of Europe. p. 383. ISBN 9789287157447.

- Grolier Incorporated (2000). The encyclopedia Americana. Grolier. p. 715. ISBN 9780717201334.

- Haraksimová, Erna; Rita Mokrá; Dagmar Smrčinová (2006). "slivovica". Anglicko-slovenský a slovensko-anglický slovník. Praha: Ottovo nakladatelství. p. 775. ISBN 978-80-7360-457-8.

- Mennell 2005, p. 383

- Grolier Incorporated 2000, p. 715

- "FAOSTAT". faostat.fao.org.

- "Razvojna agencija Srbije" (PDF). www.siepa.gov.rs.

- Dubravka Žarkov; Kristen Ghodsee (13 August 2007). The Body of War: Media, Ethnicity, and Gender in the Break-up of Yugoslavia. Duke University Press. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-0-8223-9018-3.

- Renata Salecl (31 January 2002). The Spoils of Freedom: Psychoanalysis, Feminism and Ideology After the Fall of Socialism. Routledge. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-1-134-90612-3.

- Durde Jelenić (1923). Nova Srbija i Jugoslavija, 1788–1921. p. 56.

ОТАЦ ОТАЏБИНЕ – КАРАЂОРЂЕ ПЕТРОВИЋ

- Milivoj J. Malenić (1901). Posle četrdeset godina: u spomen proslave četrdesetogodišnjice Sv. Andrejske velike narodne skupštine. U Drž. štamp. Kralj. Srbije.

да се на престо српски поврати њен ослободилац и оснивалац: Отац Отаџбине, Милош Обреновић Велики,

- "White Angel – the Mileševa monastery". Via Balkans Travel Portal. 22 December 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- "Manastir Mileševa - crkva Belog anđela" [Mileševa Monastery - the Church if the White Angel] (in Serbian). Večernje novosti. 5 August 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- Joel Martin Halpern (1967). A Serbian village. Harper & Row.

Although the wandering guslari no longer exist, the gusle is considered the national instrument of Serbia, and many village men know how to play it. Almost without exception, all villagers can recite parts of the ballads and children learn them ...

- Linda A. Bennett; David Levinson (1992). Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Europe (central, western, and southeastern Europe). G.K. Hall. ISBN 978-0-8161-1811-3.

As for the Serbs, the Montenegrin national instrument is the gusle — a single-horsehair wooden instrument stroked with a horsehair bow. The most important function of the instrument is to provide accompaniment for the singing of oral ...

- Charles Jelavich (1963). The Balkans in Transition: Essays on the Development of Balkan Life and Politics Since the Eighteenth Century. University of California Press. pp. 107–. GGKEY:E0AY24KPR0E.

Sung by bards to the accompaniment of the gusle, the epics reminded the Serbs of their medieval states and promised them a better future. The clergy, hajduks, craftsmen, and ordinary men sang to the gusle. At home, at church gatherings, ...

- Guerber, H. a (2003) [1916]. Book of the Epic. p. 489. ISBN 9780766159020.

This fund of national poetry, transmitted orally by the Serbian guslari or national bards through five centuries of subjection to the Turk, was collected and written down at the beginning of the nineteenth century by

- Ursula Hemetek; Adelaida Reyes; Institut für Volksmusikforschung und Ethnomusikologie--Wien (2007). Cultural diversity in the urban area: explorations in urban ethnomusicology. Institut für Volksmusikforschung und Ethnomusikologie. ISBN 978-3-902153-03-6.

They played newly composed folk music as well as kolos such as Uzicko kolo, a very popular dance melody from Serbia. The dance, one of the musical ethnic symbols of Serbia; might allude to Serbian ethnicity; otherwise we did not find any ...

- Savez udruženja folklorista Jugoslavije. Kongres (1965). Rad ... Kongresa Saveza folklorista Jugoslavije. Savez folklorista Jugoslavie.

Za poslednjih dvadesetak godina Moravac je potisnuo svoje prethodnike Kokonjeste, 2ikino kolo i Vranjanku (brzu), naravno, ne potpuno, ali ipak toliko efikasno da je zauzeo mesto pored njih, pa i ispred njih.

- Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. BRILL. 13 June 2013. pp. 414–. ISBN 978-90-04-25076-5.

- Article 10 of the Constitution of the Republic of Serbia (English version Archived 2011-03-14 at the Wayback Machine)

- Ronelle Alexander (15 August 2006). Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, a Grammar: With Sociolinguistic Commentary. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-299-21193-6.

- Carol Silverman (24 May 2012). Romani Routes: Cultural Politics and Balkan Music in Diaspora. Oxford University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-19-530094-9.

The brass band has become a Serbian national symbol, and bands such as Boban Markovic are popular on the world music circuit.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Symbols of Serbia.

- "Symbols of Statehood" (PDF).

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.