Navajo medicine

Navajo medicine covers a range of traditional healing practices of the Indigenous American Navajo people. It dates back thousands of years as many Navajo people have relied on traditional medicinal practices as their primary source of healing. However, modern day residents within the Navajo Nation have incorporated contemporary medicine into their society with the establishment of Western hospitals and clinics on the reservation over the last century.

| Part of a series on |

| Medical and psychological anthropology |

|---|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

In addition, medicine and healing are deeply tied with religious and spiritual beliefs, taking on a form of shamanism. These cultural ideologies deem overall health to be ingrained in supernatural forces that relate to universal balance and harmony. The spiritual significance has allowed the Navajo healing practices and Western medical procedure to coexist as the former is set apart as a way of age-long tradition.

Health and traditional belief

Illness

Illness is described as the manifested mental or physical consequence brought on by a disruption of patient harmony. Some causes of this disruption include taboo transgression, excessive behavior, improper animal contact, improper ceremony conduction, or contact with malignant entities including spirits, skin-walkers and witches. Breaking taboos is believed to be acting against the principles devised by the Holy People that withhold personal harmony with the environment. There are some cases in which illness is merely the result of accident. Personal injury or illness can be the error from lack of judgment or unintentional contact with harmful creatures of nature. Illness can also be brought on by malevolent practitioners of negative medicine. This belief in hóchxǫ́, translated as "chaos" or "sickness", is the opposite of hózhǫ́ and helps to explain why people, who are intended to be in harmony, perform actions counter to their ideals, thus reinforcing the need for healing practices as means of balance and restoration. Those who practice witchcraft include shape shifters who intend to use spiritual power and ceremony to acquire wealth, seduce lovers, harm enemies and rivals. Ill health is also believed to be brought upon by chindi (ghost) who can bring about a kind of ghost sickness that leads others to death.[1]

Occupational roles

Medicine men

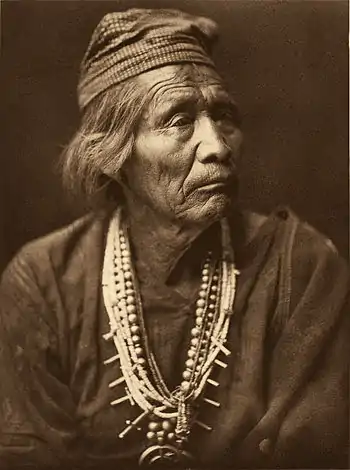

Navajo Hatááłii are traditional medicine men who are called upon to perform healing ceremonies. Each medicine man begins training as an apprentice to an older practicing singer. During apprenticeship, the apprentice assembles medicine bundles (jish) required to perform ceremonies and assist the teacher until deemed ready for independent practice. Throughout his lifetime, a medicine man can only learn a few chants as each requires a great deal of time and effort to learn and perfect. Songs are orally passed down in traditional Navajo from generation to generation. Unlike other American Indian medical practitioners that rely on visions and personal powers, a healer acts as a facilitator that transfers power from the Holy People to the patient to restore balance and harmony. Healing practice is performed within a ceremonial hogan. It is common for medicine men to receive payment for their healing services. In the past, healing was exchanged for sheep. In modern times however, monetary payment has become a widely accepted form of compensation. Women can also play the role of healer in medicinal practice.[1]

Hand tremblers

Hand tremblers act as medical diagnosticians and are sometimes called upon in order to verify an illness by drawing on divine power within themselves as received from the Gila monster. Typical services can be provided in the form of songs, prayers, and herb usage. During a diagnosis a hand trembler traces symbols in the dirt while holding a "trembling arm" over the patient. Movement of the arm signifies a new drawn symbol or a possible identification to the cause of illness. Once a solution has been found, the patient can be referred to a herbalist or singer needed to perform a healing ceremony.[1]

Mechanisms of traditional healing

Ceremonies

A number of healing ceremonies are performed according to a given patient situation. Some chants and rites for curing purposes include:

- The Blessing Way rite is usually done over pregnant women or any person for promoting good health and prosperity. The ceremony is the most frequently used one and resembles how the Holy People acted to create the world and establish harmony.

- The Enemy Way rite is done as an exorcism to remove ghosts, violence and negativity that can bring disease and do harm to host health and balance.

- The Night Way is a healing ceremony that takes course over nine days. Each day the patient is cleansed through a varying number of exercises done to attract holiness or repel evil in the form of exorcisms, sweat baths, and sand painting ceremonies. On the final day the one who is sung over inhales the "breath of dawn" and is deemed cured.[2]

Herbs

See Navajo ethnobotany for a list of plants and how they were used.

Navajo Indians utilize approximately 450 species for medicinal purposes, the most plant species of any native tribe. Herbs for healing ceremonies are collected by a medicine man accompanied by an apprentice. Patients can also collect these plants for treatment of minor illnesses. Once all necessary wild plants are collected, an herbal tea is made for the patient, accompanied by a short prayer. In some ceremonies, the herbal mixture causes patient vomiting to ensure bodily cleanliness. Purging can also require the patient to immerse themselves in a yucca root sud bath. Any distribution of medicinal herbs to a patient is accompanied by spiritual chanting.

The Navajo people recognize the need for botanical conservation when gathering desired healing herbs. When a medicinal plant is taken, the neighboring plants of the same species receive a prayer in respect. Despite this fact, the collection of medicinal herbs has been more difficult in recent years as the result of migrating plant spores.

Popular plants included in Navajo herbal medicine include Sagebrush (Artemisia spp.), Wild Buckwheats (Eriogonum spp.), Puccoon (Lithospermum multiflorum), Cedar Bark (Cedrus deodara), Sage (Salvia spp.), Indian Paintbrush (Castilleja spp.), Juniper Ash (Juniperus spp.), and Larkspur (Delphinium spp.).[3]

Sand paintings

Sand painting is the transfer of strength and beauty to the patient through various drawings made by a medicine man in the surrounding sand during a ceremony. Elaborate figures are drawn in the sand using colorful crushed minerals and plants. Many sand paintings contain depictions of spiritual yeii to whom a medicine man will ask to come into the painting in order for patient healing to occur. After each ceremony, the sacred sand painting is destroyed.[1]

U.S. government influence during the 20th century

External aid and reliance

As prompted by the Meriam Report in 1928, federal commitment to Indian health care under the New Deal increased as the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) Medical Division expanded, making medical care more accessible, affordable, and tolerated by the Navajo populace.

Increased demand of BIA medical care by Native Indians conflicted with post World War II conservatives who resented government funded and privileged health care. Growing interest in Indian termination policy in addition to unaided medical attention called for a transition of medical affluence by both native and non-native parties.

Under the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, funding was provided for the United States Public Health Service to gain a "Division of Indian Health" which would help provide a stronger federal commitment to health care. This division would later be renamed the division of Indian Health Service. Despite its initial successes, the Indian Health Service on the Navajo Nation faced challenges of being underfunded and understaffed. In addition, language barriers and cross-cultural tensions continued to complicate the hospital and clinic experience.[1]

Preserving tradition and promoting identity

Expanding Western medical influence and diminishing medicine men in the second half of the 20th century helped to initiate activism for traditional medical preservation as well as Indian representation in Western medical institutions.

With the coming of the 1970s spawned new opportunities for Navajo medical self-determination. The Indian Health Care Improvement Act 1976 aided local Navajo communities in autonomously administering their own medical facilities and prompted natives to gain more bureaucratic positions in the Indian Health Service. The gained presence of native people in medical institutions also helped ease many who regarded non-Navajo medical providers with mistrust.[4]

Community medical care that relied less on government involvement also took root in Rough Rock and Ganado, both towns that administered their own health care services. Navajo Nation Health Foundations was run in Ganado solely by Navajo people. In expressing identity in the medical community, the Navajo Nation took advantage of the National Health Planning and Resources Development Act to create the Navajo Health Systems Agency in 1975, being the only American Indian group to do so during that time.[1]

References

- Davies, Wade. Healing Ways, Navajo Health Care In The Twentieth Century. Univ of New Mexico Press, 2001.

- "Navajo Ceremonials". www.hanksville.org. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- Roebuck, Paul. "Navajo Ethnobotany - Diné Nanise and Ethnobotanical Analysis of Early Navajo Site LA 55979." . N.p., 2007. Web. 16 Dec 2011. [drarchaeology.com/publications/earlynavajoethnobot.pdf]

- Schwarz, Maureen Trudelle. I Choose Life: Contemporary Medical and Religious Practices in the Navajo World. Univ of Oklahoma Pr, 2008