Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij

The Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij ((Netherlands Steamboat Co)), abbreviated as NSM or NSBM, was a Dutch shipping line focused on inland navigation. In the 1820s it was important for the quick introduction of steam power on the Dutch rivers and on the Rhine. NSM owned the major shipbuilding company Fijenoord.

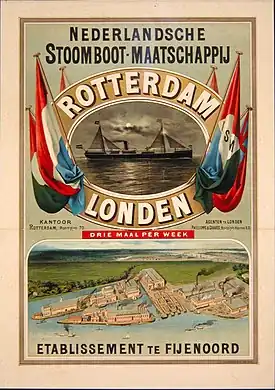

Poster of the Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij with its shipyard Fijenoord. | |

| Industry | Shipping line, ship building |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | Van Vollenhoven, Duthil en Co. (1822) |

| Founded | 1823 |

| Headquarters | , |

Key people | Gerhard Moritz Roentgen, Jean Chrétien Baud |

Early years

G.M. Roentgen

%252C_RP-P-OB-88.080.jpg.webp)

Gerhard Moritz Roentgen (1795-1852) was a Dutch navy officer born in Esens, Lower Saxony. He was trained at the naval academy of Enkhuizen. In 1816 he left for the Dutch East Indies on board the ship of the line Brabant. He did not get further than Portsmouth, where Brabant was docked, and then sent back to the Netherlands. While there, he got orders to gather information about English warship construction. In June 1818 Roentgen and the engineers C. Soetermeer and C.J. Glavimans got orders to make a more formal research trip to England. Here Roentgen became fascinated by the development of steam propulsion.[1]

Foundation of the lines from Rotterdam to Antwerp, Veere and Nijmegen

Van Vollenhoven, Dutilh en Co. was a company established to create a shipping line between Moerdijk and the Dordtsche Kil.[1] The permit for the firm's activity was obtained by the widow Balguerie, born Dutilh. On 20 January 1823 the steamboat De Nederlander was laid down by W. & J. Hoogendijk in Capelle aan den IJssel. She was launched on 12 April 1823.[2][3] De Nederlander was the first Dutch steam vessel, even though her 40 hp engines were made by Maudslay, At the time, the plan was to establish a line between Rotterdam and Antwerp.[4] Antwerp was the best harbor of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands (1815-1830).

On 3 June 1823 De Nederlander was to make her first trip from Rotterdam to Antwerpen via Dordrecht, Willemstad, Ooltgensplaat, Zijpe (Bruinisse), Wemeldinge, Gorishoek (Tholen) and Bath.[5] This trip was cancelled, but on 18 June King William went from Vlissingen to Antwerpen on board De Nederlander. In September 1823 De Nederlander also started to frequent Veere and Nijmegen.

On 16 November 1823 De Nederlander made a 'pleasure cruise' to Gorcum. The last trip of the season was planned on 21 November 1823. The plan was to restart the line to Antwerpen in 1823 with three boats. The location of the boat and the office would be moved to the street De Boompjes Number 140.[6] The pleasure cruise was obviously successful, because it was followed by a cruise to Zaltbommel on 23 November, and one to Gouda and one to Brielle on 30 November. The final trip of the year went to 's-Hertogenbosch on 9 December.

Foundation of the NSM (1824)

.jpg.webp)

On 10 November 1823 Van Vollenhoven, Dutilh & Comp. got royal permission to found a Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij. The founders would take 290 shares for 145,000 guilders. Together, the founders (Jean Chrétien Baud, C. van Vollenhoven, and G.M. Roentgen) would have to remain in possession of at least a quarter of the shares.[7] The corporation charter shows the hand of King William. E.g. article 5 forced the company to use only vessels and engines made in the Netherlands.[8]

On 15 December 1823 M.A. Dutilh, Widow C. Balguerie, Cornelis Balguerie, and C.C. Dutilh declared that they had retired from Van Vollenhoven, Duthilh en Co. They would get their share in the association back via two short term loans.[9]

The Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij (NSM) was founded on 1 March 1824. C. van Vollenhoven became the financial executive administrerende directeur. G.M. Roentgen became the executive for materiel and the engineer of the company directeur van het materieel en werktuigkundige. The supervisory board was made up of: C. De Jong van Rodenburgh; Jonkheer A.C. Twent; mr. J.K. Sontag; J.C. Baud; John Cockerill; and J.A. van Vollenhoven. Van Vollenhove, Dutilh & Co. was dissolved at the same time.[10]

The presence of John Cockerill in the supervisory board was no coincidence. One of King William's many projects to re-establish the economy of the Netherlands, was the establishment of a solid coal and iron industry near Liège. He achieved this by successfully investigating why British iron was so much better than continental iron, and by taking part in John Cockerill & Cie, which built a large plant near Seraing. John Cockerill & Cie would build the engines for the next NSM boats based on those of De Nederlander.

Expansion of shipping lines

On 10 May 1824 the shipyard of W. & J. Hoogendijk in Capelle aan de IJssel launched De Zeeuw of 50 hp. At that moment this shipyard had three more boats under construction for NSM, which all had to be finished in 1824. With these, regular lines from Rotterdam to Antwerp, Zeeland (i.e. Veere), and Nijmegen were to be established.[11] The plan was that De Stad Antwerpen and De Nederlander would serve the line to Antwerp. De Stad Nijmegen would be on the Rotterdam - Nijmegen line. De Zeeuw would be on the line to Zeeland, and constitute the reserve.[12]

In 1824 De Nederlander continued to alternate between Antwerp, Veere and Nijmegen.[13] In August 1824 De Zeeuw started an almost daily schedule to Antwerp, while De Nederlander continued to serve all three cities. It seems that De stad Antwerpen and De stad Nijmegen were not finished in 1824.

In 1825 the third and fourth boat of the plan were finished. In March 1825 De stad Antwerpen was mentioned.[14] In May 1825 De stad Nijmegen was in action near Hellevoetsluis.[15] The line to Antwerp was the busiest, by July 1825 it had become a daily service. The boats from Rotterdam to Veere held a biweekly or even sparser schedule. A line from Veere over Vlissingen, Terneuzen and Hansweert ended at Bath, where it connected to the Rotterdam - Antwerp line.[16]

It is interesting that the original design of De Stad Nijmegen called for an iron hull vlak with wooden planking. This would have made it a very early composite ship. Problems with the delivery of iron sheets prevented this plan, as well as the construction of a completely iron steamer (De Keulenaar?) that same year.[17]

NSM also had a weekly line from Rotterdam to Arnhem over the Lek and Nederrijn. This became a regular connection on 5 August 1826.[18] It had a coach service from Rotterdam to Gouda, connecting to the boats.[19]

Atlas: biggest steamship of the world

In 1824 the Dutch government ordered NSM to build a steamship which could reach the Dutch East Indies without having to call at any port along the way. Atlas was laid down by Hoogendijk on 8 January 1825.[20] Length was to be 71 m, beam 5.5 m and displacement 1,200 ton.[21]

After a lot of delays, Atlas made her first unsatisfactory trials on fresh water in August 1828.[21] At the time she was the biggest steamship of the world. In August 1829 dry rot was found in her hull, and it was 18 July 1830 when she finally left for sea. However, the machines consumed so much coal, that it was deemed unwise to send her to the Dutch East Indies.[22] The probably cause was that the ship was not rigid enough, making that propulsion axis could not turn freely.[23]

Expanding the capital

In May 1825 the NSM offered extra shares to the public in order to execute further plans. These were: [24]

- A steamboat for the Rhine

- A steamship (packet) for a line between Amsterdam and Hamburg (The Batavier)

- A tugboat for service on the rivers and close to sea (Hercules?)

- A steamboat for a service between Antwerp and Boom

Rotterdam - Cologne line

On 26 October 1824 De Zeeuw had steamed to Cologne in order to reconnoiter the Rhine up to that place for the iron Keulenaar of 100 hp, which was under construction. On 29 October she arrived in Cologne under huge public attention.[25][26] On 11 November 1824 De Zeeuw was back in Rotterdam. In spite of the failure of the projected boat, NSM had a line between Rotterdam, Nijmegen, Düsseldorf and Cologne operational in July 1825.[16] NSM and Johann Friedrich Cotta perhaps understood the possibilities and limits of what was possible on the Rhine. In cooperation NSM and two new German shipping lines made agreements to cooperate, and divide the Rhine in three sections.[27]

In 1825 the Dampfschiffahrtsgesellschaft von Rhein und Main (DGRM) was founded in Mainz. It was headed by merchants from Mainz, Frankfurt, and Strasbourg. It aimed to establish shipping lines between these cities, and as far up the Main as feasible.[28] It ordered the steamboat Concordia at NSM.

On 3 October 1825 the Preußisch-Rheinische Dampfschiffahrt-Gesellschaft (PRDG) was founded by merchants from Cologne, headed by Peter Heinrich Merkens. It ordered the steamer Friedrich Wilhelm at NSM, which was identical to Concordia. When the draft of Concordia proved too deep to operate above Mainz, DGRM offered the PRDG to use her in a partnership. PRDG then used both boats between Cologne and Mainz. The relations between NSM and PRDG were good, because PRDG limited itself to the section between Köln and Mainz.[29] In 1832 the D.G. von Rhein und Main was merged into the PRDG.

On 31 August 1825 the steamboat De Rijn was ready for service on this NSM line. The second boat for the Rhine was bought in Antwerp. It was probably James Watt, built by Woods on the Clyde in 1822. In 1826 a new steam engine was built for her, and her name was changed to De Stad Keulen. The engine was finished in August 1828, and she was then used in the service from Antwerp to Cologne.[19]

The Batavier line (to London)

On 9 May 1825 Batavier I was laid down by Fop Smit for an Amsterdam - Hamburg line.[30] When Paul van Vlissingen's Amsterdamsche Stoomboot Maatschappij established an Amsterdam - Hamburg line before the NSM could, NSM offered De Batavier to several parties. In the end NSM used her to open a line from Antwerp to London in September 1829. In April 1830 the line was changed to one from Rotterdam to London.

The Batavier line faced stiff competition from the English shipping lines, with their much deeper pockets. It was also hindered by its single vessel not being available to sail in winter time. This meant that other (all English) lines blocked freight from Rotterdam from using the Batavier line, by threatening the senders with not accepting their cargo in winter time. In spite of all of this, the Batavier line exceeded expectations. At times, Batavier transported more than 100 passengers, and sleeping accommodations were soon extended for 120 persons.[31]

The reason for the unexpected success of the Batavier line was that a single company offered transport from places up the Rhine to London and back. This offer was expanded by cooperation with the first German steam shipping lines on the Rhine.

Steam tug service on the Rhine

In 1830 most shipping on the Rhine was still done by sailboats. Apart from loading cargo on a steam vessel, there was another steam powered alternative for the unreliable upstream voyage of these sailboats. This was to tow the sailboats upstream, and then let them find their own way back downstream. Already in 1825, NSM started to tug sailboats up the Rhine. That same year, the government offered a loan of 200,000 guilders to NSM to build a tugboat. This became Hercules, she was the world's first vessel with a compound steam engine, made from the re-used the machines of Agrippina.[32]

In 1829 NSM started to operate Hercules and Stad Keulen on the Rhine. The first idea had been that Hercules would tow the engine-less Agrippina upstream, but this proved unfeasible. Some changes were then made to Hercules, so she could carry cargo herself, and tow 4-6 sailboats upstream to Emmerich am Rhein or even Düsseldorf.[33] From Emmerich the freighter / tugs continued alone towards Cologne, while the sailboats were pulled against the strong currents by horses.[34] During the Belgian Revolution (1830-1832) many of NSM's boats were hired by the government.

Orestes and Pylades

In 1823 the Dutch East Indies governor general Godert van der Capellen asked for two steamships to combat piracy. In 1826 NSM got the order to build Orestes and Pylades. They would each have two 80 hp engines by Cockerill, and a three mast Barque sail plan.[35] On 5 September 1827 Orestes was launched by Cornelis Smit. She had a flat bottom, and shifting keel.[36] Construction problems led to the state ordering the demolishment of the ships in August 1831. Both ships were then sold to NSM without the engines.[37] Orestes was broken up by NSM.

In November 1832 NSM offered to equip Pylades as a warship, using the engines of Atlas. When the government accepted the offer, a lot of problems surfaced. Pylades had been left in the open, and many parts had been scavenged, leading to leakage. The same applied to the engines of Atlas.[38] After many delays and expenses Pylades steamed to Batavia on 2 January 1835. After only 30 minutes, she showed leakage, and she sank shortly after midnight. In the end NSM got 60% from the insurers.[39]

The foundation of Fijenoord

NSM's own repair shop

When NSM was founded in 1824 there was no steam engine manufacturing and repair infrastructure near Rotterdam. NSM therefore could not do without its own repair shop. In November 1824 the Badhuis at the Boompjes in Rotterdam was bought to establish a smithy. In May 1825 the shipyard of H. Blanken in Oost IJsselmonde was bought. Here NSM erected a shear leg, crucial for lifting boilers.[40] In Oost-IJsselmonde NSM built Stad Frankfort[19] and probably Stad Arnhem. In October 1825 NSM then started negotiations to rent the terrain at Fijenoord from the municipality of Rotterdam.[40]

The foundation of Fijenoord

Repairing ships or building ships is something else then building steam engines. It is generally assumed that the foundation of NSM's own machine factory and shipyard Fijenoord came about by a conflict with NSM's partner John Cockerill. While the machines of NSM's second and later boats were built by John Cockerill & Cie based on those of De Nederlander, they were also built according to designs and specifications by Roentgen. With the risk involved, NSM of course feared that once she had proven the possibilities of steam propulsion, others would start competing services based on NSM's knowledge. Cockerill and NSM had therefore agreed that NSM would only order at Cockerill, and Cockerill would only deliver to NSM. For a time, the agreement prevented a lot of competition, but in the end, the state did not like this quasi monopoly. It agreed to buy half of the shares of Cockerill's machine factory in Seraing, if he would end his contract with NSM.[41] In 1827 NSM then founded the Etablissement (shipyard) Fijenoord.

In Business as a shipping line (1830-1859)

Shipping on the Rhine

.JPG.webp)

As stated above, NSM, PRDG and DGRM had created a comfortable quasi-monopoly for steam shipping on the Rhine. Apart from the beneficial (for NSM) limitation that any shipping line needing government permission to operate, there were other limitations. It was e.g. not allowed to ship cargo to Cologne in Dutch barges. Each vessel needed a permit, and on the Prussian section of the Rhine 60 guilders had to be paid in taxes for every trip.[32]

All this changed on 17 July 1831, when all limitations on shipping on the Rhine were cancelled. By 1834 shipping on the Rhine had become the most important activity of the NSM. At the time NSM had 11 vessels with totalling 1,000 hp and a capacity of 380 last. At that time, relations with the PRDG were very good. The companies had agreed about their interests in shipping on the Rhine, and representatives of PRDG were regularly present at NSM shareholder meetings.[32]

In 1836 the Dampfschiffahrts-Gesellschaft für den Nieder- und Mittelrhein (DGNM) was founded in Düsseldorf. The General Steam Navigation Company was its main shareholder. In 1837 a Dutch-Prussian trade agreement gave their subjects' vessels equal rights.[32] In September 1838 DGNM started a line from Rotterdam to Mainz.[42] This had 5 steamboats in 1838, while the PRDG went up to Strasbourg with 11 boats.[29] This led to very strong competition. The worst consequence was that all parties now began to try to service a stretch from Rotterdam to high up the Rhine. NSM opened a line to Mainz with 3 boats in July 1840.

Financial (mis)management

NSM started with a share capital of 336,500 guilders. By 1827 this was 750,000 guilders, over which a dividend of 9.5% was paid. Meanwhile NSM borrowed a lot of money. In 1828 divided was 8%, but NSM failed to repay on certain loans. In 1829 NSM had to borrow another 150,000 guilders, and decided on separate accounting for NSM and its shipyard at Fijenoord. In 1832 the failure to acquire a loan of 40,000 guilders to finish Agrippina showed how serious the situation was. That year her shares were traded at 35% in Amsterdam. NSM herself bought these to create a fire insurance fund. In 1836 a financial plan was made. Share capital was increased by 375,000 guilders, and this was used to repay debts. Dividend would be limited till the financial situation had become more stable.[43]

In 1839 NSM's shares were traded slightly above 100% for the first time in its history, but this was probably due to fraud. In March 1841, a banker in Cologne got in trouble. It was then discovered that NSM's executive Cs. van Vollenhoven had loaned money at this banker without knowledge of NSM's supervisory board. NSM's shareholders then had to lend 300,000 guilders to prevent a crisis. An extraordinary shareholders meeting on 29 April 1841 then fired Van Vollenhoven, and reformed NSM. It also started a thorough examination of the accounts of NSM. It was found that Van Vollenhoven had been at least 'very careless'.[44]

An October 1841 valuation of the assets of the company found that these appeared in the books for a much higher value than was realistic. The former King William I agreed to help NSM with a loan of 600,000 guilders at 5%, and was allowed to appoint a commissioner. The new management started a program to economize.[45] While NSM's debt totaled 1,973,000 guilders in 1844, this had been brought down to 1,146,000 on 31 December 1847.[46]

Tug service on the Rhine

In 1832 the government tug service for the Waal was founded. It stretched from Rotterdam to Lobith.[47] The tug service was executed by NSM.[48] In 1833 the service was only profitable for NSM because Hercules had a fuel-efficient compound engine.[49] Tugboats used in the service were Hercules, Stad Arnhem and Stad Keulen.[50] In 1834 NSM built Simson.[32] In 1836 NSM made a contract with the Ministry for National Industry (Departement voor de Nationale Nijverheid) about towage upstream of Lobith. The provided loan for construction an iron tugboat led to the construction of the tugboat De Rhijn of 400 hp. For a time, the high price of British coal made that the tugs were fired with peat.[32] The tug service on the Rhine provided a very long term steady income to NSM. the government often subsidizing it by over 100,000 guilders a year. In 1841 the service upstream of Lobith was cancelled.

The contract between the state and NSM was to end in 1848. It was nevertheless renewed in June 1849.[51] The reasoning behind this was that the tug service led to less maintenance on the many towpaths along the Lek. The contract for the government steam tug service on the Waal finally ended on 1 January 1858.[52]

Introduces barge towage on the Rhine

The fundamental problem with towing sailing barges upstream was that it was only economical for the sailing barges when they faced adverse winds. It meant that the tugboats could not operate with profit at other times. The steam lines on the Rhine then got the idea to build dumb barges from sheet iron. It would spell the end of the sailing barge on the Rhine.[53]

In 1841 NSM introduced the towage of iron barges on the Rhine. The first barge was 180 by 24 feet, with a depth of hold of 11 feet. Loaded with 4,880 hundredweight, it had a draft of 3.75 feet.[54] In 1842 the competing PRDG founded the Kölner Dampfschleppschifffahrts Gesellschaft.[55] In Mainz the Mainzer Schleppdampfschiffahrts-Verein was founded.

NSM's barge towage came in strong competition with the Kölner Dampfschleppschifffahrts Gesellschaft and the company from Mainz.[56] In 1845 the Kölner Dampfschleppschifffahrts Gesellschaft (KDG) had 4 tugboats, 28 barges and a sea going ship.[56]

Nevertheless, on the Lower Rhine barge towage was not that dominant in the beginning. By 1866 roughly 11% of the upstream goods at Lobith would arrive by steamboat. The towed barges would account for 27%, and towed sailboats for 53%. Another 10% would be carried by sailboats which went upstream under sail, or had been towed by people or horses.[57]

The Rotterdam - Antwerpen line

On 19 June 1839 NSM reopened its line to Antwerp.[42] In June 1846 the competing Reederij Amicitia got her first steamboat. It was an iron boat called Amicitia, built by L. Smit en Zoon with engines by Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel.[58] Already in December 1847, NSM agreed to end her service to Antwerp and transfer it to Amicitia.[59] In return NSM would receive 20,000 guilders a year from Smit & Veder for 10 years.[60]

Trouble on the Rhine

By 1849, NSM was in big trouble on the Rhine. The austerity program, and the repayment of loans had caused that its ships had not been properly maintained, and that some boats had not been replaced in time.[61] By 1849 NSM had De Nederlander II, Ludwig, Antwerpen, No. 22, Willem II, Prins de Joinville, No. 23, and as reserve No. 24 serving this line. De Nederlander, Ludwig, Antwerpen, and No. 24 were made of wood. For cargo it had Stad Dussseldorp, the tug Rijn I, and the iron Rhine-barges Rijn III en Rijn IV.[62]

After making many repairs to its boats, NSM was able to offer a daily service to Mannheim in 1850. However, only De Nederlander, Prins de Joinville, No. 22 and No. 23 were able to more or less regularly sail according to schedule, the others were often hours off. This drove passengers away, and meant that NSM could not ask the same passenger fares that the competition got.[63] Furthermore, De Nederlander, Ludwig, and No. 24 had really too much draft to operate on the Manheim line. The year was definitely ruined when big repairs on Ludwig and Antwerpen forced NSM to use the very inefficient and uncomfortable No. 24 during the summer.[64]

In September 1850 the manager of NSM declared that with the boats he had at his disposal, it would not possible to make a profit on the Rhine.[64] He furthermore noted that the troubles of the company were very much due to constantly repairing old vessels that could not sail profitably. If NSM's activity on the Rhine was to survive, it had to build two new boats of the type of No. 22, but with 6 inch less draft. This would cost 220,000 guilders.[65]

In 1851 a new Agrippina was laid down. She was to receive the machines of Ludwig. De Rhijn would be demolished and two tugs: Rotterdam I and Rotterdam II would be constructed from its material. In 1852 the steamboat Stolzenfels was laid down. Shipping on the Rhine now became rather profitable again, and so the shallow draft steamboats Nederlander and Rijnlander were ordered for a fast line between Cologne and Mainz. In 1855 a new Batavier came into service on the Rotterdam - London line.[66]

The end of NSM's shipping lines on the Rhine

The 1853 partnership between PRDG and DGNM, which later became the Köln-Düsseldorfer was a setback for NSM. By using ever more efficient boats, and offering ever more departures, the partnership got to dominate the market for passenger traffic on the Rhine.[67]

In 1857 NSM ranked third of the Rhine shipping lines with regard to mixed passenger / cargo boats, having 11 boats. In barge towage however, NSM was far behind the competition. In 1857 KDG had 4 tugboats with 32 barges, DGNM had 4 tugboats with 12 barges, and 5 other companies had about a dozen or more towed barges. NSM had 5 tugboats and only 5 barges.[68]

In 1857 losses on the Rhine were 77,000 guilders, and negotiations were started to merge with the German firms.

NSM as a shipbuilding company with a small shipping line (1859-1895)

Sale of the main shipping activities

On 3 December 1858 NSM received an offer by J.D. Dijkmans to buy NSM's activities on the Rhine. On 31 January 1859 an extraordinary meeting of shareholders mandated the supervisory board to sell the Rhine shipping activities. The buyer was a new company called Nederlandsche Stoomboot Reederij (NSR). The price was 250,000 guilders of NSM shares, 20,000 guilders of NSR shares, and bonds for 730,000 at 3%, to be paid back in 20 years. Transfer of the assets took place on 15 March 1859.[52] De Nederlandsche Stoomboot Rederij (modern spelling) considered itself to be the successor to NSM.[27]

NSM is primarily a shipyard

The deal with the Nederlandsche Stoomboot Reederij meant that NSM's only remaining shipping activity was the Batavier line. The shipbuilding activities had now definitely become more important than the shipping activities. In May 1867 D.L. Wolfson, chief executive of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Grofsmederij became chief executive of NSM. Wolfson tried to expand the Batavier line, but he was also the first chief executive that was regularly at Fijenoord, instead of only residing at De Boompjes.[69]

But continues to be a shipping line

While NSM's shipyard had thus become far more important than its shipping activities, it still had the ability to organize shipping. In 1874 it entered into the tender for providing shipping lines in the Dutch East Indies for 15 years. The reason for NSM to participate in the tender, was that if the (British!) Nederlands Indische Stoomvaart Maatschappij (NISM) won the tender, almost all of the required ships would be built in England. In spite of the very small difference in offers, the Dutch government awarded the tender to the foreign NISM.[70]

NSM builds an ocean liner

As owner of Fijenoord, NSM was very much interested in building ocean liners. However, by the late 1870s a vicious circle prevented the Dutch ship building industry from entering this market. Dutch shipping lines did not order ocean-going steamships in the Netherlands, because Dutch shipyards had no experience in building these vessels. In turn the lack of experience was of course due to the lack of orders. In fact it was a bit more complicated than this. In the late 1860s the Dutch navy had ordered (the engines for) sea-going ironclads and monitors from the Dutch shipbuilding industry. These were in fact copies of ships built in Great Britain, but during trials the ships were much slower and far-less fuel-efficient than the foreign originals.[71] During the 1870s Dutch engineers, amongst them B.J. Tideman, succeeded in catching up with the British, but by then the lack of experience was problematic.

Now, the character of the NSM as a big shipbuilder with a small shipping line came to the rescue. In 1880 the shareholders agreed to build an ocean liner for shipping to the Dutch East Indies. The expectation was that some shipping line would buy it during construction. This did not happen, and when Nederland was ready in 1881, she was used to set up an NSM line to Baltimore. This line failed and led to serious losses. However, Nederland served its purpose. In 1881 and 1882 three ocean liners were ordered at Fijenoord.[70]

Hollandse Stoomboot Maatschappij

When the Batavier line to London gave good results, NSM founded the Hollandse Stoomboot Maatschappij together with the Hollandsche IJzeren Spoorweg-Maatschappij in January 1885.

End of the shipping activities

By 1895 the Batavier Line was the only shipping activity left with NSM. The Batavier line and the name Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij itself was sold to W.H. Müller & Co in 1895. NSM then changed its name to Maatschappij voor Scheeps- & Werktuigbouw Fijenoord.[72]

Ships built by or for Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij

For ships built at NSM's own shipyard at Feijenoord, see Fijenoord.

| Ship | Type | Launched[73] | Size in ton[73] | Shipyard | Engines | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Nederlander | Steamboat | March 1823 | 150 | W. & J. Hoogendijk | Maudslay | First ship of NSM |

| De Zeeuw | Steamboat | June 1824 | 156 | W. & J. Hoogendijk | Cockerill | First ship designed by NSM |

| Stad Antwerpen | Steamboat | June 1824 | 160 | W. & J. Hoogendijk | Cockerill | |

| De Rijn | Steamboat | August 1825 | 218 | W. & J. Hoogendijk | Cockerill | 1829: Prinz Friedrich von Preußen, 1831 Prins Frederik |

| Friedrich Wilhelm | Steamboat | April 1826 | 240 | ? Smit, Alblasserdam | Seaward | Second German steamboat on the Rhine |

| Concordia | Steamboat | July 1826 | 240 | ? Smit, Alblasserdam | Seaward | First German steamboat on the Rhine |

| Agrippina | Steamboat | March 1827 | 300 | ? Smit, Alblasserdam | Taylor & Martineau | Later lengthened |

| Hercules | Steam paddle tugboat | June 1827 | 300 | Boom | Billard, Jemappes (first) | Second engine was a compound steam engine. |

| SS De Batavier | Paddle Steamship | August 1827 | 600 | L. Smit en Zoon | Cockerill | |

| Stadt Frankfurt | Steamboat | August 1827 | 130 | NSM IJsselmonde | Seaward | Later compounded in Ruhrort |

References

- De Boer, M.G. (1923), Leven en bedrijf van Gerhard Moritz Roentgen

- De Boer, M.G. (1939), 100 jaar Nederlandsche Scheepvaart

- Van Dijk, A. (1998), "Geschikt tot verblijf en voortbrenging van de koninklijke familie, het stoomjacht Leeuw", Rotterdams Jaarboekje, pp. 314–327

- Eckert, Christian (1900), "Rheinschiffahrt im XIX. Jahrhundert", Staats- und sozialwissenschaftliche Forschungen, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig

- "Iets over stoom-vaartuigen", De Nederlandsche Hermes, tijdschrift voor koophandel, zeevaart en, M. Westerman, Amsterdam, no. 8, pp. 53–63, 1828

- Lintsen, H.W. (1993), Geschiedenis van de techniek in Nederland. De wording van een moderne samenleving 1800-1890. Deel IV

- Löhnis, Th. P. (1916), "De Maatschappij voor scheeps- en werktuigbouw Fijenoord te Rotterdam, voorheen de Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij", Tijdschrift voor economische geographie, pp. 133–156

- Nieuwenhuis, Gt. (1840), Aanhangsel op het algemeen woordenboek van kunsten en wetenschappen, vol. VII, p. 408

- NSM (1823), Statuten van de Nederlandsche stoomboot-maatschappij, opterigten te Rotterdam

- NSM (1850), Verslag van den direkteur der Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij aan de Algemene Vergadering

- Rahusen, I.J. (1867), "Nederlands handel en scheepvaart op den Rijn in 1866", Staatkundig en staathuishoudkundig jaarboekje voor 1867, De vereniging voor de statistiek in Nederland, pp. 164–188

- Treue, Wilhelm (1984), Wirtschafts- und Technikgeschichte Preußens, ISBN 9783110853179

- Van der Vlis, D. (1970), "Het Stoomschip "Pylades", 1826-1835", Mededelingen van de vereniging voor Zeegeschiedenis, pp. 17–22

Notes

- Lintsen 1993, p. 74.

- "Nederlanden". 's Gravenhaagsche courant. 16 April 1823.

- Nieuwenhuis 1840, p. 408.

- "Nederlanden". Groninger courant. 18 April 1823.

- "Stoomboot de Nederlander". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 3 June 1823.

- "Stoomboot de Nederlander". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 13 November 1823.

- "Oprigting eener Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij te Rotterdam". Rotterdamsche courant. 23 December 1823.

- NSM 1823, p. 2.

- "Advertisements". Rotterdamsche courant. 30 December 1823.

- "De Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 4 March 1824.

- "Advertisements". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 15 May 1824.

- De Boer 1923, p. 50.

- "Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij". Arnhemsche courant. 21 February 1824.

- "Rotterdam den 7 Maart". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 10 March 1825.

- "Hellevoetsluis, den 31 Mei". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 3 June 1825.

- "Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 23 July 1825.

- Van Dijk 1998, p. 326.

- "Arnhem, den 7. Augustus". Arnhemsche courant. 8 August 1826.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 137.

- "Nederlanden". 's Gravenhaagsche courant. 12 January 1824.

- "Nederlandsche Marine, proefneming met het stoomschip Atlas". Arnhemsche courant. 18 November 1828.

- De Boer 1939, p. 80.

- Lintsen 1993, p. 78.

- "Deelneming in de Nederlandsche Stoomboot-Maatschappij". Utrechtsche courant. 25 April 1825.

- "Nijmegen, den 2. November". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 5 November 1824.

- "Preußen". Kölnische Zeitung. 30 October 1824.

- "De Nederl. Stoombootreederij". Scheepvaart. 24 February 1913.

- "Duitschland". Leydse courant. 16 September 1825.

- Treue 1984, p. 426.

- "Rotterdam, den 10 Mei". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 13 May 1825.

- De Boer 1939, p. 157.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 139.

- Eckert 1900, p. 253.

- "Aan de redactie". Algemeen Handelsblad. 24 March 1830.

- Van der Vlis 1970, p. 17.

- "Rotterdam den 7 september". Rotterdamsche courant. 8 September 1827.

- Van der Vlis 1970, p. 18.

- Van der Vlis 1970, p. 19.

- Van der Vlis 1970, p. 21.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 136.

- De Boer 1939, p. 81.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 140.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 141.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 142.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 143.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 145.

- "Mengelwerk". Arnhemsche courant. 22 March 1834.

- "Tweede kamer der Staten-Generaal". Nederlandsche staatscourant. 29 December 1840.

- "IJzeren Spoorweg". Algemeen Handelsblad. 29 August 1834.

- "Amsterdam, Dingsdag 15 October". Algemeen Handelsblad. 16 October 1833.

- NSM 1850, p. 3.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 148.

- Eckert 1900, p. 255.

- Eckert 1900, p. 256.

- "Keulen, 11 Nov". Algemeen Handelsblad. 24 November 1842.

- Eckert 1900, p. 257.

- Rahusen 1867, p. 170.

- "Rotterdam, 18 Junij". N.R.C. 19 June 1846.

- "Binnenland". Algemeen Handelsblad. 9 December 1847.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 144.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 146.

- NSM 1850, p. 6.

- NSM 1850, p. 13.

- NSM 1850, p. 9.

- NSM 1850, p. 14.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 147.

- Eckert 1900, p. 279.

- Eckert 1900, p. 284.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 150.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 152.

- Lintsen 1993, p. 94.

- Löhnis 1916, p. 155.

- Hermes 1828, p. 58-61.