Nemegtosaurus

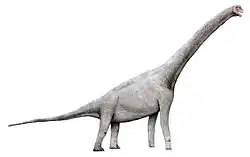

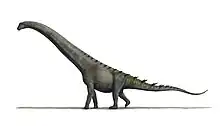

Nemegtosaurus (meaning 'Reptile from the Nemegt') was a sauropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Period of what is now Mongolia. It was named after the Nemegt Basin in the Gobi Desert, where the remains — a single skull — were found. The skull resembles diplodocoids in being long and low, with pencil-shaped teeth. However, recent work has shown that Nemegtosaurus is in fact a titanosaur, closely related to animals such as Saltasaurus,[1] Alamosaurus and Rapetosaurus.

| Nemegtosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

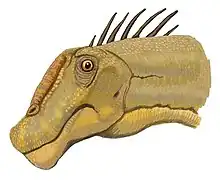

| Cast of the skull of Nemegtosaurus on a reconstructed Opisthocoelicaudia skeleton, Museum of Evolution of Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Clade: | †Titanosauria |

| Clade: | †Lithostrotia |

| Family: | †Nemegtosauridae |

| Genus: | †Nemegtosaurus Nowinski, 1971 |

| Species | |

| |

Discovery and taxonomy

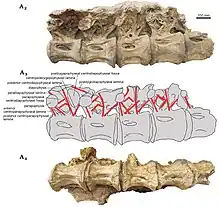

The skull of Nemegtosaurus comes from the same beds as the titanosaur Opisthocoelicaudia, which is known from a skeleton lacking the neck and skull. Originally, the referral of Nemegtosaurus to Diplodocoidea and Opisthocoelicaudia to Camarasauridae argued that the two represented different species. Both of these genera represent advanced titanosaurians, however, raising the possibility that the two are in fact the same animal.[1] Relocation of the Nemegtosaurus type locality in Central Sayr and discovery of postcrania comparable to those Opisthocoelicauda holotype at the Nemegtosaurus holotype locality has discussed the possibility that Opisthocoelicauda is a junior synonym. Consequently, Opisthocoelicaudiinae would be a junior synonym of Nemegtosauridae.[2] In 2019, Alexander O. Averianov and Alexey V. Lopatin in a paper describing new specimens of Nemegtosaurus reanalyzed the argument for synonymy and determined that the taxa were not synonymous because shared characters between the species were either difficult to determine or based on comparisons with a specimen which actually belonged to Nemegtosaurus.[3]

The type species, Nemegtosaurus mongoliensis, was first described by Nowinski in 1971 on the basis of ZPAL MgD-I/9. A second species, N. pachi, was described by Dong in 1977 on the basis of the teeth IVPP V.4879, recovered from the Subashi Formation, but is a nomen dubium.

Classification

The cladogram below follows Franca et al. (2016):[4]

| Lithostrotia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description

Like other titanosaurs, the teeth are slender pencil-like structures that are ground down at a sharp angle to produce a chisel-like tip. The diet of Nemegtosaurus is unknown, however. There are no plant fossils from the Gobi, but during the Late Cretaceous, flowering plants became increasingly diverse, although in many environments ferns and conifers were still more common. Neither is it clear whether Nemegtosaurus browsed high in the trees or grazed on low-growing plants; related titanosaurs include both long-necked browsing forms like Rapetosaurus and short-necked forms like Bonitasaura.

Comparisons between the scleral rings of Nemegtosaurus and modern birds and reptiles suggest that it may have been cathemeral, active throughout the day at short intervals.[5]

Paleoenvironment

Nemegtosaurus is found in the Maastrichtian aged (66-72 Ma) Nemegt Formation, which makes it one of the last sauropods on earth. There, on a lush river delta flowing through the ancient sands of the Gobi Desert, Nemegtosaurus would have coexisted with animals like the ornithomimid Gallimimus, the alvarezsaurid Mononykus, the velociraptorine Adasaurus, and the giant, saber-clawed therizinosaur Therizinosaurus. It also lived alongside the tyrannosaur Tarbosaurus. With its possible body length of 12 metres (39 ft),[6] an adult Nemegtosaurus may been able to defend against Tarbosaurus, but juveniles would have been vulnerable.

References

- Benton, Michael J. (2012). Prehistoric Life. Edinburgh, Scotland: Dorling Kindersley. pp. 332–333. ISBN 978-0-7566-9910-9.

- Currie, P.J.; Wilson, J.A.; Fanti, F.; Mainabayar, B.; Tsogtbaatar, K. (3 November 2017). "Rediscovery of the type localities of the Late Cretaceous Mongolian sauropods Nemegtosaurus mongoliensis and Opisthocoelicaudia skarzynskii: Stratigraphic and taxonomic implications". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 494: 5–13. Bibcode:2018PPP...494....5C. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.10.035. hdl:11585/622592 – via ResearchGate.

- Averianov, Alexander; Lopatin, Alexey (2019). "A possible new specimen of the Late Cretaceous Mongolian sauropod Nemegtosaurus and sauropod diversity in the Nemegt Formation". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 64. doi:10.4202/app.00596.2019.

- França, M.A.G.; Marsola, J.C.d A.; Riff, D.; Hsiou, A.S.; Langer, M.C. (2016). "New lower jaw and teeth referred to Maxakalisaurus topai (Titanosauria: Aeolosaurini) and their implications for the phylogeny of titanosaurid sauropods". PeerJ. 4: e2054. doi:10.7717/peerj.2054. PMC 4906671. PMID 27330853.

- Schmitz, L.; Motani, R. (2011). "Nocturnality in dinosaurs inferred from scleral ring and orbit morphology". Science. 332 (6030): 705–708. Bibcode:2011Sci...332..705S. doi:10.1126/science.1200043. PMID 21493820. S2CID 33253407.

- Holtz, T. R.; Rey, L. V. (2007). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. Random House. ISBN 9780375824197.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) Genus List for Holtz 2012 Weight Information

- Nowinski, A. (1971). Nemegtosaurus mongoliensis n. gen., n. sp. (Sauropoda) from the uppermost Cretaceous of Mongolia. Palaeontologia Polonica 25: 57–81.

- Wilson, J. (2005). Redescription of the Mongolian sauropod Nemegtosaurus mongoliensis Nowinski (Dinosauria: Saurischia) and comments on Late Cretaceous sauropod diversity. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 3. 283 - 318. 10.1017/S1477201905001628.