Nevado de Longaví

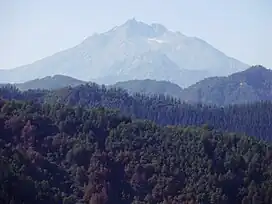

Nevado de Longaví is a volcano in the Andes of central Chile. The 3,242 m (10,636 ft) high volcano lies in the Linares Province, which is part of the Maule Region. It features a summit crater and several parasitic vents. The volcano is constructed principally from lava flows. Two collapses of the edifice have carved collapse scars into the volcano, one on the eastern slope known as Lomas Limpias and another on the southwestern slope known as Los Bueye. The volcano features a glacier and the Achibueno and Blanco rivers originate on the mountain.

| Nevado de Longaví | |

|---|---|

Photo of Nevado de Longaví from the cordillera of Linares | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 3,242 m (10,636 ft)[1] |

| Listing | List of volcanoes in Chile |

| Coordinates | 36.193°S 71.161°W[1] |

| Geography | |

Nevado de Longaví | |

| Parent range | Andes |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Last eruption | 4890 BCE ± 75 years[1] |

The oldest volcanic activity occurred one million years ago. After a first phase characterized by the production of basaltic andesite, the bulk of the edifice was constructed by andesitic lava flows. The volcanic rock that makes up Nevado de Longaví features an unusual magma chemistry that resembles adakite (having geochemical characteristics of magma thought to have formed by partial melting of altered basalt that is subducted below volcanic arcs). It may be the consequence of the magma being unusually water-rich, which may occur because the Mocha fracture zone subducts beneath the volcano.

Nevado de Longaví was active during the Holocene. 6,835 ± 65 or 7,500 years before present an explosive eruption deposited pumice more than 20 kilometres (12 mi) away from the volcano. A lava flow was then erupted over the pumice. The last eruption occurred about 5,700 years ago and formed a lava dome. The volcano has no historic eruptions but fumarolic activity is ongoing. Nevado de Longaví is monitored by the National Geology and Mining Service of Chile.

Geography

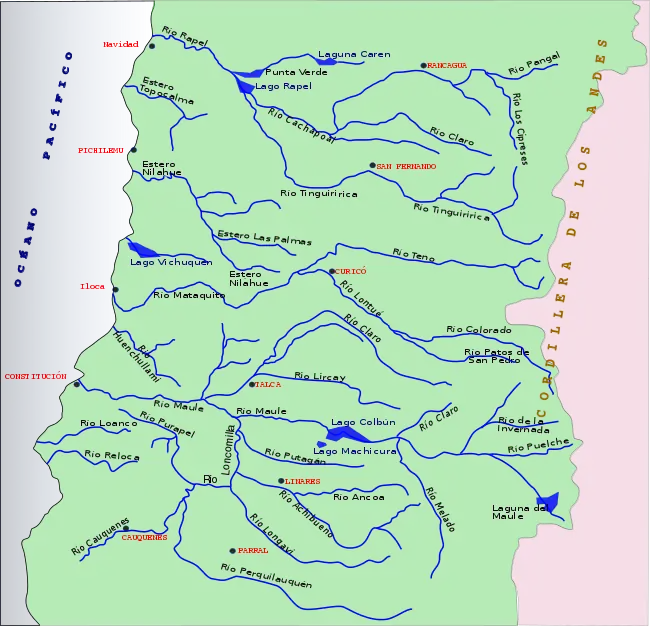

Nevado de Longaví lies in the Longaví commune of Linares Province, Maule Region.[2]

Regional

Nevado de Longaví lies in the Andean Mountain Range's Southern Volcanic Zone, which extends between 33 and 46 degrees southern latitude.[2] It is one among 60 volcanoes in Chile and Argentina that lie within the Southern Volcanic Zone. Among the largest volcanic eruptions in this area were the 1932 Quizapu and the 1991 Cerro Hudson eruptions.[3] Nevado de Longaví is usually put into the "Transitional Southern Volcanic Zone", one of the four segments which the Southern Volcanic Zone is subdivided into; they are characterized by different thicknesses of the crust that the volcanoes are constructed on and by differences in the volcanic rocks.[4] Farther east lie the Tatara-San Pedro and Laguna del Maule volcanoes.[5]

Geology

Volcanism in the Southern Volcanic Zone is caused by the subduction of the Nazca Plate beneath the South American Plate in the Peru–Chile Trench,[6] at a pace of 40 millimetres per year (1.6 in/year).[4] The Southern Volcanic Zone is one among several volcanic belts in the Andean Volcanic Belt. Areas without volcanic activity separate it from the Central Volcanic Zone in the north and the Austral Volcanic Zone in the south. These gaps appear to coincide where the Juan Fernández Ridge and the Chile Rise, respectively, subduct in the Peru–Chile Trench.[7] In the volcanic gaps, the subducting slab seems to be attached to the overriding plate without an asthenosphere in between, suppressing the production of magma.[3]

There is a strong north–south gradient among volcanoes of the Southern Volcanic Zone. The northernmost volcanoes are the highest[7] and lie on thicker crust which causes their magmas to have a stronger crustal contribution.[6] The output of the northernmost volcanoes is dominated by andesitic and more evolved magmas and they have the highest quantity of incompatible elements in their magmas. Southern volcanoes are lower, tend to erupt mafic magmas and are located west of the continental divide.[7]

Volcanism in areas of subduction is caused by the release of slab fluids from the subducting slab into the abovelying asthenospheric mantle. The injection of such fluids triggers fluxing and the formation of magmas. Conversely, the descending slab itself is usually not considered a major contributor to magma genesis. Such exceptional magmas are often referred to as adakites, but magmas with such a chemistry can also originate by other processes.[6]

Local

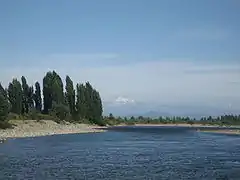

View on Longavi from the Achibueno River at Palmilla, Linares

View on Longavi from the Achibueno River at Palmilla, Linares View on Longavi from Parral, Linares

View on Longavi from Parral, Linares Longavi from route L-75 Parral-Digua

Longavi from route L-75 Parral-Digua An oil painting depicting Longavi from 1859

An oil painting depicting Longavi from 1859

Nevado de Longaví lies within a small mountain chain.[8] It was formerly considered 3,080 m (10,100 ft)[9] or 3,181 m (10,436 ft) high;[10] the accepted elevation is 3,242 metres (10,636 ft).[1] The volcano has a summit crater and many adventive craters on its slopes.[2] The summit crater is heavily degraded by erosion.[11] Lava flows extend radially away from the summit crater and form the bulk of the volcano. The adventive craters are also associated with lava flows.[2] These lava flows are accompanied by breccia and reach thicknesses of 4–15 metres (13–49 ft).[7] Lahar deposits are found on the eastern slopes.[12]

Scarps on the east–southeast flanks resulted from sector collapses of the volcano.[2] This collapse is known as Lomas Limpias and its scar has a surface area of c. 2 square kilometres (0.77 sq mi).[7] The collapse scar was later filled with products from explosive eruptions.[2] Another collapse occurred on the south–southwestern flank, forming the Los Bueyes collapse and terrace deposits.[7]

Nevado de Longaví is a relatively small volcano.[7] With a diameter of 9 kilometres (5.6 mi), a basal surface area of 64 square kilometres (25 sq mi) and a height above base level of 1,800 metres (5,900 ft), Nevado de Longaví has a volume of about 20 cubic kilometres (4.8 cu mi).[2]

The basement beneath the volcano is formed by the volcaniclastic Cura-Mallín Formation of Eocene–Miocene age, Miocene plutons and the lavic-breccia Pliocene-Pleistocene Cola de Zorro formation. This last formation was identified as forming a deeply eroded volcano in the Cordón de Villalobos south of Nevado de Longaví.[7] This volcano 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) south of Nevado de Longaví[13] is known as Villalobos.[6] The emplacement of this formation was facilitated by a decrease in the compressional stress that had affected the region prior to the Pliocene.[14]

Some isolated monogenetic volcanic centres can be found southeast of Nevado de Longaví. Aside from Villalobos, this includes Resago and Loma Blanca. The first and the last are of Pleistocene age,[15] based on their preservation. Resago is post-glacial. The last two centres appear to be related to a geological lineament that flanks the eastern slopes of Nevado de Longaví.[13]

A glacier is found on the southern slope,[12] between 1989 and 2017 glacier cover has decreased by over 95% with less than 0.2 square kilometres (0.077 sq mi) of glacier cover remaining.[16] Previous glaciation is also supported by the presence of glacial striations on lava flows and of lahar deposits.[12] The Rio Blanco originates on the southeastern slope of Nevado de Longaví,[2] within the collapse scar. It turns south and west around the volcano in a fishhook pattern. The Estero Martinez and Quebrada Los Bueyes rivers also originate on Nevado de Longaví, on the western and southern flank respectively. They are both tributaries of the Rio Blanco.[7] The Achibueno River also originates on the eastern flank of Nevado de Longaví in a lake of the same name. It flows first northeastward and then turns around the volcano.[17]

Composition

Nevado de Longaví has chiefly erupted andesite, which forms about 80% of the volcano.[7] Smaller amounts of basalt and dacite were also erupted by the volcano,[2] the former in the early stages of activity and as basaltic andesite inclusions, the latter during the Holocene.[7]

Early stage rocks contain phenocrysts of clinopyroxene, olivine and plagioclase. Mainstage rocks in addition contain amphibole and orthopyroxene.[7] In the Holocene rocks, apatite, iron and titanium oxides and sulfides have been found.[6] Aside from minerals, gabbro and mafic rocks form enclaves. Granite xenoliths are also found. Unlike these granites, the gabbros appear to be cumulates considering their chemical similarity to Nevado de Longaví rocks.[7]

The chemistry of Nevado de Longaví's magmas is unusual among the volcanoes of the South Volcanic Zone.[2] For example, the potassium content is unusually low. Likewise, incompatible elements are underrepresented. Modal amphibole is much more prevalent. Nevado de Longaví's magmas have been referred to as adakitic,[7] the only magmas of such chemistry in the Southern Volcanic Zone,[6] but this classification has been contested.[7] Fractional crystallization of amphibole has been invoked to explain some of the compositional patterns.[7]

On the basis of their rubidium content, Nevado de Longaví's magmas have been classified in two groups. The rubidium-rich group resembles that of other volcanoes in the Southern Volcanic Zone; the rubidium-poor group conversely is the "unusual" one. The differences appear to reflect both different parental magmas and different magma evolution. There is a temporal pattern of the magmas becoming more rubidium-poor over time.[7]

The unusual chemical patterns appear to reflect that the magmas erupted from Nevado de Longaví were extremely rich in water. Such a pattern has also been noted at Mocho-Choshuenco and Calbuco. All these volcanoes are located above the points where fracture zones intersect the Peru–Chile Trench, and it has been proposed that these fracture zones channel water into the mantle.[7] In the case of Nevado de Longaví, the Mocha fracture zone is subducting beneath the volcano.[6]

Eruptive history

Early stage basaltic andesite lava flows crop out on the northern and southwestern slopes of Nevado de Longaví. They originated at a site c. 400 metres (1,300 ft) below the present-day summit and reach thicknesses of 100–150 metres (330–490 ft). Individual flows are about 1–5 metres (3 ft 3 in – 16 ft 5 in) thick.[7] These volcanic rocks are up to one million years old.[6]

During the main growth stage, volcanic activity was approximately constant considering the homogeneous structure of the lava flows. Temporary periods of dormancy however occurred, causing the formation of erosion valleys on the northern slope that were then filled by younger lava flows. These younger lava flows were themselves subject to glaciation.[7]

Holocene

The last activity occurred during the Holocene,[2] and included explosive activity. It was centered in the eastern collapse scar and on the summit region. In the eastern collapse scar, possibly subglacial activity formed a 30 metres (98 ft) thick sequence including clasts, lava flows and silt.[7]

6,835 ± 65[7] or 7,500 years before present,[6] a large explosive eruption occurred. It deposited dacitic pumice more than 20 kilometres (12 mi) southeast from the volcano. Maximum thickness of the deposits is 30 metres (98 ft).[7] It is also known as the Rio Blanco fall deposit.[6] In the eastern collapse scar, the pumice was later buried by an andesitic lava flow,[7] which is undated and carries the name Castillo Andesite.[6]

The last eruption formed a lava dome within the collapse scar and the summit area.[7] This eruption occurred about 5,700 years ago.[6] A secondary collapse of the lava dome formed a 0.12 cubic kilometres (0.029 cu mi) large block and ash flow that descended the eastern slopes[2] and covers a surface area of about 4 square kilometres (1.5 sq mi).[6]

There is no reported historical volcanic activity,[2] but fumarolic activity has been reported[1] and remote sensing has found thermal anomalies on a scale of about 4 K (7.2 °F).[18] The volcano together with Lomas Blancas has been prospected for the potential of obtaining geothermal energy; estimated capacities are 248 megawatts.[19]

Hazards

The volcano is ranked 22 on Chile's national volcano hazard scale.[2] The towns closest to the volcano are Cerro Los Castillos, La Balsa, La Orilla, Las Camelias and Rincón Valdés;[20] renewed eruptions could result in debris flows, eruption columns, lava flows and pyroclastic flows on the volcano and surrounding valleys.[21] The Mendoza Province in Argentina could also be potentially affected by activity at Nevado de Longaví.[20]

The first recorded ascent occurred in 1965 by S. Kunstmann and W. Foerster, but evidence reported during that ascent implies that humans had reached the mountain earlier.[9] Otherwise, Nevado de Longaví is one of the important tourist attractions of the commune.[22]

References

- "Nevado de Longavi". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- "Volcán Nevado de Longaví" (PDF). SERNAGEOMIN (in Spanish). 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2017.

- Stern, Charles R. (2004-12-01). "Active Andean volcanism: its geologic and tectonic setting". Revista Geológica de Chile. 31 (2): 161–206. doi:10.4067/S0716-02082004000200001. ISSN 0716-0208.

- Salas et al. 2017, p.1108

- Salas et al. 2017, p.1109

- Rodriguez, C.; Selles, D.; Dungan, M.; Langmuir, C.; Leeman, W. (2007-11-01). "Adakitic Dacites Formed by Intracrustal Crystal Fractionation of Water-rich Parent Magmas at Nevado de Longavi Volcano (36.2 S; Andean Southern Volcanic Zone, Central Chile)". Journal of Petrology. 48 (11): 2033–2061. doi:10.1093/petrology/egm049. ISSN 0022-3530.

- Sellés, Daniel; Rodríguez, A. Carolina; Dungan, Michael A.; Naranjo, José A.; Gardeweg, Moyra (2004-12-01). "Geochemistry of Nevado de Longaví Volcano (36.2°S): a compositionally atypical arc volcano in the Southern Volcanic Zone of the Andes". Revista Geológica de Chile. 31 (2): 293–315. doi:10.4067/S0716-02082004000200008. ISSN 0716-0208.

- Pissis 1875, p.24

- Club, American Alpine (1997-10-31). American Alpine Journal, 1974. The Mountaineers Books. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-930410-71-1.

- Pissis 1875, p.25

- Pissis 1875, p.120

- Déruelle, B. (August 1976). "Les volcan Plio-Quaternaires de la Cordillère des Andes a 36o-37oS, Chili central" (PDF). SERNAGEOMIN (in French). pp. 96–97.

- Salas et al. 2017, p.1113

- Salas et al. 2017, p.1112

- Salas et al. 2017, p.1110

- Reinthaler, Johannes; Paul, Frank; Granados, Hugo Delgado; Rivera, Andrés; Huggel, Christian (2019). "Area changes of glaciers on active volcanoes in Latin America between 1986 and 2015 observed from multi-temporal satellite imagery". Journal of Glaciology. 65 (252): 549. Bibcode:2019JGlac..65..542R. doi:10.1017/jog.2019.30. ISSN 0022-1430.

- Rivera, Jorge Boonen (1902-01-01). Ensayo sobre la geografía militar de Chile (in Spanish). Impr. Cervantes. p. 497.

- Pyle, D. M.; Mather, T. A.; Biggs, J. (2014-01-06). Remote Sensing of Volcanoes and Volcanic Processes: Integrating Observation and Modelling. Geological Society of London. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-86239-362-2.

- Aravena, Diego; Alfredo, Lahsen (2012). "Assessment of Exploitable Geothermal Resources Using Magmatic Heat Transfer Method, Maule Region, Southern Volcanic Zone, Chile" (PDF). GRC Transactions. 36: 132 – via GRC Geothermal Library.

- "Nevado de Longaví". SERNAGEOMIN (in Spanish).

- "Volcán Nevado de Longaví". SERNAGEOMIN (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Turismo y comunas de la provincia". gobernacionlinares.gov.cl (in Spanish).

Bibliography

- Pissis, Pedro José Amadeo (1875-01-01). Geografía física de la república de Chile (in Spanish). Inst. Geogr. de Paris.

- Salas, Pablo A.; Rabbia, Osvaldo M.; Hernández, Laura B.; Ruprecht, Philipp (2017-04-01). "Mafic monogenetic vents at the Descabezado Grande volcanic field (35.5°S–70.8°W): the northernmost evidence of regional primitive volcanism in the Southern Volcanic Zone of Chile". International Journal of Earth Sciences. 106 (3): 1107–1121. Bibcode:2017IJEaS.106.1107S. doi:10.1007/s00531-016-1357-5. ISSN 1437-3254. S2CID 132741731.

Further reading

- Biggar, John (2005). The Andes: A Guide for Climbers (3rd ed.). Andes Publishing (Scotland). p. 304 pp. ISBN 978-0-9536087-2-0.

- González-Ferrán, Oscar (1995). Volcanes de Chile. Santiago, Chile: Instituto Geográfico Militar. p. 640 pp. ISBN 978-956-202-054-1. (in Spanish; also includes volcanoes of Argentina, Bolivia, and Peru)