News from Nowhere

News from Nowhere (1890) is a classic work combining utopian socialism and soft science fiction written by the artist, designer and socialist pioneer William Morris. It was first published in serial form in the Commonweal journal beginning on 11 January 1890.

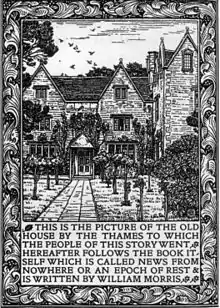

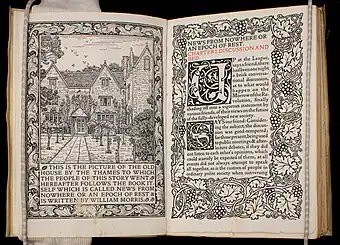

Frontispiece | |

| Author | William Morris |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | NA |

Publication date | 1890 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback, Paperback) |

| Pages | 186 |

In the novel, the narrator, William Guest, falls asleep after returning from a meeting of the Socialist League and awakes to find himself in a future society based on common ownership and democratic control of the means of production. In this society there is no private property, no big cities, no authority, no monetary system, no marriage or divorce, no courts, no prisons, and no class systems. This agrarian society functions simply because the people find pleasure in nature, and therefore they find pleasure in their work.

The novel explores a number of aspects of this society, including its organisation and the relationships which it engenders between people. Morris fuses Marxism and the romance tradition when he presents himself as an enchanted figure in a time and place different from Victorian England. As Morris, the romance character, quests for love and fellowship—and through them for a reborn self—he encounters romance archetypes in Marxist guises. Old Hammond is both the communist educator who teaches Morris the new world and the wise old man of romance. Dick and Clara are good comrades and the married lovers who aid Morris in his wanderings. The journey on the Thames is both a voyage through society transformed by revolution and a quest for happiness. The goal of the quest, met and found though only transiently, is Ellen, the symbol of the reborn age and the bride the alien cannot win. Ellen herself is a multidimensional figure: a working class woman emancipated under socialism, she is also a benign nature spirit as well as the soul in the form of a woman.[1] The book offers Morris' answers to a number of frequent objections to socialism, and underlines his belief that socialism will entail not only the abolition of private property but also of the divisions between art, life, and work.

In the novel, Morris tackles one of the most common criticisms of socialism; the supposed lack of incentive to work in a communist society. Morris' response is that all work should be creative and pleasurable. This differs from the majority of Socialist thinkers, who tend to assume that while work is a necessary evil, a well-planned equal society can reduce the amount of work needed to be done by each worker. News from Nowhere was written as a libertarian socialist response to an earlier book called Looking Backward, a book that epitomises a kind of state socialism that Morris abhorred. It was also meant to directly influence various currents of thought at the time regarding the tactics to bring about socialism.[2]

Looking Backward

Morris reviewed the novel Looking Backward in the Commonweal on 21 June 1889. In his review, Morris objects to Bellamy's portrayal of his imagined society as an authority for what socialists believe. Morris writes, 'In short a machine life is the best which Mr. Bellamy can imagine for us on all sides; it is not to be wondered at then that this, his only idea for making labour tolerable is to decrease the amount of it by means of fresh and ever fresh developments of machinery … I believe that this will always be so, and the multiplication of machinery will just multiply machinery; I believe that the ideal of the future does not point to the lessening of men's energy by the reduction of labour to a minimum, but rather the reduction of pain in labour to a minimum, so small that it will cease to be pain; a dream to humanity which can only be dreamed of till men are even more completely equal than Mr. Bellamy's utopia would allow them to be, but which will most assuredly come about when men are really equal in condition.'[3]

Morris's basic antipathy with Bellamy arose chiefly from his disagreement with Bellamy's social values and aesthetic convictions. While Bellamy favoured the urban, Morris favoured the pastoral; while Bellamy lauded the Industrial Revolution and the power of the machine, Morris yearned for the restoration of an organic way of life which utilised machines only to alleviate the burdens which humans might find irksome; while Bellamy sought salvation through an omnipotent state, Morris wished for a time when it would have withered away.[1]

More specifically, Morris criticised the limited nature of Bellamy's idea of life. He identifies five concerns—work, technology, centralisation, cities, arts—which demonstrates the "half change" advanced in Looking Backward. Morris's review also contains an alternate future society in each of these instances. This was the framework based on which he would later attempt to elaborate his vision of a utopia in News from Nowhere.[4]

Gender roles

In News from Nowhere Morris describes women in the society as ‘respected as a child bearer and rearer of children desired as a woman, loved as a companion, un-anxious for the future of her children’ and hence possessed of an enhanced 'instinct for maternity'. The sexual division of labour remains intact. Women are not exclusively confined to domestic labour, although the range of work they undertake is narrower than that of man; but domestic labour is seen as something for which women are particularly fitted.[5] Moreover, 'The men have no longer any opportunity of tyrannising over the women, or the women over the men; both of those took place in old times. The women do what they can do best and what they like best, and the men are neither jealous nor injured by it.'[6] The practice of women waiting on men at meals is justified on the grounds that, 'It is a great pleasure to a clever woman to manage a house skilfully, and to do so that all house-mates about her look pleased and are grateful to her. And then you know everybody likes to be ordered about by a pretty woman…'[5]

Morris presents us with a society in which women are relatively free from the oppression of men; while domestic work, respected albeit gender-specific in Morris's work here as elsewhere, is portrayed as a source of potential pleasure and edification for all denizens of his Utopia.

Marriage

Morris offers a Marxist view of marriage and divorce. Dick and Clara were once married with two children. Then Clara ‘got it in her head she was in love with someone else,’ so she left Dick only to reconcile with him again.[7] Old Hammond informs the reader that there are no courts in Nowhere, no divorce in Nowhere, and furthermore no contractual marriage in Nowhere. When dealing with marriage and divorce Old Hammond explains, ‘You must understand once for all that we have changed these matters; or rather that our way of looking at them has changed…We do not deceive ourselves, indeed, or believe that we can get rid of all the trouble that besets the sexes… but we are not so mad as to pile up degradation on that unhappiness by engaging in sordid squabbles about livelihood and position, and the power of tyrannising over the children who have been the result of love or lust.'[6] In Nowhere people live in groups of various sizes, as they please, and the nuclear family is not necessary.

Concerning marriage, the people of Nowhere practice monogamy but are free to pursue romantic love because they are not bound by a contractual marriage.

Education

Early in the novel we learn that though the people of Nowhere are learned there is no formal schooling for children. Although Oxford still exists as a place to study the 'Art of Knowledge', we learn that people are free to choose their own form of education. As for educating children, we learn that children in Nowhere ‘often make up parties, and come to play in the woods for weeks together in the summer time, living in tents, as you see. We rather encourage them to do it; they learn to do things for themselves, and get to know the wild creatures; and you see the less they stew inside houses the better for them.’[6]

Here Morris breaks away from the traditional institutions of 19th century England. Learning through nature is the best suited lifestyle for this agrarian society.

"How We Might Live"

News from Nowhere is a utopian representation of Morris’ vision of an ideal society. "Nowhere" is in fact a literal translation of the word "utopia".[8] This Utopia, an imagined society, is idyllic because the people in it are free from the burdens of industrialisation and therefore they find harmony in a lifestyle that coexists with the natural world. In an 1884 lecture "How We Live and How We Might Live", Morris gives his opinions about an ideal existence. This opinion is the bedrock for the novel. Morris writes, 'Before I leave this matter of the surroundings of life, I wish to meet a possible objection. I have spoken of machinery being used freely for releasing people from the more mechanical and repulsive part of necessary labour; it is the allowing of machines to be our masters and not our servants that so injures the beauty of life nowadays. And, again, that leads me to my last claim, which is that the material surroundings of my life should be pleasant, generous, and beautiful; that I know is a large claim, but this I will say about it, that if it cannot be satisfied, if every civilised community cannot provide such surroundings for all its members, I do not want the world to go on.'[9]

Influence

The title News from Nowhere has inspired many enterprises, including a political bookstore in Liverpool,[10] Tim Crouch's theatre company[11] and a monthly social club. The News from Nowhere Club was founded in 1996 to "challenge the commercialisation and isolation of modern life", taking as its motto Morris's phrase that "Fellowship is life and the lack of fellowship is death." Its patron is Peter Hennessy, historian of government, and it meets monthly in the church hall of St John The Baptist's, Leytonstone,[12] about four km from the house where the artist grew up, now the William Morris Gallery.

Many artistic creations are named News from Nowhere; some of these are closely connected to Morris's book, while others simply use the three-word title, or a variant of it. The Arts Council funded a short film in 1978, bringing News to Nowhere to life. It described a fictional trip by Morris up the River Thames, exploring ideas of aesthetic and socialism.[13] The book was adapted by Sarah Woods as a radio play, broadcast by BBC Radio 4 on 25 May 2016.

News From Nowhere was an influencing factor in historian G. D. H. Cole's conversion to socialism.[14] The novel News from Gardenia (2012) by Robert Llewellyn was influenced by News from Nowhere. A contemporary art exhibition at the Lucy Mackintosh Gallery in Lausanne, Switzerland, with six British artists: Michael Ashcroft, Juan Bolivar, Andrew Grassie, Justin Hibbs, Alistair Hudson, and Peter Liversidge during April–May 2005 was called News From Nowhere.[15] Korean artists Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonho were inspired by the novel in their collaborative project "News from Nowhere" (2012).[16]

Folk singer Leon Rosselson's song "Bringing the News from Nowhere", from his eponymous 1986 album, is a tribute to Morris. A track on Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!! by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds (2008) is called "More News from Nowhere". In 2013 the English band Darkstar released an album titled News from Nowhere. In 2008 Waltham Forest commissioned the composer, Mike Roberts, to create a new community symphony based on the story. Incorporating Morris' axiom of 'art for the people and by the people', the piece was written in collaboration with 180 primary school children, who composed fragments of music that were weaved into the final piece. The result was a 90-minute work for children's choir, orchestra and 10 other smaller ensembles. The work is being recorded with the artistic support of The William Morris Gallery during 2014-15 for release in June 2015 to commemorate the novel's 125th anniversary.

The animated video "News from Nowhere" (2022, 5 min) by Maltese artist and curator Raphael Vella is loosely inspired by William Morris’s novel. Composed of around 1000 frames, this stop motion animation presents a more dystopian version of the narrative, in which the artist wakes up to a world on fire. The animated video will be on display 2023 at Valletta Contemporary in Malta.[17]

See also

- Erewhon — 1872 utopian novel and satire on Victorian society by Samuel Butler

- Looking Backward — 1887 novel by Edward Bellamy in which the American protagonist falls asleep in 1887 and awakes in a socialist utopia in 2000

- List of books about anarchism

References

- Silver, Carole. The Romance of William Morris. Athens, Ohio: Ohio UP, 1982

- Michael Holzman (1984). "Anarchism and Utopia: William Morris's News from Nowhere". ELH. 51 (3): 589–603. doi:10.2307/2872939. JSTOR 2872939.

- Morris, William. "Bellamy's Looking Backward". The William Morris Internet Archive Works (1889). Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- Morris, W. (2003). News From Nowhere. Leopold, D (Ed.). New York, Oxford University Press Inc., New York.

- Levitas, Ruth. "Who Holds the Hose? Domestic Labor in the Work of Bellamy, Gillman, and Morris – Ebsco Host : Academic Search Premier 6 (1996)". Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- Morris, William (January 1994) [1890]. News from Nowhere and Other Writings. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-043330-9.

- Marsh, Jan. "Concerning Love: News From Nowhere and Gender." William Morris & News from Nowhere: A Vision for Our Time. Eds. Stephen Coleman and Paddy O'Sullivan. (Bideford, Devon: Green Books, 1990): 107–125

- Harper, Douglas. "utopia". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Salmon, Nicholas. "Works". Marxist Internet Archive. Retrieved 14 April 2008.

- News From Nowhere Co-operative Ltd. "News From Nowhere Radical & Community Bookshop, Liverpool". Newsfromnowhere.org.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- "Tim Crouch news from nowhere -news from nowhere". Newsfromnowhere.net. Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- "News From Nowhere Club". News From Nowhere Club. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- "News from Nowhere | review, synopsis, book tickets, showtimes, movie release date | Time Out London". Timeout.com. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- Cole, Margaret. The Life of G.D.H. Cole, p.33-4.

- "Galerie Lucy Mackintosh". Lucymackintosh.ch. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- "Home : News from nowhere". Newsfromnowhere.kr. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- "Raphael Vella - an interview by Maëla Sanmartín". inenart.eu. Retrieved 18 February 2023.