Áo ngũ thân

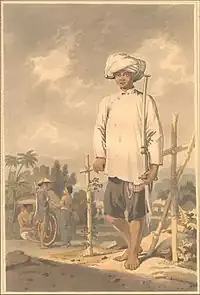

Áo ngũ thân lập lĩnh (Chữ Hán: 襖五身立領) or Áo năm thân (襖𠄼身) is the most popular costume in Vietnam under the Nguyễn dynasty, this costume was born in 1744, after the costume reform in Cochinchina by lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát.[1][2]

| Áo ngũ thân | |

Two girls wearing Áo ngũ thân in northern Vietnam, 1904 | |

| Vietnamese alphabet | áo ngũ thân áo năm thân |

|---|---|

| Chữ Hán | 襖五身 |

| Chữ Nôm | 襖𠄼身 |

Parts of dress

1. Body

Joined by five pieces of fabric (five parts): two front parts, two back parts, and a fifth part located in front, to the right of the wearer. Lapel flared and curved, not sewn straight. So when wearing it, the two sides are cupped, not revealing the hips, the waist is split like a modern áo dài.

2.Button

Áo ngũ thân has five buttons, the specific position is as shown in the photo. A common mistake is that the second button is often delayed. The second button and the first button in the middle of the neck must form a line perpendicular to the trung phùng line (the middle of the costume). Buttons are usually made from metal, wood, precious stones...

3.Clothes

Underneath Áo ngũ thân is a white dress.

4. Collar

The collar is square or rounded, hugging tightly to the neck. The inner collar is made of soft fabric, the outer collar is sewn to create a stand and hug. When worn, the inner collar is higher than áo ngũ thân collar.

5. Sleeves: 2 types (wide / tight)

No matter which sleeve style the shirt is sewn on, when it is spread flat on the sleeves, the shoulders should still be in a straight line.

- Sleeves are wide: sleeves must be equal to or longer than the length of the shirt (can be dotted to the ground or swept to the ground). Sleeves are always rectangular in shape, parallel to each other and not tied to the armpits, so when you fold your hands in front of your chest, you will have a square shape.

- This type is also known as Áo tấc, Áo thụng, Áo lễ, Áo rộng.

_postcard.jpg.webp)

- Sleeves are tight: from the armpit, the sleeves gradually narrow and hug the wrist.[3][4]

History

Nguyễn lords period

_(14745624366).jpg.webp)

In 1744,[5] lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát officially proclaimed himself vương and carried out a series of policies to present Đàng Trong as an independent country. History records that, when the lord ascended the throne, in Thuận Hóa spread the prophecy "Bát đại hoàn Trung đô", lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát wanted to change his destiny, so he decided to officially take the throne, for planning and building the Phú Xuân citadel ordered the renewal of customs and costumes throughout Cochinchina, including ceremonial and ordinary. With ceremonial vestments, the lord allowed "to consult the regime of Chinese dynasties, to make customary and dynastic clothes, to use them as a model, to promulgate in the country, to have all kinds of văn chất".

With the ordinary costume, the lord required that both men and women wear the collar Áo ngũ thân style, buttoned on the right side with two-leg pants, and put their hair in a bun on their heads. From here, the áo tứ thân, skirt, gradually ceased to appear popular in Cochinchina:

"Men, women and people[6] in the country all wear Áo nhu bào, wear pants, wear scarves, the custom of calling quần chân áo chít from here."

So the Áo ngũ thân was created by lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát, for both men and women, known as quần chân áo chít very quickly, it was quickly popularized throughout Cochinchina and only about 30 years later it became the main costume and characteristics of Cochinchina.[7]

Nguyễn dynasty

In 1822, Emperor Minh Mạng issued a decree to change clothes. The emperor forbade women not to wear quần không đáy (skirt) but to wear quần có đáy (pants).[8] In the 8th year of Minh Mạng (1827), the emperor decreed:

Our state and land are one, should politics and customs be different? Last month, the provincial officials in turn asked to change clothes for sĩ dân,[9] I allowed. Now, the regions in the Bắc thành should also promptly modify (clothes) to be uniform. But changing the customs is something that has just begun, and the poor and the rich are not equal, in terms of clothing needs, it takes a long time. So earnestly down this example: You guys should use your strength to inform sĩ dân in the regions: All clothes must be replaced to the clothes of the Southern of the country (from Quảng Bình onwards), the deadline is until the end of spring next year. The 10th Minh Mạng must definitely be revised to give the meaning of "vâng theo phép vua".

From this time on, Áo ngũ thân, standing collar, 5 buttons on the right side with two-leg pants was officially recognized as the national clothing of Vietnam, popular from the royal court to the folk. After Emperor Minh Mạng's regulations were announced to the entire people, causing the people to stir, they reacted with 6 ca daos:

- “Tháng tám có chiếu vua ra

- Cấm quần không đáy người ta hãi hùng

- Không đi thì chợ không đông

- Đi thì phải lột quần chồng sao đang!

- Có quần ra quán bán hàng

- Không quần ra đứng đầu làng trông quan."[10]

This incident shows that, every time, the improvement of costumes and fashion innovations, at first, have a certain force of support, but there will be many people who oppose and oppose. Therefore, the court's orders were not implemented thoroughly throughout the country, in the year of Đinh Dậu, the 18th year of Minh Mạng (1837), that is 10 years later, the emperor again issued an edict with a decisive attitude paralysis:

In the past, from Linh Giang back to the North, people still wore old clothes. Issued an edict to change according to southern clothes, so that the customs were uniform. Give a generous time limit, so that people can freely sew clothes and buy clothes. From the 8th year of Minh Mạng up to now, it has been ten years, still heard that the people have not changed (clothes). Besides, from Quảng Bình province to the southern provinces, hats, scarves, clothes are all in the style of the Han and Ming dynasties, looking quite neat. According to the old custom of the Northern people, men wear loincloths, women wear a costume with a tie the flap, and a skirt underneath. The beauty and the ugly were clearly seen. Some people have followed good customs, some people still keep their old habits, are they intentionally disobeying the above orders? Provincial mandarins should take that idea and instruct and advise the people. The deadline this year, must definitely change. If at the beginning of next year still keep the old clothes, it will be a crime.[11]

Modern

See also

Further reading

References

- Văn hóa dân gian. Viện văn hóa dân gian, Ủy ban khoa học xã hội Việt Nam. 2010. p. 53.

- Vu, Thuy (2014), "Đi tìm ngàn năm áo mũ", Tuổi Trẻ, retrieved June 16, 2015

- "Structural analysis of Áo ngũ thân lập lĩnh". Áo dài cô Sáu.

- "Áo dài ngũ thân cổ đứng khuy cài: Sự lịch duyệt đến từ chi tiết". VOV.

- "Áo dài Huế - Theo dòng lịch sử". Thuthienhue.gov.

- Sĩ thứ is used to refer to the people in ancient Vietnam, including sĩ phu (scholars) and thường dân (commoners)

- "Từ cải cách trang phục dưới thời Võ vương Nguyễn Phúc Khoát và vua Minh Mạng nghĩ đến tư tưởng thống nhất, tự chủ về văn hóa". Văn hóa Nghệ An.

- Mộc bản triều Nguyễn. 2009.

- educated people

- "Tháng tám có chiếu vua ra". Thi Viện.

- "Từ cải cách trang phục dưới thời Võ vương Nguyễn Phúc Khoát và vua Minh Mạng nghĩ đến tư tưởng thống nhất, tự chủ về văn hóa". Văn hóa Nghệ An.

_(14765465201).jpg.webp)