Niagara Falls, New York

Niagara Falls is a city in Niagara County, New York, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a total population of 48,671.[2] It is adjacent to the Niagara River, across from the city of Niagara Falls, Ontario, and named after the famed Niagara Falls which they share. The city is within the Buffalo–Niagara Falls metropolitan area and the Western New York region.

Niagara Falls | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Niagara Falls | |

The city of Niagara Falls. In the foreground are the waterfalls known as the American Falls and Bridal Veil Falls, respectively, from left to right. | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): Niagara Falls USA Honeymoon Capital of the World | |

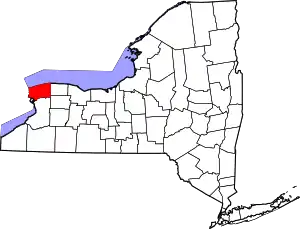

Location in Niagara County and the state of New York. | |

Niagara Falls Location in New York (state)  Niagara Falls Location within the United States | |

| Coordinates: 43°6′N 79°1′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Niagara |

| Settled | 1679 |

| Incorporated as a city | March 17, 1892 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong mayor-council |

| • Mayor | Robert Restaino (D) |

| • City Administrator | Anthony Restaino |

| • City Council | Members' List |

| Area | |

| • City | 16.83 sq mi (43.58 km2) |

| • Land | 14.09 sq mi (36.48 km2) |

| • Water | 2.74 sq mi (7.10 km2) 16.37% |

| • Urban | 366.7 sq mi (949.7 km2) |

| Elevation | 614 ft (187 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 48,671 |

| • Rank | NY: List of cities in New York (state) 34th (2010) |

| • Density | 3,455.27/sq mi (1,334.09/km2) |

| • Urban | 935,906 (US: 46th) |

| • Urban density | 2,663.5/sq mi (1,028.37/km2) |

| • Metro | 1,134,155 (US: 50th) |

| • CSA | 1,206,992 (US: 47th) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 14301-14305 |

| Area code | 716 |

| FIPS code | 36-51055 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0970406 |

| Demonym | Niagarian Niagara Fallsite |

| Website | niagarafallsusa |

While the city was formerly inhabited by Native Americans, Europeans who migrated to the Niagara Falls in the mid-17th century began to open businesses and develop infrastructure. Later in the 18th and 19th centuries, scientists and businessmen began harnessing the power of the Niagara River for electricity and the city began to attract manufacturers and other businesses drawn by the promise of inexpensive hydroelectric power. After the 1960s, however, the city and region witnessed an economic decline, following an attempt at urban renewal under then Mayor Lackey. Consistent with the rest of the Rust Belt as industries left the city, old line affluent families relocated to nearby suburbs and out of town.

Despite the decline in heavy industry, Niagara Falls State Park and the downtown area closest to the falls continue to thrive as a result of tourism. The population, however, has continued to decline from a peak of 102,394 in the 1960s due to the loss of manufacturing jobs in the area.

History

Before Europeans entered the area, it was dominated by the Neutral Nation of Native Americans. European migration into the area began in the 17th century. The first recorded European to visit the area was Frenchman Robert de la Salle, who built Fort Conti at the mouth of the Niagara River early in 1679, with permission from the Iroquois, as a base for boatbuilding; his ship Le Griffon was built on the upper Niagara River at or near Cayuga Creek in the same year.[3] He was accompanied by Belgian priest Louis Hennepin, who was the first known European to see the falls. The influx of newcomers may have been a catalyst for already hostile native tribes to turn to open warfare in competition for the fur trade.

The City of Niagara Falls was incorporated on March 17, 1892, from the villages of Manchester and Suspension Bridge, which were parts of the Town of Niagara. Thomas Vincent Welch, a member of the charter committee and a New York state assemblyman and a second-generation Irish American, persuaded Governor Roswell P. Flower to sign the bill on St. Patrick's Day. George W. Wright was elected the first mayor of Niagara Falls.[4]

By the end of the 19th century, the city was heavily industrialized, due in part to the power potential offered by the Niagara River. Tourism was considered a secondary niche, while manufacturing of petrochemicals, abrasives, metallurgical products and other materials was the main producer of jobs and attracted a large number of workers, many of whom were immigrants.

In 1927, the city annexed the village of La Salle, named for Robert de la Salle, from the Town of Niagara.

Industry and tourism grew steadily throughout the first half of the 20th century due to a high demand for industrial products and the increased mobility of people to travel. Paper, rubber, plastics, petrochemicals, carbon insulators and abrasives were among the city's major industries. This prosperity would end by the late 1960s as aging industrial plants moved to less expensive locations. In addition, the falls were incompatible with modern shipping technology.

In 1956, the Schoellkopf Power Plant on the lower river just downstream of the American Falls was critically damaged by the collapse of the Niagara Gorge wall above it. This prompted the planning and construction of one of the largest hydroelectric plants to be built in North America to that time, generating a large influx of workers and families to the area. New York City urban planner Robert Moses built the new power plant in nearby Lewiston, New York. Much of the power generated there fueled growing demands for power in downstate New York and New York City.

The neighborhood of Love Canal gained national media attention in 1978 when toxic waste contamination from a chemical landfill beneath it forced United States President Jimmy Carter to declare a state of emergency, the first such presidential declaration made for a non-natural disaster. Hundreds of residents were evacuated from the area, many of whom were ill because of exposure to chemical waste.[5]

After the Love Canal disaster, the city—which had already been declining in population for nearly two decades—experienced accelerated economic and political difficulties. The costs of manufacturing elsewhere had become less expensive, which led to the closure of several factories. The city's population eventually dropped by more than half of its peak, as workers fled the city in search of jobs elsewhere. Then, much like the nearby city of Buffalo, the city's economy plummeted when a failed urban renewal project destroyed Falls Street and the tourist district.

In 2001, the leadership of Laborers Local 91 was found guilty of extortion, racketeering and other crimes following an exposé by Mike Hudson of the Niagara Falls Reporter. Union boss Michael "Butch" Quarcini died before trial, while the rest of the union leadership was sentenced to prison.

In early 2010, former Niagara Falls Mayor Vincenzo Anello was indicted on federal charges of corruption, alleging the mayor accepted $40,000 in loans from a businessman who was later awarded a no-bid lease on city property. The charges were dropped as part of a plea deal after Anello pleaded guilty to unrelated charges of pension fraud, regarding a pension from the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, of which he is a member. He was sentenced to 10 to 16 months in prison.[6]

The city's decline received national exposure from Bloomberg Businessweek in 2010.[7]

On November 30, 2010, the New York State Attorney General entered into an agreement with the city and its police department to create new policies to govern police practices in response to claims of excessive force and police misconduct. The city committed to create policies and procedures to prevent and respond to allegations of excessive force, and to ensure police are properly trained and complaints are properly investigated. Prior claims filed by residents will be evaluated by an independent panel.[8]

In 2020, a public square named Cataract Commons opened on Old Falls Street. It is a public space for outdoor events and activities.[9][10]

The city has multiple properties on the National Register of Historic Places.[11] It also has three national historic districts, including Chilton Avenue-Orchard Parkway Historic District, Deveaux School Historic District and the Park Place Historic District.

Geography

Niagara Falls is at the international boundary between the United States and Canada. The city is within the Buffalo–Niagara Falls metropolitan area and is approximately 16 miles (26 km) from Buffalo, New York.[12]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 16.8 square miles (44 km2), of which 14.1 square miles (37 km2) is land and 2.8 square miles (7.3 km2) (16.37%) is water.[13] The city is built along the Niagara Falls and the Niagara Gorge, which is next to the Niagara River.

Climate

Niagara Falls has a humid continental climate (Dfa). The city experiences cold, snowy winters and hot, humid summers. Precipitation is moderate and consistent in all seasons, falling equally or more as snow during the winter. The city has snowier than average winters compared to most cities in the US, however less than many other cities in Upstate New York including nearby Buffalo and Rochester. Thaw cycles with temperatures above 32 °F (0 °C) are a common occurrence.[14] The hottest and coldest temperatures recorded in the decade through 2015 were 97 °F (36 °C) in 2005 and −13 °F (−25 °C) in 2003, respectively.[15] 38% of warm season precipitation falls in the form of a thunderstorm.[16]

| Climate data for Niagara Falls International Airport (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 65 (18) |

68 (20) |

81 (27) |

86 (30) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

97 (36) |

95 (35) |

96 (36) |

85 (29) |

80 (27) |

72 (22) |

97 (36) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 54.1 (12.3) |

51.1 (10.6) |

64.5 (18.1) |

78.9 (26.1) |

85.8 (29.9) |

88.8 (31.6) |

91.3 (32.9) |

89.1 (31.7) |

87.0 (30.6) |

78.2 (25.7) |

66.4 (19.1) |

56.2 (13.4) |

92.3 (33.5) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 31.5 (−0.3) |

32.7 (0.4) |

41.4 (5.2) |

54.5 (12.5) |

67.6 (19.8) |

76.3 (24.6) |

80.7 (27.1) |

79.1 (26.2) |

72.5 (22.5) |

59.5 (15.3) |

47.4 (8.6) |

36.7 (2.6) |

56.7 (13.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 24.2 (−4.3) |

25.0 (−3.9) |

33.0 (0.6) |

44.4 (6.9) |

56.6 (13.7) |

66.3 (19.1) |

71.0 (21.7) |

69.4 (20.8) |

62.3 (16.8) |

50.6 (10.3) |

39.7 (4.3) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

47.7 (8.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 16.8 (−8.4) |

17.3 (−8.2) |

24.7 (−4.1) |

34.3 (1.3) |

45.7 (7.6) |

56.2 (13.4) |

61.2 (16.2) |

59.6 (15.3) |

52.2 (11.2) |

41.6 (5.3) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

23.7 (−4.6) |

38.8 (3.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −1.3 (−18.5) |

−0.2 (−17.9) |

7.4 (−13.7) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

32.5 (0.3) |

44.6 (7.0) |

51.7 (10.9) |

50.2 (10.1) |

40.8 (4.9) |

28.7 (−1.8) |

18.9 (−7.3) |

8.4 (−13.1) |

−5.2 (−20.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −16 (−27) |

−13 (−25) |

−8 (−22) |

12 (−11) |

24 (−4) |

37 (3) |

46 (8) |

45 (7) |

30 (−1) |

23 (−5) |

−2 (−19) |

−4 (−20) |

−16 (−27) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.27 (58) |

1.77 (45) |

2.12 (54) |

3.19 (81) |

3.03 (77) |

2.88 (73) |

3.37 (86) |

2.62 (67) |

3.27 (83) |

3.23 (82) |

2.78 (71) |

2.44 (62) |

32.97 (837) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 15.0 | 12.5 | 12.1 | 13.4 | 12.8 | 11.6 | 11.5 | 10.5 | 10.8 | 15.3 | 12.6 | 15.5 | 153.6 |

| Source 1: NOAA[15] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[17] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Niagara Falls, New York (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1989–2019) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 65 (18) |

70 (21) |

81 (27) |

93 (34) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

97 (36) |

95 (35) |

93 (34) |

85 (29) |

72 (22) |

72 (22) |

97 (36) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 33.4 (0.8) |

34.5 (1.4) |

42.9 (6.1) |

55.8 (13.2) |

68.8 (20.4) |

77.6 (25.3) |

82.2 (27.9) |

80.4 (26.9) |

73.9 (23.3) |

61.2 (16.2) |

48.9 (9.4) |

38.5 (3.6) |

58.2 (14.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 26.0 (−3.3) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

34.4 (1.3) |

45.9 (7.7) |

58.3 (14.6) |

68.0 (20.0) |

72.8 (22.7) |

70.9 (21.6) |

63.7 (17.6) |

52.0 (11.1) |

41.2 (5.1) |

32.0 (0.0) |

49.3 (9.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 18.6 (−7.4) |

18.8 (−7.3) |

26.0 (−3.3) |

36.0 (2.2) |

47.9 (8.8) |

58.3 (14.6) |

63.4 (17.4) |

61.4 (16.3) |

53.6 (12.0) |

42.8 (6.0) |

33.4 (0.8) |

25.4 (−3.7) |

40.5 (4.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −15 (−26) |

−13 (−25) |

−9 (−23) |

14 (−10) |

28 (−2) |

38 (3) |

44 (7) |

44 (7) |

26 (−3) |

24 (−4) |

7 (−14) |

−7 (−22) |

−15 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.59 (66) |

2.10 (53) |

2.44 (62) |

3.10 (79) |

3.14 (80) |

2.99 (76) |

3.38 (86) |

2.80 (71) |

3.25 (83) |

3.27 (83) |

2.89 (73) |

2.76 (70) |

34.71 (882) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 22.3 (57) |

16.3 (41) |

11.6 (29) |

2.2 (5.6) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

4.1 (10) |

15.7 (40) |

72.4 (184) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 18.4 | 14.7 | 13.3 | 13.4 | 12.7 | 11.3 | 10.7 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 13.7 | 13.3 | 16.2 | 158.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 14.6 | 12.1 | 7.3 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 3.9 | 10.3 | 50.8 |

| Source: NOAA[15][18] | |||||||||||||

Neighborhoods

- Buffalo Avenue – runs along the south end along the Niagara River once home to a vast number of old families with architecturally significant mansions; further east (past John Daly Boulevard) the street is surrounded by a number of industrial sites to 56th Street before returning to a residential area and ending at the Love Canal area at 102nd Street.

- Central District[19]

- Deveaux – Located in the northwestern corner (west of the North End) along the Niagara River is residential area built in the 1920s to 1940s. Named for Judge Samuel DeVeaux who left his estate to be established as the Deveaux College for Orphans and Destitute Children in 1853 (closed 1971), now the site of DeVeaux Woods State Park[20] and DeVeaux School Historical District.

- Downtown – Area around the Falls and home to hotels including Seneca Niagara Resort Casino, Niagara Falls State Park, Niagara Falls Culinary Institute (formerly Rainbow Centre Factory Outlet)

- East Side – the area bounded by the gorge on the west, Niagara Street on the south, Ontario Avenue on the North and Main Street (NY Rt 104) on the east.[21]

- Hyde Park – Located near the namesake Hyde Park next to Little Italy as well as home to Hyde Park Municipal Golf Course.[22]

- LaSalle – Bounded by 80th Street, Niagara Falls Boulevard, Cayuga Drive and LaSalle Expressway was built up in the 1940s to 1960s. Cayuga Island is linked to neighborhood. The actual neighborhood where the Love Canal was to be built.[23]

- Little Italy – home to a once predominately Italian community that runs along Pine Avenue from Main Street to Hyde Park Boulevard

- Love Canal – Established in the 1950s on land acquired from Hooker Chemical Company. Most of the neighborhood was evacuated in the 1980s after toxic waste was discovered underground. Resettlement began in 1990.[24]

- Niagara Street – residential area east of Downtown along Niagara Street (distinct from Niagara Ave.) once home to a predominately German and Polish community.

- North End – runs along Highland Avenue in the north end of the city before it merges with Hyde Park Boulevard.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 3,006 | — | |

| 1880 | 3,320 | 10.4% | |

| 1890 | 5,502 | 65.7% | |

| 1900 | 19,457 | 253.6% | |

| 1910 | 30,445 | 56.5% | |

| 1920 | 50,760 | 66.7% | |

| 1930 | 74,460 | 46.7% | |

| 1940 | 78,020 | 4.8% | |

| 1950 | 90,872 | 16.5% | |

| 1960 | 102,394 | 12.7% | |

| 1970 | 85,615 | −16.4% | |

| 1980 | 71,384 | −16.6% | |

| 1990 | 61,840 | −13.4% | |

| 2000 | 55,593 | −10.1% | |

| 2010 | 50,193 | −9.7% | |

| 2020 | 48,671 | −3.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[25] | |||

As of the census of 2010, there were 50,193 people, 22,603 households, and 12,495 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,987.7 people per square mile (1,153.5 per square km). There were 26,220 housing units at an average density of 1,560.7 per square mile (602.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 70.5% White, 21.6% African American, 1.9% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 0% Pacific Islander, 0.8% from other races, and 3.9% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.0% of the population.

There were 22,603 households, out of which 23.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 29.8% were married couples living together, 19.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 44.7% were non-families. 38.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.20 and the average family size was 4.02.

In the city, 22% of the population was under the age of 18, 10.1% aged from 18 to 24, 24.2% from 25 to 44, 28.2% from 45 to 64, and 15.5% were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $26,800, and the median income for a family was $34,377. Males had a median income of $31,672 versus $22,124 for females. 23% of the population was below the poverty line.

Niagara Falls has a number of places of worship, including the Salvation Army, First Assembly of God Church, First Unitarian Universalist Church of Niagara, St. Peter's Episcopal Church, First Presbyterian Church, St. Theresa Roman Catholic Church in Deveaux, and the Reform Jewish Temple Beth El. The Conservative Jewish Temple Beth Israel closed in 2012.

Crime

Niagara Falls has struggled with high rates of violent and property crime; FBI crime data indicate that the city has among the highest crime rates in New York state.[26][27] In response to gun violence, volunteer groups such as Operation SNUG mobilized to promote positive community involvement in the troubled areas of the city.[28]

Economy

Niagara Falls' main industry is tourism, driven primarily by the waterfalls.[29]

A 2012 profile from the Office of the New York State Comptroller reported that Niagara Falls has "struggled through decades of population losses, rising crime and repeated attempts to reinvent itself from a manufacturing town with some tourism to a major tourist destination."[30] The city became a boomtown with the opening of the New York State Power Authority's hydroelectric Niagara Power Plant in the 1960s;[29] the cheap electricity produced by the plant generated power for a burgeoning manufacturing industry.[30] Along with the rest of Western New York, Niagara Falls suffered a significant economic decline from a decline in industry by the 1970s.[29] Today, the city struggles to compete with Niagara Falls, Ontario; the Canadian side has a greater average annual income, a higher average home price, and lower levels of vacant buildings and blight,[31] as well as a more vibrant economy and better tourism infrastructure.[32] The population of Niagara Falls, New York fell by half from the 1960s to 2012. In contrast, the population of Niagara Falls, Ontario more than tripled.[33] In 2000, the city's median household income was 36% below the national average.[29] In 2012, the city's unemployment rate was significantly higher than the statewide unemployment rate.[30]

Significant sources of economic activity in the region includes the Niagara Falls International Airport, which was renovated in 2009;[33] the Seneca Gaming Corporation's Seneca Niagara Casino & Hotel, which opened in the 2000s respectively;[33][29] and the nearby Niagara Falls Air Reserve Station.[29]

In late 2001, the State of New York established the USA Niagara Development Corporation, a subsidiary to the State's economic development agency, to focus specifically on facilitating development in the downtown area. However, the organization has been criticized for making little progress and doing little to improve the city's economy.[34]

Convention Center

%252C_New_York.jpg.webp)

From 1973 to 2002, the city had a Convention and Civic Center on 4th street. In 2002 the venue was converted into the Seneca Niagara Casino & Hotel. In 2004, a new Niagara Falls Convention Center (NFCC) opened on Old Falls Street. The Old Falls Street venue has 116,000 square feet for exhibitions and meetings, and a 32,200-square-foot event/exhibit hall.[35]

Tourism

The city is home to the Niagara Falls State Park. The park has several attractions, including Cave of the Winds behind the Bridal Veil Falls, Maid of the Mist, a popular boat tour which operates at the foot of the Rainbow Bridge, Prospect Point and its observation tower, Niagara Discovery Center, Niagara Falls Underground Railroad Heritage Center, and the Aquarium of Niagara.

Several other attractions also near the river, including Whirlpool State Park, De Veaux Woods State Park, Earl W. Brydges Artpark State Park in nearby Lewiston (town), New York, and Fort Niagara State Park in Youngstown, New York.

Attractions in the downtown include the Seneca Niagara Casino & Hotel and Pine Avenue which was historically home to a large Italian American population and is now known as Little Italy for its abundance of shops and quality restaurants.

Sports

The Niagara Power of the New York Collegiate Baseball League play at Sal Maglie Stadium. The team is owned by Niagara University. The Cataract City Wolverines of the Gridiron Developmental Football League are a minor league football team based in Niagara Falls. The team played their inaugural season in 2021.

In 2017, the Tier III junior North American 3 Hockey League team, the Lockport Express, relocated to Niagara Falls as the Niagara Falls PowerHawks.

Former sports teams based in Niagara Falls include the Class-A Niagara Falls Sox Minor League Baseball, the Class-A Niagara Falls Rapids and the Niagara Falls Lancers a Midwest Football League team were located within Niagara Falls.

Government

The City of Niagara Falls functions under a strong mayor-council form of government. The government consists of a mayor, a professional city administrator, and a city council. The current mayor is Robert Restaino.

The city council serves four-year, staggered terms, except in the case of a special election. It is headed by a chairperson, who votes in all items for council action.

On a state level, Niagara Falls is part of the 145th Assembly District of New York State, represented by Republican Angelo Morinello. Niagara Falls is also part of the 62nd Senate District of New York State, represented by Republican Robert Ortt.

On a national level, the city is part of New York's 26th congressional district and is represented by Congressman Brian Higgins. In the United States Senate, the city and the state are represented by senators Charles Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand.

Founded in 1892 Niagara Falls Police Department provide local law enforcement in the city with 155 sworn officers.[36] This force is not to be mistaken for the Town of Niagara, New York which has a smaller force founded in 1954.

Education

Residents are zoned to the Niagara Falls City School District. Niagara University and Niagara County Community College are the two colleges in Niagara County.

Media

Since Niagara Falls is within the Buffalo–Niagara Falls metropolitan area, the city's media is predominantly served by the city of Buffalo.

The city has two local newspapers, the Niagara Gazette, which is published daily except Tuesday and The Messenger Of Niagara Falls, NY which is published quarterly. The Messenger Of Niagara Falls, NY, which is officially Niagara Falls, New York's, first black-owned and operated news publication, founded October 2018. The Messenger Of Niagara Falls, NY published its inaugural issue April 2019. The Buffalo News is the closest major newspaper in the area. The city also is the home to a weekly tabloid known as the Niagara Falls Reporter.

Three radio stations are licensed to the city of Niagara Falls, including WHLD AM 1270, WEBR AM 1440, and WTOR AM 770.

Infrastructure

Niagara Falls is primarily served by the Buffalo Niagara International Airport for regional and domestic flights within the United States. The recently expanded Niagara Falls International Airport serves the city, and many cross border travellers with flights to Myrtle Beach, Fort Lauderdale, Orlando and Punta Gorda. Toronto's Pearson International Airport on the Canadian side is the closest airport offering long-haul international flights for the Niagara region.

The city is served by Amtrak's Maple Leaf and Empire train services, with regular stops at the Niagara Falls Station and Customhouse Interpretive Center at 825 Depot Ave West.

Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority is the public transit provider in the Buffalo metro area, with hubs at the Portage Road and Niagara Falls transportation centers.

Six New York State highways, one three-digit Interstate Highway, one expressway, one U.S. Highway, and one parkways pass through the city of Niagara Falls. New York State Route 31, New York State Route 104, and New York State Route 182 are east–west state roadways within the city, while New York State Route 61, New York State Route 265, and New York State Route 384 are north–south state roadways within the city. The LaSalle Expressway is an east–west highway which terminates near the eastern edge of Niagara Falls and begins in the nearby town of Wheatfield, New York. The Niagara Scenic Parkway is a north–south parkway that formerly ran through the city along the northern edge of the Niagara River. It remains in sections and terminates in Youngstown, New York.

Interstate 190, also referred to as the Niagara Expressway, is a north–south highway and a spur of Interstate 90 which borders the eastern end of the city. The highway enters the city from the town of Niagara and exits at the North Grand Island Bridge. U.S. Route 62, known as Niagara Falls Boulevard, Walnut Avenue, and Ferry Avenue, is signed as a north–south highway. U.S. Route 62 has an east–west orientation, and is partially split between two one-way streets within Niagara Falls. Walnut Avenue carries U.S. Route 62 west to its northern terminus at NY 104, and Ferry Avenue carries U.S. Route 62 east from downtown Niagara Falls. U.S. Route 62 Business, locally known as Pine Avenue, is an east–west route which parallels U.S. Route 62 to the south. Its western terminus is at NY 104, and its eastern terminus is at U.S. Route 62.

Two international bridges connect the city to Niagara Falls, Ontario. The Rainbow Bridge connects the two cities with passenger and pedestrian traffic and overlooks the Niagara Falls, while the Whirlpool Rapids Bridge, which formerly carried the Canadian National Railway, now serves local traffic and Amtrak's Maple Leaf service.

Notable people

See also

References

- "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- "Census - Geography Profile: Niagara Falls city, Niagara County, New York". Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- "Old Fort Niagara". www.oldfortniagara.org. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- "Niagara Falls New York Township History - The City of Niagara Falls, New York, USA". Niagarafallsinfo.com. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- "Love Canal Collection". University of Buffalo Libraries. Archived from the original on September 23, 2011. Retrieved February 3, 2007.

- Pfeiffer, Rick (September 2, 2010). "Prison for former Falls mayor Vince Anello". Niagara Gazette. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- "The Fall of Niagara Falls". Bloomberg Business. December 2, 2010. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- New York State Office of the Attorney General (November 30, 2010). "Attorney General Cuomo Reaches Agreement With The City Of Niagara Falls To Reform Its Police Practices". Ag.ny.gov. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- "USA Niagara Breaks Ground on Cataract Commons Project in Niagara Falls". Empire State Development. State of New York. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- Anstey, Evan (July 17, 2020). "Cataract Commons opens in Niagara Falls". WIVB. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- "Distance between Buffalo, NY and Niagara Falls, NY". www.distance-cities.com. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- United States Census Bureau (2010). "American FactFinder - Geographic Identifiers, Niagara Falls city, New York". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Niagara Falls INTL AP, NY". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- "Weather Spark Niagara". Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Buffalo". National Weather Service. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- "Station: Niagara Falls, NY". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- see map for boundaries the area corresponding to a region with boundaries around the text City of Niagara Falls

- "Niagara County Historical Society's Bicentennial Moments – DeVeaux School". Niagara2008.com. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- "East Side, Niagara Falls, NY Real Estate Market". www.realtor.com.

- "Niagara Falls City Government HydePark". Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved April 19, 2016.

- "La Salle 14304 Niagara Falls, NY Neighborhood Profile". Neighborhoodscout.com. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- "Love Canal". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- United States Census Bureau. "Niagara Falls city, New York". Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- Evan Anstey (August 29, 2019). "Niagara Falls comes in last on list of safest cities in NY". WIVB-TV.

- Kaley Lynch (July 7, 2017). "Niagara Falls, Buffalo ranked as #1, #3 most dangerous places to live in Upstate New York". WIVB-TV.

- Nalina Shapiro (April 17, 2011). "Residents on mission to stop violence". WIVB-TV. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- David Staba (May 30, 2005). "Niagara Falls, Already in Decline, Faces Another Blow". New York Times.

- 2012 Fiscal Profiles: City of Niagara Falls (PDF) (Report). Office of the New York State Comptroller. December 2012.

- Brady, Jonann (September 16, 2008). "Niagara Falls: A Tale of Two Cities". Good Morning America. ABC News.

- Nick Mattera (February 5, 2011). "A tale of two cities". Niagara Gazette.

- Mark Byrnes (June 14, 2012). "Can Niagara Falls Grow Again?". The Atlantic/CityLab.

- Mark Scheer (February 1, 2009). "USA NIAGARA: The "Times Square" promise". Niagara Gazette.

- "Niagara Falls Conference Center". Empire State Development. State of New York. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- "Niagara Falls Police Department – Niagara Falls".

Further reading

- Mah, Alice. Industrial Ruination, Community, and Place: Landscapes and Legacies of Urban Decline (University of Toronto Press; 2012) 240 pages; comparative study of urban and industrial decline in Niagara Falls (Canada and the United States), Newcastle upon Tyne, Britain, and Ivanovo, Russia.

External links

- Official website

- Niagara Falls Handbill Collection, 1838-1886 RG 551 Brock University Library Digital Repository

- Niagara Falls Photo Album, 1906 RG 556 Brock University Library Digital Repository