Nickel Plate Glass Company

The Nickel Plate Glass Company was a manufacturer of tableware, lamps, and bar goods. It began operations in Fostoria, Ohio, on August 8, 1888, on land donated by the townspeople. The new company was formed by men from West Virginia who were experienced in the glassmaking business, and their company was incorporated in that state in February of the same year. They were lured to northwest Ohio to take advantage of newly discovered natural gas that was an ideal low-cost fuel for glassmaking. The company name came from the New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad, commonly known as the "Nickel Plate Road", which had tracks adjacent to the new glass plant.

| Type | Private company |

|---|---|

| Industry | Glassware |

| Founded | 1888 |

| Founder | Andrew J. Smith, Benjamin M. Hildreth, Peter Cassell, August Rolf, James B. Russell |

| Defunct | 1891 |

| Successor | Factory N of U.S. Glass Company |

| Headquarters | Fostoria, Ohio, U.S. |

Key people | Andrew J. Smith, James B. Russell, Charles Foster |

| Products | |

Number of employees | 350 (January 1891) |

Northwest Ohio had a short "gas boom", starting in 1886 after the Karg Well was drilled near Findlay, Ohio. Local businessmen took advantage of the natural gas to lure new businesses to the town. Numerous businesses were started in the area, and collectively they depleted the natural gas supply by the early 1890s. On July 1, 1891, Nickel Plate Glass Company joined the United States Glass Company trust, becoming Factory N. The trust controlled more than a dozen glass plants that made tableware. Initially the trust did not get involved with Factory N's operations. An economic depression, also known as the Panic of 1893, began in January 1893. On August 12, 1893, the trust closed Factory N permanently. After attempts to restart the plant failed, the facility burned to the ground on August 28, 1895.

The glass works operated for nearly three years as the Nickel Plate Glass Company, and about two more years as Factory N of the United States Glass Company. It is remembered as one of 13 glass companies that produced in Fostoria between 1887 through 1920. Today, collectors value patterns made by Nickel Plate/Factory N now called 101 Pattern Glass, Columbian Coin, Double Greek Key, Frosted Circle, Richmond, and others. The company also made unique lamps that featured a patented double–screw that connected the base of the lamp to the lamp fount that held the kerosine.

Background

In the last half of the 19th century, labor and fuel were the two largest expenses in U.S. glassmaking.[1] People with the knowledge necessary to make glass were difficult to find. Management at Wheeling's J. H. Hobbs, Brockunier and Company had a policy of using skilled glassworkers from Europe, who would train the local employees—resulting in a superior workforce.[2][Note 1] Former employees of the Wheeling glass works became the talent that helped establish many of the region's glass factories, and many became company presidents or plant managers.[2]

Since fuel was one of the top two expenses in glassmaking, manufacturers needed to monitor its availability and cost.[1] Wood and coal had long been used as fuel for glassmaking. An alternative fuel, natural gas, became a desirable fuel for making glass because it is clean, gives a uniform heat, is easier to control, and melts the batch of ingredients faster. Gas furnaces for making glass were first used in Europe in 1861.[6] In early 1886, a major discovery of natural gas (the Karg Well) occurred in northwest Ohio near the small village of Findlay.[7] Communities in northwestern Ohio began using low-cost natural gas along with free land and cash to entice glass companies to start operations in their town.[8] Their efforts were successful, and at least 70 glass factories existed in northwest Ohio between 1886 and the early 20th century.[9] The city of Fostoria, already blessed with multiple railroad lines, was close enough to the natural gas that it used a pipeline to make natural gas available to businesses.[10]

Early years

Beginning

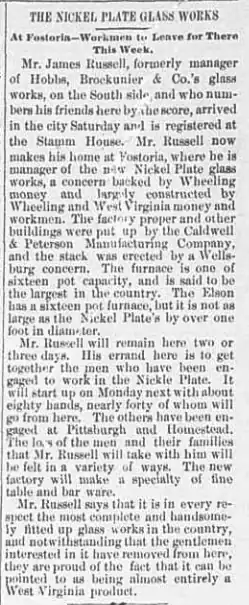

The Nickel Plate Glass Company was formed in West Virginia in early 1888 by a group of glass men from Wheeling, West Virginia, and points nearby. The major shareholders were Peter Cassell, August Rolf, Andy J. Smith, Benjamin Hildreth, W. H. Robinson, and James B. Russell.[11] Smith, who previously worked at Elson Glass Company in Martins Ferry, Ohio, was the president and general manager. Hildreth was secretary and treasurer, and Russell was plant manager.[12] Hildreth and Russell had worked at Hobbs, Brockunier and Company and Fostoria Glass Company.[13] The company was named Nickel Plate Glass Company because the railroad adjacent to the factory grounds was commonly known as the "Nickel Plate Road" despite its real name of New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad.[14][Note 2]

The founders were enticed to build their glass factory in Fostoria, Ohio. They were guaranteed $8,000 (equivalent to $260,563 in 2022) cash, five acres (2.0 ha) of land, no taxes, and free natural gas forever.[17][Note 3] The men making the guarantees were prominent local capitalists Charles Foster, Rawson Crocker, and Edward Marks.[11] Foster was the son of the city of Fostoria's namesake, and had been governor of Ohio. He was involved in banking, natural gas, many of Fostoria's glass factories, and other industrial companies. Later in 1891, he became U.S. Treasury Secretary under President Benjamin Harrison.[18] The new glass factory to be constructed would have a 16-pot furnace, which would be one of the larger furnaces in the United States.[19][Note 4] The new plant would start with about 80 workers, and about half came from the Wheeling area.[19]

Operations

By July the factory was completed and the 16-pot furnace was operating.[21] Production began on August 8, and advertisements later in the year mentioned lamps, tableware, blown tumblers, and bar goods. The company also had a line of tableware and lamps in crystal and opalescent glass.[22][Note 5] Pressed glass in patterns was their principal product.[24] A trade magazine article dated January 24, 1889, stated that the glass works was so busy that it had operated every day except Christmas Day since operations began.[25][Note 6]

Production continued into June with expectations it would continue until the summer break and restart in early autumn.[27] The factory remained busy over the next few years and introduced more glassware patterns, but had occasional stoppages caused by shortages of natural gas.[28] Issues with natural gas became more common in northwest Ohio during this time. During the winters of 1888 and 1889, gas usage had to be curtailed and sometimes shut off completely.[9][Note 7] Despite the natural gas problem, Nickel Plate Glass Company grew to 350 workers by January 1891.[29]

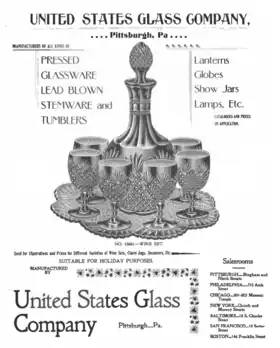

U.S. Glass

In February 1891, a glass trust named United States Glass Company was formed in Pennsylvania.[30] A.J. Smith, of Fostoria, was listed as one of the directors of the new company.[31] The trust was headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and it originally consisted of 13 glass companies. Its stated objective was "to systematize and harmonize the workings of the several plants and secure such economies in cost as may result from a consolidation of interests."[32] Initially, it was assumed that the trust planned to control the tableware market and raise prices.[33] However, some publicity surrounding the trust implied that it was created for lowering prices, not raising them.[34]

The United States was in an economic recession at the time of the formation of the glass trust, although the economy started improving after May.[35] Two ways to make the plants produce products at lower prices were to get concessions from the unions and to introduce more machines.[36] It is the opinion of some experts that the U.S. Glass trust was formed to "oppose the union and to introduce the automated equipment."[37] The American Flint Glass Workers' Union was naturally opposed to mechanization or concessions, and the union was strong enough that a single glass works could not oppose it.[37] U.S. Glass eventually built large new glass works at Gas City, Indiana, and Glassport, Pennsylvania. The new plants were highly automated—and could be used to oppose unions at the other plants.[37]

The Nickel Plate Glass Company was listed as one of the incorporators of the new company, and officially joined the trust on July 1, 1891, when the Fostoria company ceased to exist as a corporate entity.[38] Each factory that was part of the trust became known by a letter (e.g. Factory A of United States Glass Company).[39] The Nickel Plate Glass Company became Factory N, although the locals still called it the "Nickel Plate".[40] The companies combined into the trust were from Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, and the count of firms quickly grew larger.[41] Some firms that joined the trust, such as Fostoria's Novelty Glass Company, were in financial difficulty.[42] That was not the case for the Nickel Plate Glass Company, as the company was described in August 1891 as being so successful during its three years of existence that it could use its earnings to double its capital.[43] Another glass company from the town, Fostoria Glass Company, left to re-establish itself in Moundsville, West Virginia—solving its natural gas fuel problem with the abundant coal near the town in Marshall County.[44] The changes at Factory N were few, and the plant appeared to operate without much interference from trust management.[45] Smith, Hildreth, and Russell still ran the plant. Only Smith's title changed: from president to superintendent.[46]

Patterns

Nickel Plate

Some of the glassware advertised by the Nickel Plate Glass Company had a swirl design (collectors call it Nickel Plate Swirl). The glass was often colored, with the cap of the swirls having a soft white opalescence.[47][Note 8] During January 1889, a glassware magazine commented on a new glassware pattern introduced by the Nickel Plate Glass Company. The pattern was called Grecian key (collectors call it Double Greek Key), and the magazine said it was "very handsome...and will prove popular".[48][Note 9] In September 1889 a new pattern began being promoted. This pattern, number 76, was called Richmond, and it became one of the company's most popular patterns.[49][Note 10] An article from April 1891 discussed pattern number 101, which appears like a one followed by zero followed by a one—although the zeros are more prominent than the ones. Also introduced was a patented double-screw that connected the lamp's stand with the fount that contained the lamp's kerosine fuel.[52][Note 11]

Factory N

The Nickel Plate plant's product line was changed only slightly when it became "Factory N, and it continued to make popular patterns.[54] Two new patterns introduced in 1892 are now called by collectors Frosted Circle and Columbian Coin.[55] Frosted Circle was pattern number 15007, and it featured a circle on the glassware that appeared frosted because of etching. The same pattern with the circle was also issued without the etching (frosting).[56][Note 12] In early 1892, factories that were part of United States Glass Company (Factory O and Factory H) began making coin pattern glass.[59][Note 13] The pattern looked like a United States coin embedded in the glassware. After about five months of production, the federal government declared the coin pattern glass illegal, and the two glass works were forced to destroy their molds. A way to circumvent the legal issue was to produce a glass coin that was not a replica of United States currency—and other glass factories did that by making a pattern called Columbian Coin.[59] In September 1892, Factory N produced one of the most famous glass patterns in America at the time: pattern number 15005 1/2—which replaced the coin pattern (number 15005) made by Factories O and H.[61][Note 14] This Columbian Coin pattern was used for the Chicago World's Fair. Among novelties made was a coin with the likeness of Christopher Columbus on one side and Amerigo Vespucci on the other. Other products were Masonic items with an emphasis of Chicago's Masonic Temple.[61]

Decline

In September 1892, U.S. Glass Company completed negotiations to build a works in Gas City, Indiana, that would have three 15-pot furnaces. The highly automated plant was expected to be ready in the spring (1893) and make use of the town's abundant natural gas supply.[63] Smith resigned as leader of Factory N in November 1892. He moved to Kent, Ohio, to operate the Edward Dithridge Company glass plant.[64][Note 15] The trust decided to remedy Factory N's natural gas shortage problem in January 1893 by switching to an oil-based fuel.[66]

Although the fuel problem was fixed, economic trouble became Factory N's next issue. An economic depression, which actually began in January 1893 and became known as the Panic of 1893, brought deflation and a high unemployment to the nation.[67] United States Glass Company announced in August that 13 of its factories (including Factory N) would shutdown permanently effective August 12.[68] U.S. Glass and its unionized workers had their differences, but large automated non-union plants, such as the Gas City plant, could be used by the trust to produce glassware without the unionized factories.[37] There were some efforts by the local workers to revive the closed glass works during the next few years, but this ended in 1895 when the factory burned to the ground.[69]

Notes

Footnotes

- The J.H. Hobbs, Brockunier and Company was reorganized multiple times over a period of about 50 years. It began as Barnes, Hobbs and Company in 1845. It was later named Hobbs, Barnes, and Company and also Hobbs and Barnes. After Barnes retired in 1863, the company was reorganized as J.H. Hobbs, Brockunier and Company.[3] This version lasted until 1881, when John L. Hobbs died and the company reorganized as Hobbs, Brockunier and Company.[4] A new version of the company, a corporation instead of a partnership, was organized in 1888 as the Hobbs Glass Company.[5]

- Nickel Plate Glass Company spelled the name with a hyphen (Nickel–Plate Glass Co.) in advertisements in the glass journals Pottery and Glassware Reporter and China, Glass and Lamps.[15] The State of West Virginia, in its Acts of the Legislature published in 1889, spells the name without a hyphen when discussing the 1888 act of incorporation.[16]

- Murray states that that the enticement information came from the Crockery & Glass Journal, March 1, 1888 edition.[17] Paquette also mentions the $8,000 gift and states that it was unusual for the details to be released to the public.[11]

- Because most glass plants melted their ingredients in a pot, the plant's number of pots was often used to describe a plant's capacity. The ceramic pots were located inside the furnace. The pot contained molten glass created by melting a batch of ingredients that typically included sand, soda, lime, and other ingredients.[20]

- Murray shows a picture of the 1891 Nickel Plate Glass Company letterhead, which mentions table ware, lamps, and bar goods. He also shows an advertisement by the Nickel Plate Glass Company in the Pottery and Glassware Reporter dated November 29, 1888.[23]

- Murray cites an article dated January 24, 1889, by the Pottery and Glassware Reporter that discusses "how busy the plant has been" since it began.[26]

- Ohio's natural gas shortages eventually caused many glass companies to close, switch fuel, or move elsewhere.[9]

- Murray shows advertisements with Nickel Plate Glass Company glassware with swirls. The advertisements are from the November 29, 1888, and January 16, 1890, issues of Pottery and Glassware Reporter.[23]

- Murray cites an article dated January 24, 1889, by the Pottery and Glassware Reporter for the mention of Grecian key.[26]

- Murray cites the September 26, 1889, issue of Crockery & Glass Journal for the information on the Richmond pattern.[50] He also shows a page from the company's catalog that shows some items said to be in the Richmond pattern.[51]

- Murray cites the April 22, 1891, issue of China, Glass & Lamps for the information on the 101 pattern and the double screw.[53] He also shows a page from the company's catalog that has a lamp (stand or base, double-screw, fount, and chimney with shade) with the 101 pattern on the base.[17]

- Murray cites an article dated May 12, 1892, by the Crockery & Glass Journal.[57] He also shows a catalog page that displays the Frosted Circle pattern.[58]

- The former Central Glass Company was known as Factory O, and the former Hobbs Glass Company was known as Factory H.[60]

- Murray cites an article dated September 1, 1892, by the Crockery & Glass Journal for a discussion of the World's Fair pattern and products.[62]

- Murray cites an article dated November 24, 1892, by the Crockery & Glass Journal that discusses Smith leaving Plant N for the Edward Dithridge Company.[65]

Citations

- United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 12

- "South Wheeling Glass Works (page 3 far left column)". Wheeling daily Intelligencer (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). December 12, 1873. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 9, 2023.

- Baker 1986, p. 108

- "The Glass Houses (columns on left side of p.9)". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). September 14, 1886. Archived from the original on July 14, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 21

- United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 36

- Paquette 2002, pp. 24–25

- Paquette 2002, p. 26

- Paquette 2002, p. 28

- H. Sabine, Commissioner of Rail Roads & Telegraphs (1882). New Rail Road Map of Ohio prepared by H. Sabine, Commissioner of Rail Roads & Telegraphs (Map). Wapakoneta, Ohio: R. Sutton (Library of Congress). Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved August 5, 2023.; Paquette 2002, p. 173; Geological Survey of Ohio 1890, p. 190

- Paquette 2002, p. 189

- Paquette 2002, p. 189; Welker & Welker 1985, p. 79

- Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 29; Paquette 2002, p. 189

- Paquette 2002, p. 189; "Nickel Plate Road – Transporting the Economic Might of the Midwest". Nickel Plate Road Historical & Technical Society. Archived from the original on August 5, 2023. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- Murray 1992, pp. 104, 108–109

- West Virginia 1889, p. 407

- Murray 1992, p. 105

- Paquette 2002, pp. 174–175; "Gov. Charles Foster". National Governors Association. Archived from the original on March 24, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.; "Ohio Historical Marker: Fostoria, Ohio – Home of Fostoria Glass". Destination Seneca County. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- "The Nickel Plate Glass Works". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. August 8, 1888. Archived from the original on August 6, 2023. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- Skrabec 2007, pp. 25–26

- "(Untitled near top of page 6) The Nickel Plate Glass Company..." Wheeling Sunday Register. July 6, 1888. Archived from the original on August 6, 2023. Retrieved August 6, 2023.; Geological Survey of Ohio 1890, p. 191

- Paquette 2002, p. 190; "The Nickel Plate Glass Works". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. August 8, 1888. Archived from the original on August 6, 2023. Retrieved August 6, 2023.; Welker & Welker 1985, p. 79; Murray 1992, p. 104

- Murray 1992, p. 104

- Welker & Welker 1985, p. 79

- Murray 1992, pp. 105–106; Paquette 2002, p. 190

- Murray 1992, pp. 105–106

- "(Untitled near bottom of page 4, second column from left) Andy J. Smith, of the Nickel Plate..." Wheeling Sunday Register. June 19, 1889. Archived from the original on August 6, 2023. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- Paquette 2002, p. 190

- "Glassware Men Combine". Janesville Daily Gazette. January 8, 1891. p. 2.

Nineteen Factories in Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia Join Hands

- Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 22; Paquette 2002, p. 191

- "Three Charters Granted (page 2 near center)". Pittsburg Dispatch (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). February 13, 1891. Archived from the original on 2023-08-12. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- "Table Glassware Works Combine (page 4 col. 5 from right)". Wheeling Daily Register (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). July 16, 1891. Archived from the original on 2023-08-12. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- "The Tableware Trust (page 1 2nd col. from right)". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). February 21, 1891. Archived from the original on 2023-08-07. Retrieved 2023-08-07.

- "A Glass Trust (page 2 top of page near middle)". Ocala Banner (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). July 31, 1891. Archived from the original on 2023-08-07. Retrieved 2023-08-07.

- "US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions". National Bureau of Economic Research. Archived from the original on December 1, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 23

- Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 24

- Paquette 2002, p. 191

- Lechner & Lechner 1998, p. 158

- Paquette 2002, p. 210; Skrabec 2007a, p. 55

- Skrabec 2007a, p. 55

- Murray 1992, p. 109; Paquette 2002, p. 206

- "Sherman's anti-Trust Law". Petersburg Pike County Democrat. August 19, 1891. p. 4.

One of the members of this trust, the Nickel Plate Glass Co., started three years ago, was so successful that it was able to double its capital out of its earnings...

- Paquette 2002, pp. 181–183

- Welker & Welker 1985, p. 79; Paquette 2002, pp. 210–211

- Paquette 2002, pp. 210–211; Lechner & Lechner 1998, p. 136

- Murray 1992, p. 104; "NICKEL PLATE SWIRL (AKA)". Early American Pattern Glass Society. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2023.;

- Murray 1992, p. 106; Lechner & Lechner 1998, p. 158; "DOUBLE GREEK KEY (AKA) (Nickel Plate Glass Company)". Early American Pattern Glass Society. Archived from the original on November 27, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- Murray 1992, pp. 106, 116; "NICKEL PLATE GLASS CO. No. .76 RICHMOND (OMN) line". Early American Pattern Glass Society. Archived from the original on August 5, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- Murray 1992, p. 106

- Murray 1992, p. 116

- Murray 1992, pp. 105, 107–108; "NICKEL PLATE GLASS CO. No. 101 (OMN)". Early American Pattern Glass Society. Archived from the original on August 14, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- Murray 1992, pp. 107–108

- Paquette 2002, pp. 210–211

- Murray 1992, pp. 109–110; "UNITED STATES GLASS CO. No. 15005-1/2 WORLD'S FAIR (OMN)". Early American Pattern Glass Society. Archived from the original on September 30, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2023.; "UNITED STATES GLASS CO. No. 15007 (OMN)". Early American Pattern Glass Society. Archived from the original on August 15, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- Murray 1992, pp. 108–109; "UNITED STATES GLASS CO. No. 15007 (OMN)". Early American Pattern Glass Society. Archived from the original on August 15, 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- Murray 1992, p. 109

- Murray 1992, p. 108

- Shotwell 2002, p. 95

- Shotwell 2002, pp. 80, 244

- Murray 1992, pp. 109–110; "UNITED STATES GLASS CO. No. 15005-1/2 WORLD'S FAIR (OMN)". Early American Pattern Glass Society. Archived from the original on September 30, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- Murray 1992, pp. 109–110

- "A New Interest Added (page 3 near bottom)". Pittsburgh Dispatch (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). September 4, 1892. Archived from the original on 2023-08-12. Retrieved 2023-08-12.; Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 24

- Paquette 2002, p. 211; Murray 1992, pp. 110–11

- Murray 1992, pp. 110–111

- Paquette 2002, p. 211

- "The Depression of 1893". Economic History Association. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- Paquette 2002, pp. 211–212

- Welker & Welker 1985, p. 79; Paquette 2002, pp. 212–213

References

- Baker, Gary E. (June 1986). The Flint Glass Industry in Wheeling, West Virginia: 1829–1865 (MA). University of Delaware. Archived from the original on 2023-07-12. Retrieved 2023-07-12.

- Bredehoft, Neila M.; Bredehoft, Thomas H. (1997). Hobbs, Brockunier and Co., Glass: Identification and Value Guide. Paducah, KY: Collector Books. ISBN 978-0-89145-780-0. OCLC 37340501.

- Geological Survey of Ohio (1890). Annual Report of the Geological Survey of Ohio. Columbus, Ohio: Westbote Co., State Printers. OCLC 13585464. Archived from the original on August 3, 2023. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- Lechner, Mildred; Lechner, Ralph (1998). The World of Salt Shakers: Antique & Art Glass Value Guide Volume III. Paducah, Kentucky: Collector Books. ISBN 978-1-57432-065-7. OCLC 39502285.

- Murray, Melvin L. (1992). Fostoria, Ohio Glass II. Fostoria, OH: M. L. Murray. OCLC 27036061.

- Paquette, Jack K. (2002). Blowpipes, Northwest Ohio Glassmaking in the Gas Boom of the 1880s. Xlibris Corp. ISBN 1-4010-4790-4. OCLC 50932436.

- Shotwell, David J. (2002). Glass A to Z. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. ISBN 978-0-87349-385-7. OCLC 440702171.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2007). Michael Owens and the Glass Industry. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing. OCLC 137341537.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2007a). Glass in Northwest Ohio. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-73855-111-1. OCLC 124093123.

- United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce (1917). The Glass Industry. Report on the Cost of Production of Glass in the United States. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 5705310.

- Welker, John; Welker, Elizabeth (1985). Pressed Glass in America: Encyclopedia of the First Hundred Years, 1825–1925. Ivyland, Pennsylvania: Antique Acres Press. ISBN 978-0-96158-610-2. OCLC 12909662.

- West Virginia (1889). Acts of the Legislature of West Virginia. Charleston, West Virginia: Moses W. Donnally, Public Printer. OCLC 1769663. Archived from the original on 2023-08-16. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

Nickel Plate Glass Company

External links

- Nickel Plate Glass page – Fostoria Ohio Glass Association

- Nickel Plate various patterns – Early American Pattern Glass Society